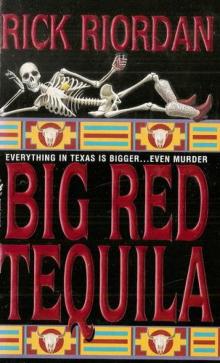

Big Red Tiquila - Rick Riordan

Rick Riordan

Big Red Tiquila

Rick Riordan

1997

Dedication

To Haley Riordan, bienvenido and a good beginning

1

"Who?" said the man occupying my new apartment.

"Tres Navarre," I said.

I pressed the lease agreement against the screen door again so he could see. It was about a hundred degrees on the front porch of the small in-law apartment. The air-conditioning from inside was bleeding through the screen door and evaporating on my face. Somehow that just made it seem hotter.

The man inside my apartment glanced at the paper, then squinted at me like I was some bizarre piece of modern art. Through the metal screen he looked even uglier than he probably was—heavyset, about forty, crew cut, features all pinched toward the center of his face. He was bare-chested and wore the kind of thick polyester gym shorts only P.E. coaches wear. Use small words, I thought.

"I rented this apartment for July fifteenth. You were supposed to move out by then. It’s July twenty-fourth."

No signs of remorse from the coach. He looked back over his shoulder, distracted by a double play on the TV. He looked at me again, now slightly annoyed.

“Look, asshole," he said. "I told Gary I needed a few extra weeks. My transfer hasn’t come through yet, okay? Maybe August you can have it."

We stared at each other. In the pecan tree next to the steps a few thousand cicadas decided to start their metallic chirping. I looked back at the cabby who was still waiting at the curb, happily reading his TV Guide while the meter ran. Then I turned back to the coach and smiled-friendly, diplomatic.

"Well," I said, "I tell you what. I’ve got the moving van coming here tomorrow from California. That means you’ve got to be out of here today. Since you’ve had a free week on my tab already, I figure I can give you an extra hour or so. I’m going to get my bags out of the cab, then when I come back you can let me in and start packing."

If it was possible for his eyes to squint any closer together, they did. "What the fuck—"

I turned my back on him and went out to the cab. I hadn’t brought much with me on the plane-one bag for clothes and one for books, plus Robert Johnson in his carrying cage. I collected my things, asked the cabby to wait, then walked back up the sidewalk. Pecans crunched under my feet. Robert Johnson was silent, still

disoriented from his traumatic flight.

The house didn’t look much better on a second take. Like most of the other sleeping giants on Queen Anne Street, Number 90 had two stories, an ancient green-shingled roof, bare wood siding where the white paint had peeled away, a huge screened-in-front porch sagging under tons of red bougainvillea. The right side of the building, where the in-law’s smaller porch stuck out, had shifted on its foundations and now drooped down and backward, as if that half of the house ad suffered a stroke.

The coach had opened the door for me. In fact he was standing in it now, smiling, holding a baseball bat.

"I said August, asshole," he told me.

I set my bags and Robert Johnson’s cage down on the bottom step. The coach smiled like you might at a dirty joke. One of his front teeth was two different colors.

"You ever try dental picks?" I said.

He developed a few new creases on his forehead.

“What—?"

“Never mind, " I said. "You got moving boxes or you just want to put your stuff in Hefty bags? You strike me as a Hefty-bag man."

“Fuck you."

I smiled and walked up the steps.

The porch was way too narrow to swing a bat, but he did his best to butt me in the chest with it. I moved sideways and stepped in next to him, grabbing his wrist. If you apply pressure correctly, you can use the nei guan point, just above the wrist joint, in place of CPR to stimulate the heart. One of the reasons Chinese grandmothers wear those long pins in their hair, in fact, is to prick the nei guan in case someone in the family has a heart attack. Apply pressure a little harder, and it sends a charge through the nervous system that is pretty unpleasant.

The coach’s face turned red; his pinched features loosened up in shock. The bat clattered down the steps. As he doubled over, clutching his arm, I pushed I through the door.

