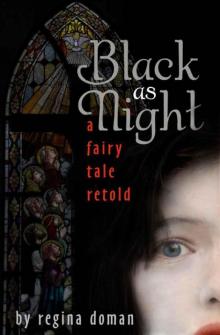

Black as Night: A Fairy Tale Retold

Regina Doman

Books by Regina Doman

The Fairy Tale Novels

The Shadow of the Bear: A Fairy Tale Retold

Black as Night: A Fairy Tale Retold

Waking Rose: A Fairy Tale Retold

The Midnight Dancers: A Fairy Tale Retold

Alex O’Donnell and the Forty Cyber-thieves

For children:

Angel in the Waters

Edited by Regina Doman:

Catholic, Reluctantly: John Paul 2 High Book One

Trespasses Against Us: John Paul 2 High Book Two

Summer of My Dissent: John Paul 2 High Book Two

By Christian M. Frank

Awakening: A Crossroads in Time Book

By Claudia Cangilla McAdam

Text copyright 2004 by Regina Doman

Originally published by Bethlehem Books, Bathgate, North Dakota in 2004

Revised paperback edition copyright 2007 by Regina Doman

Interior artwork copyright 2007 by Joan Coppa Drennen

2007 cover design by Regina Doman

All rights reserved.

You Take My Breath Away

Words and Music by Claire Hamill

Copyright © 1975 by DECOY MUSIC LTD.

Copyright Renewed

All Rights Controlled and Administered by UNIVERSAL-POLYGRAM INTERNATIONAL PUBLISHING, INC.

All Rights Reserved Used by Permission

Reprinted by permission of Hal Leonard Corporation

Chesterton Press

P.O. Box 949

Front Royal, Virginia

www.fairytalenovels.com

www.reginadoman.com

Summary: Over the summer in New York City, seven friars who work with the homeless find a runaway girl named Nora, while Bear Denniston searches for his missing girlfriend, Blanche, in a suspenseful retelling of the Snow White story.

ISBN: 978-0-9819-3182-1

Printed in the United States of America

This one’s for the boys–

my brothers, my brothers-in-law,

my friends, my cousins,

my husband, my sons.

To all you members of the male gender

who have been my friends,

brothers, and comrades throughout my life,

I dedicate this book in particular gratitude,

with thanksgiving to the Father who made you,

and to all those boys

trying to survive the streets of New York City,

some of whom I knew for a brief time,

and of course,

to the Friars.

Chapter One

It was night.

In most places, Night is a time for sleep, calm, and mystery. But not in New York City.

In the tangled thicket of the urban landscape, millions of streetlights, arcade signs, neon tubes, and incandescent bulbs conspired every evening to murder the night, shedding their unearthly glow. The glow grew stronger as Night slipped in with her gray wool cloak and dropped it softly over the streets and subways.

The subway train rushed through the hot summer night like a sleepless dragon bellowing and hurtling along its metal track towards West 55th Street in the Bronx. Two youths slipped like phantoms from car to car, casing each jointed metal compartment for easy cash.

The older, fair-haired one first noticed the girl through the door window in the swaying car ahead. She looked lost, frozen. She didn’t see the two vicious denizens of the Night, but they saw her—and they saw the purse clutched tightly in her lap.

This was it. This girl with her short, ragged, black hair, white skin, and eyes red from crying was their hit. She was alone in the car, staring at the floor, apparently not aware of anything around her. It was after three in the morning. As if on cue, the boys both checked over their shoulders to see if they were watched, grinned at each other and pushed through the separating door.

She looked up when they came in and she saw. At once. What they intended to do.

Her cry of surprise and fear was lost as the rocking car made a rough and deafening turn on the tracks. She stumbled to her feet, prepared to run. But there was nowhere to go.

It was too easy. They were fifteen and nineteen years old, and used to violence. The bleach-blond nineteen-year-old shoved her onto the car’s dirty linoleum floor. She fell, her pale yellow flowered print dress splatting under her like a smashed flower. The younger, bigger one, with the earring, grabbed her bag.

