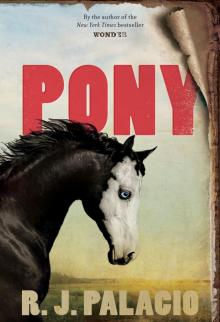

Pony

R. J. Palacio

ALSO BY R. J. PALACIO

Wonder

365 Days of Wonder

Auggie & Me

We’re All Wonders

White Bird

this is a borzoi book published by alfred a. knopf

This is a work of fiction. All incidents and dialogue, and all characters with the exception of some well-known historical and public figures, are products of the author’s imagination and are not to be construed as real. Where real-life historical or public figures appear, the situations, incidents, and dialogues concerning those persons are fictional and are not intended to depict actual events or to change the fictional nature of the work. In all other respects, any resemblance to persons living or dead is entirely coincidental.

Text copyright © 2021 by R. J. Palacio

Cover images (horse, scenery) used under license from Shutterstock.com

Cover design by 1000Jars

Interior image (horse) used under license from Shutterstock.com

Interior image (moon) The Moon, 1857 copyright © by Getty Images

All other interior images courtesy of the author

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Alfred A. Knopf, an imprint of Random House Children’s Books, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York.

Knopf, Borzoi Books, and the colophon are registered trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC.

Visit us on the Web! rhcbooks.com

Educators and librarians, for a variety of teaching tools, visit us at RHTeachersLibrarians.com

Library of Congress Control Number: 2021941721

ISBN 9780553508116 (trade) — ISBN 9780553508123 (lib. bdg.) — ebook ISBN 9780553508130

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Random House Children’s Books supports the First Amendment and celebrates the right to read.

Penguin Random House LLC supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin Random House to publish books for every reader.

ep_prh_5.7.1_c0_r0

Contents

Cover

Also by R. J. Palacio

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Epigraph

Part One

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Part Two

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Part Three

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Part Four

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Part Five

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Part Six

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Part Seven

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Part Eight

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Part Nine

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Part Ten

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Part Eleven

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Author’s Note

Acknowledgments

For my mother

Our natures can’t be spoken…

—Margot Livesey Eva Moves the Furniture

Fare thee well, I must be gone

And leave you for a while.

But wherever I go, I will return,

If I go ten thousand miles.

Ten thousand miles, my own true love,

Ten thousand miles or more.

And the rocks may melt and the seas may burn,

If I no more return.

Oh, come back, my own true love,

And stay a while with me.

For if I had a friend all on this earth,

You’ve been a friend to me.

—Anonymous “Fare Thee Well”

ONE

I have left Ithaca to seek him.

—François Fénelon The Adventures of Telemachus, 1699

From the Boneville Courier, April 27, 1858:

A country boy of ten living near Boneville was, recently, walking to his house in the vicinity of a large oak tree, when a violent storm arose. The boy took refuge beneath the tree scant moments before it was struck by lightning, sending the boy tumbling to the earth, as if lifeless, his clothes smoked to cinders. Fortune smiled upon the child that day, however, for his quick-witted father, having witnessed the event, was able to revive him by means of a fireplace bellows. The child remained unaltered by the experience afterward but for one peculiar souvenir—an image of the tree had become emblazoned upon his back! This “daguerreotype by lightning” is one of several documented in recent years, making it yet another wondrous curiosity of science.

1

IT WAS MY BOUT WITH LIGHTNING that inspired Pa to become immersed in the photographic sciences, which is how this all began.

Pa had always had a natural curiosity about photography, having come from Scotland, where such arts flourish. He dabbled in daguerreotypes for a short while after settling in Ohio, a region naturally full of salt springs (from which comes the agent bromine, an essential component of the developing process). But daguerreotypes were an expensive enterprise that turned very little profit, and Pa did not have the means to pursue it. People haven’t the money for delicate souvenirs, he reasoned. Which is why he became a boot-maker. People always have a need for boots, he said. Pa’s specialty was the calf-high Wellington in grain leather, to which he added a secret compartment in the heel for the storing of tobacco or a pocketknife. This convenience was greatly desired by customers, so we got by pretty well on those boot orders. Pa worked in the shed next to the barn, and once a month traveled to Boneville with a cartful of boots pulled by Mule, our mule.

