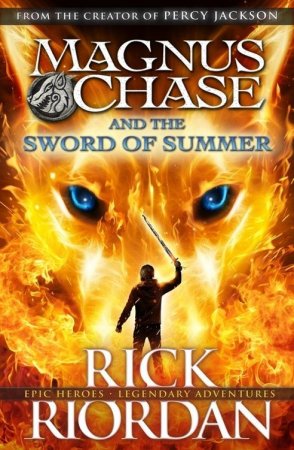

The Sword of Summer

Rick Riordan

To Cassandra Clare

Thanks for letting me share the excellent name Magnus

ONE

Good Morning! You’re Going to Die

Yeah, I know. You guys are going to read about how I died in agony, and you’re going be like, ‘Wow! That sounds cool, Magnus! Can I die in agony, too?’

No. Just no.

Don’t go jumping off any rooftops. Don’t run into the highway or set yourself on fire. It doesn’t work that way. You will not end up where I ended up.

Besides, you wouldn’t want to deal with my situation. Unless you’ve got some crazy desire to see undead warriors hacking one another to pieces, swords flying up giants’ noses and dark elves in snappy outfits, you shouldn’t even think about finding the wolf-headed doors.

My name is Magnus Chase. I’m sixteen years old. This is the story of how my life went downhill after I got myself killed.

My day started out normal enough. I was sleeping on the sidewalk under a bridge in the Public Garden when a guy kicked me awake and said, ‘They’re after you.’

By the way, I’ve been homeless for the past two years.

Some of you may think, Aw, how sad. Others may think, Ha, ha, loser! But, if you saw me on the street, ninety-nine per cent of you would walk right past like I’m invisible. You’d pray, Don’t let him ask me for money. You’d wonder if I’m older than I look, because surely a teenager wouldn’t be wrapped in a stinky old sleeping bag, stuck outside in the middle of a Boston winter. Somebody should help that poor boy!

Then you’d keep walking.

Whatever. I don’t need your sympathy. I’m used to being laughed at. I’m definitely used to being ignored. Let’s move on.

The bum who woke me was a guy called Blitz. As usual, he looked like he’d been running through a dirty hurricane. His wiry black hair was full of paper scraps and twigs. His face was the colour of saddle leather and was flecked with ice. His beard curled in all directions. Snow caked the bottom of his trench coat where it dragged around his feet – Blitz being about five feet five – and his eyes were so dilated the irises were all pupil. His permanently alarmed expression made him look like he might start screaming any second.

I blinked the gunk out of my eyes. My mouth tasted like day-old hamburger. My sleeping bag was warm, and I really didn’t want to get out of it.

‘Who’s after me?’

‘Not sure.’ Blitz rubbed his nose, which had been broken so many times it zigzagged like a lightning bolt. ‘They’re handing out flyers with your name and picture.’

I cursed. Random police and park rangers I could deal with. Truant officers, community-service volunteers, drunken college kids, addicts looking to roll somebody small and weak – all those would’ve been as easy to wake up to as pancakes and orange juice.

But when somebody knew my name and my face – that was bad. That meant they were targeting me specifically. Maybe the folks at the shelter were mad at me for breaking their stereo. (Those Christmas carols had been driving me crazy.) Maybe a security camera had caught that last bit of pickpocketing I did in the Theater District. (Hey, I needed money for pizza.) Or maybe, unlikely as it seemed, the police were still looking for me, wanting to ask questions about my mom’s murder …

I packed my stuff, which took about three seconds. The sleeping bag rolled up tight and fitted in my backpack with my toothbrush and a change of socks and underwear. Except for the clothes on my back, that’s all I owned. With the backpack over my shoulder and the hood of my jacket pulled low, I could blend in with pedestrian traffic pretty well. Boston was full of college kids. Some of them were even more scraggly and younger-looking than me.

I turned to Blitz. ‘Where’d you see these people with the flyers?’

‘Beacon Street. They’re coming this way. Middle-aged white guy and a teenage girl, probably his daughter.’

I frowned. ‘That makes no sense. Who –’

‘I don’t know, kid, but I gotta go.’ Blitz squinted at the sunrise, which was turning the skyscraper windows orange. For reasons I’d never quite understood, Blitz hated the daylight. Maybe he was the world’s shortest, stoutest homeless vampire. ‘You should go see Hearth. He’s hanging out in Copley Square.’

I tried not to feel irritated. The local street people jokingly called Hearth and Blitz my mom and dad because one or the other always seemed to be hovering around me.

‘I appreciate it,’ I said. ‘I’ll be fine.’

