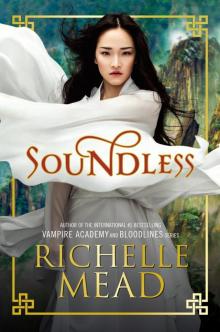

Soundless

Richelle Mead

Penguin.com

Razorbill, an Imprint of Penguin Random House

Copyright © 2015 Penguin Random House LLC

Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader.

ISBN: 978-0-698-14843-7

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, businesses, companies, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

Version_1

Contents

Copyright

Title Page

Dedication

CHAPTER 1

CHAPTER 2

CHAPTER 3

CHAPTER 4

CHAPTER 5

CHAPTER 6

CHAPTER 7

CHAPTER 8

CHAPTER 9

CHAPTER 10

CHAPTER 11

CHAPTER 12

CHAPTER 13

CHAPTER 14

CHAPTER 15

CHAPTER 16

CHAPTER 17

CHAPTER 18

CHAPTER 19

EPILOGUE

Acknowledgments

In memory of my father, who lost his sight but never his vision.

CHAPTER 1

MY SISTER IS IN TROUBLE, and I have only minutes to help her.

She doesn’t see it. She’s having difficulty seeing a lot of things lately, and that’s the problem.

Your brushstrokes are off, I sign to her. The lines are crooked, and you’ve misjudged some of the hues.

Zhang Jing steps back from her canvas. Surprise lights her features for only a moment before despair sets in. This isn’t the first time these mistakes have happened. A nagging instinct tells me it won’t be the last. I make a small gesture, urging her to hand me her brush and paints. She hesitates and glances around the workroom to make sure none of our peers is watching. They’re all deeply engrossed in their own canvases, spurred on by the knowledge that our masters will arrive at any moment to evaluate our work. Their sense of urgency is nearly palpable. I beckon again, more insistently this time, and Zhang Jing yields her tools, stepping away to let me work.

Quick as lightning, I begin going over her canvas, repairing her imperfections. I smooth out the unsteady brushstrokes, thicken lines that are too thin, and use sand to blot out places where the ink fell too heavily. This calligraphy consumes me, just as art always does. I lose track of the world around me and don’t even really notice what her work says. It’s only when I finish and step back to check my progress that I take in the news she was recording.

Death. Starvation. Blindness.

Another grim day in our village.

I can’t focus on that right now, not with our masters about to walk in. Thank you, Fei, Zhang Jing signs to me before taking her tools back. I give a quick nod and then hurry over to my own canvas across the room, just as a rumbling in the floor signifies the entrance of the elders. I take a deep breath, grateful that I have once again saved Zhang Jing from getting into trouble. With that relief comes a terrible knowledge that I can no longer deny: My sister’s sight is fading. Our village came to terms with silence when our ancestors lost their hearing generations ago for unknown reasons, but being plunged into darkness? That’s a fate that scares us all.

I must push those thoughts from my mind and put on a calm face as my master comes strolling down the rows of canvas. There are six elders in the village, and each one oversees at least two apprentices. In most cases, each elder knows who his or her replacement will be—but with the way accidents and sickness happen around here, training a backup is a necessary precaution. Some apprentices are still competing to be their elder’s replacement, but I have no worries about my position.

Elder Chen comes to me now, and I bow low. His dark eyes, sharp and alert despite his advanced years, look past me to the painting. He wears light blue like the rest of us, but the robe he has on over his pants is longer than the apprentices’. It nearly reaches his ankles and is trimmed in purple silk thread. I always study that embroidery while he’s doing his inspections, and I never grow tired of it. There’s very little color in our daily lives, and that silk thread is one bright, precious spot. Fabric of any kind is a luxury here, where my people struggle daily simply to get food. Studying Elder Chen’s purple thread now, I think of the old stories about kings and nobles who dressed in silk from head to toe. The image dazzles me for a moment, transporting me beyond this workroom until I blink and reluctantly return my focus back to my work.

Elder Chen is very still as he takes in my illustration, his expression unreadable. Whereas Zhang Jing painted dreary news today, my task was to depict our latest food shipment, which included a rare surprise of radishes. At last, he unclasps his hands from in front of him. You captured the imperfections of the radishes’ skin, he signs. Not many others would have noticed such detail.

From him, that is high praise. Thank you, master, I say before bowing again.

He moves on to examine the work of his other apprentice, a girl named Jin Luan. She shoots a look of envy in my direction before also bowing low to our master. There’s never been any question who his favorite student is, and I know it must frustrate her to feel that no matter what she does, she never grasps that top spot. I am one of the best artists in our group, and we all know it. I make no apologies for my success, especially since I’ve given up so much to achieve it.

I look to the far side of the room, where Elder Lian is examining Zhang Jing’s calligraphy. Elder Lian’s face is as unreadable as my master’s as she takes in every detail of my sister’s canvas. I find I’m holding my breath, far more nervous than I was for my own inspection. Beside her, Zhang Jing is pale, and I know my sister and I are both braced for the same thing: Elder Lian calling us out for deceiving them about Zhang Jing’s sight. Elder Lian lingers much longer than Elder Chen did, but at long last, she gives a cursory nod of acceptance and strolls on to her next apprentice. Zhang Jing sags in relief.