The girl didn’t seem to care. She scrambled to her feet, resurrecting quickly and silently, and jumped for the emergency cord. He lunged after her and knocked her against the seats. A wail and moaning seemed to break forth from the beast’s belly, as the tunnel walls suddenly widened out. The girl screamed and shoved him away from her. He fell onto the seats and banged his head against the edge.

It was time to move. The train was coming to a halt, a station careened towards them. The bigger boy stuffed the purse inside his light jacket and burst through the doors as they opened. He leapt to the deserted platform, a slab of concrete in a burned-out neighborhood. The fair-haired boy was still staggering to get to his feet, furious. The girl dodged around him, and ran out of the dragon’s belly, an escaping yellow flame. Surprisingly, she didn’t stop to call for help. She just ran.

That was odd. Cursing, the fair-haired one regained his feet, looked after her and felt his blood stir to the chase. He sped across the platform after the fleeing form of the girl.

Greasy streetlights looming above in the humid night. Trash crushed in all the crevices of the broken concrete. No one around in the artificial light pools. Nocturnal creatures or nocturnal scavengers moving from shadow to shadow. A bleach-blond boy easily trailing a yellow cowslip girl, whose footsteps hammered to the beat of the cacophony of hidden nightlife, looking for someplace to hide.

His big pal joined him from out of a narrow alley, grabbing at his arm. “What’re you doing?” he hissed, jogging to keep up with the other’s smooth lope.

The fair one didn’t even bother to answer, his eyes fixed on his prey. The girl had paused at a corner and looked around, breathing hard. She saw them, and darted down another street.

“She’s not from this part of town. She’s gotta be lost. She can’t go anywhere,” the fair one said, by way of explanation. He ran on, pulse racing. His companion followed.

Down beneath the train tracks, the dragon’s skeletal feet, she ran, crossing a street, in and out of crosshatched shadows. Past a string of closed and barred and spray-painted stores—pawnshops, long-distance phone places, drug stores—

She had to be slowing down soon, the fair one figured. Soon she would be too disoriented and too beat to go much further…

Unexpectedly she halted and took off in a new direction, as though inspired.

They could see the girl was staggering now. A faint flickering figure with not much left in her... The two boys ran on, feeling sure that they were closing in. They wore sneakers, were used to racing for their lives.

Then the fair boy saw the church. It loomed in front of them, a gray-slabbed old mausoleum of heavy oak doors and a huge round window like a black spoked wheel that seemed to float ominously above their heads. The fair boy actually paused, but his pal, now intent on their goal, jerked him onward.

Ahead, the girl was running, stumbling, yanking at the neckline of her dress. She was hurrying up the steps; she was jamming something into the lock...

The fair one had seen that move before, a lady they had mugged shoving her car keys into the lock of her car, leaping in to make an escape…But this was a church, he thought. What sort of girl kept keys to a church?

Incredulous, the boys watched the door open,

swallow the yellow and white and black figure, and close, like a mouth obstinately shut.

Cursing out of sheer disbelief, the boys jumped up the steps and seized the door handles. Locked. Neither door would budge.

“She’s gone.”

They hardly knew which had spoken. It was like a drug haze. Around them, the City continued in its dead sounds of machines and boom-box music sliding in and out of the streets, in and out of consciousness.

The bleach blond stared and finally turned to his friend. “Did we just follow a girl out here?”

“We swiped her purse.” He tugged at the zipper of his jacket.

The church stood silent before them, betraying no secrets. No echo issued from beyond its walls.

At last, the older boy shook his head. “Some kind of weird. Like it never happened.”

“But it did. Lookit!” the big boy had fished out the purse, unzipped it, and thrust it at his older companion.

A mass of hundred dollar bills stared out at them. Gingerly, the fair-headed boy touched one as though it were enchanted. But it was real, thick green and white paper beneath his fingers. This was something they understood.