Blitz chewed his thumbnail. ‘I dunno, kid. Not today. You gotta be extra careful.’

‘Why?’

He glanced over my shoulder. ‘They’re coming.’

I didn’t see anybody. When I turned back, Blitz was gone.

I hated it when he did that. Just – Poof. The guy was like a ninja. A homeless vampire ninja.

Now I had a choice: go to Copley Square and hang out with Hearth, or head towards Beacon Street and try to spot the people who were looking for me.

Blitz’s description of them made me curious. A middle-aged white guy and a teenage girl searching for me at sunrise on a bitter-cold morning. Why? Who were they?

I crept along the edge of the pond. Almost nobody took the lower trail under the bridge. I could hug the side of the hill and spot anyone approaching on the higher path without them seeing me.

Snow coated the ground. The sky was eye-achingly blue. The bare tree branches looked like they’d been dipped in glass. The wind cut through my layers of clothes, but I didn’t mind the cold. My mom used to joke that I was half polar bear.

Dammit, Magnus, I chided myself.

After two years, my memories of her were still a minefield. I’d stumble over one, and instantly my composure would be blown to bits.

I tried to focus.

The man and the girl were coming this way. The man’s sandy hair grew over his collar – not like an intentional style, but like he couldn’t be bothered to cut it. His baffled expression reminded me of a substitute teacher’s: I know I was hit by a spit wad, but I have no idea where it came from. His smart shoes were totally wrong for a Boston winter. His socks were different shades of brown. His tie looked like it had been tied while he spun around in total darkness.

The girl was definitely his daughter. Her hair was just as thick and wavy, though lighter blonde. She was dressed more sensibly in snow boots, jeans and a parka, with an orange T-shirt peeking out at the neckline. Her expression was more determined, angry. She gripped a sheaf of flyers like they were essays she’d been graded on unfairly.

If she was looking for me, I did not want to be found. She was scary.

I didn’t recognize her or her dad, but something tugged at the back of my skull … like a magnet trying to pull out a very old memory.

Father and daughter stopped where the path forked. They looked around as if just now realizing they were standing in the middle of a deserted park at no-thank-you o’clock in the dead of winter.

‘Unbelievable,’ said the girl. ‘I want to strangle him.’

Assuming she meant me, I hunkered down a little more.

Her dad sighed. ‘We should probably avoid killing him. He is your uncle.’

‘But two years?’ the girl demanded. ‘Dad, how could he not tell us for two years?’

‘I can’t explain Randolph’s actions. I never could, Annabeth.’

I inhaled so sharply that I was afraid they would hear me. A scab was ripped off my brain, exposing raw memories from when I was six years old.

Annabeth. Which meant the sandy-haired man was … Uncle Frederick?

I flashed back to the last family Thanksgiving we’d shared: Annabeth and me hiding in the library at Uncle Randolph’s town house, playing with dominoes while the adults y

elled at each other downstairs.

You’re lucky you live with your momma. Annabeth stacked another domino on her miniature building. It was amazingly good, with columns in front like a temple. I’m going to run away.

I had no doubt she meant it. I was in awe of her confidence.

Then Uncle Frederick appeared in the doorway. His fists were clenched. His grim expression was at odds with the smiling reindeer on his sweater. Annabeth, we’re leaving.

Annabeth looked at me. Her grey eyes were a little too fierce for a first-grader’s. Be safe, Magnus.

With a flick of her finger, she knocked over her domino temple.

That was the last time I’d seen her.

Afterwards, my mom had been adamant: We’re staying away from your uncles. Especially Randolph. I won’t give him what he wants. Ever.

She wouldn’t explain what Randolph wanted, or what she and Frederick and Randolph had argued about.

You have to trust me, Magnus. Being around them … it’s too dangerous.

I trusted my mom. Even after her death, I hadn’t had any contact with my relatives.

Now, suddenly, they were looking for me.

Randolph lived in town, but, as far as I knew, Frederick and Annabeth still lived in Virginia. Yet here they were, passing out flyers with my name and photo on them. Where had they even got a photo of me?

My head buzzed so badly that I missed some of their conversation.

‘– to find Magnus,’ Uncle Frederick was saying. He checked his smartphone. ‘Randolph is at the city shelter in the South End. He says no luck. We should try the youth shelter across the park.’

‘How do we even know Magnus is alive?’ Annabeth asked miserably. ‘Missing for two years? He could be frozen in a ditch somewhere!’

Part of me was tempted to jump out of my hiding place and shout, TA-DA!

