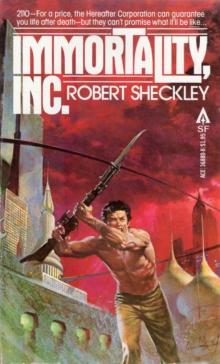

Immortality, Inc

Robert Sheckley

Immortality, Inc

Robert Sheckley

Immortality, Inc. is a 1958 science fiction novella by Robert Sheckley, about a fictional process whereby a human's consciousness may be transferred into a brain-dead body. The serialised form (published under the title Time Killer in Galaxy Science Fiction in 1958-1959) was nominated for the Hugo Award for Best Novel.

Originally published in shorter form as Immortality, Delivered in 1958. It was filmed in 1992 as Freejack, starring Emilio Estevez, Mick Jagger, Rene Russo, and Anthony Hopkins.

IMMORTALITY, INC

by Robert Sheckley

PART ONE

1

Afterwards, Thomas Blaine thought about the manner of his dying and wished it had been more interesting. Why couldn't his death have come while he was battling a typhoon, meeting a tiger's charge, or climbing a windswept mountain? Why had his death been so tame, so commonplace, so ordinary?

But an enterprising death, he realized, would have been out of character for him. Undoubtedly he was meant to die in just the quick, common, messy, painless way he did. And all his life must have gone into the forming and shaping of that death — a vague indication in childhood, a fair promise in his college years, an implacable certainty at the age of thirty-two.

Still, no matter how commonplace, one's death is the most interesting event of one's life. Blaine thought about his with intense curiosity. He had to know about those minutes, those last precious seconds when his own particular death lay waiting for him on a dark New Jersey highway. Had there been some warning sign, some portent? What had he done, or not done? What had he been thinking? Those final seconds were crucial to him. How, exactly, had he died?

He had been driving over a straight, empty white highway, his headlights probing ahead, the darkness receding endlessly before him. His speedometer read seventy-five. It felt like forty. Far down the road he saw headlights coming toward him, the first in hours.

Blaine was returning to New York after a week's vacation at his cabin on Chesapeake Bay. He had fished and swum and dozed in the sun on the rough planks of his dock. One day he sailed his sloop to Oxford and attended a dance at the yacht club that night. He met a silly, pert-nosed girl in a blue dress who told him he looked like a South Seas adventurer, so tanned and tall in his khakis. He sailed back to his cabin the next day, to doze in the sun and dream of giving up everything, loading his sailboat with canned goods and heading for Tahiti. Ah Raiatea, the mountains of Morrea, the fresh trade wind …

But a continent and an ocean lay between him and Tahiti, and other obstacles besides. The thought was only for an hour's dreaming, and definitely not to be acted upon. Now he was returning to New York, to his job as a junior yacht designer for the famous old firm of Mattison & Peters.

The other car's headlights were drawing near. Blaine slowed to sixty.

In spite of his title, there were few yachts for Blaine to design. Old Tom Mattison took care of the conventional cruising boats. His brother Rolf, known as the Wizard of Mystic, had an international reputation for his ocean-racing sailboats and fast one-designs. So what was there for a junior yacht designer to do?

Blaine drew layouts and deck plans, and handled promotion, advertising and publicity. It was responsible work, and not without its satisfactions. But it was not yacht designing.

He knew he should strike out on his own. But there were so many yacht designers, so few customers. As he had told Laura, it was rather like designing arbalests, scorpions and catapults. Interesting creative work, but who would buy your products? “You could find a market for your sailboats,” she had told him, distressingly direct. “Why not make the plunge?”

He had grinned boyishly, charmingly. “Action isn't my forte. I'm an expert on contemplation and mild regret.”

“You mean you’re lazy.”

“Not at all. That's like saying that a hawk doesn't gallop well, or a horse has poor soaring ability. You can't compare different species. I'm just not the go-getter type of human. For me, dreams, reveries, visions, and plans are meant only for contemplation, never for execution.”