They didn’t know how or why a girl would come to be carrying thousands of dollars of cash in her purse in a subway late at night. And they didn’t care. The important thing now was to move quickly, before she could call the police. Once again, in unspoken unity, the boys wheeled away from the door—their astonishment already forgotten in the hurry to get to a safe place to gloat over their treasure.

The church stood a silent soldier against the slow destruction of the night.

II

Brother Leon whistled softly to himself as he strode down the corridor in his bare feet after morning Mass. It was Sunday, and today it was his job to make breakfast for the six other hungry men in the friary, who would soon be finishing morning prayers.

Swinging the heavy knotted rope he wore as a belt, he loped into the kitchen with an easy stride and swung the refrigerator door open. Out on one hand came a box of cracked eggs, on the other dangled half a loaf of bread and a gallon of milk. Sliding them all onto the chipped linoleum counter, he flipped open the freezer door and flung out a squashed frozen orange juice, catching it in his other hand as though it were a basketball.

Still whistling that morning’s hymn, “All Hail the Power of Jesus’ Name,” he twisted the dial on the stove to “medium-high,” slid the frying pan from the shelf to the burner, daubed in a hunk of margarine, and began cracking the eggs into the soon-sizzling pan and tossing the shells into the sink in syncopation, so that the hymn sounded like the bridge to a rap song.

Brother Leon’s eyes and hair were dark; his skin was a warm brown, the result of a happy marriage between a Puerto Rican and a Jamaican. He was short and wiry. Like the other friars of the community, he kept his head shaved Marine recruit style, but he wasn’t able to match their full beards. As he scratched the itchy fuzz that was all the beard he had been able to grow, he discarded the last shell, chucking it over his shoulder from halfway across the kitchen as he went to get a lid. He knew, without looking, that he had made it. Years of basketball gave you that sort of intuition.

Speeding up the rhythm of his whistling, he scrambled the eggs till they were fluffy. Stove off. Lid on top. Pam! OJ in the pitcher, water on. Stir. Sloshing orange juice and water until the liquid deepened to a golden whirlpool, he ended the vigorous exercise with a tap of the wooden spoon on the counter and tossed it over his back into the sink. This time, his throw was off. He heard the spoon glance from the counter to the floor and sighed.

Shrugging, he headed for the refectory with the breakfast. From the corridor came the slap of bare feet and sandals and the vocalizations of six men hoping for coffee and eggs.

Coffee! Leon slapped himself on the forehead as he set down the food on the pine plywood refectory table. Leon, how could you forget again? Groaning, he turned back to the kitchen, only to see the ancient coffee maker sputtering out a stream of brown brew. Brother Matt, glass coffeepot in hand, was gathering the precious drops in a mug.

“What the—” Leon shook his head, bewildered. “I could have sworn I forgot to do that!”

“You did,” Matt set the pot down calmly, smiling through his curly blond beard. “Typically, morning people like yourself who don’t need a drug to wake them up forget about making coffee.”

“Whew!” Leon heaved a sigh. “Well, thanks—you saved my skin. If I forget again, I’m sure Father Francis is going to write flogging back into the Franciscan constitutions!”

“Probably,” Matt grinned, his blue eyes snapping. The head of the order was notably short-tempered where his coffee was concerned. “I have to admit there was a less charitable motive behind my making coffee for you.”

“What’s that?” Leon rummaged through the drawers, piling spoons, forks, knives, and plates into his arms.

“There are two kinds of religious brothers in the world, Leon. Those who can make coffee, and those who can’t. I’m sorry to have to tell you which category you’re in.”

“Hey, I haven’t attained my earthly perfection yet. That’s why I’m here. But thanks all the same, Matt.”

“Any time,” Brother Matt looped his cord over his arm and carried the coffeepot and his own share out to the refectory where the other brothers were taking their seats.

Leon halted in the doorway as Father Bernard, the lithe dark-haired friar who was the resident mystic, murmured a blessing over the meal and the cook. After the fervent “Amens,” Leon stepped forward and began hurriedly to pass out the plates and silverware.

“Sorry, there’s no toast yet,” he apologized. “It’s coming.”

