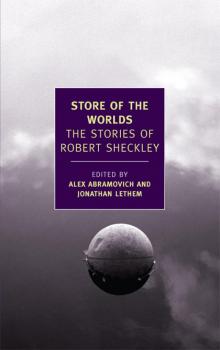

Store of the Worlds: The Stories of Robert Sheckley

Robert Sheckley

ROBERT SHECKLEY (1928–2005) was born in New York City and raised in Maplewood, New Jersey. He joined the army shortly after high school and served in Korea from 1946 to 1948. Returning to New York, Sheckley completed a BA degree at New York University and later took a job in an aircraft factory, leaving as soon as he was able to support himself by selling short stories. In the 1950s and ’60s his stories appeared regularly in science-fiction magazines, especially Galaxy, as well as in Playboy and Esquire. In addition to the science fiction for which he is best known, Sheckley also wrote suspense and mystery stories and television screenplays; from 1979 to 1982 he was the fiction editor of Omni magazine. Sheckley traveled widely, settling for stretches of time in Greenwich Village, Ibiza, London, and Portland, Oregon. Many of Sheckley’s more than fifteen novels and roughly four hundred short stories have been translated and four have been adapted for film. In 2001 he was named Author Emeritus by the Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers of America.

ALEX ABRAMOVICH has been an editor of Feed, Flavorpill, and Very Short List and a writer for The New York Times, The London Review of Books, and other publications. He lives in Oakland, California, and Astoria, Queens.

JONATHAN LETHEM is the author of eight novels, including Girl in Landscape and Chronic City, and five collections of stories and essays, including The Ecstasy of Influence (2011). He has previously written the introductions for the NYRB Classics editions of A Meaningful Life by L.J. Davis and On the Yard by Malcolm Braly. He teaches at Pomona College and lives in Los Angeles and Maine.

STORE OF THE WORLDS

The Stories of

ROBERT SHECKLEY

Edited and with an introduction by

ALEX ABRAMOVICH and

JONATHAN LETHEM

NEW YORK REVIEW BOOKS

New York

CONTENTS

Biographical Notes

Title

Introduction

STORE OF THE WORLDS

The Monsters

Seventh Victim

Shape

Specialist

Warm

Watchbird

The Accountant

Paradise II

All the Things You Are

Protection

The Native Problem

Pilgrimage to Earth

A Wind Is Rising

Dawn Invader

Double Indemnity

Holdout

The Language of Love

Morning After

If the Red Slayer

The Store of the Worlds

Shall We Have a Little Talk?

Cordle to Onion to Carrot

The People Trap

Can You Feel Anything When I Do This?

Is That What People Do?

Beside Still Waters

First Publication

Copyright and More Information

INTRODUCTION

THE LITERARY annals, in the rare moments they’re kind enough to glance at a few of the millions of stories and novels racing away in the rearview mirror, tend to blur context. This is largely a blessing. In advocating for a forgotten or neglected writer, best simply to raise the curtain and say: This is worth your time. For instance, these stories; Robert Sheckley’s little sculptures in syntax emanate a magnetism that still rewards curiosity. They stand up. You ought to read them. Yet once on board, a reader may wonder: Who wrote this stuff? What makes these stories so completely the way they are, instead of some other way?

Ask about the life of Robert Sheckley, and you’ll find out he came from somewhere and ended up in a few other places; he lived among human beings and loved and hated more than a few; he practiced a difficult trade, with difficulty; he attempted things he wasn’t quite able to do, and mastered some other things not quite worth doing. The personal details are particular, and par for the course. Sheckley also, along the way, wrote more than his share of stories that refuse to go out of your mind once you’ve allowed them to enter. By “refuse to go out of your mind” we mean in the sense of Shirley Jackson’s “The Lottery” or Kurt Vonnegut’s “Harrison Bergeron” or George Saunders’s “Pastoralia” or John Cheever’s “The Swimmer” or Ray Bradbury’s “The Veldt” or Bernard Malamud’s “The Jewbird.” That is to say, specifically in the sense of stories standing outside “the realist tradition,” and which seem to form a tradition of their own, however difficult to define except in words charting this distance from the familiar—“surrealist,” “antirealist,” “fabulist”—and which contain little descriptive power of their own.

Sheckley’s stories operate as irresistible language artifacts, like extended puns or paradoxes: off-kilter, provocative, unsettling even if partly silly. They’re like psychedelic lamps that cast an eerie light in one room where they’re encountered, but then turn out to transform one’s view of all subsequent rooms. These are the kind of stories which, if young or otherwise inattentive at first encounter, you may forget the titles and the author’s name, only to rediscover them in some anthology many years later, with a sense of recognition akin to discovering someone else recounting a dream that you yourself once had.

By “more than his share” we want to suggest that Sheckley wrote not just two or three unforgettable things but eight or nine or possibly twelve; more, even, than some of the above-named authors, though they are famous in a way he is not and will likely never be. Sheckley was unforgettable often enough to inspire memorable arguments about which stories, exactly, are his best. These arguments we found ourselves extending, rather than settling, until this inspired us to settle them in a capacious table of contents, one which also satisfies our growing sense that to read Sheckley was to want to read more Sheckley, and that the stories thrived in one another’s company.