Even though it had been ten years since I’d seen Annabeth, I didn’t like seeing her distressed. But after so long on the streets I’d learned the hard way: you never walk into a situation until you understand what’s going on.

‘Randolph is sure Magnus is alive,’ said Uncle Frederick. ‘He’s somewhere in Boston. If his life is truly in danger …’

They set off towards Charles Street, their voices carried away by the wind.

I was shivering now, but it wasn’t from the cold. I wanted to run after Frederick, tackle him and demand to hear what was going on. How did Randolph know I was still in town? Why were they looking for me? How was my life in danger now more than on any other day?

But I didn’t follow them.

I remembered the last thing my mom ever told me. I’d been reluctant to use the fire escape, reluctant to leave her, but she’d gripped my arms and made me look at her. Magnus, run. Hide. Don’t trust anyone. I’ll find you. Whatever you do, don’t go to Randolph for help.

Then, before I’d made it out of the window, the door of our apartment had burst into splinters. Two pairs of glowing blue eyes had emerged from the darkness …

I shook off the memory and watched Uncle Frederick and Annabeth walk away, veering east towards the Common.

Uncle Randolph … For some reason, he’d contacted Frederick and Annabeth. He’d got them to Boston. All this time, Frederick and Annabeth hadn’t known that my mom was dead and I was missing. It seemed impossible, but, if it were true, why would Randolph tell them about it now?

Without confronting him directly, I could think of only one way to get answers. His town house was in Back Bay, an easy walk from here. According to Frederick, Randolph wasn’t home. He was somewhere in the South End, looking for me.

Since nothing started a day better than a little breaking and entering, I decided to pay his place a visit.

TWO

The Man with the Metal Bra

The family mansion sucked.

Oh, sure, you wouldn’t think so. You’d see the massive six-storey brownstone with gargoyles on the corners of the roof, stained-glass transom windows, marble front steps and all the other blah, blah, blah, rich-people-live-here details, and you’d wonder why I’m sleeping on the streets.

Two words: Uncle Randolph.

It was his house. As the oldest son, he’d inherited it from my grandparents, who died before I was born. I never knew much about the family soap opera, but there was a lot of bad blood between the three kids: Randolph, Frederick and my mom. After the Great Thanksgiving Schism, we never visited the ancestral homestead again. Our apartment was, like, half a mile away, but Randolph might as well have lived on Mars.

My mom only mentioned him if we happened to be driving past the brownstone. Then she would point it out the way you might point out a dangerous cliff. See? There it is. Avoid it.

After I started living on the streets, I would sometimes walk by at night. I’d peer in the windows and see glowing display cases of antique swords and axes, creepy helmets with face masks staring at me from the walls, statues silhouetted in the upstairs windows like petrified ghosts.

Several times I considered breaking in to poke around, but I’d never been tempted to knock on the door. Please, Uncle Randolph, I know you hated my mother and haven’t seen me in ten years; I know you care more about your rusty old collectibles than you do about your family, but may I live in your fine house and eat your leftover crusts of bread?

No thanks. I’d rather be on the street, eating day-old falafel from the food court.

Still … I figured it would be simple enough to break in, look around and see if I could find answers about what was going on. While I was there, maybe I could grab some stuff to pawn.

Sorry if that offends your sense of right and wrong.

Oh, wait. No, I’m not.

I don’t steal from just anybody. I choose obnoxious jerks who have too much already. If you’re driving a new BMW and you park it in a disabled spot without a permit, then, yeah, I’ve got no problem jimmying your window and taking some change from your cupholder. If you’re coming out of Barneys with your bag of silk handkerchiefs, so busy talking on your phone and pushing people out of your way that you’re not paying attention, I am there for you, ready to pickpocket your wallet. If you can afford five thousand dollars to blow your nose, you can afford to buy me dinner.

I am judge, jury and thief. And, as far as obnoxious jerks went, I figured I couldn’t do better than Uncle Randolph.

The house fronted Commonwealth Avenue. I headed around back to the poetically named Public Alley 429. Randolph’s parking spot was empty. Stairs led down to the basement entrance. If there was a security system, I couldn’t spot it. The door was a simple latch lock without even a deadbolt. Come on, Randolph. At least make it a challenge.

Two minutes later I was inside.

In the kitchen, I helped myself to some sliced turkey, crackers and milk from the carton. No falafel. Dammit. Now I was really in the mood for some, but I found a chocolate bar and stuffed it in my coat pocket for later. (Chocolate must be savoured, not rushed.) Then I headed upstairs into a mausoleum of mahogany furniture, oriental rugs, oil paintings, marble-tiled floors and crystal chandeliers … It was just embarrassing. Who lives like this?