We have tricked them again, but I can’t feel bad about that either. Not when Zhang Jing’s future is at stake. If the elders discover her vision is failing, she will almost certainly lose her apprenticeship and be sent to the mines. The very thought makes my chest tighten. In our village, there are really only three jobs: artist, miner, and supplier. Our parents were miners. They died young.

When all the inspections are finished, it is time for our morning announcements. Elder Lian is giving them today, and she steps up on a platform in the room to allow her hands to be visible to all who are gathered.

Your work is satisfactory, she begins. It’s the usual acknowledgment, and we all bow. When we are looking up again, she continues. Never forget how important what we do here is. You are part of an ancient and exalted tradition. Soon we will go out into the village and begin our daily observations. I know things are hard right now. But remember that it is not our place to interfere with them.

She pauses, her gaze traveling around the room to each of us as we nod in acknowledgment at a concept that has been driven into us with as much intensity as our art. Interference leads to distraction, interrupting both the natural order of the village’s life as well as accurate record keeping. We must be impartial observers. Painting the daily news has

been a tradition in our village ever since our people lost their hearing centuries ago. I’m told that before then, news was shouted by a town crier or simply passed orally from person to person. But I don’t even really know what “shouting” is.

We observe, and we record, Elder Lian reiterates. It is the sacred duty we have performed for centuries, and to deviate from it does a disservice both to our tasks and to the village. Our people need these records to know what is happening around them. And our descendants need our records so they can understand the way things have always been. Go to breakfast now, and then be a credit to our teachings.

We bow again and then shuffle out of the workroom, heading toward the dining hall. Our school is called the Peacock Court. It’s a name our ancestors brought with them from fairer, faraway parts of Beiguo beyond this mountain, meant to acknowledge the beauty we create within the school’s walls. Every day, we paint the news of our village for our people to read. Even if we are only recording the most basic of information—like a shipment of radishes—our work must still be immaculate and worthy of preservation. Today’s record will soon be put on display in our village’s heart, but first we have this small break.

Zhang Jing and I sit down cross-legged on the floor at a low table to wait for our meal. Servants come by and carefully measure out millet porridge, making sure each apprentice gets an equal amount. We have the same thing for breakfast each day, and while it chases the hunger away, it doesn’t exactly leave me feeling full either. But it’s more than the miners and suppliers get, so we must be grateful.

Zhang Jing pauses in her breakfast. It will not happen again, she signs to me. I mean it.

Hush, I say. It’s a topic she can’t even hint at in this place. And despite her bold words, there’s a fear in her face that tells me she doesn’t believe them anyway. Reports of blindness have been growing in our village for reasons that are just as mysterious as the deafness that fell upon our ancestors. Usually only miners go blind, which makes Zhang Jing’s current plight that much more mysterious.

A flurry of activity in my periphery startles me out of my thoughts. I look up and see that the other apprentices have also stopped eating, their gazes turned toward a door that leads from this dining room to the kitchen. A cluster of servants stands there, more than I normally see at once. Usually mindful of the differences in rank, they stay out of our way.

A woman I recognize as the head cook has emerged from the door, a boy scurrying in front of her. Cook is an extravagant term for her job, since there’s so little food and not much to be done with it. She also oversees running the Peacock Court’s servants. I flinch when she strikes the boy with a blow so hard that he falls to the floor. I’ve seen him around, usually doing the meanest of cleaning tasks. A frantically signed conversation is taking place between them.

—think you wouldn’t get caught? the cook demands. What were you thinking, taking more than your share?

It wasn’t for me! the boy tells her. It was for my sister’s family. They’re hungry.

We’re all hungry, the cook snaps back. That’s no excuse for stealing.

I give a sharp intake of breath as I realize what has happened. Food theft is one of the greatest crimes we have around here. The fact that it would occur among our servants, who are generally fed better than other villagers, is particularly shocking. The boy manages to get to his feet and bravely face the cook’s wrath.

They’re a mining family, and they’ve been sick, the boy says. The miners already get less food than we do, and they had their rations cut while not working. I was trying to make things fair.

The hard set of the cook’s face tells us she is unmoved. Well, now you can join them in the mines. We have no place here for thieves. I want you gone before we clear the breakfast dishes.

The boy falters at this, desperation filling his features. Please. Don’t send me to work with them. I’m sorry. I’ll give up my rations to make up for what I took. It won’t ever happen again.

I know it won’t happen again, the cook replies pointedly. She gives a curt nod to two of the burlier servants, and they each take one of the boy’s arms, hauling him out of the dining room. He tries to free himself and protest but can’t fight against both of them. The cook watches impassively while the rest of us gape. When he’s out of sight, she and the other servants not working our breakfast service disappear back into the kitchen. Zhang Jing and I exchange glances, too shocked for words. In his moment of weakness, that servant has just made his life significantly more difficult—and dangerous.

