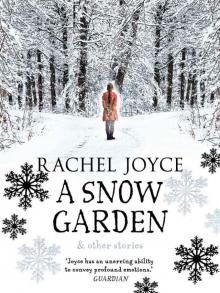

A Snow Garden and Other Stories

Rachel Joyce

About the Book

In the course of a fortnight at the end of a year . . . a woman finds a cure for a broken heart where she least expects it; a husband and wife build their son a bicycle and, in the process, deconstruct their happy marriage; freak weather brings the airport to a standstill on Christmas Day; a young woman will change her life by saying one word.

Here are seven linked stories. Each of them is a small masterpiece, but as one character steps forward and another steps back, it is in the way they interweave that Rachel Joyce pinpoints much of the humour and tragedy of our everyday experience.

With hallmarks that made her first book, The Unlikely Pilgrimage of Harold Fry, so exceptional, A Snow Garden & other stories celebrates heroism in the most unassuming of figures and finds significance in small moments that can change everything. Compelling and rewarding, tender and funny, it portrays family relationships at a time of year that should be joyous but is so often tangled and painful, reminding us that there is always a bigger story behind the one we first see.

Contents

Cover

About the Book

Title Page

Dedication

Foreword

Epigraph

A Faraway Smell of Lemon

The Marriage Manual

Christmas Day at the Airport

The Boxing Day Ball

A Snow Garden

I’ll Be Home for Christmas

Trees

About the Author

Also by Rachel Joyce

Copyright

A Snow Garden

and Other Stories

Rachel Joyce

For Kezia May, because you always liked a short story.

Foreword

There is a joke I like about an actress playing the nurse in Romeo and Juliet. Someone asks her what the play is about.

Now the nurse is a nice part for an older woman. She gets a few laughs. She’s seen a thing or two and she voices the things the audience longs to hear – so we like her. But let’s face it, she only has a few scenes and she’s not Juliet. She probably gets one costume and the chances are it’s a tabard, along with some sort of uncomfortable and slightly insane-looking headdress, a thing with horns and a veil.

Anyway, the actress thinks very carefully about how best to summarize the plot of Romeo and Juliet and then she says, ‘Well, it’s all about this nurse …’

We are at the centre of our own stories. And sometimes it is hard to believe that we are not at the centre of other people’s. But I love the fact that you can brush past a person with your own story, your own life, so big in your mind and at the same time be a simple passer-by in someone else’s. A walk-on part.

Like most things, this book did not end up as the thing it began as. It was meant to be three stories. (It’s seven.) They were not meant to be linked. (They are.) It was meant to be a comparatively small, quick project. (It wasn’t.)

When I write – whether it’s fiction or plays, and even when I adapt other people’s novels for radio – I make lots of cuts. Words go. Descriptions go. Passages. Chapters. And sometimes, yes, entire characters. As much as I may like those words or descriptions or characters, if they are holding up the story and getting in its way, they end up being deleted. And this is why I have the idea of my caravan (where I write) being stuffed with people I have cut from my writing. Binny, for example, who is the main character in the first story of this collection, was no more than an extra in an early draft of my second novel Perfect, but she was too big for the book and threatened to over-topple it. Very reluctantly I cut her. Henry, who ‘lives’ in the title story, was originally a rehearsal for a character in the new novel I’m working on called The Music Shop. Alan and Alice, the married couple in the second story, were once in an afternoon play and had ambitions for bigger things – a film maybe, but that never happened. Then there is a story about a young woman called Maureen going to a local dance, and while I kept her in The Unlikely Pilgrimage of Harold Fry, I couldn’t keep the story of how her life changed that night. Sometimes I picture all these ‘cut’ characters stuffed in my caravan, making a nuisance of themselves, and the racket is quite something. So I loved the idea that I could clean them out, as it were, by giving each of them a short story of their own.

(I still have a batch of curates that I had to delete when I was dramatizing Charlotte Brontë’s Shirley for BBC Radio 4. They spend entire days in my caravan gossiping and drinking tea, and I have no idea what I am going to do with them. If you would like to adopt them, they are available.)

