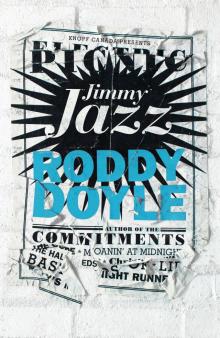

Jimmy Jazz

Roddy Doyle

ALSO BY RODDY DOYLE

Fiction

The Commitments

The Snapper

The Van

Paddy Clarke Ha Ha Ha

The Woman Who Walked Into Doors

A Star Called Henry

Oh, Play That Thing

Paula Spencer

The Deportees

The Dead Republic

Bullfighting

Two Pints

Non-Fiction

Rory & Ita

Plays

Brownbread

War

Guess Who’s Coming for the Dinner

The Woman Who Walked Into Doors

The Government Inspector (translation)

For Children

The Giggler Treatment

Rover Saves Christmas

The Meanwhile Adventures

Wilderness

Her Mother’s Face

A Greyhound of a Girl

ABOUT THE BOOK

Jimmy Rabbitte hates jazz, always has. But his wife Aiofe loves it, and Jimmy loves Aiofe. So when, in attempt to convert him, she buys him two tickets for a Keith Jarrett concert he decides to take Outspan, former member of Jimmy’s band The Commitments, who has come back into his life after a chance meeting in the cancer clinic. Jarrett is famous for being intolerant of any noise at all – a cough, a sneeze, a wheeze – from the audience, stopping playing and shaming the perpetrator. And Outspan’s diagnosis is lung cancer, it’s pretty bad, and he needs an oxygen cylinder to breathe properly.

Will Outspan create havoc? Will Jimmy learn to love jazz at last?

JIMMY JAZZ

Roddy Doyle

PUBLISHED BY ALFRED A. KNOPF CANADA

Copyright © 2013 Roddy Doyle

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer, who may quote brief passages in a review. Published in 2013 by Alfred A. Knopf Canada, a division of Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto, and simultaneously in the United Kingdom by Jonathan Cape, a division of The Random House Publishing Group, a division of Random House Inc., London. Distributed in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited.

www.randomhouse.ca

Knopf Canada and colophon are registered trademarks.

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or locales is entirely coincidental.

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Doyle, Roddy, 1958–, author

Jimmy jazz : a Jimmy Rabbitte story / Roddy Doyle.

Electronic monograph in HTML format.

ISBN 978-0-345-80892-9

I. Title.

PR6054.O95J56 2013 823'.914 C2013-906627-6

Contents

Cover

Also by Roddy Doyle

About the Book

Title Page

Copyright

Jimmy Jazz

Also Available

About the Author

Jimmy Jazz

Jimmy waited while Outspan collected his oxygen from the cloakroom. He couldn’t wait to get outside, to breathe some cold air and walk through it. He thought about going out to the steps. But he stayed where he was. He wanted Outspan to be able to find him without having to go searching. He leaned against one of the pillars and watched the women.

He heard Outspan before he saw him.

– Mind your backs.

The three generations of women Jimmy was discreetly gawking at, one big tall family of outright fuckin’ gorgeousness – where did they come from, by the way, these Southside women? The fuckin’ Southside, obviously. But how? That was the question. How come they were so different to Northside girls? Not necessarily better looking. Definitely not. But what was it about them that made them look like they’d done the man who’d just performed inside a favour by turning up to see him? Was it just money? Or blood? Or luck, or ignorance? Jimmy didn’t know, and he didn’t really care. He just wanted to climb up on every one of them, even the granny. Especially the granny.

Actually, the one on the left might have been a granny as well. Anyway, he watched the women parting to make plenty of room, an M-fuckin’-50, for Outspan Foster as he shuffled through with his oxygen cylinder under his arm.

– Thanks, girls. Enjoy your night.

He landed in front of Jimmy.

– That took a while, said Jimmy.

– There was a different young one at the hatch, said Outspan.

He took a breath. It took a while.

– She thought – when I pointed, like. She thought I wanted the fuckin’ fire extinguisher. And she wouldn’t give it to me, even though I kept tellin’ her I didn’t fuckin’ want it. She was Polish or somethin’. Annyway.

Another breath – it hit the spot.

– Did you see your women back there, by the way?

They were outside now. Outspan turned and pressed his face to the window. Jimmy joined him.

– Yeah, he said.

– Fuckin’ amazin’, said Outspan. – Like walkin’ through Desperate Housewives. Every fuckin’ series.

– Did yeh watch it?

– No – fuck off.

They left the window and the woman and joined the crowds still coming out of the National Concert Hall.

– Pint? said Jimmy.

– Yeah, said Outspan. – I need one. After tha’.

– What did yeh think of it?

– Well, said Outspan. – For fuck sake.

All Jimmy had done was, he’d walked across the kitchen and he’d turned off the radio.

– I fuckin’ hate jazz, he’d said.

That was it.

But Aoife had exploded.

– And I fucking hate having to hear you saying you fucking hate jazz every time you hear it on the radio! Only on the radio! Because I wouldn’t dare – I wouldn’t fucking dare put it on my iPod. My fucking iPod! Just in case you accidentally heard it and fell down fucking dead.

