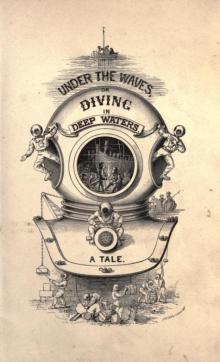

Under the Waves: Diving in Deep Waters

R. M. Ballantyne

Produced by Nick Hodson of London, England

Under the Waves; or, Diving in Deep Waters, by R.M.Ballantyne.

________________________________________________________________________

This was a very difficult book to obtain. There was a copy in theBritish Library, and another one in a Library in Dartmouth, Devon. Forseveral years I tried at least weekly to find a copy via Abebooks oreBay, with no success. The copy belonging to the Ballantyne family haddisappeared, not to put too fine a point on it. Eventually a kindfamily in Canada offered to scan the pages of their copy, and send theimages to me, and this is the result.

Ballantyne did indeed try out some diving equipment, so as to obtain afirst-hand feel for diving. It is related that something went wrong, toomuch air was sent down, and he surfaced rapidly upside down. A similarepisode is related in the book.

Ballantyne's style often gives rise to two or even three storiescontinuing simultaneously, and here we have the adventures of one RooneyMachowl, an Irishman who decides to move from his ship's carpenter tradeto that of diving. In fact divers should always have another trade, orthey wouldn't be much use under the water. In addition there is theaspiration of Edgar Berrington to win the hand of a fair young lady,there are the events happening to the young lady's father, and thenagain the events happening to the young lady's companion. So it is allfairly convoluted. But you'll certainly learn a lot about diving, asthe art stood in 1876. It is rather strange that Ballantyne, havingwritten this book, which ran to several printings, did not much mentiondiving in any other of his books.

________________________________________________________________________

UNDER THE WAVES; OR, DIVING IN DEEP WATERS, BY R.M.BALLANTYNE.

PREFACE.

This tale makes no claim to the character of an exhaustive illustrationof all that belongs to the art of diving. It merely deals with the mostimportant points, and some of the most interesting incidents connectedtherewith. In writing it I have sought carefully to exhibit the trueand to ignore the false or improbable.

I have to acknowledge myself indebted to the well-known submarineengineers Messrs. Siebe and Gorman, and Messrs. Heinke and Davis, ofLondon, for much valuable information; and to Messrs. Denayrouze, ofParis, for permitting me to go under water in one of theirdiving-dresses. Also--among many others--to Captain John Hewat,formerly Commander in the service of the Rajah of Sarawak, for muchinteresting material respecting the pirates of the Eastern Seas.

R.M.B. Edinburgh, 1876.

CHAPTER ONE.

INTRODUCES OUR HERO, ONE OF HIS ADVISERS, AND SOME OF HIS DIFFICULTIES.

"So, sir, it seems that you've set your heart on learning something ofeverything?"

The man who said this was a tall and rugged professional diver. He towhom it was said was Edgar Berrington, our hero, a strapping youth oftwenty-one.

"Well--yes, I have set my heart upon something of that sort, Baldwin,"answered the youth. "You see, I hold that an engineer ought to bepractically acquainted, more or less, with everything that bears, evenremotely, on his profession; therefore I have come to you for someinstruction in the noble art of diving."

"You've come to the right shop, Mister Edgar," replied Baldwin, with agratified look. "I taught you to swim when you wasn't much bigger thana marlinespike, an' to make boats a'most before you could handle aclasp-knife without cuttin' your fingers, an' now that you've come toman's estate nothin'll please me more than to make a diver of you.But," continued Baldwin, while a shade clouded his wrinkled andweatherbeaten visage, "I can't let you go down in the dress withoutleave. I'm under authority, you know, and durstn't overstep--"

"Don't let that trouble you," interrupted his companion, drawing aletter from his pocket; "I had anticipated that difficulty, and wrote toyour employers. Here is their answer, granting me permission to usetheir dresses."

"All right, sir," said Baldwin, returning the letter without looking atit; "I'll take your word for it, sir, as it's not much in my line tomake out the meanin' o' pot-hooks and hangers.--Now, then, when will youhave your first lesson?"

"The sooner the better."

"Just so," said the diver, looking about him with a thoughtful air.