Stories are important. We need them. It is through telling and hearing stories that we make sense of the world. Like dreams, they come to us when we are quiet and they tell us something or remind us of something that we need to hear. They say to us, No, you’re not alone. Because that thing you feel, I feel it too. And sometimes they ask us to think again.

The appeal for me of a short story is that it is like a dream and it is like life; a curtain sweeps open briefly and at a key point in someone’s history you are allowed to sit so close you can see the creases, the dimples and the freckles of their skin, and then – whoosh – the curtain closes and they have gone.

A society grows great when old men plant trees whose shade they know they will never sit in.

Greek proverb

A Faraway Smell of Lemon

It is half past nine and Oliver will be eating porridge in his Asterix bowl. At the age of thirty-three he has no regular habits but these – the porridge and the bowl – and he is faithful to both.

‘Sod him,’ Binny snorts, striding into the morning traffic. Pavements jostle with Christmas shoppers. The city streets are dull beneath the December cloud and when the sun breaks through it is white as the moon. A giant billboard shows an image of a pretty young woman in a 1960s-style red coat looking up at snow. Shop windows twinkle with lights and tinsel decorations and illuminated messages wishing good will to all men. ‘Sod him,’ Binny repeats. No, no, no. She will not cry.

Now that she has dropped off the children at school for their last day of term, Binny has five hours to fix Christmas. As a girl, she was brought up by her parents to love it – the parties, the food, the presents, the decorations – but this year she has done nothing. She hasn’t bought a tree (they don’t need one). She hasn’t ordered a turkey (they’ll never finish it). She hasn’t posted cards to any of the people who have sent her cards and neither has she bought presents or tubes of metallic gift-wrap. This morning, Coco pinned two large woollen slipper socks above the mantelpiece for herself and Luke. (‘Just so we don’t forget on the day,’ she said.) If only the machine that is Christmas would come and go without Binny.

She spots one of the school mothers jogging towards her like an aerobic fairy. Binny freezes, searching for an escape, but she is not the sort of person who can easily hide.

Tall and broad, Binny towers over other people, even if she stoops. And she does, she does it all the time, she is always stooping and slouching and digging her hands into her pockets in an attempt to make herself lesser. She is dressed, as always, in something black and shapeless she found tangled on the end of her foot this morning as she staggered towards the bathroom.

The jogging mother does not look like the sort of person who wears screwed-up versions of what she had on the day before. She wears a candy-pink jogging suit with a fur trim. She is something to do with the school PTA, but Binny can’t for the life of her remember what, because Binny never opens the emails and she never attends the functions. If she stands very still – if she pretends that she is not here – maybe the woman will bounce along and not notice her.

‘Binny!’ the happy jogging suit call

s. ‘Hiya!’ She shouts something that might be about the Nativity play but a double-decker bus roars past. The advertisement with the young woman in her red coat seems to be all over that too.

The Nativity play will be performed this afternoon. Only it is not a Nativity play, as the children keep reminding her, it is a Winter Celebration. It was just last night, as he climbed into bed, that Luke revealed he was playing the part of Larry the Lizard. ‘But there was no lizard in the Nativity,’ said Binny. ‘This isn’t the Nativity,’ sighed Luke. And Coco added, ‘Our headmistress says the Nativity is not multicultural and also there are no parts for girls. Except Mary.’ ‘But there’s no lizard in any religious festival,’ said Binny. ‘Larry the Lizard is Buzz Lightyear’s friend,’ said Luke. ‘What?’ said Binny. ‘Buzz Lightyear has nothing to do with Christmas! You never see him in any Christmas scene!’ And Coco said, ‘Well, Larry is very significant. He sings the solo from Frozen. Also, I am the Ghost of Christmas Past.’ When Binny complained that it was no good, she couldn’t run up a lizard costume at the drop of a hat, no one could, and actually the Ghost of Christmas Past was in another bloody story altogether, by Charles Dickens, as it happens, Coco and Luke had exchanged a small but solemn nod. ‘It’s all right, Mum,’ said Coco gently. ‘Meera’s mum made our costumes. Luke has a blue tail with spikes and everything. I am going to have a lamp and a fur hat and also a sari.’ Coco seemed more than happy about that. She didn’t mind at all.

