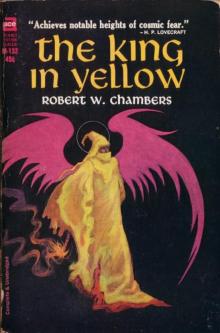

The King in Yellow

Robert W. Chambers

Produced by Suzanne Shell, Beth Trapaga, Charles Franks,and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team

THE KING IN YELLOW

BY

ROBERT W. CHAMBERS

Original publication date: 1895

THE KING IN YELLOWIS DEDICATEDTOMY BROTHER

Along the shore the cloud waves break, The twin suns sink beneath the lake, The shadows lengthen In Carcosa.

Strange is the night where black stars rise, And strange moons circle through the skies But stranger still is Lost Carcosa.

Songs that the Hyades shall sing, Where flap the tatters of the King, Must die unheard in Dim Carcosa.

Song of my soul, my voice is dead; Die thou, unsung, as tears unshed Shall dry and die in Lost Carcosa.

Cassilda's Song in "The King in Yellow," Act i, Scene 2.

THE REPAIRER OF REPUTATIONS

I

"Ne raillons pas les fous; leur folie dure plus longtemps quela notre.... Voila toute la difference."

Toward the end of the year 1920 the Government of the United States hadpractically completed the programme, adopted during the last months ofPresident Winthrop's administration. The country was apparently tranquil.Everybody knows how the Tariff and Labour questions were settled. The warwith Germany, incident on that country's seizure of the Samoan Islands,had left no visible scars upon the republic, and the temporary occupationof Norfolk by the invading army had been forgotten in the joy overrepeated naval victories, and the subsequent ridiculous plight of GeneralVon Gartenlaube's forces in the State of New Jersey. The Cuban andHawaiian investments had paid one hundred per cent and the territory ofSamoa was well worth its cost as a coaling station. The country was in asuperb state of defence. Every coast city had been well supplied with landfortifications; the army under the parental eye of the General Staff,organized according to the Prussian system, had been increased to 300,000men, with a territorial reserve of a million; and six magnificentsquadrons of cruisers and battle-ships patrolled the six stations of thenavigable seas, leaving a steam reserve amply fitted to control homewaters. The gentlemen from the West had at last been constrained toacknowledge that a college for the training of diplomats was as necessaryas law schools are for the training of barristers; consequently we were nolonger represented abroad by incompetent patriots. The nation wasprosperous; Chicago, for a moment paralyzed after a second great fire, hadrisen from its ruins, white and imperial, and more beautiful than the whitecity which had been built for its plaything in 1893. Everywhere goodarchitecture was replacing bad, and even in New York, a sudden craving fordecency had swept away a great portion of the existing horrors. Streetshad been widened, properly paved and lighted, trees had been planted,squares laid out, elevated structures demolished and underground roadsbuilt to replace them. The new government buildings and barracks were finebits of architecture, and the long system of stone quays which completelysurrounded the island had been turned into parks which proved a god-sendto the population. The subsidizing of the state theatre and state operabrought its own reward. The United States National Academy of Design wasmuch like European institutions of the same kind. Nobody envied theSecretary of Fine Arts, either his cabinet position or his portfolio. TheSecretary of Forestry and Game Preservation had a much easier time, thanksto the new system of National Mounted Police. We had profited well by thelatest treaties with France and England; the exclusion of foreign-bornJews as a measure of self-preservation, the settlement of the newindependent negro state of Suanee, the checking of immigration, the newlaws concerning naturalization, and the gradual centralization of power inthe executive all contributed to national calm and prosperity. When theGovernment solved the Indian problem and squadrons of Indian cavalryscouts in native costume were substituted for the pitiable organizationstacked on to the tail of skeletonized regiments by a former Secretary ofWar, the nation drew a long sigh of relief. When, after the colossalCongress of Religions, bigotry and intolerance were laid in their gravesand kindness and charity began to draw warring sects together, manythought the millennium had arrived, at least in the new world which afterall is a world by itself.

But self-preservation is the first law, and the United States had to lookon in helpless sorrow as Germany, Italy, Spain and Belgium writhed in thethroes of Anarchy, while Russia, watching from the Caucasus, stooped andbound them one by one.