“I hate to hear you talk like that,” she said with a sigh.

He had been laying it on a bit thick, of course. But there was a lot of truth in it. He had a pleasant job, an adequate salary, a secure position. He had an apartment in Greenwich Village, a hi-fi, a car, a small cabin on Chesapeake Bay, a fine sloop, and the affection of Laura and several other girls. Perhaps, as Laura somewhat tritely expressed it, he was caught in an eddy on the current of life… But so what? You could observe the scenery better from a gently revolving eddy.

The other car's headlights were very near.

Blaine noticed, with a sense of shock, that he had increased speed to eighty miles an hour.

He let up on the accelerator. His car swerved freakishly, violently, toward the oncoming headlights.

Blowout? Steering failure? He twisted hard on the steering wheel. It wouldn't turn. His car struck the low concrete separation between north and south lanes, and bounded high into the air. The steering wheel came free and spun in his hands, and the engine wailed like a lost soul.

The other car was trying to swerve, too late. They were going to meet nearly head-on.

And Blaine thought, yes, I'm one of them. I'm one of those silly bastards you read about whose cars go out of control and kill innocent people. Christ! Modern cars and modern roads and higher speeds and the same old sloppy reflexes…

Suddenly, unaccountably, the steering wheel was working again, a razor's edge reprieve. Blaine ignored it. As the other car's headlights glared across his windshield, his mood suddenly changed from regret to exultance. For a moment he welcomed the smash, lusted for it, and for pain, destruction, cruelty and death.

Then the cars came together. The feeling of exultance faded as quickly as it had come. Blaine felt a profound regret for all he had left undone, the waters unsailed, movies unseen, books unread, girls untouched— He was thrown forward. The steering wheel broke off in his hands. The steering column speared him through the chest and broke his spine as his head drove through the thick safety glass.

At that instant he knew he was dying.

An instant later he was quickly, commonly, messily, painlessly dead.

2

He awoke in a white bed in a white room.

“He's alive now,” someone said.

Blaine opened his eyes. Two men in white were standing over him. They seemed to be doctors. One was a small, bearded old man. The other was an ugly red-faced man in his fifties.

“What's your name?” the old man snapped

“Thomas Blaine.”

“Age?”

“Thirty-two. But —”

“Marital status?”

“Single. What —”

“Do you see?” the old man said, turning to his red-faced colleague. “Sane, perfectly sane.”

“I would never have believed it,” said the red-faced man.

“But of course. The death trauma has been overrated. Grossly overrated, as my forthcoming book will prove.”

“Hmm. But rebirth depression —”

“Nonsense,” the old man said decisively. “Blaine, do you feel all right?”

“Yes. But I'd like to know —”

“Do you see?” the old doctor said triumphantly. “Alive again and sane. Now will you co-sign the report?”

“I suppose I have no choice,” the red-faced man said. Both doctors left.

Blaine watched them go, wondering what they-had been talking about. A fat and motherly nurse came to his bedside. “How do you feel?” she asked.

“Fine,” Blaine said. “But I'd like to know —”

“Sorry,” the nurse said, “No questions yet,

doctor's orders. Drink this, it'll pep you up. That's a good boy. Don't worry, everything's going to be all right.”

She left. Her reassuring words frightened him. What did she mean, everything's going to be all right? That meant something was wrong! What was it, what was wrong? What was he doing here, what had happened?

The bearded doctor returned, accompanied by a young woman.

“Is he all right, doctor?” the young woman asked.

“Perfectly sane,” the old doctor said. “I'd call it a good splice.”

“Then I can begin the interview?”