But after lightning imprinted my back with the image of the oak tree,

Pa once again turned his attention to the science of photography. It was his belief that the image on my skin had come there as a consequence of the same chemical reactions at play in photography. The human body, he told me as I watched him mixing chemicals that smelled of rotten eggs and cider vinegar, is a vessel full of the same mysterious substances, subject to the same physical laws, as everything else in the universe. If an image can be preserved by the action of light upon your body, it can be preserved by the same action upon paper. That is why it was not daguerreotypes that drew his interest anymore, but a new form of photography involving paper soaked in a solution of iron and salt, to which is transferred, by means of sunlight, a positive image from a glass negative.

Pa quickly mastered the new science, and became a highly regarded practitioner of the collodion process, as it was called, an art form hardly seen in these parts. It was a bold field, requiring great experimentation, and resulting in pictures most astounding in their beauty. Pa’s irontypes, as he called them, had none of the exactitude of daguerreotypes, but were imbued with subtle shadings that made them look like charcoal art. He used his own proprietary formula for the sensitizer, which is where the bromine came in, and applied for a patent before opening a studio in Boneville, down the road from the courthouse. In no time at all, his iron-dusted paper portraits became quite the rage around here, for not only were they infinitely cheaper than daguerreotypes, but they could be reproduced over and over again from a single negative. Adding even more to their allure, and for an extra charge, Pa would tint them with a mix of egg wash and colored pigment, which gave them a lifelike semblance most extraordinary to behold. People traveled from all over to have their portraits taken. One fancy lady came all the way from Akron for a sitting. I assisted in Pa’s studio, adjusting the skylight and cleaning the focusing plates. A few times Pa even let me polish the new brass portrait lens, which had been a major investment in the business and required delicacy in its handling. Such had our circumstances turned, Pa’s and mine, that he was contemplating selling his boot-making enterprise altogether, for he said he much preferred the smell of mixing potions to the stink of people’s feet.

It was at this time that our lives were forever changed by the predawn visitation of three riders and a bald-faced pony.

2

MITTENWOOL WAS THE ONE WHO roused me from my deep slumber that night.

“Silas, awake now. There are riders coming this way,” he said.

I would be lying if I said I was jolted up right away, to my feet, by the urgency of his call. But I did no such thing. I simply mumbled something and turned in my bed. He nudged me hard then, which is not a simple feat for him. Ghosts do not easily maneuver in the material world.

“Let me sleep,” I answered grumpily.

It was then that I heard Argos howling like a banshee downstairs, and Pa cock his rifle. I looked out the tiny window next to my bed, but it was a black-as-ink night and I could see nothing.

“There are three of them,” said Mittenwool, squinting over my shoulder through the same window.

“Pa?” I called out, jumping down from the loft. He was ready, boots on, peering through the front window.

“Stay down, Silas,” he cautioned.

“Should I light the lamp?”

“No. Did you see them from your window? How many are there?” he asked.

“I didn’t see them myself, but Mittenwool says there are three of them.”

“Guns drawn,” Mittenwool added.

“They have their guns drawn,” I said. “What do they want, Pa?”

Pa didn’t answer. We could hear the galloping coming toward us now. Pa cracked the front door open, rifle at the ready. He threw on his coat and turned to look at me.

“You don’t come out, Silas. No matter what,” he said, his voice stern. “If there’s trouble, you run over to Havelock’s house. Out the back through the fields. You hear me?”

“You’re not going out there, are you?”

“Get ahold of Argos,” he answered. “Don’t let him out.”

I collared Argos. “You’re not going out there, are you?” I asked again, frightened.

He did not stop to answer me but opened the door and ventured out to the porch, aiming his rifle toward the approaching riders. He was a brave man, my pa.

I pulled Argos close to me and then crept over to the front window and peeked out. I saw the men advance. Three riders, just like Mittenwool had said. Behind one of them trailed a fourth horse, a giant black charger, and next to it, the pony with a bone-white face.