In the city of New York the summer of 1899 was signalized by thedismantling of the Elevated Railroads. The summer of 1900 will live inthe memories of New York people for many a cycle; the Dodge Statue wasremoved in that year. In the following winter began that agitation forthe repeal of the laws prohibiting suicide which bore its final fruit inthe month of April, 1920, when the first Government Lethal Chamber wasopened on Washington Square.

I had walked down that day from Dr. Archer's house on Madison Avenue,where I had been as a mere formality. Ever since that fall from my horse,four years before, I had been troubled at times with pains in the back ofmy head and neck, but now for months they had been absent, and the doctorsent me away that day saying there was nothing more to be cured in me. Itwas hardly worth his fee to be told that; I knew it myself. Still I didnot grudge him the money. What I minded was the mistake which he made atfirst. When they picked me up from the pavement where I lay unconscious,and somebody had mercifully sent a bullet through my horse's head, I wascarried to Dr. Archer, and he, pronouncing my brain affected, placed mein his private asylum where I was obliged to endure treatment forinsanity. At last he decided that I was well, and I, knowing that my mindhad always been as sound as his, if not sounder, "paid my tuition" as hejokingly called it, and left. I told him, smiling, that I would get evenwith him for his mistake, and he laughed heartily, and asked me to callonce in a while. I did so, hoping for a chance to even up accounts, buthe gave me none, and I told him I would wait.

The fall from my horse had fortunately left no evil results; on thecontrary it had changed my whole character for the better. From a lazyyoung man about town, I had become active, energetic, temperate, andabove all--oh, above all else--ambitious. There was only one thing whichtroubled me, I laughed at my own uneasiness, and yet it troubled me.

During my convalescence I had bought and read for the first time, _TheKing in Yellow_. I remember after finishing the first act that itoccurred to me that I had better stop. I started up and flung the bookinto the fireplace; the volume struck the barred grate and fell open onthe hearth in the firelight. If I had not caught a glimpse of the openingwords in the second act I should never have finished it, but as I stoopedto pick it up, my eyes became riveted to the open page, and with a cry ofterror, or perhaps it was of joy so poignant that I suffered in everynerve, I snatched the thing out of the coals and crept shaking to mybedroom, where I read it and reread it, and wept and laughed and trembledwith a horror which at times assails me yet. This is the thing thattroubles me, for I cannot forget Carcosa where black stars hang in theheavens; where the shadows of men's thoughts lengthen in the afternoon,when the twin suns sink into the lake of Hali; and my mind will bear forever the memory of the Pallid Mask. I pray God will curse the writer, asthe writer has cursed the world with this beautiful, stupendous creation,terrible in its simplicity, irresistible in its truth--a world which nowtrembles before the King in Yellow. When the French Government seized thetranslated copies which had just arrived in Paris, London, of course,became eager to read it. It is well known how the book spread like aninfectious disease, from city to city, from continent to continent,barred out here, confiscated there, denounced by Press and pulpit,censured even by the most advanced of literary anarchists. No definiteprinciples had been violated in those wicked pages, no doctrinepromulgated, no convictions outraged. It could not be judged by any

knownstandard, yet, although it was acknowledged that the supreme note of arthad been struck in _The King in Yellow_, all felt that human naturecould not bear the strain, nor thrive on words in which the essence ofpurest poison lurked. The very banality and innocence of the first actonly allowed the blow to fall afterward with more awful effect.

It was, I remember, the 13th day of April, 1920, that the firstGovernment Lethal Chamber was established on the south side of WashingtonSquare, between Wooster Street and South Fifth Avenue. The block whichhad formerly consisted of a lot of shabby old buildings, used as cafesand restaurants for foreigners, had been acquired by the Government inthe winter of 1898. The French and Italian cafes and restaurants weretorn down; the whole block was enclosed by a gilded iron railing, andconverted into a lovely garden with lawns, flowers and fountains. In thecentre of the garden stood a small, white building, severely classical inarchitecture, and surrounded by thickets of flowers. Six Ionic columnssupported the roof, and the single door was of bronze. A splendid marblegroup of the "Fates" stood before the door, the work of a young Americansculptor, Boris Yvain, who had died in Paris when only twenty-three yearsold.