The TV was still going in the main room—a washed-up Saturday Night Live comedian was guzzling a light beer, surrounded by five or six cheerleaders. Nothing else in the room except a mattress and a pile of clothes in the corner and a tattered easy chair. On the kitchen counter there was a mound of old dishes and fast-food cartons. The smell was somewhere between fried meat and sour wet laundry.

"You’ve done wonders with the place," I said. “I can see why-"

When I turned around the coach was standing behind me and his fist was a few inches from my face, coming in for a landing.

I twisted out of its way and pushed down on his wrist with one hand. With the other hand I slammed up on the elbow, bending the joint the wrong way. I’m sure I didn’t break it, but I’m pretty sure it hurt like hell anyway. The coach fell down on the kitchen floor and I went to check out the bathroom. A toothbrush, one towel, the new Penthouse on the toilet tank. All the comforts of home.

It took about fifteen minutes to find a roll of garbage bags and stuff the coach’s things into them.

"You broke my arm," he told me. He was still sitting on the kitchen floor, with his eyes tightly closed. I unplugged the TV and put it outside.

" Some people like ice for a joint problem like that," I told him, moving out the chair. “I think it’s better if I you use a hot-water bottle. Keep it warm for a while. Two days from now you won’t feel anything."

He told me he’d sue, I think. He told me a lot of things, but I wasn’t listening much anymore. I was tired, it was hot, and I was starting to remember why I’d stayed away from San Antonio for so many years. The coach was in enough pain not to fight much as I tucked him into the cab with most of his stuff and paid the cabby to take him to a motel. Leaving the TV and easy chair in the front yard, I brought my things inside and shut the door behind me.

Robert Johnson slunk out of his cage cautiously when I opened it. His black fur was slicked the wrong way on one side and his yellow eyes were wide. He wobbled slightly getting back his land legs. I knew how he felt. He sniffed the carpet, then looked at me with total disdain.

"Row," he said.

"Welcome home," I said.

2

"Was fixing to evict him one of these days," Gary Hales mumbled.

My new landlord didn’t seem too concerned about my disagreement with the former tenant. Gary Hales didn’t seem too concerned about anything. Gary was an anemic watercolor of a man. His eyes, voice, and mouth were all soft and liquid, his skin a washed-out blue that matched his guayabera shirt. I got the feeling he might just dilute down to nothing if he I got caught in a good rain.

He stared at our finalized lease as if he were trying to remember what it was. Then he read it one more time, his lips moving, his shaky hand following each line with the tip of a black pen. He got stuck on the signature line. He frowned. “Jackson?"

"Legally," I told him. "Tres, as in the Third. Usually I go by that, unless you’re my mother and you’re mad at me, in which case it’s Jackson."

Gary stared at me.

“Or occasionally ‘Asshole,’ " I offered.

Gary’s pale eyes had started to glaze over. I thought I’d probably lost him after "legally," but he surprised me.

"Jackson Navarre," he said slowly. "Like that sheriff that got kilt?"

I took the lease out of Gary’s hand and folded it up. "Yeah," I said. “Like that."

Then the wall started ringing. Gary’s eyes floated over listlessly to

where the sound had come from. I waited for an explanation.

"She axed me for the number here," he said, like he was reminding himself about it. "Told her I’d change the name over to you t’morrow."

He shuffled across the room and pulled a built-in ironing board out from the living—room wall. In the alcove behind it was an old black rotary phone.

I picked it up on the fourth ring and said: “Mother, you’re unbelievable."

She sighed loudly into the receiver, a satisfied kind of sound.

"Just an old beau at Southwestern Bell, honey. Now when are you coming over?"

I thought about it. The prospect wasn’t pleasant after the day I’d had. On the other hand, I needed transportation.

"Maybe this evening. I’ll need to borrow the VW if you’ve still got it. "

“It’s been sitting in my garage for ten years," she said. "You think it’ll run you’re welcome to it. I expect you’ll be visiting Lillian tonight?"

In the background at my mother’s house I heard the sound of a pool cue breaking a setup. Somebody laughed.

"Mother—"

"All right, I didn’t ask. We’ll see you later on, dear."

