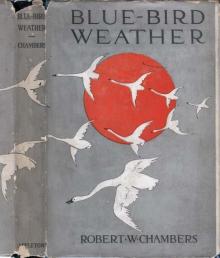

Blue-Bird Weather

Robert W. Chambers

BLUE-BIRD WEATHER

* * * * *

Works of Robert W. Chambers

The Streets Of Ascalon Blue-Bird Weather Japonette The Adventures of a Modest Man The Danger Mark Special Messenger The Firing Line The Younger Set The Fighting Chance Some Ladies in Haste The Tree of Heaven The Tracer of Lost Persons A Young Man in a Hurry Lorraine Maids of Paradise Ashes of Empire The Red Republic Outsiders The Common Law Ailsa Paige The Green Mouse Iole The Reckoning The Maid-at-Arms Cardigan The Haunts of Men The Mystery of Choice The Cambric Mask The Maker of Moons The King in Yellow In Search of the Unknown The Conspirators A King and a Few Dukes In the Quarter

For Children

Garden-Land Forest-Land River-Land Mountain-Land Orchard-Land Outdoor-Land Hide and Seek in Forest-Land

D. APPLETON AND COMPANY, New York

* * * * *

BLUE-BIRD WEATHER

by

ROBERT W. CHAMBERS

[Decoration]

With Illustrations by Charles Dana Gibson

"She trotted away to Marche's door and tapped softly." [Page 140]]

D. Appleton and CompanyNew York and London :: MCMXII

Copyright, 1912, byRobert W. Chambers

Copyright, 1911, by International Magazine Company

Published October, 1912

Published in the United States of America

TO JOSEPH LEE OF NEEDWOOD FOREST

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

PAGE

"She trotted away to Marche's door and tapped softly." _Frontispiece_

"She said gravely: 'I am afraid it will be blue-bird weather.'" 14

"'Well,' he said pleasantly, 'what comes next, Miss Herold?'" 26

"'I'm _so_ sorry, Jim.'" 33

"They ate their luncheon there together." 88

"'Jim,' he said, 'where did you live?'" 99

"'He tells you that he--he is in love with you?'" 127

BLUE-BIRD WEATHER

I

It was now almost too dark to distinguish objects; duskier and vaguerbecame the flat world of marshes, set here and there with cypress andbounded only by far horizons; and at last land and water disappearedbehind the gathered curtains of the night. There was no sound from thewaste except the wind among the withered reeds and the furrowing splashof wheel and hoof over the submerged causeway.

The boy who was driving had scarcely spoken since he strapped Marche'sgun cases and valise to the rear of the rickety wagon at the railroadstation. Marche, too, remained silent, preoccupied with his ownreflections. Wrapped in his fur-lined coat, arms folded, he sat doubledforward, feeling the Southern swamp-chill busy with his bones. Now andthen he was obliged to relight his pipe, but the cold bit at hisfingers, and he hurried to protect himself again with heavy gloves.

The small, rough hands of the boy who was driving were naked, andfinally Marche mentioned it, asking the child if he were not cold.

"No, sir," he said, with a colorless brevity that might have beenshyness or merely the dull indifference of the very poor, accustomed todiscomfort.

"Don't you feel cold at all?" persisted Marche kindly.

"No, sir."

"I suppose you are hardened to this sort of weather?"

"Yes, sir."

By the light of a flaming match, Marche glanced sideways at him as hedrew his pipe into a glow once more, and for an instant the boy's grayeyes flickered toward his in the flaring light. Then darkness maskedthem both again.

"Are you Mr. Herold's son?" inquired the young man.

"Yes, sir," almost sullenly.

"How old are you?"

"Eleven."

"You're a big boy, all right. I have never seen your father. He is atthe clubhouse, no doubt."

"Yes, sir," scarcely audible.

"And you and he live there all alone, I suppose?"

"Yes, sir." A moment later the boy added jerkily, "And my sister," asthough truth had given him a sudden nudge.

"Oh, you have a sister, too?"

"Yes, sir."

"That makes it very jolly for you, I fancy," said Marche pleasantly.There was no reply to the indirect question.

His pipe had gone out again, and he knocked the ashes from it andpocketed it. For a while they drove on in silence, then Marche peeredimpatiently through the darkness, right and left, in an effort to see;and gave it up.

"You must know this road pretty well to be able to keep it," he said."As for me, I can't see anything except a dirty little gray star upaloft."

"The horse knows the road."

"I'm glad of that. Have you any idea how near we are to the house?"

"Half a mile. That's Rattler Creek, yonder."

"How the dickens can you tell?" asked Marche curiously. "You can't seeanything in the dark, can you?"

"I don't know how I can tell," said the boy indifferently.

Marche smiled. "A sixth sense, probably. What did you say your name is?"

"Jim."

"And you're eleven? You'll be old enough to have a gun very soon, Jim.How would you like to shoot a real, live wild duck?"

"I _have_ shot plenty."

Marche laughed. "Good for you, Jimmy. What did the gun do to you? Kickyou flat on your back?"

The boy said gravely: "Father's gun is too big for me. I have to rest iton the edge of the blind when I fire."

"Do you shoot from the blinds?"

"Yes, sir."

Marche relapsed into smiling silence. In a few moments he was thinkingof other things--of this muddy island which had once been the propertyof a club consisting of five carefully selected and wealthy members, andwhich, through death and resignation, had now reverted to him. Why hehad ever bought in the shares, as one by one the other members eitherdied or dropped out, he did not exactly know. He didn't care very muchfor duck shooting. In five years he had not visited the club; and why hehad come here this year for a week's sport he scarcely knew, except thathe had either to go somewhere for a rest or ultimately be carried,kicking, into what his slangy doctor called the "funny house."

So here he was, on a cold February night, and already nearly at hisdestination; for now he could make out a light across the marsh, andfrom dark and infinite distances the east wind bore the solemn rumor ofthe sea, muttering of wrecks and death along the Atlantic sands beyondthe inland sounds.

"Well, Jim," he said, "I never thought I'd survive this drive, but herewe are, and still alive. Are you frozen solid, you poor boy?"

The boy smiled, shyly, in negation, as they drove into the bar of lightfrom the kitchen window and stopped. Marche got down very stiffly. Thekitchen door opened at the same moment, and a woman's figure appeared inthe lamplight--a young girl, slender, bare armed, drying her fingers asshe came down the steps to offer a small, weather-roughened hand toMarche.

"My brother will show you to your room," she said. "Supper will be readyin a few minutes."

So he thanked her and went away with Jim, relieving the boy of thevalise and one gun-case, and presently came to the quarters prepared forhim. The room was rough, with its unceiled walls of yellow pine, achair, washstand, bed, and a nail or two for his wardrobe. It had beenthe affectation of the wealthy men composing the Foam Island Duck Clubto exist almost primitively when on the business of duck shooting, incontradistinction to the overfed luxury of other millionairesinhabiting other more luxuriously appointed shooting-boxes along theChesapeake.

The Foam Island

Club went in heavily for simplicity, as far as thetwo-story shanty of a clubhouse was concerned; but their island was oneof the most desirable in the entire region, and their live decoys themost perfectly trained and cared for.

Marche, washing his tingling fingers and visage in icy water, ratherwished, for a moment, that the club had installed modern plumbing; butdelectable odors from the kitchen put him into better humor, andpresently he went off down the creaking and unpainted stairs to warmhimself at a big stove until summoned to the table.

He was summoned in a few moments by the same girl who had greeted him;and she also waited on him at table, placing before him in turn hissteaming soup, a platter of fried bass and smoking sweet potatoes, thenthe inevitable broiled canvas-back duck with