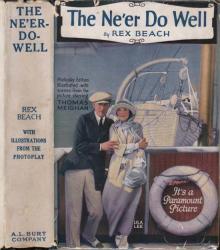

The Ne'er-Do-Well

Rex Beach

Produced by Charles Franks and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team.

THE NE'ER-DO-WELL

By REX BEACH

Author of "THE SILVER HORDE" "THE SPOILERS" "THE IRON TRAIL" Etc.

Illustrated

TO

MY WIFE

CONTENTS

I. VICTORY

II. THE TRAIL DIVIDES

III. A GAP

IV. NEW ACQUAINTANCES

V. A REMEDY IS PROPOSED

VI. IN WHICH KIRK ANTHONY IS GREATLY SURPRISED

VII. THE REWARD OF MERIT

VIII. EL COMANDANTE TAKES A HAND

IX. SPANISH LAW

X. A CHANGE OF PLAN

XI. THE TRUTH ABOUT MRS. CORTLANDT

XII. A NIGHT AT TABOGA

XIII. CHIQUITA

XIV. THE PATH THAT LED NOWHERE

XV. ALIAS JEFFERSON LOCKE

XVI. "8838"

XVII. GARAVEL THE BANKER

XVIII. THE SIEGE OF MARIA TORRES

XIX. "LA TOSCA"

XX. AN AWAKENING

XXI. THE REST OF THE FAMILY

XXII. A CHALLENGE AND A CONFESSION

XXIII. A PLOT AND A SACRIFICE

XXIV. A BUSINESS PROPOSITION

XXV. CHECKMATE!

XXVI. THE CRASH

XXVII. A QUESTION

XXVIII. THE ANSWER

XXIX. A LAST APPEAL

XXX. DARWIN K ANTHONY

THE NE'ER-DO-WELL

I

VICTORY

It was a crisp November night. The artificial brilliance of Broadwaywas rivalled by a glorious moonlit sky. The first autumn frost was inthe air, and on the side-streets long rows of taxicabs were standing,their motors blanketed, their chauffeurs threshing their arms to routthe cold. A few well-bundled cabbies, perched upon old-style hansoms,were barking at the stream of hurrying pedestrians. Against abackground of lesser lights myriad points of electric signs flashedinto everchanging shapes, winking like huge, distorted eyes; fancifuldesigns of liquid fire ran up and down the walls or blazed forth inlurid colors. From the city's canons came an incessant clanging roar,as if a great river of brass and steel were grinding its way toward thesea.

Crowds began to issue from the theatres, and the lines of waitingvehicles broke up, filling the streets with the whir of machinery andthe clatter of hoofs. A horde of shrill-voiced urchins pierced theconfusion, waving their papers and screaming the football scores at thetops of their lusty lungs, while above it all rose the hoarse tones ofcarriage callers, the commands of traffic officers, and the din ofstreet-car gongs.

In the lobby of one of the playhouses a woman paused to adjust herwraps, and, hearing the cries of the newsboys, petulantly exclaimed:

"I'm absolutely sick of football. That performance during the third actwas enough to disgust one."

Her escort smiled. "Oh, you take it too seriously," he said. "Thoseboys don't mean anything. That was merely Youth--irrepressible Youth,on a tear. You wouldn't spoil the fun?"

"It may have been Youth," returned his companion, "but it sounded morelike the end of the world. It was a little too much!"

A bevy of shop-girls came bustling forth from a gallery exit.

"Rah! rah! rah!" they mimicked, whereupon the cry was answered by ahundred throats as the doors belched forth the football players andtheir friends. Out they came, tumbling, pushing, jostling; greetingscowls and smiles with grins of insolent good-humor. In their handswere decorated walking-sticks and flags, ragged and tattered as if fromlong use in a heavy gale. Dignified old gentlemen dived among them inpursuit of top-hats; hysterical matrons hustled daughters intocarriages and slammed the doors.

"Wuxtry! Wuxtry!" shrilled the newsboys. "Full account of the big game!"

A youth with a ridiculous little hat and heliotrope socks dashed intothe street, where, facing the crowd, he led a battle song of hisuniversity. Policemen set their shoulders to the mob, but, though theymet with no open resistance, they might as well have tried to dislodgea thicket of saplings. To-night football was king.