So our curtain’s raised. Yet, though it is impossible not to want to argue that Sheckley’s best rise above it, the context for his efforts is awfully particular. The American science-fiction pulp-digest format at mid-century, when Sheckley began publishing stories there, in magazines like Astounding, Amazing, Infinity, If, The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction, and above all, Galaxy, formed a vibrant and diverse alternate literary reality, one bounded from the realms of literary respectability. Within it, excellence was rewarded; Sheckley, only a decade after his first stories’ appearance, was widely understood as a paragon and exemplar. (In that parallel critical realm, Sheckley was often described as “the best of the Galaxy writers,” to an audience for whom that was real and telling praise—surely an illustration of just how parallel a critical realm can be.) The elegant urbanity of Sheckley’s stories meant he was soon also published in Esquire, Playboy, and elsewhere outside the strict limits of the “SF field,” but there can be no question that the development of his career, and his art, took place inside, not outside, that sphere of activity. Nor that it was mostly—or completely—ignored elsewhere.

This matters not because of some general principle that such boundaries should be broken down (in retrospect, any such sentiments are useless) but because, in 1953, the SF field was something more than a social formation or a loose bundle of tropes; it was a kind of argument conducted in collective-imaginative space about what kinds of fictional responses to the twentieth century, with its velocity of wonders and horrors, were possible, or appropriate. Sheckley’s brilliant stories entered into the thick of this argument and became essential to it. Some of their lasting vitality is traceable to this dynamic, even when that framework is obscured. To those only superficially familiar with the history of American SF, Sheckley may appear to write in lonely skepticism against what are often presented as its technocratic rationa

lism and optimism. That form of skepticism, however, was by the time of Sheckley’s appearance already a valued part of the field. Sheckley’s sardonic outcry, his characteristic tone—satire riding an undertow of despair—extended from the morbid and agonistic strains in earlier SF writers like Theodore Sturgeon, Henry Kuttner, and C.M. Kornbluth. The lineage is what made his work legible in the field, and what allowed it to embolden the SF writers who came after, like Philip K. Dick, Harlan Ellison, and J.G. Ballard.

Sheckley’s stories are anchored in another context, too: the explosion, in the 1950s, of American consumer culture, with its devilish mix of seductive freedoms and injunctions to conformity. As much as the Beats, and the “sick” comedians like Lenny Bruce and Mort Sahl, or other artists then fitfully finding voice in terms that anticipated the countercultural ’60s, Sheckley railed against the cloistering assumptions of his time. And yet, as with John Cheever and Richard Yates, the iconography of ’50s culture—commuter businessmen, suburban housewives, the quicksand enticements of middle-class splendor—were imprinted so deeply in Sheckley’s work that he continued to write from inside them, and against them, long after the historical moment had passed.

Our selection of Sheckley’s representative best centers in the 1950s, with just a scattering of stories from subsequent decades. Like the painter Giorgio de Chirico, Sheckley had a period of greatness defined specifically by the application of a formal pressure against the chaos of an instinctive surrealism. In Sheckley’s case, the forms were the motifs of ’50s science fiction: the tales of first contact with aliens; the meticulous exposés of alienation and spectatorship in a burgeoning media culture; the Twilight Zone–style allegories and inversions employed to destabilize the apparent normality of waking life. When in his later stories Sheckley was driven to shake off these generic materials, the results, while often verbally astonishing, suffer from the loss of the structural elegance that makes the earlier work perfect stories of their type.

In an introduction to a gathering of his “greatest hits” that was published in 1979 (one with plenty of overlap with our own selection), Sheckley wrote:

From this position, these stories from a vanished age appear to me safe; acceptable; commodities sanctioned by their own continued existence, and given a mysterious and no doubt spurious air of rightness by the processes of time. Yet when I wrote them, each story involved me in a dangerous movement into an unfamiliar situation, and each story initiated a process in which a concept, itself sometimes barely visible, was to be freighted with words, and perhaps sunk by them.

He added:

I have nothing to say about the stories themselves. To talk about them I would have to reread them, and I went through entirely enough hell writing them ever to want to look at them again. Anyhow, a glance at the contents page brings them all back to me, as well as the dingy rooms in crumbling brownstones in New York where I wrote most of them ...

That’s the sound of Robert Sheckley, morose comedian, raining on his own parade. We wish he could be around to rain on this one.

—ALEX ABRAMOVICH and JONATHAN LETHEM

STORE OF THE WORLDS

THE MONSTERS

CORDOVIR and Hum stood on the rocky mountaintop, watching the new thing happen. Both felt rather good about it. It was undoubtedly the newest thing that had happened for some time.

“By the way the sunlight glints from it,” Hum said, “I’d say it is made of metal.”

“I’ll accept that,” Cordovir said. “But what holds it up in the air?”

They both stared intently down to the valley where the new thing was happening. A pointed object was hovering over the ground. From one end of it poured a substance resembling fire.

“It’s balancing on the fire,” Hum said. “That should be apparent even to your old eyes.”

