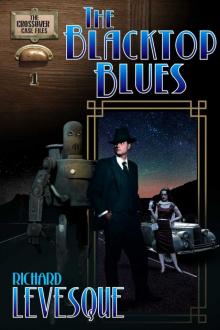

The Blacktop Blues: A Dieselpunk Adventure (The Crossover Case Files Book 1)

Richard Levesque

The Blacktop Blues

The Crossover Case Files

Book 1

Richard Levesque

The Blacktop Blues © 2021 Richard Levesque

All Rights Reserved

This is a work of fiction. Any resemblance to people living or dead is purely coincidental. Any historical figures, setting, or events described in this book are also a product of the author’s imagination and are not intended as depictions actual people, places, or events.

Cover design & composite ©2020 Duncan Eagleson - duncaneagleson.com

Cover images: Background © Duncan Eagleson

Man ©Ysbrandcosijn/stock.adobe.com

Woman © GoldenEyes71/stock.adobe.com

Used By Permission

All Rights Reserved

Table of Contents

Acknowledgements

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-One

Author’s Note

About the Author

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I am grateful to several people for their help in the writing of this book, including Jefferson Smith and my wife Karianne Levesque, who read early drafts and helped point the book in the right direction. I’m also grateful to Duncan Eagleson and Corvid Design for his work on the cover. Finally, as always, I’m grateful to my friends and family for putting up with me as I work on these books and for always believing in me, no matter how crazy the ideas may seem.

Click Here to Get Your Free Book Now

Or is it all only a dream? They say life is a dream, a precious poor dream at times—but I can’t stand another that won’t fit. It’s madness. And where did the dream come from?

—H.G. Wells, The Time Machine

Chapter One

Sid Drummond’s pawnshop was a packrat’s dream, the showroom cluttered with items for sale, some of which hadn’t been moved or cleaned in a decade. Located half a block from the docks, Sid’s was my first stop the morning I was discharged—but only because it would have been backtracking to go to Annabelle’s first.

Still in my uniform, it felt strange to be back in New York after six years at war, stranger still to be walking down a city street not blocked with rubble and bodies. I tried smiling at a few people I passed, just because I thought I should. A few smiled back, mostly women. A little kid threw me a salute. Most people didn’t seem to notice me, though.

This made me feel uneasy. It was like I had turned into The Invisible Man from the movies or something. As a result, I stood outside Sid’s for a minute when I got there, not sure of how much things had changed in the time I’d been away.

Once I was ready to open it, the door squeaked on its hinges, and the little bell above the threshold rang the way it always had. The sounds made me feel like I was home, and the sight of Sid’s crowded shop came close to erasing the weird feelings I’d had on the street. The merchandise formed an aisle lined with toolboxes, antiques, and racks of clothing, funneling customers toward the counter where the jewelry and other expensive items were housed. On the wall behind the counter were framed paintings, a trombone on a shelf, and an old velocipede held up on pegboard. Above the aisle, guitars hung down like stalactites in a rainbow of colors.

Sid was behind the counter, a jeweler’s loupe screwed into his remaining eye. He looked up when the bell sounded, an odd sight with the loupe in one eye socket and a black patch covering the other. His white hair had thinned in the time I’d been gone, but I was glad to see he hadn’t gotten any rounder. Before the door closed behind me, the old man put down the watch he was working on and reached up to remove the loupe. I watched him blink at me as I traversed the aisle, and when he was finally able to focus, his face broke into a wide smile.

“Jed!” he called out happily. Then he lifted the hinged section of his counter and bustled out to meet me, giving me a back-slapping hug in the middle of the store. “It’s good to see you, boy!” he said, addressing me the way he had since I’d been a fourteen-year-old coming in here to play with the guitars. It felt a little strange to be called “boy” when I was a month away from turning thirty, but I let it go.

“Good to see you, too, Sid. How’ve you been?”

“How have I been?” he asked incredulously. “You know me. Nothing changes around here. How have you been? That’s the question.”

“Good, Sid,” I said. “I’m good.”

“Just get back?”

“Docked in the middle of the night. Took all morning to get the paperwork done, but I’m a free man now.”

“Great, great,” he said, his smile still wide. He was staring at me with his lone eye like he couldn’t believe I was really here. “You came through it all right then?”

“As all right as can be,” I said, not wanting to think about all the close calls, especially the one that had come right before the end of the fighting.

I’m sure Sid was able to see through the evasiveness of my answer, even with one eye. He let it go. “That’s great,” he said, “Great. I worried about you, you know?”

“I appreciate that, Sid. I really do.”

We talked for a few minutes, Sid asking about the places I’d been stationed while avoiding questions about the battles I’d been in.

“It’s too bad you boys couldn’t put the Nazis down for good,” he said after a while, pronouncing the word nazzies. It wasn’t the first time I’d heard this. Coming from anyone else, it would have been hard to hear the comment without reading it as a veiled criticism, as though I’d had something to do with the decision to bring the war to an end before the Germans had been good and beaten. From Sid, though, I knew it was just talk, no judgement involved.