Out through the crowd came a score of deep-chested young men movingtogether as if to resist an attack, whereupon a mighty roar went up.The cheer-leader increased his antics, and the barking yell changed toa measured chant, to the time of which the army marched down the streetuntil the twenty athletes dodged in through the revolving doors of acafe, leaving Broadway rocking with the tumult.

All the city was football-mad, it seemed, for no sooner had thenew-comers entered the restaurant than the diners rose to wave napkinsor to cheer. Men stepped upon chairs and craned for a better sight ofthem; women raised their voices in eager questioning. A gentleman inevening dress pointed out the leader of the squad to his companions,explaining:

"That is Anthony--the big chap. He's Darwin K. Anthony's son. You'veheard about the Anthony bill at Albany?"

"Yes, and I saw this fellow play football four years ago. Say! That wasa game."

"He's a worthless sort of chap, isn't he?" remarked one of the women,when the squad had disappeared up the stairs.

"Just a rich man's son, that's all. But he certainly could playfootball."

"Didn't I read that he had been sent to jail recently?"

"No doubt. He was given thirty days."

"What! in PRISON?" questioned another, in a shocked voice.

"Only for speeding. It was his third offence, and his father let himtake his medicine."

"How cruel!"

"Old man Anthony doesn't care for this sort of thing. He's right, too.All this young fellow is good for is to spend money."

Up in the banquet-hall, however, it was evident that Kirk Anthony wasmore highly esteemed by his mates than by the public at large. He wastheir hero, in fact, and in a way he deserved it. For three yearsbefore his graduation he had been the heart and sinew of the universityteam, and for the four years following he had coached them, preferringthe life of an athletic trainer to the career his father had offeredhim. And he had done his chosen work well.

Only three weeks prior to the hard gruel of the great game the elevenhad received a blow that had left its supporters dazed and despairing.There had been a scandal, of which the public had heard little and thestudents scarcely more, resulting in the expulsion of the five bestplayers of the team. The crisis might have daunted the most resourcefulof men, yet Anthony had proved equal to it. For twenty-one days he hadlabored like a real general, spending his nights alone with diagramsand little dummies on a miniature gridiron, his days in carefulcoaching. He had taken a huge, ungainly Nova Scotian lad named Ringoldfor centre; he had placed a square-jawed, tow-headed boy from Duluth inthe line; he had selected a high-strung, unseasoned chap, who for twoyears had been eating his heart out on the side-lines, and made himinto a quarter-back.

Then he had driven them all with the cruelty of a Cossack captain; andwhen at last the dusk of this November day had settled, new footballhistory had been made. The world had seen a strange team snatch victoryfrom defeat, and not one of all the thirty thousand onlookers but knewto whom the credit belonged. It had been a tremendous spectacle, andwhen the final whistle blew for the multitude to come roaring downacross the field, the cohorts had paid homage to Kirk Anthony, theweary coach to whom they knew the honor belonged.

Of course this fervid enthusiasm and hero-worship was all veryimmature, very foolish, as the general public acknowledged after it hadtaken time to cool off. Yet there was something appealing about it,after all. At any rate, the press deemed the public sufficientlyinterested in the subject to warrant giving it considerable prominence,and the name of Darwin K. Anthony's son was published far and wide.

Naturally, the newspaper

s gave the young man's story as well as ahistory of the game. They told of his disagreement with his father; ofthe Anthony anti-football bill which the old man in his rage had driventhrough the legislature and up to the Governor himself. Some of themeven printed a rehash of the railroad man's famous magazine attack onthe modern college, in which he all but cited his own son as an exampleof the havoc wrought by present-day university methods. The elderAnthony's wealth and position made it good copy. The yellow journalsliked it immensely, and, strangely enough, notwithstanding thepositiveness with which the newspapers spoke, the facts agreedessentially with their statements. Darwin K. Anthony and his son hadquarrelled, they were estranged; the young man did prefer idleness toindustry. Exactly as the published narratives related, he toiled not atall, he spun nothing but excuses, he arrayed himself in sartorialglory, and drove a yellow racing-car beyond the speed limit.

