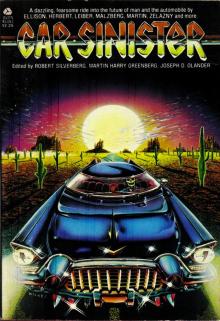

Car Sinister

Robert Silverberg

Jerry eBooks

No copyright 2019 by Jerry eBooks

No rights reserved. All parts of this book may be reproduced in any form and by any means for any purpose without any prior written consent of anyone.

CHROME

FUTURES

Cruise into tomorrow with the likes of Harlan Ellison, Frank Herbert, Harry Harrison, Frank M. Robinson, and Roger Zelazny at the wheel! Here are twenty streamlined visions of the automobile as symbol of man’s dreams, agent of society’s destruction, and link between modem times and the car-dominated city at the end of time.

There are stories of automobile invasions, deathcars with minds of their own, time-warped highways, traffic wars, service stations of the future, romance in a twenty-first century used-car lot, and a pregnant Rambler American. There is even a visionary solution to the fuel crisis!

CAR SINISTER is an original publication of Avon Books.

This work has never before appeared in book form.

AVON BOOKS

A division of

The Hearst Corporation

959 Eighth Avenue

New York, New York 10019

Copyright © 1979 by Robert Silverberg, Martin Greenberg,

Joseph Olander

Published by arrangement with the editors.

Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 79-87803

ISBN: 0-380-45393-2

All rights reserved, which includes the right

to reproduce this book or portions thereof in

any form whatsoever. For information address

Scott Meredith Literary Agency, 845 Third Avenue,

New York, New York 10022

First Avon Printing, July, 1979

AVON TRADEMARK REG. U.S. PAT. OFF. AND IN

OTHER COUNTRIES, MARCA REGISTRADA,

HECHO EN U.S.A.

Printed in the U.S.A.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

“Devil Car,” by Roger Zelazny, copyright © 1965 by Galaxy Publishing Corporation. Reprinted by permission of the author and Henry Morrison Inc., his agents.

“Vampire Ltd,” by Josef Nesvadba, copyright © 1964 by Josef Nesvadba. Reprinted by permission of the author and his agents, the Dilia Theatrical and Literary Agency.

“A Plague of Cars,” by Leonard Tushnet, from New Dimensions, copyright © 1971 by Robert Silverberg. Reprinted by permission of the author’s estate.

“Auto-da-Fé,” by Roger Zelazny, copyright © 1967 by Harlan Ellison for Dangerous Visions. Reprinted by permission of the author and Henry Morrison Inc., his agents.

“Traffic Problem,” by William Earls, copyright © 1970 by UPD Publishing Corporation. Reprinted by permission of the author.

“Station HR972,” by Kenneth Bulmer, copyright © 1967 by Kenneth Bulmer. Reprinted by permission of the author.

A Day on Death Highway,” by H. Chandler Elliott, copyright © 1963 by the Galaxy Publishing Corporation. Reprinted by permission of the author’s estate.

The Greatest Car in the World,” by Harry Harrison, copyright © 1966 by New Worlds SF, © 1970 by Harry Harrison. Reprinted by permission of the author.

“The Roads, the Roads, the Beautiful Roads,” by Avram Davidson, copyright © 1969 by Damon Knight. Reprinted by permission of the author and his agent, Kirby McCauley.

“The Exit to San Breta,” by George R.R. Martin, copyright© 1971 by Ultimate Publishing Company, Inc. Reprinted by permission of the author’s agent, Kirby McCauley.

“Car Sinister,” by Gene Wolfe, from The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction, copyright © 1969 by Mercury Press, Inc. Reprinted by permission of the author and the author’s agent, Virginia Kidd.

“Interurban Queen,” by R.A. Lafferty, copyright © 1970, 1978 by R.A. Lafferty. Reprinted by permission of the author and the author’s agent, Virginia Kidd.