“I feel the same way, Sid,” I said. “But…you know, they had the bomb, and we had the bomb, too. You saw the tests?”

“I did.”

I shrugged. “What could we do?”

“What we did,” he said with a sigh. “It’s just a shame it had to go that way.”

“You’re right.” A pause hung between us for a few seconds, and then he said, “So, you got any plans?”

I shrugged. “Nothing firm. I’m going to Annabelle’s next. We’ll see from there.”

“That’s good, that’s good. I take it you came to get your other girl first?”

“I did,” I said. “If you’ve still got her.”

“Still got her?” he said with a laugh. “You kidding me?” He slapped my back again and said, “I strung her up fresh when I heard the truce got signed, just so she’d be ready to go when you came through that door. Wait here. I’ll go get her.”

I did as he asked, waiting in the aisle with a wooden horned Del Monte phonograph on one side of me and a battered steamer trunk on the other. Sid went behind the counter and through the curtained doorway that hid his inner sanctum from the public. I listened to him mumbling back there, his voice drowned out by the sound of big things being moved around.

“Need any help?” I called out.

“No, no,” he said, his voice still cheery.

A couple minutes later, he came out with a blond guitar case, gently setting it on the countertop with the buckles facing me. I leaned forward and flipped the latches, opening the case to see my guitar resting before me. It was a ’38 Harmon archtop, its red body shining like it was nowhere near ten years old. I ran my fingers across the new strings and the mother-of-pearl accents on the neck. The guitar was more beautiful than I remembered it.

“Thanks for storing it, Sid,” I said. “You sure I can’t pay you for the trouble?”

I knew I couldn’t afford the cost of a six-year pawn ticket, but I still felt like I owed the old man for the space the Harmon had taken since I’d been called up.

“Trouble? Trouble? Are you kidding me? After what you did for me? Hell, boy, keeping this old guitar case is the least I could do.”

A year before the war broke out, Sid had had an accident when a gun he was cleaning went off. He’d been getting ready to put it up for sale in the display case, but the bullet he’d overlooked changed his plans. It had cost him his eye, and he’d been in the hospital for almost a month. When he came back, he found that I’d kept the shop running for him. I might have made a few mistakes in some of the deals I cut with his customers, but overall my management of things hadn’t been a disaster. I’d even cleaned up the blood that had spattered on the display case and the wall behind it—and I’d refused to take a penny in exchange. I hadn’t felt like Sid owed me then—it was just something I did for a friend in need—and I didn’t feel like he owed me now.

“At least let me pay for the strings,” I said.

“Get out of here! Pay for the strings! You kidding me?”

I smiled and closed the case. “I guess so, Sid. Thanks.”

“It’s nothing.” He looked me up and down, the smile never having left his face. “So, you seriously got nothing lined up?”

“Just Annabelle,” I said.

He nodded. “Well, I see you’ve still got all your fingers. If you’re interested, one of my poker buddies runs a club over on Hudson called the Break O’ Dawn. Told me the other night he’s looking for a guitar player. The position might still be open. You interested?”

“Sure,” I said.

“Great. I’ll call him up. Tell him you’ll come by this evening?”

I shrugged, not sure I wanted to have to tell Annabelle I’d need to cut our reunion short to go see about a job. Still, I couldn’t dismiss the offer completely. “Yeah, tell him I’ll come. I just don’t know what time.”

He gave me a knowing smile, reached across the counter to slap my back again, and said, “Go get your girl.” Then he closed the lid on the guitar case and added, “Your other girl, I mean.”

* * * * *

“She’s not here,” the old woman said as soon as she opened the door. No greeting. No welcome back.

I’d been expecting Annabelle to open the door, not her grandmother. I’d also expected a big kiss, a squeal of joy, and arms wrapped around my neck. Instead, I faced the mixed expression of a bespectacled septuagenarian. The old lady looked glad to see me, sure, but also let down, almost disappointed, like I’d knocked a homerun out of the park in what had turned out to be a football game.

Not here, the words echoed in my mind, and I knew she hadn’t just meant that Annabelle had gone to the store or picked up an afternoon shift at the airship factory. “Not here” meant she was gone. “Not here” meant I’d missed my chance, and even though I understood what the words meant, they still filled me with confusion.

“You may as well come in,” the old woman said with a sigh, and she stepped aside to let me through the door.

The little living room was like I remembered it—a battered upright piano in one corner, old family photos on the walls, an armchair that had once been overstuffed, a coffee table that needed varnishing, and a sofa that Annabelle’s grandmother always called a “davenport.” Annabelle and I had spent a lot of time on that sofa, late evenings when her grandmother had conveniently slipped off to her upstairs bedroom. I sat on it now with a feeling far different from what I’d known the last time I was in this house.