The inauguration ceremonies were in progress as I crossed UniversityPlace and entered the square. I threaded my way through the silent throngof spectators, but was stopped at Fourth Street by a cordon of police. Aregiment of United States lancers were drawn up in a hollow square roundthe Lethal Chamber. On a raised tribune facing Washington Park stood theGovernor of New York, and behind him were grouped the Mayor of NewYork and Brooklyn, the Inspector-General of Police, the Commandant ofthe state troops, Colonel Livingston, military aid to the President of theUnited States, General Blount, commanding at Governor's Island,Major-General Hamilton, commanding the garrison of New York and Brooklyn,Admiral Buffby of the fleet in the North River, Surgeon-GeneralLanceford, the staff of the National Free Hospital, Senators Wyse andFranklin of New York, and the Commissioner of Public Works. The tribunewas surrounded by a squadron of hussars of the National Guard.

The Governor was finishing his reply to the short speech of theSurgeon-General. I heard him say: "The laws prohibiting suicide andproviding punishment for any attempt at self-destruction have beenrepealed. The Government has seen fit to acknowledge the right of man toend an existence which may have become intolerable to him, throughphysical suffering or mental despair. It is believed that the communitywill be benefited by the removal of such people from their midst. Sincethe passage of this law, the number of suicides in the United States hasnot increased. Now the Government has determined to establish a LethalChamber in every city, town and village in the country, it remains to beseen whether or not that class of human creatures from whose despondingranks new victims of self-destruction fall daily will accept the reliefthus provided." He paused, and turned to the white Lethal Chamber. Thesilence in the street was absolute. "There a painless death awaits himwho can no longer bear the sorrows of this life. If death is welcome lethim seek it there." Then quickly turning to the military aid of thePresident's household, he said, "I declare the Lethal Chamber open," andagain facing the vast crowd he cried in a clear voice: "Citizens of NewYork and of the United States of America, through me the Governmentdeclares the Lethal Chamber to be open."

The solemn hush was broken by a sharp cry of command, the squadron ofhussars filed after the Governor's carriage, the lancers wheeled andformed along Fifth Avenue to wait for the commandant of the garrison, andthe mounted police followed them. I left the crowd to gape and stare atthe white marble Death Chamber, and, crossing South Fifth Avenue, walkedalong the western side of that thoroughfare to Bleecker Street. Then Iturned to the right and stopped before a dingy shop which bore the sign:

HAWBERK, ARMOURER.

I glanced in at the doorway and saw Hawberk busy in his little shop atthe end of the hall. He looked up, and catching sight of me cried in hisdeep, hearty voice, "Come in, Mr. Castaigne!" Constance, his daughter,rose to meet me as I crossed the threshold, and held out her prettyhand, but I saw the blush of disappointment on her cheeks, and knewthat it was another Castaigne she had expected, my cousin Louis. Ismiled at her confusion and complimented her on the banner she wasembroidering from a coloured plate. Old Hawberk sat riveting the worngreaves of some ancient suit of armour, and the ting! ting! ting! of hislittle hammer sounded pleasantly in the quaint shop. Presently hedropped his hammer, and fussed about for a moment with a tiny wrench.The soft clash of the mail sent a thrill of pleasure through me. Iloved to hear the music of steel brushing against steel, the mellowshock of the mallet on thigh pieces, and the jingle of chain armour.That was the only reason I went to see Hawberk. He had never interestedme personally, nor did Constance, except for the fact of her being inlove with Louis. This did occupy my attention, and sometimes even keptme awake at night. But I knew in my heart that all would come right,and that I should arrange their future as I expected to arrange that ofmy kind doctor, John Archer. However, I should never have troubledmyself about visiting them just then, had it not been, as I say, thatthe music of the tinkling hammer had for me this strong fascination. Iwould sit for hours, listening and listening, and when a stray sunbeamstruck the inlaid steel, the sensation it gave me was almost too keento endure. My eyes would become fixed, dilating with a pleasure thatstretched every nerve almost to breaking, until some movement of theold armourer cut off the ray of sunlight, then, still thrillingsecretly, I leaned back and listened again to the sound of thepolishing rag, swish! swish! rubbing rust from the rivets.

Constance worked with the embroidery over her knees, now and then pausingto examine more closely the pattern in the coloured plate from theMetropolitan Museum.