“Waves of Ecology,” by Leonard Tushnet, from The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction, copyright © 1974 by Mercury Press Inc. Reprinted by permission of the author’s estate.

“The Mary Celeste Move” by Frank Herbert, copyright © 1964 by Condi Nast Publications. Reprinted by permission of the author’s agent, Lurton Blassingame.

“X Marks the Pedwalk,” by Fritz Leiber, copyright © 1963 by Galaxy Publishing Corporation. Reprinted by permission of the author and his agent, Robert P. Mills.

“Wheels,” by Robert Thurston, copyright © 1971 by Robert Thurston. Reprinted by permission of Robert Thurston and the Julian Bach Literary Agency.

“Sedan Deville,” by Barry N. Malzberg, from The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction, copyright © 1974 by Mercury Press, Inc. Reprinted by permission of the author.

“Romance in a Twenty-First Century Used-Car Lot,” by Robert F. Young, from The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction, copyright © 1960 by Mercury Press Inc., © 1965 by Robert F. Young. Reprinted by permission of the author.

“East Wind, West Wind,” by Frank M. Robinson, copyright © 1970 by Frank M. Robinson. Reprinted by permission of Curtis Brown, Ltd.

“Along the Scenic Route,” by Harlan Ellison, copyright © 1969 by Harlan Ellison. Reprinted by permission of the author and the author’s agent, Robert P. Mills, Ltd., New York.

CONTENTS

Introduction

Devil Car

Roger Zelazny

Vampire, Ltd.

Josef Nesvadba

A Plague of Cars

Leonard Tushnet

Auto-da-Fé

Roger Zelazny

Traffic Problem

William Earls

Station HR972

Kenneth Bulmer

A Day on Death Highway

Chandler Elliott

The Greatest Car in the World

Harry Harrison

The Roads, the Roads, the Beautiful Roads

Avram Davidson

The Exit to San Breta

George R.R. Martin

Car Sinister

Gene Wolfe

Interurban Queen

R.A. Lafferty

Waves of Ecology

Leonard Tushnet

The Mary Celeste Move

Frank Herbert

X Marks the Pedwalk

Fritz Leiber

Wheels

Robert Thurston

Sedan Deville

Barry N. Malzberg

Romance in a Twenty-first Century Used Car Lot

Robert F. Young

East Wind, West Wind

Frank M. Robinson

Along the Scenic Route

Harlan Ellison

INTRODUCTION

This history of the automobile and the evolution of science fiction in the United States have a number of things in common. For example, the early years of science fiction were characterized by an almost boundless faith in science and technology, a faith whose central creed held that the solution of the world’s problems was at hand if only the scientist was allowed to do his work. This optimism began to slow in the pages of the American SF magazines with the Great Depression and the approach of World War II, and it was to be dealt a major (and nearly fatal) blow at Hiroshima.

Similarly, many attitudes at the dawn of the automobile age can be described as “utopian” if not naive. It was widely believed that the coming horseless age would result in the transformation of urban areas into Gardens of Eden: “The improvement in city conditions by the general adoption of the motorcar can hardly be overestimated. Streets clean, dustless, and odorless, with light rubber-tired vehicles moving swiftly and noiselessly over their smooth expanse, would eliminate a greater part of the nervousness, distraction, and strain of modern metropolitan life.”[*] Within a few decades, statements such as these would

bring both smiles and tears to many people as they inhaled the fumes, listened to the noise, and sat in the congestion of the automobile culture.

Science fiction saw this coming, and it also warned against the potential dangers of the assembly line—a means of production pioneered by Henry Ford and the automobile industry in general. SF writers were among the first to be concerned with the dehumanization that accompanied a system in which the human body had to adapt to the pace of the machine, and whose seemingly inevitable result would be the inability of a person to identify with the products he/she had helped to create.