The old woman didn’t sit. Instead, she went to the kitchen to fix a tray for tea—without asking if I wanted any and apparently having forgotten that I never drink the stuff. She stayed gone the whole time it took the kettle to boil, leaving me alone with a slow boil of my own. My left hand gripped the arm of the sofa so tightly my knuckles turned white, and when Annabelle’s grandmother came back in with the tray, it was all I could do to keep from leaping up to start firing questions at her.

Somehow, I kept my composure and waited until she’d sat across from me and poured the water.

At that point, I couldn’t hold it in any longer. “Where’d she go?” I asked.

She sighed, that same look of disappointment on her face, and I knew it meant she blamed me—at least a little—for whatever had happened when I was gone.

“The war lasted a long time, Jed,” she said, and the absurdity of this statement pushed me close to laughter. I was sure it had seemed a long time to her, but to me and the guys I’d gone through it with, the six year stretch in Europe had been an eternity. It felt like I’d already lived a dozen lifetimes—and survived more than one death—in the time I’d been gone. And here I was, still dressed in my uniform, come home to something less than a hero’s welcome.

“Yes,” was all I managed to say.

“Annabelle waited for you,” she said, not making eye contact with me. Instead, her gaze seemed to focus on the newspaper on the coffee table, its headline saying something about FDR’s legacy now that his fourth term in office was a few months away from being done. Still not looking at me, she went on. “She waited the whole time. And then…about a month ago, just after the truce, she met some new people. Started spending all her time with them. They were from out west. Movie people, most of them.”

I seethed at this, expecting one of these “movie people” to have been a man, a suave one with Hollywood good looks, a guy who’d used his privilege to keep himself out of the war so he could swoop in on all the women the GIs had left behind. He’d have charm and money, and he’d be free of scars and night terrors where he’d wake up screaming, certain that he’d just had his face blown off.

“What did they want with her?” I managed to ask.

She shrugged. “I can’t really say. Annabelle never really said. I never met any of them, and Annabelle never told me their names. She just said they were ‘wonderful’ and ‘generous’ and that they were going to take such good care of her. I tried to talk her out of going, Jed. I really did.”

“Going?” I interrupted. “To Hollywood?”

She nodded. “On an airship. She was so excited because she’d never flown before.” She let out a sigh and then continued. “What sense does it make for a grown woman to run off with a bunch of folks she’s just met when she should be looking to get herself a better job or wait for a fella like you to come back from the war? It was like she wasn’t in her right mind from the minute she met those folks, Jed. Not in her right mind.” She shook her head at this last bit while I tried to keep my sense of betrayal in check.

I should say at this point that the idea of rekindling things with Annabelle after the war had never been an actual promise between us, more an unspoken near-certainty. We’d been together for a year before the war, but when my number came up, we’d officially set each other free—at my coaxing. I remember that tore her up pretty good, as she knew the only reason I’d pushed for it was so she’d be able to get back on her feet easier if I ended up as fertilizer in a French field. And she’d been right. Still, despite the official split, I hadn’t forgotten her, and her letters had helped get me through the rough days and the long nights. I won’t lie to you, though. There were a few nights where the letters weren’t enough, and I’d found comfort elsewhere, but I always felt rotten about it, and the momentary distraction was never wor

th the duffle full of guilt I had to lug around for weeks afterwards—which I suppose is an indication that the official split never really took for me.

And now I was back, and she wasn’t here—despite the way she’d assured me in every missive that she was waiting for me, that everything would be just like it had been before despite our “agreement” that we’d been split up.

It took me a moment to screw up the courage to ask, “Did she say anything about me? About me coming home?”

“She gave me this.”

Rising from the lumpy armchair, she went to the piano. There was an envelope on the music stand in front of a battered copy of sheet music for “When They Come Home Again,” a song Annabelle had learned to play while I was gone, or so she’d written in one of her letters. The old woman retrieved the envelope and walked it back to me.

It was sealed and had my name—Jed—written in large, flowing letters on the front. I pondered it for a moment while Annabelle’s grandmother fished a teabag from her cup with a spoon, strained it against the porcelain, and leaned back to take a sip.

I didn’t want to open it in front of her. At the same time, I knew I couldn’t wait. The old woman had a look of anticipation on her face that told me she’d been dying to know what was inside the envelope since the minute it had been placed on the piano, and though I knew I could have just as easily gotten up and walked out the door with it, something made me stay on the sofa and pry my thumbnail into the sealed flap.

Still ignoring my tea, I read the letter silently.

“Dear Jed,” it started. “I’m leaving this letter with Granny since I figure there’s a better chance of it getting into your hands this way. I’ve been reading the papers and following the news, and everything seems so confusing with the truce and what they’re saying about soldiers being shuffled around before they get discharged. I’m worried if I try to send this overseas, it’s going to miss you and get lost and you’ll never know what I wanted to say to you. But I know you’ll come home soon and try to find me first thing once you get stateside, so Granny will give it to you.