Binny did mind. She minded very much. She wanted to be a good mother, but here were all these others, being not just good mothers but super-mothers. Did Charles Dickens realize, all those years ago, as he wrote about snow scenes and Christmas spirits, not to mention roast goose and country-dancing, what he had gone and started? Was it not hard enough trying to bring up two children and work part-time, without having to stage an annual Christmas pageant as well?

The jogging suit is so close there is no hope of escape. There will have to be a conversation and the jogging suit will ask if Binny is all sorted for Christmas, and How is Oliver? and Isn’t he nice? and Binny will want to scream. No, she is not all sorted. Her heart has been broken. Snapped in two. What is the point of Christmas? What she really wants is to deal the blow as brutally as it was landed on her, and to watch someone else reel and give in to the tide of grief that Binny herself will not allow.

Instead she slams her hand to her head to suggest that she has just remembered something crucial – a last-minute piece of shopping, such as the turkey, for instance – and bounds towards the nearest shop. The fresh cuts on her hands sting like tiny prickles as she pushes open the door.

It is as if Binny has stepped through a curtain and discovered an alternative universe. It’s been here for ever, this shop, but she’s never bothered to come inside, just as she’s never bothered with the boutique next door that sells party frocks and wedding dresses. For a moment she stands very still in this strange, new place where the dust swirls like glitter. The silence is unearthly. There are shelves and shelves of cleaning products. They come in jars, canisters and bottles, some plastic, some glass, all arranged at regular intervals and in order of size. There are displays of brushes, cloths, scourers, dusters – both the feathered and the yellow variety. There are boxes of gloves – heavy-duty, latex, nitrile, polythene – as well as Kentucky mops, squeegees, litter-pickers and brooms. Binny had no idea that cleaning could be so complicated. Right beside the till stands a small plastic angel, the only clue as to the time of year. She has a halo and a crinkly white dress and two pointed tinsel wings. There is a smell Binny can’t put a name to, but it makes her think of lemon peel. Clearly there is nothing here for a woman like herself.

She is about to retreat when a female voice chimes through the silence, ‘Can I help?’

Binny squints in the direction of the voice and sees a slight young woman gliding towards her. Her skin is a flawless ivory and her deep-brown eyes are like seeds, as if she is studying Binny from inside a porcelain mask. She must be in her early twenties. She wears a crisp uniform that suggests a dentist’s but surely can’t be, and her black hair is caught in a polished ponytail. The young woman stands with her hands at her side and her crepe-soled shoes not quite touching, as if physical untidiness would be offensive.

At the age of ten, Coco is the only one in Binny’s house who understands tidiness. Luke does not understand it (because, he says, he’s only eight) and Binny doesn’t understand it either, although she is forty-seven. The daughter of a naval officer and a girdled socialite who had people ‘who did’, Binny has made a point of embracing chaos. Her home is bound in a thicket of ivy. The small rooms are so packed with her parents’ Victorian furniture (‘Junk,’ Oliver calls – no, called – it) that most of them have been reduced to passageways. Surfaces are felted with dust and piled high with old magazines and newspapers and tax returns and letters she has never bothered to answer. The carpet is thick with dust balls the size of candyfloss, screwed-up clothes on their way to the washing machine and nuggets of Lego, and in the middle of the sitting room there is a dead shrub that the children have been using for a Christmas tree. They have decorated it with cut-out paper snowmen and pigeon feathers and brightly coloured sweet wrappers.

‘Don’t you sell stuff for someone like me?’ asks Binny. ‘Paracetamol or coffee or something?’

The young woman is curt. Not exactly rude, but she isn’t friendly. ‘This is a family business. We’ve never sold anything but cleaning products. We supply mainly to hotels. And also corporate catering.’