It was all true, only incomplete. Kirk Anthony's father had even betterreasons for his disapproval of the young man's behavior than appeared.The fact was that Kirk's associates were of a sort to worry anyobservant parent, and, moreover, he had acquired a renown in that partof New York lying immediately west of Broadway and north ofTwenty-sixth Street which, in his father's opinion, added not at all tothe lustre of the family name. In particular, Anthony, Sr., wasprejudiced against a certain Higgins, who, of course, was his son'sboon companion, aid, and abettor. This young gentleman was a lean,horse-faced senior, whose unbroken solemnity of manner had more thanonce led strangers to mistake him for a divinity student, though closeracquaintance proved him wholly unmoral and rattle-brained. Mr. Higginspossessed a distorted sense of humor and a crooked outlook upon life;while, so far as had been discovered, he owned but two ambitions: oneto whip a policeman, the other to write a musical comedy. Neitherseemed likely of realization. As for the first, he was narrow-chestedand gangling, while a brief, disastrous experience on the college paperhad furnished a sad commentary upon the second.

Not to exaggerate, Darwin K. Anthony, the father, saw in the person ofAdelbert Higgins a budding criminal of rare precocity, and a menace tohis son; while to the object of his solicitude the aforesaid criminalwas nothing more than an entertaining companion, whose bizarredisregard of all established rules of right and wrong matched well withhis own careless temper. Higgins, moreover, was an ardent follower ofathletics, revolving like a satellite about the football stars, andattaching himself especially to Kirk, who was too good-natured to findfault with an honest admirer.

It was Higgins this evening who, after the "cripples" had deserted andthe supper party had dwindled to perhaps a dozen, proposed to make anight of it. It was always Higgins who proposed to make a night of it,and now, as usual, his words were greeted with enthusiasm.

Having obtained the floor, he gazed owlishly over the flushed facesaround the table and said:

"I wish to announce that, in our little journey to the underworld, wewill visit some places of rare interest and educational value. First wewill go to the House of Seven Turnings."

"No poetry, Hig!" some one cried. "What is it?"

"It is merely a rendezvous of pickpockets and thieves, accessible onlyto a chosen few. I feel sure you will enjoy yourselves there, for thebartender has the secret of a remarkable gin fizz, sweeter than amaiden's smile, more intoxicating than a kiss."

"Piffle!"

"It is a place where the student of sociology can obtain a world ofvaluable information."

"How do we get in?"

"Leave that to old Doctor Higgins," Anthony laughed. "To get out is thedifficulty."

"Oh, I guess we'll get out," said the bulky Ringold.

"After we have concluded our investigations at the House of SevenTurnings," continued the ceremonious Higgins, "we will go to the Palaceof Ebony, where a full negro orchestra--"

"The police closed that a week ago."

"But it has reopened on a scale larger and grander than ever."

"Let's take in the Austrian Village," offered Ringold.

"Patiently! Patiently, Behemoth! We'll take 'em all in. However, I wishto request one favor. If by any chance I should become embroiled with aminion of the law, please, oh please, let me finish him."

"Remember the last time," cautioned Anthony. "You've never come home awinner."

"Enough! Away with painful memories! All in favor--"

"AYE!" yelled the diners, whereupon a stampede ensued that caused thewaiters in the main dining-room below to cease piling chairs upon thetables and hastily weight their napkins with salt-cellars.

But the crowd was not combative. They poured out upon the street in thebest possible humor, and even at the House of Seven Turnings, asHiggins had dubbed the "hide-away" on Thirty-second Street, they madeno disturbance. On the contrary, it was altogether too quiet for mostof them, and they soon sought another scene. But there were desertersen route to the Palace of Ebony, and when in turn the joys of a fullnegro orchestra had palled and a course was set for the AustrianVillage, the number of investigators had dwindled to a choicehalf-dozen.

These, however, were kindred spirits, veterans of many a midnightescapade, composing a flying squadron of exactly the right proportionsfor the utmost efficiency and mobility combined.