“Certainly. Though I cannot guarantee his behavior. The death trauma, though grossly overrated, is still capable of —”

“Yes, fine.” The girl walked over to Blaine and bent over him. She was a very pretty girl, Blaine noticed. Her features were clean-cut, her skin fresh and glowing. She had long, gleaming brown hair pulled too tightly back over her small ears, and there was a faint hint of perfume about her. She should have been beautiful; but she was marred by the immobility of her features, the controlled tenseness of her slender body. It was hard to imagine her laughing or crying. It was impossible to imagine her in bed. There was something of the fanatic about her, of the dedicated revolutionary; but he suspected that her cause was herself.

“Hello, Mr. Blaine,” she said. “I'm Marie Thorne.”

“Hello,” Blaine said cheerfully.

“Mr. Blaine,” she said, “where do you suppose you are?”

“Looks like a hospital. I suppose —” He stopped. He had just noticed a small microphone in her hand.

“Yes, what do you suppose?”

She made a small gesture. Men came forward and wheeled heavy equipment around his bed.

“Go right ahead,” Marie Thorne said. “Tell us what you suppose.”

“To hell with that,” Blaine said moodily, watching the men set up their machines around him. “What is this? What is going on?”

“We’re trying to help you,” Marie Thorne said. “Won't you cooperate?”

Blaine nodded, wishing she would smile. He suddenly felt very unsure of himself. Had something happened to him?

“Do you remember the accident?” she asked.

“What accident?”

“Do you remember being hurt?”

Blaine shuddered as his memory returned in a rush of spinning lights, wailing engine, impact and breakage.

“Yes. The steering wheel broke. I got it through the chest. Then my head hit.”

“Look at your chest,” she said softly.

Blaine looked. His chest, beneath white pajamas, was unmarked.

“Impossible!” he cried. His own voice sounded hollow, distant, unreal. He was aware of the men around his bed talking as they bent over their machines, but they seemed like shadows, flat and without substance. Their thin, unimportant voices were like flies buzzing against a window.

“Nice first reaction.”

“Very nice indeed.”

Marie Thorne said to him, “You are unhurt.”

Blaine looked at his undamaged body and remembered the accident. “I can't believe it!” he cried.

“He's coming on perfectly.”

“Fine mixture of belief and incredulity.”

Marie Thorne said, “Quiet, please. Go ahead, Mr. Blaine.

“I remember the accident,” Blaine said. “I remember the smashing, I remember — dying.”

“Get that?”

“Hell, yes. It really plays!”

“Perfectly spontaneous scene.”

“Marvellous! They'll go wild over it!”

She said, “A little less noise, please. Mr. Blaine, do you remember dying?”

“Yes, yes, I died!”

“His face!”

“That ludicrous expression heightens the reality.”

“I just hope Reilly thinks so.”

She said, “Look carefully at your body, Mr. Blaine. Here's a mirror. Look at your face.”

Blaine looked, and shivered like a man in fever. He touched the mirror, then ran shaking fingers over his face.

“It isn't my face! Where's my face? Where did you put my body and face?”

He was in a nightmare from which he could never awaken. The flat shadow men surrounded him, their voices buzzing like flies against a window, tending their cardboard machines, filled with vague menace, yet strangely indifferent, almost unaware of him. Marie Thorne bent low over him with her pretty, blank face, and from her small red mouth came gentle nightmare words.

“Your body is dead, Mr. Blaine, killed in an automobile accident. You can remember its dying. But we managed to save that part of you that really counts. We saved your mind, Mr. Blaine, and have given you a new body for it.”

Blaine opened his mouth to scream, and closed it again. “It's unbelievable,” he said quietly.

And the flies buzzed.

“Understatement.”

“Well, of course. One can't be frenetic forever.”

“I expected a little more scenery-chewing.”

“Wrongly. Understatement rather accentuates his dilemma.”

“Perhaps, in pure stage terms. But consider the thing realistically. This poor bastard has just discovered that he died in an automobile accident and is now reborn in a new body. So what does he say about it? He says, ‘It's unbelievable.’ Damn it, he's not really reacting to the shock!”

“He is! You’re projecting!”

“Please!” Marie Thorne said. “Go on, Mr. Blaine.”