After Gary had shuffled back over to the main part of the house, I checked my watch. Three o’clock San Francisco time. Even on Saturday afternoon there was still a good chance I could reach Maia Lee at Terrence & Goldman.

No such luck. When her voice mail got through explaining to me what “regular business hours" meant, I left my new number, then held the line for a second longer, thinking about what to say. I could still see Maia’s face the way it looked this morning at five when she dropped me off at SFO—smiling, a sisterly kiss, someone polite whom I didn’t recognize. I hung up the phone.

I found some vinegar and baking soda in the pantry and spent an hour cleaning away the sights and smells of the former tenant from the bathroom while Robert Johnson practiced climbing the shower curtain.

A little before sunset somebody knocked on my door.

“Mother," I grumbled to myself. Then I looked out the window and saw it wasn’t quite that bad—just a couple of uniformed cops leaning against their unit in the driveway, waiting. I opened the front door and saw the second ugliest face I’d seen through my screen door so far today.

"You know," the man croaked, "somebody just handed me this complaint from one Bob Langston of 90 Queen Anne’s Street. Guy’s a G-7 at Fort Sam, no less. Assault, it says. Trespassing, it says. Langston claims some maniac named Navarre tried to karate him to death, for Christ’s sake."

I was surprised how much he’d changed. His cheeks had hollowed out like craters and he’d gone bald to the point where he had to comb a greasy flap of side hair over the top just to keep up appearances. About the only things he had more of were stomach and mustache. The former covered his twenty-pound belt buckle. The latter covered his mouth almost down to his double chins. I remember as a kid wondering how he lit his cigarettes without setting his face on fire.

"Jay Rivas," I said.

Maybe he smiled. There was no way to tell under the whiskers. Somehow he located his lips with a cigarette and took a long drag.

"So you know what I tell the guys?" Rivas asked. "I say no way. No way could I be so lucky as to have Jackson Navarre’s baby boy back in town from San Fag-cisco to bring sunlight into my dreary life. That’s what I tell them."

"It was tai chi chuan, Jay, not karate. Purely defensive."

"What the fuck, kid, " he said, leaning his hand against the door frame. "You just about kimcheed this guy’s arm off. Give me a reason I shouldn’t treat you to some free accommodations at the County Annex tonight. "

I referred him to Gary Hales’s and my lease agreement, then told him about Mr. Langston’s less-than-warm reception. Rivas seemed unimpressed.

Of course, Jay Rivas always seemed unimpressed when it came to my family. He’d worked with my dad in the late seventies on a joint investigation that didn’t go so well. My dad had expressed his displeasure to his friends at SAPD, and here was Detective Rivas twenty years later, following up on low-priority assault cases.

"You made it out here awfully quick, Jay," I said. “Should I be flattered or do they normally send you out for the trivial stuff?"

Rivas blew smoke through his mustache. His double chins turned a beautiful shade of red, like a toad’s.

“Why don’t we go inside and talk about that," he suggested, his voice calm.

He motioned for me to open the screen door. It didn’t happen.

"I’m losing air conditioning, here, Detective," I said. We stared at each other for about two minutes. Then he disappointed me. He backed down the steps. He stuck the cigarette in his mouth and shrugged.

“Okay, kid, " he said. "Just take the hint."

"Which is? "

Then I’m sure he smiled. I could see the cigarette curve up through the whiskers. “You get your nose into anything else, I’ll see you get some nice cellmates downtown."

“You’re a loving human being, Jay."

“To hell with that."

He tossed his cigarette onto Bob Langston’s "God Bless Home" welcome mat and swaggered back to I where the two uniforms were waiting for him. I watched their unit disappear down Queen Anne Street. Then I went inside.

I looked around my new home—the bubbled molding on the ceiling, the gray paint that had started peeling away from the walls. I looked down at Robert Johnson. He was now sitting in my open suitcase and staring at me with an insulted expression. A subtle hint. I called Lillian’s number with the thirst of a man who needs water after a shot of mescal.

It was worth it.