The apartment in which the man and the youth conversed was a species ofout-house or lumber-room which had been selected by Baldwin for thestowing away of his diving apparatus and stores while these were not inuse at the new pier which was in process of erection in the neighbouringharbour. Its floor was littered with snaky coils of india-rubbertubing; enormous boots with leaden soles upwards of an inch thick;several diving helmets, two of which were of brightly polished metal,while the others were more or less battered, dulled, and dinted by hardservice in the deep. The walls were adorned with large dampindia-rubber dresses, which suggested the idea of baby-giants who hadfallen into the water and been sent off to bed while their costumes werehung up to dry. In one corner lay several of the massive breast andback weights by which divers manage to sink themselves to the bottom ofthe sea; in another stood the chest containing the air-pump by means ofwhich they are enabled to maintain themselves alive in thatuncomfortable position; while in a third and very dark corner, an oldworn-out helmet, catching a gleam from the solitary window by which theplace was insufficiently lighted, seemed to glare enviously out of itsgoggle-eyes at its glittering successors. Altogether, what with thestrange spectral objects and the dim light, there was something weird inthe aspect of the place, that accorded well with the spirit of youngBerrington, who, being a hero and twenty-one, was naturally romantic.

But let us pause here to assert that he was also practical--eminentlyso. Practicality is compatible with romance as well as with rascality.If we be right in holding that romance is gushing enthusiasm, then arewe entitled to hold that many methodical and practical men have been,are, and ever will be, romantic. Time sobers their enthusiasm a little,no doubt, but does by no means abate it, unless the object on which itis expended be unworthy.

Recovering from his thoughtful air, and repeating "Just so," the diveradded, "Well, I suppose we'd better begin wi' them 'ere odds an' endsabout us."

"Not so," returned the youth quickly; "I have often seen the apparatus,and am quite familiar with it. Let us rather go to the pier at once.I'm anxious to go down."

"Ah! Mister Edgar--hasty as usual," said Baldwin, shaking his headslowly. "It's two years since I last saw you, and I _had_ hoped to findthat time had quieted you a bit, but--. Well, well--now, look here: youthink you've seen all my apparatus, an' know all about it?"

"Not exactly all," returned the youth, with a smile; "but you know I'veoften been in this store of yours, and heard you enlarge on most if notall of the things in it."

"Yes--most, but not _all_, that's where it lies, sir. You've often seenSiebe and Gorman's dresses, but did you ever see this helmet made byHeinke and Davis?"

"No, I don't think I ever did."

"Or that noo helmet wi' the speakin'-toobe made by Denayrouze andCompany, an' this dress made by the same?"

"No, I've seen none of these things, and certainly this is the firsttime I have heard of a speaking-tube for divers."

"Well then, you see, Mister Edgar, you have something to larn here afterall; among other things, that Denayrouze's is _not_ the firstspeakin'-toobe," said Baldwin, who thereupon proceeded with the mostimpressive manner and earnest voice to explain minutely to his no lessearnest pupil the various clever contrivances by which the severalmakers sought to render their apparatus perfect.

With all this, however, we will not trouble the reader, but proceed atonce to the port, where diving operations were being carried on inconnection with re

pairs to the breakwater.

On their way thither the diver and his young companion continued theirconversation.

"Which of the various dresses do you think the best?" asked Edgar.

"I don't know," answered Baldwin.

"Ah, then you are not bigotedly attached to that of your employer--likesome of your fraternity with whom I have conversed?"

"I _am_ attached to Siebe and Gorman's dress," returned Baldwin, "but Iam no bigot. I believe in every thing and every creature having goodand bad points. The dress I wear and the apparatus I work seem to me asnear perfection as may be, but I've lived too long in this world tosuppose nobody can improve on 'em. I've heard men who go down in thedresses of other makers praise 'em just as much as I do mine, an' maybewith as good reason. I believe 'em all to be serviceable. When I'vehad more experience of 'em I'll be able to say which I think the best.--I've got a noo hand on to-day," continued Baldwin, "an' as he's goin'down this afternoon for the first time, so you've come at a good time.He's a smart young man, but I'm not very hopeful of him, for he's anIrishman."

"Come, old fellow," said Edgar, with a laugh, "mind what you say aboutIrishmen. I've got a dash of Irish blood in me through my mother, andwon't hear her countrymen spoken of with disrespect. Why should not anIrishman make a good diver?"