When we finish breakfast and head to the workroom, the theft is all anyone can talk about. Can you believe it? someone asks me. How dare he give our food to a miner!

The speaker’s name is Sheng. Like me, he is one of the top artists at the Peacock Court. Unlike me, he is descended from a family of artists and elders. I think he forgets sometimes that Zhang Jing and I are the first in our family to achieve this rank.

It is certainly a terrible thing, I respond neutrally. I don’t dare express my true feelings: that I have doubts about whether the food distribution is fair. I learned long ago that to keep my position in the Peacock Court, I must give up all sympathies to the miners and simply view them as our village’s workforce. Nothing more.

He deserves a worse punishment than dismissal, Sheng says ominously. Along with his skill in art, Sheng has the kind of brash confidence that makes people follow him, so I’m not surprised to see a few others walking near us nod in agreement. He lifts his head proudly at their regard, showing off fine, high cheekbones. Most of the girls around here would also agree he’s the most attractive boy in the school, but he’s never had much of an effect on me.

I hope that changes soon, as we are expected to marry someday.

Boldly, knowing I’m probably making a mistake, I ask, You don’t think the circumstances played a role in his actions? Wanting to help his sick family?

That’s no excuse, Sheng states. Everyone earns what they deserve around here—no more, no less. That’s balance. If you can’t fulfill your duty, you shouldn’t expect to be fed for it. Don’t you agree?

My heart aches at his words. I can’t help but give a quick glance at Zhang Jing, walking on my other side, before turning back to Sheng. Yes, I say bleakly. Yes, of course, I agree.

We apprentices begin gathering up our canvases to take them out for the other villagers to view. Some are still wet and require extra caution. As we step outside, the sun is well above the horizon, promising a warm and clear day to come. It shines on the green leaves of the trees among our village. Their branches create a canopy that shades much of the walkway to the village’s center. I watch the patterns the light creates on the ground when it’s filtered through the trees. I’ve often thought about painting that dappled light, if only I had the opportunity. But I never do.

I’d love to paint the mountains too. We are surrounded by them, and our village sits on top of one of the highest. It creates breathtaking views but also a number of difficulties for us. This peak is surrounded on three sides by steep cliffs. Our ancestors migrated here centuries ago along a pass on the mountain’s opposite side that was flanked by fertile valleys perfect for growing food. Around the time hearing disappeared, severe avalanches blocked the pass, filling it up with boulders and stones far taller than any man. It trapped our people up here and cut us off from growing crops anymore.

That was when our people worked out an arrangement with a township at the mountain’s base. Each day, most of our villagers work in the mines up here, hauling out loads of precious metals. Our suppliers send those metals to the township along a zip line that runs down the mountain. In return for the metal, the township sends us shipments of food since we can’t produce our own. The arrangement was working well until some of our miners began losing their sight and could no longer work. When the metals going down slowed, so did the food coming back up.

As my group moves closer to the center of the village, I see miners getting ready for the day’s work, dressed in their dull clothing with lines of weariness etched on their faces. Even children help out in the mines. They walk beside their parents and, in some cases, grandparents.

In the village’s heart, we find those who have lost their sight. Unable to see or hear, they have become beggars, huddled together and waiting for the day’s handouts. They sit immobile with their bowls, deprived of the ability to communicate, only able to wait for the feel of vibrations in the ground to let them know that people are approaching and that they might receive some kind of sustenance. I watch as a supplier comes by and puts half a bun in each beggar’s bowl. I remember reading about those buns in the record when they arrived a couple of days ago. They were already subpar then, most of them showing mold. But we can’t afford to throw away any food. That half bun is all the beggars will get until nightfall unless someone is kind enough to share from their own rations. The scene makes my stomach turn, and I avert my gaze from them as we walk toward the central stage where workers are already removing yesterday’s record.

A flash of bright color catches my eye, and I see a blue rock thrush land on the branch of a tree near the clearing. Much like Elder Chen’s silk trim, that brilliance draws me in. As I’m admiring the sheen of the bird’s azure feathers, he opens his mouth for a few seconds and then looks around expectantly. Not long after that, a duller female flies in and lands near him. I stare in wonder, trying to understand what just took place. How did he draw her to him? What could he have done that conveyed so much, even though she hadn’t seen him? I know from reading that something happened when he opened his mouth, that he “sang” to her and somehow brought her, even though she wasn’t nearby.

A nudge at my shoulder tells me it’s time to stop daydreaming. Our group has reached the dais in the village’s center, and most of the villagers have gathered to see our work. We climb the steps to the platform and hang our paintings. We’ve done this many times, and everyone knows their roles. What was a series of illustrations and calligraphy in the workshop now fits together as one coherent mural, presenting a thorough depiction of all that happened in the village yesterday to those gathered below. When I’ve hung my radishes, I shuffle back down with the other apprentices and watch the faces of the rest of the crowd as they read the record. I see furrowed brows and dark glances as they take in the latest reports of blindness and hunger. The radishes are no consolation. The art might be perfect, but it’s lost on my people in its bearing of such dreary news.