– Sorry, he’d said.

– Grow up, Jimmy! Will you?

A daft request; he was forty-nine. But he loved her, and she was scaring him. So –

– Okay, he’d said.

There’d been something a bit evil about the way she’d looked back at him.

– Put the radio back on.

– Okay.

He poked the Roberts.

– Sit and listen, she said.

He did.

And it was fuckin’ agony.

– Did you enjoy that? she asked when the prick with the saxophone finally ran out of breath or died.

– Yeah, he said.

– Really?

– Yeah.

– Look at me when you’re talking to me, Jimmy.

He looked at her.

– Yeah, he said again, and he kept looking at her.

He’d always been a good liar. The sincere porky – Jimmy had invented it. And it must have worked again, because Aoife believed him. He’d convinced her that he didn’t hate jazz, that she was looking back at a man who’d grown up, who actually liked the shite she was forcing him to listen to.

Because he did. He hated jazz. Hated it, and he always had. He’d decided way back, when he was seventeen – he remembered the day – that he hated it, and he hadn’t budged since. He wasn’t a bigot; he was just right. Jazz was shite.

He remembered the day and the record player. And the tit. A girl called Sandra. A great-looking young one in the same year as him, the same school

. This was a few months before Jimmy left school for good. They were both seventeen. It was a Sunday afternoon and it was raining, so they’d gone to her house to play a few records and that. Jimmy had his new copy of London Calling with him, bought with some the money he’d made selling bootleg videos of The Life of Brian in school, to the teachers. Sandra wasn’t much into the music; she hadn’t a clue. But she thought the cover was cool and that made Jimmy cool enough because he was carrying it. Anyway, she’d said the house would be empty because her parents always went for a drive on Sundays and she was that weird thing in Barrytown, an only child. A free gaff and a record player! The Clash and maybe a ride, or something not too far from a ride. On a fuckin’ Sunday! Jimmy was searching for his house key before he remembered that it was her house, not his, they were going to. She was in no hurry, the wagon. But they eventually got there. And the house wasn’t empty at all. Her da was in the room with the record player and the cunt was playing Charlie Parker.

Jimmy didn’t know that it was Charlie Parker, just that it was shite. They sat on two hard chairs in the kitchen. Her ma had gone to see a nearly dead auntie or something, and that was why her prick of a da was alone with his Complan and the record player. They sat beside each other, damp and – Jimmy anyway – frustrated as fuck. And the shite from the front room, the squeaks and fuckin’ squawks from – Jimmy thought it might be a sax but he wasn’t sure. But he hated it. They kissed, but her eyes kept looking at the kitchen door; it was like trying to get off with a nervous deer. And your man in the front room was fucking around with the volume. It was nerve wracking, but Jimmy did it anyway. His self-respect demanded it – he went for her tit. She yelped and nearly bit the tongue off him.

Fuckin’ jazz.

Her da had been to blame, of course, not the jazz. The fuckin’ clown. He’d died a few months back, Jimmy’s own da had told him.

– Died cuttin’ the grass.

– Really?

– The lawnmower kept goin’, apparently, said his da. – I’d hate tha’.

– Dyin’?

– Well yeah, said Jimmy’s da. –’Course. But no. I mean, I’d like to think the lawnmower would have the fuckin’ decency to stop an’ turn itself off. Your last act, imagine. Hearin’ the lawnmower fuckin’ off down the garden without yeh.

Jimmy had been tempted to go to the funeral, to see how the Sandra one was looking. But he didn’t go. He’d like to have said hello, and told her he was sorry for her troubles – she’d been sound, he remembered – but there might have been jazz. The da’s favourite record or some wanker with a sax thinking he was Charlie Parker, in the church. The only thing worse than Charlie Parker was some fat-fingered cunt who thought he was Charlie Parker.

So, the jazz had stayed shite long after Jimmy’s tongue had stopped bleeding and he’d forgiven Sandra. It was the only thing he still clung to, his only real conviction. He’d no interest in God or politics. He’d been through cancer and chemo. He’d been ready for death. He’d confronted his demons – and they were all jazz lovers.

He hated jazz but he loved his wife very much. So he’d made the effort and pretended to enjoy it while she was basting the chicken.

– Who’s that? he’d asked.

– Does it matter? she’d answered, and she’d held up the baster like a weeping sword.

– Just curious, he’d said. –It’s interestin’.

For fuck sake.

Jazz.

Anyway, she’d tortured him for weeks, testing his endurance every time he went near the kitchen. She was always in there, ready to ambush him. He became convinced of that. She never seemed to go out any more, or even into one of the other rooms. Filling and emptying the dishwasher, tidying up after the dinner – these used to be Jimmy’s jobs. He’d stick his iPod in the dock on top of the fridge and beaver away happily to My Bloody Valentine or Al Green. Now though, he found her iPod where he needed to put his iPod, and he was afraid to touch it. And filling the dishwasher to the Brad Mehldau Trio – it wasn’t fuckin’ natural. But he smiled big at Aoife and resisted the temptation – the urge, the order – to climb into the dishwasher and shut the door after him.