At age six, I couldn’t appreciate how expensive all this stuff was, but my general impression of the mansion was the same: dark, oppressive, creepy. It was hard to imagine my mom growing up here. It was easy to understand why she’d become a fan of the great outdoors.

Our apartment over the Korean BBQ joint in Allston had been cosy enough, but Mom never liked being inside. She always said her real home was the Blue Hills. We used to go hiking and camping there in all kinds of weather – fresh air, no walls or ceilings, no company but the ducks, geese and squirrels.

This brownstone, by comparison, felt like a prison. As I stood alone in the foyer, my skin crawled with invisible beetles.

I climbed to the next floor. The library smelled of lemon polish and leather, just like I remembered. Along one wall was a lit glass case full of Randolph’s rusty Viking helmets and

corroded axe blades. My mom once told me that Randolph taught history at Harvard before some big disgrace got him fired. She wouldn’t go into details, but clearly the guy was still an artefact nut.

You’re smarter than either of your uncles, Magnus, my mom once told me. With your grades, you could easily get into Harvard.

That had been back when she was still alive, I was still in school, and I might have had a future that extended past finding my next meal.

In one corner of Randolph’s office sat a big slab of rock like a tombstone, the front chiselled and painted with elaborate red swirly designs. In the centre was a crude drawing of a snarling beast – maybe a lion or a wolf.

I shuddered. Let’s not think about wolves.

I approached Randolph’s desk. I’d been hoping for a computer, or a notepad with helpful information – anything to explain why they were looking for me. Instead, spread across the desk were pieces of parchment as thin and yellow as onion skin. They looked like maps a school kid in medieval times had made for social studies: faint sketches of a coastline, various points labelled in an alphabet I didn’t know. Sitting on top of them, like a paperweight, was a leather pouch.

My breath caught. I recognized that pouch. I untied the drawstring and grabbed one of the dominoes … except it wasn’t a domino. My six-year-old self had assumed that’s what Annabeth and I had been playing with. Over the years, the memory had reinforced itself. But, instead of dots, these stones were painted with red symbols.

The one in my hand was shaped like a tree branch or a deformed F:

My heart pounded. I wasn’t sure why. I wondered if coming here had been such a good idea. The walls felt like they were closing in. On the big rock in the corner, the drawing of the beast seemed to sneer at me, its red outline glistening like fresh blood.

I moved to the window. I thought it might help to look outside. Along the centre of the avenue stretched the Commonwealth Mall – a ribbon of parkland covered in snow. The bare trees were strung with white Christmas lights. At the end of the block, inside an iron fence, the bronze statue of Leif Erikson stood on his pedestal, his hand cupped over his eyes. Leif gazed towards the Charlesgate overpass as if to say, Look, I discovered a highway!

My mom and I used to joke about Leif. His armour was on the skimpy side: a short skirt and a breastplate that looked like a Viking bra.

I had no clue why that statue was in the middle of Boston, but I figured it couldn’t be a coincidence that Uncle Randolph grew up to study Vikings. He’d lived here his whole life. He’d probably looked at Leif every day out of the window. Maybe as a child Randolph had thought, Someday, I want to study Vikings. Men who wear metal bras are cool!

My eyes drifted to the base of the statue. Somebody was standing there … looking up at me.

You know how when you see somebody out of context and it takes you a second to recognize them? In Leif Erikson’s shadow stood a tall, pale man in a black leather jacket, black motorcycle pants and pointy-toed boots. His short, spiky hair was so blond it was almost white. His only dash of colour was a striped red-and-white scarf wrapped around his neck and spilling off his shoulders like a melted candy cane.

If I didn’t know him, I might’ve guessed he was cosplaying some anime character. But I did know him. It was Hearth, my fellow homeless dude and surrogate ‘mom’.

I was a little creeped out, a little offended. Had he seen me on the street and followed me? I didn’t need some fairy god-stalker looking after me.

I spread my hands: What are you doing here?

Hearth made a gesture like he was plucking something from his cupped hand and throwing it away. After two years of hanging around him, I was getting pretty good at reading sign language.

He was saying GET OUT.

He didn’t look alarmed, but it was hard to tell with Hearth. He never showed much emotion. Whenever we hung out, he mostly just stared at me with those pale grey eyes like he was waiting for me to explode.

I lost valuable seconds trying to figure out what he meant, why he was here when he was supposed to be in Copley Square.

He gestured again: both hands pointing forward with two fingers, dipping up and down twice. Hurry.