"Because he's too excitable, as a rule," replied Baldwin. "You see,Mister Edgar, it takes a cool, quiet, collected sort of man to make agood diver, and Irishmen ain't so cool as I should wish. Englishmen arebetter, but the best of all are Scotchmen. Give me a good, heavy,raw-boned lump of a Scotchman, who'll believe nothin' till he'sconvinced, and accept nothin' till it's proved, who'll argue with astone wall, if he's got nobody else to dispute with, in that slow sedatehumdrum way that drives everybody wild but himself, who's got an amazin'conscience, but no nerves whatever to speak of--ah, that's the man to gounder water, an' crawl about by the hour among mud and wreckage withoutgittin' excited or makin' a fuss about it if he should get his life-lineor air-toobe entangled among iron bolts, smashed-up timbers, twistedwire-ropes, or such like."

"Scotchmen should feel complimented by your opinion of them," saidEdgar.

"So they should, for I mean it," replied Baldwin, "but I hope theIrishman will turn up a trump this time.--May I take the liberty ofaskin' how you're gittin' on wi' the engineering, Mister Edgar?"

"Oh, famously. That is to say, I've just finished my engagement withthe firm of Steel, Bolt, Hardy, and Company, and am now on the point ofgoing to sea."

Baldwin looked at his companion in surprise. "Going to sea!" herepeated, "why, I thought you didn't like the sea?"

"You thought right, Baldwin, but men are sometimes under the necessityof submitting to what they don't like. I have no love for the sea,except, indeed, as a beautiful object to be admired from the shore, but,you see, I want to finish my education by going a voyage as one of thesubordinate engineers in an ocean-steamer, so as to get some practicalacquaintance with marine engineering. Besides, I have taken a fancy tosee something of foreign parts before settling down vigorously to myprofession, and--"

"Well?" said Baldwin, as the youth made rather a long pause.

"Can you keep a secret, Baldwin, and give advice to a fellow who standssorely in need of it?"

The youth said this so earnestly that the huge diver, who was asympathetic soul, declared with much fervour that he could do both.

"You must know, then," began Edgar with some hesitation, "the fact is--you're such an old friend, Baldwin, and took such care of me when I wasa boy up to that sad time when I lost my father, and you lost anemployer--"

"Ay, the best master I ever had," interrupted the diver.

"That--that I think I may trust you; in short, Baldwin, I'm over headand ears with a young girl, and--and--"

"An' your love ain't requited--eh?" said Baldwin interrogatively, whilehis weatherbeaten face elongated.

"No, not exactly that," rejoined Edgar, with a laugh. "Aileen loves mealmost, I believe, as well as I love her, but her father is dead againstus. He scorns me because I am not a man of wealth."

"What is _he_?" demanded Baldwin.

"A rich China merchant."

"He's more than that," said Baldwin.

"Indeed!" said Edgar, with a surprised look; "what more is he?"

"He's a goose!" returned the diver stoutly.

"Don't be too hard on him, Baldwin. Remember, I hope some day to callhim father-in-law. But why do you hold so low an opinion of him?"

"Why, because he forgets that riches may, and often do, take tothemselves wings and fly away, whereas broad shoulders, and deep chest,and sound limbs, and a good brain, usually last the better part of alifetime; and a brave heart will last for ever."

"I am afraid that I have yet to prove, to myself as well as to the oldgentleman, that the brave heart is mine," returned Edgar. "As to thephysique--you may be so far right, but he evidently undervalues that."

"I said nothing about physic," returned Baldwin, who still frowned as hethought of the China merchant, "and the less that you and I have to dowi' that the better. But what are you goin' to do, sir?"

"That is just the point on which I want to have your advice. What oughtI to do?"

"Don't run away with her, whatever you do," said Baldwin emphatically.

The youth laughed slightly as he explained that there was no chancewhatever of his doing that, because Aileen would never consent to runaway or to disobey her father.

"Good--good," said the diver, with still greater emphasis than before,"I like that. The gal that would sacrifice herself and her lover soonerthan disobey her father--even though he is a goose--is made o' the rightstuff. If it's not takin' too great a liberty, Mister Edgar, may I askwhat she's like?"

"What she's like--eh?" murmured the other, dropping his head as if inreverie, and stroking the dark shadow on his chin which was beginning todo duty for a beard. "Why, she--she's like nothing that I ever saw onearth before."

"No!" ejaculated Baldwin, elevating his eyebrows a little, as he saidgravely, "what, not even like an angel?"

"Well, yes; but even that does not sufficiently describe her. She'sfair,"--he waxed enthusiastic here,--"surpassingly fair, with wavygolden tresses and blue eyes, and a bright complexion and a winningvoice, and a sylph-like figure and a thinnish but remarkably prettyface--"

"Ah!" interrupted Baldwin, with a sigh, "I know: just like my missus."