Binny examines the bottles that gleam from the top shelves like coloured eyes. Keep out of the reach of small children. Phosphoric acid. Benzyl salicylate. If swallowed DO NOT INDUCE VOMITING. ‘Is this stuff legal?’

‘We don’t sell a product if we can’t guarantee it will work. We are not like those supermarkets where the bleach you buy is water. For instance, some bathroom cleaners are specifically for shower tiles and some react badly with the grouting. You have to take these things into account.’

‘I suppose you do. I don’t have a shower. At least, I do, but it has no door. And the water doesn’t shower. It sort of dumps on you.’

‘That’s a shame,’ the young woman says.

‘It is,’ agrees Binny.

‘You should get it fixed.’

‘I won’t, though.’

The shower is one of the things Oliver has spent the last three years promising to mend. The Hoover is another. Oliver is messy-haired, easy-going, slightly fuzzy at the edges, always wearing his T-shirt inside out and socks that don’t match. He can spend minutes untangling loose change from his trouser pocket for anyone who happens to hold out a hand and ask for it. The rest of the time he is so busy gazing at the sky that Binny has long suspected he will one day flap his arms and soar upwards.

It never used to matter that Oliver was a good twelve years younger than Binny and had no regular income because he was an actor who couldn’t get what he called ‘proper acting work’, only voice-overs or the odd commercial. It never used to matter that he always left the keys to the van in the driver’s door and forgot about things like replacing toilet rolls. It never used to matter that he might go to fix the shower and notice his reflection in the bathroom mirror and drift straight back to the kitchen to ask Binny if she had some concealer because he was afraid he might have a spot coming.

But their loving had become commonplace. They had stopped noticing the otherness of one another and now that otherness was no longer a source of wonder but instead an irritation. Binny cussed every time she walked into his guitar at the foot of the bed. Or, ‘Why must you always use the moisturizer?’ she’d complain. ‘I didn’t think you’d mind, Bin.’ ‘I mind because you never replace it and you always leave the lid off.’ ‘Well, I won’t use it then,’ he would shrug. ‘But if it were mine, I’d just share.’ He would wander upstairs to play his guitar, leaving her even grouchier because now she felt not only disgruntled but also less generous th

an him. Playing his guitar was what Oliver did when he was sad. His songs offered an escape to a land where girls had long hair and wept over Irish seas. They were beautiful in their way, even if they were childlike.

However, the shop woman is still talking. She is still on cleaning fluids. ‘Of course, you can’t use some materials on plastic. Or carpets. Even lino you must be careful with. You have to match the product to the problem.’

This is anathema to Binny. Surely there is clean or not clean? And in her house there is only the latter. She tries to find a new point of contact. ‘Where I live, there’s a smell. I don’t know what it’s of. It’s been there years.’

‘Drains?’ Despite herself, the assistant looks very interested.

‘No. It’s more like … old things. The past. You get it differently in different parts of the house. For instance, upstairs, just outside the loo, I can definitely smell my ex-husband’s aftershave and we divorced six years ago. Or other times I’ll get this overwhelming scent of my mother’s jasmine soap. Then there was a friend I had once when I was a girl. She was a few years younger than me but we did everything together, and then she got married after university and we lost touch. I still get a whiff of her rose-oil perfume once in a while. Do you think the memory of a smell can hang about in a room? Would you have anything for that?’

‘For the memory of a smell?’ The assistant frowns.

‘No, of course you don’t. Basically the house is covered in shit.’

‘Is this connected to the smell?’

‘Metaphorical shit.’ Binny laughs. She regrets it instantly. It sounds like the sort of thing her ex-husband used to say. It sounds as if she thinks she’s clever.

Her intelligence is not something she likes to flaunt. It’s the same with her body, and also her feelings. When her mother died a few years ago, hot on the heels of her father, Binny refused to cry. ‘You must let go,’ her friends urged. ‘You must grieve.’ She wouldn’t, though. To cry was to acknowledge that something was well and truly over. Besides, given the size of her, it felt dangerous. She might swamp the world. Instead she stopped seeing her friends.