Blaine, deep in his nightmare, was hardly aware of the soft, buzzing voices. He asked, “Did I really die?”

She nodded.

“And I am really born again in a different body?”

She nodded again, waiting. Blaine looked at her, and at the shadow men tending their cardboard machines. Why were they bothering him? Why couldn't they go pick on some other dead man? Corpses shouldn't be forced to answer questions. Death was man's ancient privilege, his immemorial pact with life, granted to the slave as well as the noble. Death was man's solace, and his right. But perhaps they had revoked that right; and now you couldn't evade your responsibilities simply by being dead.

They were waiting for him to speak. And Blaine wondered if insanity still retained its hereditary privileges. With ease he could slip over and find out.

But insanity is not granted to everyone. Blaine's self-control returned. He looked up at Marie Thorne.

“My feelings,” he said slowly, “are difficult to describe. I've died, and now I'm contemplating the fact. I don't suppose any man fully believes in his own death. Deep down he feels immortal. Death seems to await others, but never oneself. It's almost as though — ”

“Let's cut it right here. He's getting analytical,”

“I think you’re right,” Marie Thorne said. “Thank you very much, Mr. Blaine.”

The men, solid and mundane now, their vague menace disappeared, began rolling their equipment.

“Wait —” Blaine said.

“Don't worry,” she told him. “We'll get the rest of your reactions later. We just wanted to record the spontaneous part now.”

“Damn good while it lasted.”

“A collector's item.”

“Wait!” Blaine cried. “I don't understand. Where am I? What happened? How —”

Marie Thorne said. ”I'm terribly sorry, I must hurry now and edit this for Mr. Reilly.“

The men and equipment were gone. Marie Thorne smiled reassuringly, and hurried away.

Blaine felt ridiculously close to tears. He blinked rapidly when the fat and motherly nurse came back.

“Drink this,” said the nurse. “It'll make you sleep. That's it, take it all down like a good boy. Just relax, you had a big day, what with dying and being reborn and all.”

Two big tears rolled down Blaine's cheeks.

“Dear me,” said the nurse, “the cameras should be here now. Those are genuine spontaneous tears if I ever saw any. Many a tragic and spontaneous

scene I've witnessed in this infirmary, believe me, and I could tell those snooty recording boys something about genuine emotion if I wanted to, and they thinking they know all the secrets of the human heart.”

“Where am I?” Blaine asked drowsily. “Where is this?”

“You'd call it being in the future,” the nurse said.

“Oh,” said Blaine.

Then he was asleep.

3

After many hours he awoke, calm and rested. He looked at the white bed and white room, and remembered.

He had been killed in an accident and reborn in the future. There had been a doctor who considered the death trauma overrated, and men who recorded his spontaneous reactions and declared them a collector's item, and a pretty girl whose features showed a lamentable lack of emotion.

Blaine yawned and stretched. Dead. Dead at thirty-two. A pity, he thought, that this young life was snuffed in its prime. Blaine was a good sort, really, and quite promising…

He was annoyed at his flippant attitude. It was no way to react. He tried to recapture the shock he felt he should feel.

Yesterday, he told himself firmly, I was a yacht designer driving back from Maryland. Today I am a man reborn into the future. The future! Reborn!

No use, the words lacked impact. He had already grown used to the idea. One grows used to anything, he thought, even to one's death. Especially to one's death. You could probably chop off a man's head three times a day for twenty years and he'd grow used to it, and cry like a baby if you stopped…

He didn't care to pursue that train of thought any further.

He thought about Laura. Would she weep for him? Would she get drunk? Or would she just feel depressed at the news, and take a tranquillizer for it? What about Jane and Miriam? Would they even hear about his death? Probably not. Months later they might wonder why he never called any more.

Enough of that. All that was past. Now he was in the future.

But all he had seen of the future was a white bed and a white room, doctors and a nurse, recording men and a pretty girl. So far, it didn't offer much contrast with his own age. But doubtless there were differences.