She said: "Tres?" and ripped away the last ten years of my life like so much tissue paper.

"Yeah," I told her. "I’m in my new place. More or less."

She hesitated. "You don’t sound too happy about it."

"It’s nothing. I’ll tell you the story later."

"I can’t wait."

We held the line for a minute—the kind of silence where you lean into the receiver, trying to push yourself through by sheer force.

"I love you," Lillian said. "Is it too soon to say that?"

I swallowed down the ball bearing in my throat.

"How about nine? I’ve got to liberate the VW from my mother’s garage."

Lillian laughed. "The Orange Thing still runs?"

"It’d better. I’ve got a hot date tonight."

"You’d better believe it."

We hung up. I looked over at Robert Johnson, who was still sitting in my suitcase.

"Deal with it," I told him.

I felt like it was 1985 again. I was still nineteen, my dad was alive, and I was still in love with the girl I’d been planning on marrying since junior high. We were going seventy miles an hour down I-35 in an old VW that could only do sixty-five, chasing down god-awful tequila with even more god-awful Big Red cream soda. Teenage champagne.

I changed clothes again and called a cab. I tried to remember the taste of Big Red tequila. I wasn’t sure I could ever drink something like that again and smile, but I was ready to try.

3

Broadway from Queen Anne to my mother’s house was lined with pink taco restaurants. Not the run-down family—owned places I remembered from high school—these were franchises with neon signs and pastel flamingos painted along the walls. There must have been one every half mile.

Landmarks in downtown Alamo Heights had disappeared. The Montanios had sold off the 50-50 Bar, my father’s old watering hole. Sill’s Snack Shack was now a Texaco. Most of the local places like that, named after people I knew, had been swallowed by faceless national chains. Other storefronts were boarded up, their half-hearted "For Lease" signs weathered down to illegibility. The city was still a thousand kinds of green, though. In every block the buildings were crowded by ancient live oak trees, huisaches, and Texas laurels. It was the kind of rich green you see in most towns only right after a big rain.

It

was sunset and still ninety—five degrees when the cab turned down Vandiver. There were none of the soft afternoon colors you get in San Francisco, no hills for shadows, no fog to airbrush the scenery for tourists on the Golden Gate. Here the light was honest—everything it touched was sharply focused, outlined in heat. The sun kept its eye on the city until its very last moment on the horizon, looking at you as if to say: "Tomorrow PM going to kick your ass."

Vandiver Street hadn’t changed. Sprinklers cut circles across the huge lawns, and wraithlike retirees stared aimlessly out the picture windows of their white, post-WW II houses. The only difference was that Mother had reincarnated her house again. If I hadn’t recognized the huge oak tree in front, the dirt yard covered with acorns and patches of wild strawberry, I would have let the cabby drive right past it.

Once I saw it, I was tempted to drive past anyway. It was stucco now—olive-colored walls with a bright red clay tile roof. The last time I’d seen the house it looked more like a log cabin. Before that it had been pseudo-Frank Lloyd Wright. Over the years Mother had become close with several contractors who depended on her for steady income.

"Tres, honey," she said at the door, pulling my face forward with both hands for a kiss.

She hadn’t changed. At fifty-six she could still pass for thirty. She wore a loose Guatemalan dress, fuchsia with blue stitching, and her black hair was tied back with a festive knot of colored ribbons. The smell of vanilla incense wafted out the door with her.

"You look great, Mother." I meant it.

She smiled, dragging me inside by the arm and steering me toward the pool table at the far end of her huge living room.

The decor had shifted from late Bohemian to early Santa Fe, but the general theme was still the same: "put stuff everywhere." Shelves and tables were overloaded with antique knives, papier-maché dolls, carved wooden boxes, replica coyotes howling at replica moons, a neon cactus, anything to attract the eye.

Around the pool table were three old acquaintances from high school. I shook hands with Barry Williams and Tom Cavagnaro. Both had played varsity with me. They were here because my mom loved entertaining guests with pool and free beer. Then I nodded to Jess Makar, who had graduated when I was a freshman. jess was here because he was dating my mother.