The hour was now past a respectable bedtime and the Tenderloin hadawakened. The roar of commerce had dwindled away, and the comparativesilence was broken only by the clang of an infrequent trolley. Thestreets were empty of vehicles, except for a few cabs that followed thelittle group persistently. As yet there was no need of them. The crowdwas made up, for the most part, of healthy, full-blooded boys, freshfrom weeks of training, strong of body, and with stomachs likegalvanized iron. They showed scant evidence of intoxication. As for theweakest member of the party, it had long been known that one drink madeHiggins drunk, and all further libations merely served to maintain himin status quo. Exhaustive experiments had proved that he was able toretain consciousness and the power of locomotion until the first streakof dawn appeared, after which he usually became a burden. For thepresent he was amply able to take care of himself, and now, althoughhis speech was slightly thick, his demeanor was as didactic and severeas ever, and, save for the vagrant workings of his mind, he might havepassed for a curate. As a whole, the crowd was in fine fettle.

The Austrian Village is a saloon, dance-hall, and all-night restaurant,flourishing brazenly within a stone's throw of Broadway, and it iscounted one of the sights of the city. Upon entering, one may passthrough a saloon where white-aproned waiters load trays and wrangleover checks, then into a ball-room filled with the flotsam and jetsamof midnight Manhattan. Above and around this room runs a white-and-goldbalcony partitioned into boxes; beneath it are many tables separatedfrom the waxed floor by a railing. Inside the enclosure men instreet-clothes and smartly gowned girls with enormous hats revolvenightly to the strains of an orchestra which nearly succeeds indrowning their voices. From the tables come laughter and snatches ofsong; waiters dash hither and yon. It is all very animated and gay onthe surface, and none but the closely observant would note theweariness beneath the women's smiles, the laughter notes thatoccasionally jar, or perceive that the tailored gowns are imitations,the ermines mainly rabbit-skins.

But the eyes of youth are not analytical, and seen through a rosy hazethe sight was inspiriting. The college men selected a table, and,shouldering the occupants aside without ceremony, seated themselves andpounded for a waiter.

Padden, the proprietor, came toward them, and, after greeting Anthonyand Higgins by a shake of his left hand, ducked his round gray head inacknowledgment of an introduction to the others.

"Excuse my right," said he, displaying a swollen hand criss-crossedwith surgeon's plaster. "A fellow got noisy last night."

"D'jou hit him?" queried Higgins, gazing with interest at theproprietor's knuckles.

"Yes. I swung for his jaw and went high. Teeth--" Mr. Padden said,vaguely. He turned a shrewd eye upon Anthony. "I heard about the gameto-day. That was all right."

K

irk grinned boyishly. "I didn't have much to do with it; these are thefellows."

"Don't believe him," interrupted Ringold.

"Sure! he's too modest," Higgins chimed in. "Fine fellow an' all that,understand, but he's got two faults--he's modest and he's lazy. He'scaused a lot of uneasiness to his father and me. Father's a fine man,too." He nodded his long, narrow head solemnly.

"We know who did the trick for us," added Anderson, the straw-hairedhalf-back.

"Glad you dropped in," Mr. Padden assured them. "Anything you boys wantand can't get, let me know."

When he had gone Higgins averred: "There's a fine man--peaceful,refined--got a lovely character, too. Let's be gentlemen while we're inhis place."

Ringold rose. "I'm going to dance, fellows," he announced, and hiscompanions followed him, with the exception of the cadaverous Higgins,who maintained that dancing was a pastime for the frivolous and weak.

When they returned to their table they found a stranger was seated withhim, who rose as Higgins made him known.

"Boys, meet my old friend, Mr. Jefferson Locke, of St. Louis. He's allright."

The college men treated this new recruit with a hilarious cordiality,to which he responded with the air of one quite accustomed to suchreunions.

"I was at the game this afternoon," he explained, when the greetingswere over, "and recognized you chaps when you came in. I'm a footballfan myself."

"You look as if you might have played," said Anthony, sizing up thebroad frame of the Missourian with the critical eye of a coach.

"Yes. I used to play."

"Where?"

Mr. Locke avoided answer by calling loudly for a waiter, but when theorders had been taken Kirk repeated:

"Where did you play, Mr. Locke?"

"Left tackle."

"What university?"