"Why, my good fellow," cried Edgar, unable to restrain a fit oflaughter, "I do not wish to deny the good looks of Mrs Baldwin, but youknow that she's uncommonly ruddy and fat and heavy, as well as fair."

"Ay, an' forty, if you come to that," said the diver. "She's fourteenstun if she's an ounce; but let me tell you, Mister Edgar, she wasn'talways heavy. There _was_ a time when my Susan was as trim and taut andclipper-built as any Aileen that ever was born."

"I have no doubt of it whatever," returned the youth, "but I was goingto say, when you interrupted me, it is her eyes that are her strongpoint--her deep, liquid, melting blue eyes, that look at you soearnestly, and seem to pierce--"

"Ay, just so," interrupted the diver; "pierce into you like a gimblet,goin' slap agin the retina, turnin' short down the jugular, right intothe heart, where they create an agreeable sort o' fermentation. Oh!Don't I know?--my Susan all over!"

Edgar's amusement was tinged slightly with disgust at the diver'spersistent comparisons. However, mastering his feelings, he againdemanded advice as to what he should do in the circumstances.

"You han't told me the circumstances yet," said the diver quietly.

"Well, here they are. Old Mr Hazlit--"

"What! Hazlit? Miss Hazlit, is _that_ her name?" cried Baldwin, with alook of pleased surprise.

"Yes, do you know her?"

"Know her? Of course I do. Why, she visits the poor in my district o'the old town--you know I'm a local preacher among the Wesleyans--an'she's one o' the best an' sweetest--ha! Angel indeed! I'm glad she

wasn't made an angel of, for it would have bin the spoilin' of asplendid woman. Bless her!"

The diver spoke with much enthusiasm, and the young man smiled as hesaid, "Of course I add Amen to your last words.--Well then," hecontinued, "Aileen's father has refused to allow me to pay my addressesto his daughter. He has even forbidden me to enter his house, or tohold any intercourse whatever with her. This unhappy state of thingshas induced me to hasten my departure from England. My intention is togo abroad, make a fortune, and then return to claim my bride, for thewant of money is all that the old gentleman objects to. I cannot bearthe thought of going away without saying good-bye, but that seems nowunavoidable, for he has, as I have said, forbidden me the house."

Edgar looked anxiously at his companion's face, but received noencouragement there, for Baldwin kept his eyes on the ground, and shookhis head slowly.

"If the old gentleman has forbid you his house, of course you mustn't gointo it. However, it seems to me that you might cruise about the houseand watch till Sus--Aileen, I mean--comes out; but I don't myself quitelike the notion of that either, it don't seem fair an' above-boardlike."

"You are right," returned Edgar. "I cannot consent to hang about aman's door, like a thief waiting to pounce on his treasure when itopens. Besides, he has forbidden Aileen to hold any intercourse withme, and I know her dear nature too well to subject it to a uselessstruggle between duty and inclination. She is certain to obey herfather's orders at any cost."

"Then, sir," said Baldwin decidedly, "you'll just have to go afloatwithout sayin' good-bye. There's no help for it, but there's thiscomfort, that, bein' what she is, she'll like you all the better forit.--Now, here we are at the pier. Boat a-hoy-oy!"

In reply to the diver's hail a man in a punt waved his hand, and pulledfor the landing-place.

A few strokes of the oar soon placed them on the deck of a large clumsyvessel which lay anchored off the entrance to the harbour. This was thediver's barge, which exhibited a ponderous crane with a pendulous hookand chain in the place where its fore-mast should have been. Severalmen were busied about the deck, one of whom sat clothed in the fulldress of a diver, with the exception of the helmet, which was unscrewedand lay on the deck near his heavily-weighted feet. The dress was wet,and the man was enjoying a quiet pipe, from all which Edgar judged thathe was resting after a dive. Near to the plank on which the diver wasseated there stood the chest containing the air-pumps. It was open, thepumps were in working order, with two men standing by to work them.Coils of india-rubber tubing lay beside it. Elsewhere were strewn aboutstones for repairing the pier, and various building tools.

"Has Machowl come on board yet?" asked Baldwin, as he stepped on thedeck. "Ah, I see he has.--Well, Rooney lad, are you prepared to godown?"

"Yis, sur, I am."

Rooney Machowl, who stepped forward as he spoke, was a fine specimen ofa man, and would have done credit to any nationality. He was about themiddle height, very broad and muscular, and apparently twenty-threeyears of age. His countenance was open, good-humoured, andgood-looking, though by no means classic--the nose being turned-up, theeyes small and twinkling, and the mouth large.