“Who has the margarine?” Father Francis peered round the table over his coffee cup, his bushy grey brows twitching.

“Coming!” Leon quickly left and re-emerged with a plate piled high with toasted bread and the tub of cheap margarine. The eggs had already mostly vanished from the pan, and the toast quickly dispersed throughout the gray-robed crowd. Leon took one last look around and then pulled back his chair with a sigh. There was a sizable garbage bag on it.

“What’s this?”

Brother Herman, a portly older friar who looked like Santa Claus on vacation, wrinkled his forehead. “I forgot. Clothes donation. I meant to bring it to storage last night. Here, I’ll get it.”

Despite the twitches of irritation that ran through his innards, Leon heaved the bag on to his shoulders. “Naah, I’ll get it. I’m up.” Sighing inwardly, he heaved the bag on to his shoulders and went out the door.

Religious life was filled with little frustrations like this one. You had to learn to live with the shortcomings of other men. Besides, he reflected as he ambled down the corridor, this can be my penance for forgetting to make coffee again.

Ah, who said that loving your neighbor was easy, anyhow? He swung into the small hallway that connected their house, an old rectory, with the church. The temporary clothes storage room was the vestibule of old St. Lawrence Church. It was packed with garbage bags stuffed with coats, shoes, socks, and underwear that generous families from six parishes had donated to the homeless. Someone ought to organize this room, Leon scowled as he looked around in the dim light for a bare place to stick the new bag. Well, at least someone had started to sort out the men’s jackets into a pile on the floor.

Then Leon froze, his jaw dropping.

When he recovered, he spun on his heel, and darted back into the hallway. Luckily, Father Bernard had already left the table and was in the hall, talking quietly to Brother Matt. Leon caught Father’s eye and motioned in bewilderment. Nodding to the other brother, the priest came down the hall, his gray habit billowing behind.

“What is it, Leon?” Father scrutinized Leon’s face.

Leon led him into the storage room without a word and pointed.

Brother Charley was lumbering by, having come from answering the doorbell. Big, burly, and slow, he had led a wild l

ife long enough to have a nose for trouble. He followed the other two friars into the storage room, towering over them. “What’s up?” he asked, and then his eyes widened as he saw.

There’s something about the atmosphere of a small friary that speeds up communication. As Brother Leon hurried up the passage to get Father Francis, he nearly bumped into Brother Herman, who was apparently seized by curiosity at the furtive movements of his brothers.

“Something going on?” the older friar asked confidentially.

“Just a crisis—in the storage room,” Leon inched around him.

“Another rat colony?” Brother Herman’s face wrinkled into a grimace as he glanced at Matt. “We’ll have to get out the slingshots.” The rats of the South Bronx were legendary in size, and the friars had been waging an unsuccessful war against them for possession of the church and friary.

“Uh—Father!” Leon waved at Father Francis, who was still nursing his coffee cup at the table.

A few moments later, Leon was leading Father Francis back to the storeroom. Charley was still there, squatting before the lump in the corner. Herman and Matt were trying to get a better view. In front of them, Father Bernard looked clearly lost. The whole community was gathered in the vestibule now—even reclusive Brother George had left his chores to peer around the doorjamb. The silence was almost funereal.

“All right, move aside. Who said we needed group support here?” Father Francis said, elbowing his fellow friars aside. Brother Leon saw Father Francis’s bushy white brows shoot up his wrinkled forehead as he saw the object: a slim, white ankle nestled on the sleeve of a jacket. “Heaven help us,” the community’s founder muttered, and Leon knew they were both thinking the same thing—that someone had dumped a body in their friary. He could see the headlines now: BODY OF YOUNG WOMAN FOUND IN FRIARY. POLICE FILE MURDER CHARGES. “Just what we need,” Leon murmured to himself, sweating slightly.

Brother Herman was frowning. He had edged closer to the pile of coats and was leaning his chubby frame over the body; turning his red, round face this way and that. Finally, he leaned back heavily with a sigh. “I think she’s just sleeping,” he said in a stage whisper to Father Francis.