The mass production made possible by the assembly line led inevitably to mass consumption, and Frederik Pohl and a host of others were to build careers in science fiction by extrapolating the production-consumption process to its logical (and sometimes illogical) conclusion. This was especially true of the growth of the advertising industry, which paralleled the development of mass production techniques (which themselves demanded ever higher levels of consumption) and the consequent requirement to create wants as well as needs. The automobile industry responded by regularly changing its models in a largely successful attempt to create owner dissatisfaction, a practice beautifully extrapolated to human beings in John Jakes’s “The Sellers of the Dream.” The practice of selling products on the installment plan was also pioneered by the auto industry and attacked by science-fiction writers.

The ownership of an automobile quickly became one of the cornerstones of “the American Dream,” for the mobility and status conferred by the car were eagerly sought by people from every class and circumstance. In an age increasingly characterized by loss of identity, the automobile provided an escape into individuality—at least in the mind, if not the heart. Indeed, the car became a major feature of American popular culture, and the experience of growing up often involved the rite of passage of first passing a driver’s test and then actually owning a car. By the fifties and sixties, people could conduct a goodly portion of their lives from their cars—they could withdraw money from a bank, go to a “restaurant,” and watch a movie—all without leaving the driver’s seat. And what a seat it was, for it bestowed on the occupier a feeling of freedom and control that was hard to equal elsewhere—that’s what being in the driver’s seat really meant. But was (and is) it really freedom, or is it a habit, a trap, and a dependency?

For one group of Americans, our adolescents, it remains something very special, for besides the coming-of-age function it performs, it is also a large part of their (and our) culture. The mystique of the back seat and all that incredible image evokes, the popular songs, the admonition to “keep on truckin’,” and (at least when your editors were growing up) the cult of the “hot rod” all hold a special meaning for nearly everyone under thirty. Indeed, the car gave us freedom (at least for a while) from the control and dictates of our own parents. For other age groups, the transition from sedan to sports car and the mystique of the open road, in general, still have great appeal and power.

The effect of the automobile on the United States has been profound, and by no means entirely negative. Perhaps the most damaging aspect of the car culture is that it has prevented the idea of mass transportation from really taking hold in this country. Among its other effects both pro and con are the following:

—The automobile made the rise of the suburb possible, creating a hybrid between rural and urban living.

—It affected social relations and the very nature of the institution of marriage by changing the role of “the woman of the house” from producer (of clothing and other items) to consumer of manufactured goods. The automobile also allowed her to extend her range of contacts far beyond the home for the first time in American history.

—The highway system that the mass ownership of cars required led to a tremendous growth in the tourist industry, and in urban areas, the splitting up of neighborhoods—indeed, “the other side of the tracks” now means the other side of the freeway.

>—The automobile changed the shopping habits of millions because it led to the development of the shopping center . . . a form of “drive-in”.

—that along with the suburbs themselves, killed off the downtown districts of many American cities.

—The materials needed to power and manufacture the automobile meant that whole new industries had to be created, as in the case of petroleum, or else greatly expanded, as in the case of rubber and glass.

And what of the future? The science-fiction stories you are about to read are concerned with what the effect of the automobile could have been, and one or two even wax nostalgic for what it was. For the age of automobiles appears to be nearing an end. The United States, with something like six percent of the world’s population, accounts for over fifty percent of the world’s motor vehicles, but neither the percentage or the total number is rising any more, as oil becomes harder to acquire and more expensive to buy if it is available. Science fiction, in its (thank God) scattergun fashion, predicted some of the most important technological developments and social movements in the history of the world, but very few stories exist that really speak to the social effects of changing over from one form of transportation to another or from one form of fuel to another, as now seems inevitable.

Still, the struggle of humankind to find a way to live with its creations is, from one perspective at least, what science fiction is all about, and the stories in this collection show us the tension, accommodation, love, and conflict that characterize the relationship between humans and machines.