She was evil. He’d never considered that possibility before. She’d always been nice. Funny and nice and sexy as fuck – that had always been the woman he’d married. Considerate and efficient – good at the sums. A brilliant mother. Gorgeous, enthusiastic. But never evil.

But she was.

She turned to him in the bed – this was a few weeks before Christmas. She slid her leg across him and a hand went over his chest, stayed for a second, continued, and she lifted herself onto him. She made sure her hair brushed his face, then sat up. She leaned out – the movement reminded Jimmy of back in the day, in his flat, his bedsit, before they’d married, before they really knew each other. He remembered how she’d leaned out like that, maybe just the once but he remembered it clearly, to get a condom from beside the bed. He thought of that this time. Didn’t really think it – he lived it. It was like they were kids again, in their early twenties, before their own kids, the mortgage, the weight, the vasectomy. The cancer. He expected to look up and see her tearing the foil with her teeth – hair longer, face a bit younger. But she came back with her iPod. She stared down at him while she slowly unwound the earphones. Then she placed the iPod on his chest and brought her hands to his face, to his ears. She leaned down, over him, as she pushed an earphone into each of his ears. Then she pressed > and grabbed his wrists, held him down and made him ride her while he was forced to listen to My Favorite Things by John Coltrane. The lads in Guantanamo hadn’t a clue.

Then there was the Christmas present.

The Christmas before, she’d given him a trumpet. Just before he’d started the chemotherapy. When he’d been half-thinking that it would be – might be – his last Christmas. She’d bought him a trumpet and, with that and the invitation to learn how to play it, she’d told him he’d live.

This time though, a year later, she handed him an envelope.

– What’s this?

– Open it.

– What is it, but?

– Go on, she said.

She was smiling as she spoke.

He tore at the envelope.

– Careful.

He took out two tickets – two gig tickets.

– Great, he said. –Springsteen?

But he read the name.

– Keith Jarrett?

– Yes.

– Who’s he?

– Who the fuck is he? said Outspan.

– Keith Jarrett, said Jimmy. – Have yeh not heard of him, no?

– The cunt from Boyzone, said Outspan.

– No, said Jimmy.

– Then I’m lost, said Outspan. –I’ve run out o’ Keiths.

– He’s a piano player.

– Wha’? said Outspan. –Like Richard Clayderman? Remember him?

– I do, yeah.

Richard Clayderman had driven Jimmy out of the house when he was twenty-two. His da had confessed it years later.

– It was fuckin’ torture, said his da.

– Hang on, said Jimmy.

This was about five years ago, when the two of them were having a pint.

– You’re sayin’ – wha’? You an’ Ma conspired –

– Good word.

– Fuck off a minute, said Jimmy. –You an’ ma decided it was time for me to go.

– Exactly – yeah.

– Why didn’t yis just tell me?

– Ah, we couldn’t do tha’, said his da. –It would’ve been too blunt.

– For fuck sake.

– It was your mother’s idea.

– Throwin’ me ou’?

– No, said his da. –Tha’ was me. No, Richard Clayderman.

An’ there, yeh see. That’s me point. You said – just there – we threw you ou’. But we didn’t. You left of your own accord.

– I couldn’t take anny more.

– I

nearly went with yeh, said his da. – It was touch an’ go.

It had gone on for weeks, the Clayderman assault. His ma had even bought a tape recorder for the kitchen, so Jimmy couldn’t have a bit of toast in the morning without having Ballade Pour Adeline shoved into, not just his ears, his fuckin’ eyes. And his da humming along with it, the prick.

– I’m not proud of it.

– Yeh should be fuckin’ ashamed of yourself, said Jimmy.

– I was tough love, son. An’ it worked.

– Why? said Jimmy.

– Why wha’?

– Why did yis want me ou’?

He’d lived more than half his life since then, but this was still shocking, deeply hurtful news.

– Well, said his da. –You were an insufferable little cunt.

– Oh.

– Back then, said his da. –You’re not as bad these days.

– No, Jimmy told Outspan now. –Nothin’ like Richard Clayderman.

– Is that all he does, but? said Outspan.

– Wha’ dyeh mean?

– Play the fuckin’ piano, said Outspan. –Is tha’ all he fuckin’ does?

– Think so, said Jimmy.

It had been another part of the present, a strict condition. Aoife wouldn’t be going with him.

– How come? Jimmy asked her.

He tried not to sound too suspicious.

– So you won’t think I really got the tickets for myself, she said.

– I don’t, he lied.

She smiled.

– You’re sweet, she said.

She was evil.

– Ask one of your friends.

And Jimmy had thought of Outspan. Outspan liked his music and he was always good crack, although he was a bit unreliable. Making a date with Outspan wasn’t a safe bet, given the fact that he was dying of cancer. (That was how they’d met up again, a few years back; they’d both been coming out of chemo.) But Jimmy had looked at Outspan. This was in early January, and they were in the bagel place at the side of Arnott’s. And he’d decided that there might be a few months left in him, if his ability to murder a roast beef bagel was anything to go by.

So he’d asked him. And Outspan had wiped his mouth and said okay.