The horsemen slowed down as they approached the house, in deference to Pa’s rifle. The leader of the three, a man in a yellow duster on a spotted horse, put his arms up in the air in a peaceful gesture as he brought his steed to a full stop.

“Ho there,” he said to Pa, not forty feet from the porch. “You can put down your weapon, mister. I come in peace.”

“Put yours down first,” Pa answered, his rifle shouldered.

“Mine?” The man looked theatrically at his own empty hands, and then left and right, making a show of only now noting his companions’ drawn weapons. “Put those down, boys! You’re making a bad impression.” He turned back to Pa. “Sorry about that. They mean no harm. Just force of habit.”

“Who are you?” Pa said.

“Are you Mac Boat?”

Pa shook his head. “Who are you? Come storming here in the middle of the night.”

The yellow-duster man did not seem afraid of Pa’s rifle in the least. I could not see him well in the dark, but I judged him to be smaller than Pa (Pa being one of the tallest men in Boneville). Younger, too. He wore a derby hat like gentlemen do, but he wasn’t one, as far as I could see. He looked a ruffian. Pointy-bearded.

“Now, now, don’t get riled,” he said, his voice light. “My boys and I meant to arrive at sunup, but we made better time than we thought. I’m Rufe Jones, and these here are Seb and Eben Morton. Don’t bother trying to tell them apart, it’s impossible.” It was only then that I noted the two hulking men were exact duplicates of each other, wearing identical melon hats with wide bands down low over their moon-round faces. “We’ve come here with an interesting proposition from our boss, Roscoe Ollerenshaw. You heard of him, I’m sure?”

Pa made no response to that.

“Well, Mr. Ollerenshaw knows of you, Mac Boat,” Rufe Jones continued.

“Who is Mac Boat?” Mittenwool whispered to me.

“I don’t know any Mac Boat,” Pa said from behind his rifle. “I am Martin Bird.”

“Of course,” Rufe Jones answered quickly, nodding. “Martin Bird, the photographer. Mr. Ollerenshaw’s very familiar with your work! That’s why we’re here, you see. He has a business proposition he’d like to discuss with you. We’ve come a long way to talk with you. Might we come inside for a bit? We’ve been riding all night. My bones are chilled.” He raised the collar on his duster to illustrate the point.

“If you want to talk business, you come to my studio in the daylight hours like any civilized man would,” Pa said.

“Now, why would you adopt that tone with me?” Rufe Jones asked, as if perplexed. “The nature of our business requires some privacy, is all. We mean you no harm, not you or your boy, Silas. That’s him hovering by the window behind you, right?”

I swallowed hard, I’m not going to lie, and pulled my head back from the window. Mittenwool, who was behind me, nudged me to crouch down farther.

“You have five seconds to get off my property,” Pa warned, and I could tell from his voice he meant it.

But Rufe Jones must not have heard the threatening tone in Pa’s words, for he laughed. “Now, now, don’t get vexed. I’m just the messenger here!” he replied calmly. “Mr. Ollerenshaw sent us to come get you, and that’s what we’re doing. Like I said

, he means you no harm. In fact, he wants to help you. He wanted me to tell you there’s a lot of money in it for you. A small fortune were his exact words. For very little inconvenience on your part. Just a week’s work and you’ll be a rich man. We even brought you horses to ride! A nice big one for you, and a fetching little one for your boy. Mr. Ollerenshaw is something of a horse collector, so you should consider it an honor that he’s letting you ride his fine steeds.”

“I’m not interested. You now have three seconds to leave,” answered Pa. “Two…”

“All right, all right!” said Rufe Jones, waving his hands in the air. “We’ll leave. Don’t you worry! Come on, fellas.”

He pulled on his horse’s reins and circled around, as did the brothers, wheeling the two riderless horses behind them. They started slow-walking into the night away from the house. But after a few steps, Rufe Jones stopped. He held his arms out to his sides, crucifixion-like, to show he was still unarmed. Then he looked over his shoulder at Pa.

“But we’ll only come back tomorrow,” he said, “with a lot more men. Mr. Ollerenshaw is not one to give up easily, truth be told. I came in peace tonight, but I can’t promise it’ll be the same tomorrow. Mr. Ollerenshaw, well, he wants what he wants.”