[*] Thomas Conyngton, “Motor Carriages and Street Paving,” Scientific American Supplement, 48:19660 (July 1, 1899); quoted in James J. Flink, The Car Culture (Cambridge, Mass.: The MIT Press, 1975), p. 39. The Flink book is an excellent survey of the impact of the automobile on American life.

DEVIL CAR

By Roger Zelazny

The automobile represents the good life, but it is also a destroyer of life. In the wrong hands it can be a terrible instrument of destruction. But what about when it’s on its own? Television shows from My Mother the Car to the movie Duel (written by Richard Matheson, one of our own) show the wide variety of behavior of the car possessed.

Here, Roger Zelazny gives us yet another version and another vision on this theme.

Murdock sped across the Great Western Road Plain.

High above him the sun was a fiery yo-yo as he took the innumerable hillocks and rises of the Plain at better than a hundred sixty miles an hour. He did not slow for anything, and Jenny’s hidden eyes spotted all the rocks and potholes before they came to them, and she carefully adjusted their course, sometimes without his even detecting the subtle movements of the steering column beneath his hands.

Even through the dark-tinted windshield and the thick goggles he wore, the glare from the fused Plain burnt into his eyes, so that at times it seemed as if he were steering a very fast boat through night, beneath a brilliant alien moon, and that he was cutting his way across a lake of silver fire. Tall dust waves rose in his wake, hung in the air, and after a time settled once more.

“You are wearing yourself out,” said the radio, “sitting there clutching the wheel that way, squinting ahead. Why don’t you try to get some rest? Let me fog the shields. Go to sleep and leave the driving to me.”

“No,” he said. “I want it this way.”

“All right,” said Jenny. “I just thought I would ask.”

“Thanks.”

About a minute later the radio began playing—it was a soft, stringy sort of music.

“Cut that out!”

“Sorry, boss. Thought it might relax you.”

“When I need relaxing, I’ll tell you!”

“Check, Sam. Sorry.”

The silence seemed oppressive after its brief interruption. She was a good car though, Murdock knew that. She was always concerned with his welfare, and she was anxious to get on with his quest.

She was made to look like a carefree Swinger sedan: bright red, gaudy, f

ast. But there were rockets under the bulges of her hood, and two fifty-caliber muzzles lurked just out of sight in the recesses beneath her headlamps; she wore a belt of five- and ten-second timed grenades across her belly; and in her trunk was a spray-tank containing a highly volatile naphthalic.

. . . For his Jenny was a specially designed deathcar, built for him by the Archengineer of the Geeyem Dynasty, far to the East, and all the cunning of that great artificer had gone into her construction.

“We’ll find it this time, Jenny,” he said, “and I didn’t mean to snap at you like I did.”

“That’s all right, Sam,” said the delicate voice, “I am programmed to understand you.”

They roared on across the Great Plain and the sun fell away to the west. All night and all day they had searched, and Murdock was tired. The last Fuel Stop/Rest Stop Fortress seemed so long ago, so far back . . .

Murdock leaned forward and his eyes closed.

The windows slowly darkened into complete opacity. The seat belt crept higher and drew him back away from the wheel. Then the seat gradually leaned backwards until he was reclining on a level plane. The heater came on as the night approached, later.

The seat shook him awake a little before five in the morning.

“Wake up, Sam! Wake up!”

“What is it?” he mumbled.

“I picked up a broadcast twenty minutes ago. There was a recent car-raid out this way. I changed course immediately, and we are almost there.”

“Why didn’t you get me up right away?”

“You needed the sleep, and there was nothing you could do but get tense and nervous.”

“Okay, you’re probably right. Tell me about the raid.”

“Six vehicles, proceeding westward, were apparently ambushed by an undetermined number of wild cars sometime last night. The Patrol Copter was reporting it from above the scene and I listened in. All the vehicles were stripped and drained and their brains were smashed, and their passengers were all apparently killed too. There were no signs of movement.”