"Have you ever seen anything of this sort before?" asked Baldwin, with amotion of his hand towards the diving apparatus scattered on the deck.

"No sur, nothin'."

"Was you bred to any trade?"

"Yis, sur, I'm a ship-carpenter."

"An' why don't you stick to that?"

"Bekase, sur, it won't stick to me. There's nothin' doin' apparently inthis poort. Annyhow I can't git work, an' I've a wife an' chick athome, who've bin so long used to praties and bacon that their stummicksdon't take kindly to fresh air fried in nothin'. So ye see, sur,findin' it difficult to make a livin' above ground, I'm disposed to tryto make it under water."

While Rooney Machowl was speaking Baldwin regarded him with a fixed andcritical gaze. What his opinion of the recruit was did not, however,appear on his countenance or in his reply, for he merely said, "Humph!Well, we'll see. You'll begin your education in your noo profession bypayin' partikler attention to all that is said an' done around you."

"Yis, sur," returned Machowl, respectfully touching the peak of his capand wrinkling his forehead very much, while he looked on at the furtherproceedings of the divers with that expression of deep earnest sincerityof attention which--whether assumed or genuine--is only possible to thecountenance of an Irishman.

During this colloquy the two men standing by the pump-case, and twoother men who appeared to be supernumeraries, listened with muchinterest, but the diver seated on the plank, resting and calmly smokinghis pipe, gazed with apparent indifference at the sea, from which he hadrecently emerged.

This man was a very large fellow, with a dark surly countenance--notexactly bad in expression, but rather ill-tempered-looking. Hisdiving-dress being necessarily very wide and baggy, made him seem largerthan he really was--indeed, quite gigantic. The dress was made of verythick india-rubber cloth, and all--feet, legs, body, and arms--was ofone piece, so perfectly secured at the seams as to be thoroughlyimpervious to air or water. To get into it was a matter of somedifficulty, the entrance being effected at the neck. When this neck isproperly attached to the helmet, the diver is thoroughly cut off fromthe external world, except through the air-tube communicating with hishelmet and the pump afore mentioned.

"Have ye got the hole finished, Maxwell?" said Baldwin, turning to thesurly diver.

"Yes," he replied shortly.

"Well, then, go down and fix the charge. Here it is," said Baldwin,taking from a wooden case an object about eighteen inches long, whichresembled a large office-ruler that had been coated thickly with pitch.It was an elongated shell filled to the muzzle with gunpowder. To oneend of it was fastened the end of a coil of wire which was also coatedwith some protecting substance.

As Baldwin spoke Maxwell slowly puffed the last "draw" from his lips andknocked the ashes out of his pipe on the plank, on which he stillremained seated while the two supernumeraries busied themselves incompleting his toilet for him; one screwing on his helmet, whichappeared ridiculously large, the other loading his breast and back withtwo heavy leaden weights. When fully equipped, the diver carried on hisperson a weight fully equal to that of his own bulky person.

"Now look here, Mister Edgar, an' pay partikler attention, RooneyMachowl. This here toobe, made of indyrubber, d'ee see? (`Yis, sur,'from Rooney) I fix on, as you perceive, to the back of Maxwell's helmet.It communicates with that there pump, and when these two men work thepump, air will be forced into the helmet and into the dress down to hisvery toes. We could bu'st him, if we were so disposed, if it wasn't foran escape-valve, here close beside the air-toobe, at the back of thehelmet, which keeps lettin' off the surplus air. Moreover, there isanother valve, here in front of the breast-plate, which is under thecontrol of the diver, so that he can let air escape by givin' it ahalf-turn when the men at the pumps are givin' him too much, or he cankeep it in when they're givin' him enough."

"An' what does he do," asked Rooney, with an anxious expression, "whinthey give him too little?"

"He pulls on the air-pipe,--as I'll explain to you in good time--theproper signal for `more air.'"

"But what if he forgits, or misremimbers the signal?" asked theinquisitive recruit.

"Why then," replied Baldwin, "he suffocates, and we pull him up dead,an' give him decent burial. Keep yourself easy, my lad, an' you'll knowall about it in good time. I'll soon give 'ee the chance to suffocateor bu'st yourself accordin' to taste."

"Come, cut it short and look alive," said Maxwell gruffly, as he stoodup to permit of a stout rope being fastened to his waist.

"You shut up!" retorted Baldwin.

Having exchanged these little civilities the two divers moved to theside of the barge--Maxwell with a slow ponderous tread.