"Who is this for?" I asked.

Hawberk explained, that in addition to the treasures of armour in theMetropolitan Museum of which he had been appointed armourer, he alsohad charge of several collections belonging to rich amateurs. This was themissing greave of a famous suit which a client of his had traced to alittle shop in Paris on the Quai d'Orsay. He, Hawberk, had negotiated forand secured the greave, and now the suit was complete. He laid down hishammer and read me the history of the suit, traced since 1450 from ownerto owner until it was acquired by Thomas Stainbridge. When his superbcollection was sold, this client of Hawberk's bought the suit, and sincethen the search for the missing greave had been pushed until it was,almost by accident, located in Paris.

"Did you continue the search so persistently without any certainty of thegreave being still in existence?" I demanded.

"Of course," he replied coolly.

Then for the first time I took a personal interest in Hawberk.

"It was worth something to you," I ventured.

"No," he replied, laughing, "my pleasure in finding it was my reward."

"Have you no ambition to be rich?" I asked, smiling.

"My one ambition is to be the best armourer in the world," he answeredgravely.

Constance asked me if I had seen the ceremonies at the Lethal Chamber.She herself had noticed cavalry passing up Broadway that morning, and hadwished to see the inauguration, but her father wanted the bannerfinished, and she had stayed at his request.

"Did you see your cousin, Mr. Castaigne, there?" she asked, with theslightest tremor of her soft eyelashes.

"No," I replied carelessly. "Louis' regiment is manoeuvring out inWestchester County." I rose and picked up my hat and cane.

"Are you going upstairs to see the lunatic again?" laughed old Hawberk.If Hawberk knew how I loathe that word "lunatic," he would never use itin my presence. It rouses certain feelings within me which I do not careto explain. However, I answered him quietly: "I think I shall drop in andsee Mr. Wilde for a moment or two."

"Poor fellow," said Constance, with a shake of the head, "it must be hardto live alone year after year poor, crippled and almost demented. It isvery good of you, Mr. Castaigne, to visit him as often as you do."

"I think he is vicious," observed Hawberk, beginning again with hishammer. I listened to

the golden tinkle on the greave plates; when he hadfinished I replied:

"No, he is not vicious, nor is he in the least demented. His mind is awonder chamber, from which he can extract treasures that you and I wouldgive years of our life to acquire."'

Hawberk laughed.

I continued a little impatiently: "He knows history as no one else couldknow it. Nothing, however trivial, escapes his search, and his memory isso absolute, so precise in details, that were it known in New York thatsuch a man existed, the people could not honour him enough."

"Nonsense," muttered Hawberk, searching on the floor for a fallen rivet.

"Is it nonsense," I asked, managing to suppress what I felt, "is itnonsense when he says that the tassets and cuissards of the enamelledsuit of armour commonly known as the 'Prince's Emblazoned' can be foundamong a mass of rusty theatrical properties, broken stoves andragpicker's refuse in a garret in Pell Street?"

Hawberk's hammer fell to the ground, but he picked it up and asked, witha great deal of calm, how I knew that the tassets and left cuissard weremissing from the "Prince's Emblazoned."

"I did not know until Mr. Wilde mentioned it to me the other day. He saidthey were in the garret of 998 Pell Street."

"Nonsense," he cried, but I noticed his hand trembling under his leathernapron.

"Is this nonsense too?" I asked pleasantly, "is it nonsense when Mr.Wilde continually speaks of you as the Marquis of Avonshire and of MissConstance--"

I did not finish, for Constance had started to her feet with terrorwritten on every feature. Hawberk looked at me and slowly smoothed hisleathern apron.

"That is impossible," he observed, "Mr. Wilde may know a great manythings--"

"About armour, for instance, and the 'Prince's Emblazoned,'" Iinterposed, smiling.

"Yes," he continued, slowly, "about armour also--may be--but he is wrongin regard to the Marquis of Avonshire, who, as you know, killed hiswife's traducer years ago, and went to Australia where he did not longsurvive his wife."

"Mr. Wilde is wrong," murmured Constance. Her lips were blanched, but hervoice was sweet and calm.

"Let us agree, if you please, that in this one circumstance Mr. Wilde iswrong," I said.