"Oh one of the Southern colleges. It was a freshwater school--youwouldn't know the name." He changed the subject quickly by adding:

"I just got into town this morning and I'm sailing to-morrow. Icouldn't catch a boat to-day, so I'm having a little blow-out on my ownaccount. When I recognized you all, I just butted in. New York is alonesome place for a stranger. Hope you don't mind my joining you."

"Not at all!" he was assured.

When he came to pay the waiter he displayed a roll of yellow-backedbills that caused Anthony to caution him:

"If I were you I'd put that in my shoe. I know this place."

Locke only laughed. "There's more where this came from. However, that'sone reason I'd like to stick around with you fellows. I have an ideaI've been followed, and I don't care to be tapped on the head. If youwill let me trail along I'll foot the bills. That's a fair proposition."

"It certainly sounds engaging," cried Higgins, joyously. "The sight ofthat money awakens a feeling of loyalty in our breasts. I speak for allwhen I say we will guard you like a lily as long as your money lasts,Mr. Locke."

"As long as we last," Ringold amended.

"It's a bargain," Locke agreed. "Hereafter I foot the bills. You're myguests for the evening, understand. If you'll agree to keep me companyuntil my ship sails I'll do the entertaining."

"Oh, come now," Anthony struck in. "The fellows are just fooling.You're more than welcome to stay with us if you like, but we can't letyou put up for it."

"Why not? We'll make a night of it. I'll show you how we spend money inSt. Louis. I'm too nervous to go to bed."

Anthony protested, insisting that the other should regard himself asthe guest of the crowd; but as Locke proved obdurate the question wasallowed to drop until later, when Kirk found himself promoted by tacitconsent to the position of host for the whole company. This was alittle more than he had bargained for, but the sense of havingtriumphed in a contest of good-fellowship consoled him. Meanwhile, thestranger, despite his avowedly festive spirit, showed a certain reserve.

When the music again struck up he declined to dance, preferring toremain with Higgins in their inconspicuous corner.

"There's a fine fellow," the latter remarked, following his bestfriend's figure with his eyes, when he and Locke were once more alone."Sweet nature."

"Anthony? Yes, he looks it."

"He's got just two faults, I always say: he's too modest by far andhe's lazy--won't work."

"He doesn't have to work. His old man has plenty of coin, hasn't he?"

"Yes, and he'll keep it, too. Heartless old wretch. Mr.--What's yourname, again?"

"Locke."

"Mr. Locke." The speaker stared mournfully at his companion. "D'youknow what that unnatural parent did?"

"No."

"He let his only son and heir go to jail."

Mr. Jefferson Locke, of St. Louis, started; his wandering, watchfuleyes flew back to the speaker.

"What! Jail?"

"That's what I remarked. He allowed his own flesh and blood to languishin a loathsome cell."

"What for? What did they get him for?" queried the other, quickly.

"Speeding."

"Oh!" Locke let himself back in his chair.

"Yes sir, he's a branded felon."

"Nonsense. That's nothing."

"But we love him just the same, criminal though he is" said Higgins,showing a disposition to weep. "If he were not such a strong, patientsoul it might have ruined his whole life."

Mr. Locke grunted.

"S'true! You've no idea the disgrace it is to go to jail."

The Missourian stirred uneasily. "Say, it gets on my nerves to sitstill," said he. "Let's move around."

"Patiently! Patiently! Somebody's sure to start something before long."

"Well, I don't care to get mixed up in a row."

Higgins laid a long, white hand upon the speaker's arm. "Then stay withus, Mr.--Locke. If you incline to peace, be one of us. We're a flock ofsucking doves."

The dancers came crowding up to the table at the moment, and Ringoldsuggested loudly: "I'm hungry; let's eat again."

His proposal met with eager response.

"Where shall we go?" asked Anderson.

"I just fixed it with Padden for a private room upstairs," Anthonysaid. "All the cafes are closed now, and this is the best place in townfor chicken creole, anyhow."

Accordingly he led the way, and the rest filed out after him; but asthey left the ball-room a medium-sized man who had recently enteredfrom the street caught a glimpse of them, craned his neck for a betterview, then idled along behind.