Cordovir lifted himself higher on his thick tail, to get a better look. The object settled to the ground and the fire stopped.

“Shall we go down and have a closer look?” Hum asked.

“All right. I think we have time—wait! What day is this?”

Hum calculated silently, then said, “The fifth day of Luggat.”

“Damn” Cordovir said. “I have to go home and kill my wife.”

“It’s a few hours before sunset,” Hum said. “I think you have time to do both.”

Cordovir wasn’t sure. “I’d hate to be late.”

“Well then. You know how fast I am,” Hum said. “If it gets late, I’ll hurry back and kill her myself. How about that?”

“That’s very decent of you.” Cordovir thanked the younger man and together they slithered down the steep mountainside.

In front of the metal object both men halted and stood up on their tails.

“Rather bigger than I thought,” Cordovir said, measuring the metal object with his eye. He estimated that it was slightly longer than their village, and almost half as wide. They crawled a circle around it, observing that the metal was tooled, presumably by human tentacles.

In the distance the smaller sun had set.

“I think we had better get back,” Cordovir said, noting the cessation of light complacently.

“I still have plenty of time.” Hum flexed his muscles.

“Yes, but a man likes to kill his own wife.”

“As you wish.” They started off to the village at a brisk pace.

In his house, Cordovir’s wife was finishing supper. She had her back to the door, as etiquette required. Cordovir killed her with a single flying slash of his tail, dragged her body outside, and sat down to eat.

After meal and meditation he went to the Gathering. Hum, with the impatience of youth, was already there, telling of the metal object. He probably bolted his supper, Cordovir thought with mild distaste. After the youngster had finished, Cordovir gave his own observations. The only thing he added to Hum’s account was an idea: that the metal object might contain intelligent beings.

“What makes you think so?” Mishill, another elder, asked.

“The fact that there was fire from the object as it came down,” Cordovir said, “joined to the fact that the fire stopped after the object was on the ground. Some being, I contend, was responsible for turning it off.”

“Not necessarily,” Mishill said. The village men talked about it late into the night. Then they broke up the meeting, buried the various murdered wives, and went to their homes.

Lying in the darkness, Cordovir discovered that he hadn’t made up his mind as yet about the new thing. Presuming it contained intelligent beings, would they be moral? Would they have a sense of right and wrong? Cordovir doubted it, and went to sleep.

The next morning every male in the village went to the metal object. This was proper, since the functions of males were to examine new things and to limit the female population. They formed a circle around it, speculating on what might be inside.

“I believe they will be human beings,” Hum’s elder brother Esktel said. Cordovir shook his entire body in disagreement.

“Monsters, more likely,” he said. “If you take in account—”

“Not necessarily,” Esktel said. “Consider the logic of our physical development. A single focusing eye—”

“But in the great Outside,” Cordovir said, “there may be many strange races, most of them nonhuman. In the infinitude—”

“Still,” Esktel put in, “the logic of our—”

“As I was saying,” Cordovir went on, “the chance is infinitesimal that they would resemble us. Their vehicle, for example. Would we build—”

“But on strictly logical grounds,” Esktel said, “you can see—”

That was the third time Cordovir had been interrupted. With a single movement of his tail he smashed Esktel against the metal object. Esktel fell to the ground, dead.

“I have often considered my brother a boor,” Hum said. “What were you saying?”

But Cordovir was interrupted again. A piece of metal set in the greater piece of metal squeaked, t

urned, and lifted, and a creature came out.

Cordovir saw at once that he had been right. The thing that crawled out of the hole was twin-tailed. It was covered to its top with something partially metal and partially hide. And its color! Cordovir shuddered.

The thing was the color of wet, flayed flesh.

All the villagers had backed away, waiting to see what the thing would do. At first it didn’t do anything. It stood on the metal surface, and a bulbous object that topped its body moved from side to side. But there were no accompanying body movements to give the gesture meaning. Finally, the thing raised both tentacles and made noises.

“Do you think it’s trying to communicate?” Mishill asked softly.

Three more creatures appeared in the metal hole, carrying metal sticks in their tentacles. The things made noises at each other.

“They are decidedly not human,” Cordovir said firmly. “The next question is, are they moral beings?” One of the things crawled down the metal side and stood on the ground. The rest pointed their metal sticks at the ground. It seemed to be some sort of religious ceremony.

“Could anything so hideous be moral?” Cordovir asked, his hide twitching with distaste. Upon closer inspection, the creatures were more horrible than could be dreamed. The bulbous object on their bodies just might be a head, Cordovir decided, even though it was unlike any head he had ever seen. But in the middle of that head instead of a smooth, characterful surface was a raised ridge. Two round indentures were on either side of it, and two more knobs on either side of that. And in the lower half of the head—if such it was —a pale, reddish slash ran across. Cordovir supposed this might be considered a mouth, with some stretching of the imagination.

Nor was this all, Cordovir observed. The things were so constructed as to show the presence of bone! When they moved their limbs, it wasn’t a smooth, flowing gesture, the fluid motion of human beings. Rather, it was the jerky snap of a tree limb.