A short iron ladder dipped from the gunwale of the barge a few feet downinto the sea. The diver stepped upon this,

turning with his faceinwards, descended knee-deep into the water, and then stopped. Baldwinhanded him the blasting-charge. At the same moment one of thesupernumeraries advanced with the front-glass or bull's-eye in his hand,and the men at the pumps gave a turn or two to see that all was workingwell.

"All right?" demanded the supernumerary.

"Right," responded Maxwell, in a voice which issued sepulchrally fromthe iron globe.

There are three round windows fitted with thick plate-glass in thehelmets to which we refer. The front one is made to screw off and on,and the fixing of this is always the last operation in completing adiver's toilet.

"Pump away," said the man, holding the round glass in front of Maxwell'snose, and looking over his shoulder to see that the order was obeyed.The glass was screwed on, and the man finished off by gravely pattingMaxwell in an affectionate manner on the head.

"Why does he pat him so?" asked Edgar, with a laugh at the apparenttenderness of the act.

"It's a tinder farewell, I suppose," murmured Rooney, "in case he nivercomes up again."

"It is to let him know that he may now descend in safety," answeredBaldwin. "The pump there is kep' goin' from a few moments before thefront-glass is screwed on till the diver shows his head above wateragain--which he'll do in quarter of an hour or so, for it don't takelong to lay a charge; but our ordinary spell under water, when work issteady, is about four hours--more or less--with perhaps a breath of tenminutes once or twice at the surface when they're working deep."

"But why a breath at the surface?" asked Edgar. "Isn't the air sentdown fresh enough?"

"Quite fresh enough, Mister Edgar, but the pressure when we go deep--sayten or fifteen fathoms--is severe on a man if long continued, so that heneeds a little relief now and then. Some need more and some lessrelief, accordin' to their strength. Maxwell has only gone down fifteenfeet, so that he wouldn't need to come up at all durin' a spell of work.We're goin' to blast a big rock that has bin' troublesome to us at lowwater. The hole was driven in it last week. We moored a raft over itand kep' men at work with a long iron jumper that reached from the rockto the surface of the sea. It was finished last night, and now he'sgone to fix the charge."

"But I don't understand about the pressure, sur, at all at all," saidMachowl, with a complicated look of puzzlement; "sure whin I putt myhand in wather I don't feel no pressure whatsomediver."

"Of course not," responded Baldwin, "because you don't put it deepenough. You must know that our atmosphere presses on our bodies with aweight of about 20,000 pounds. Well, if you go thirty-two feet deep inthe sea you get the pressure of exactly another atmosphere, which meansthat you've got to stand a pressure all over your body of 40,000 whenyou've got down as deep as thirty-two feet."

"But," objected Rooney, "I don't fed no pressure of the atmosphere on mebody at all."

"That's because you're squeezed by the air inside of you, man, as wellas by the atmosphere outside, which takes off the _feelin'_ of it, an',moreover, you're used to it. If the weight of our atmosphere was tookoff your outside and not took off your inside--your lungs an' thelike,--you'd come to feel it pretty strong, for you'd swell like aballoon an' bu'st a'most, if not altogether."

Baldwin paused a moment and regarded the puzzled countenance of hispupil with an air of pity.

"Contrairywise," he continued, "if the air was all took out of yourinside an' allowed to remain on your outside, you'd go squash togetherlike a collapsed indyrubber ball. Well then, if that be so with oneatmosphere, what must it be with a pressure equal to two, which you havewhen you go down to thirty-two feet deep in the sea? An' if you go downto twenty-five fathoms, or 150 feet, which is often done, what must thepressure be there?"

"Tightish, no doubt," said Rooney.

"True, lad," continued Joe. "Of course, to counteract this we mustforce more air down to you the deeper you go, so that the pressureinside of you may be a little more than the pressure outside, in orderto force the foul air out of the dress through the escape-valve; andwhat between the one an' the other your sensations are peculiar, you maybe sure.--But come, young man, don't be alarmed. We'll not send youdown very deep at first. If some divers go down as deep as twenty-fivefathoms, surely you'll not be frightened to try two and a half."

Whatever Rooney's feelings might have been, the judicious allusion tothe possibility of his being frightened was sufficient to call forth theemphatic assertion that he was ready to go down two thousand fathoms ifthey had ropes long enough and weights heavy enough to sink him!

While the recruit is preparing for his subaqueous experiments, you andI, reader, will go see what Maxwell is about at the bottom of the sea.