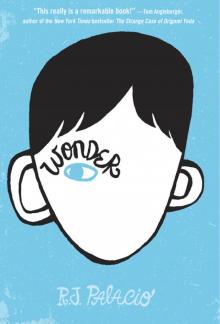

Wonder

R. J. Palacio

THIS IS A BORZOI BOOK PUBLISHED BY ALFRED A. KNOPF

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

Text copyright © 2012 by R. J. Palacio

Jacket art copyright © 2012 by Tad Carpenter

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Alfred A. Knopf,

an imprint of Random House Children’s Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York.

Knopf, Borzoi Books, and the colophon are registered trademarks of Random House, Inc.

Permissions can be found on this page.

Visit us on the Web! randomhouse.com/kids

Educators and librarians, for a variety of teaching tools, visit us at randomhouse.com/teachers

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Palacio, R. J.

Wonder / by R.J. Palacio.

p. cm.

Summary: Ten-year-old Auggie Pullman, who was born with extreme facial abnormalities and was not expected to survive, goes from being home-schooled to entering fifth grade at a private middle school in Manhattan, which entails enduring the taunting and fear of his classmates as he struggles to be seen as just another student.

eISBN: 978-0-375-89988-1

[1. Abnormalities, Human—Fiction. 2. Self-importance—Fiction. 3. Middle schools—Fiction. 4. Schools—Fiction.] I. Title.

PZ7.P17526Wo 2012

[Fic]—dc23

2011027133

February 2012

Random House Children’s Books supports the First Amendment and celebrates the right to read.

v3.1

For Russell, Caleb, and Joseph

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Epigraph

Part One: August

Ordinary

Why I Didn’t Go to School

How I Came to Life

Christopher’s House

Driving

Paging Mr. Tushman

Nice Mrs. Garcia

Jack Will, Julian, and Charlotte

The Grand Tour

The Performance Space

The Deal

Home

First-Day Jitters

Locks

Around the Room

Lamb to the Slaughter

Choose Kind

Lunch

The Summer Table

One to Ten

Padawan

Wake Me Up when September Ends

Jack Will

Mr. Browne’s October Precept

Apples

Halloween

School Pictures

The Cheese Touch

Costumes

The Bleeding Scream

Names

Part Two: Via

A Tour of the Galaxy

Before August

Seeing August

August Through the Peephole

High School

Major Tom

After School

The Padawan Bites the Dust

An Apparition at the Door

Breakfast

Genetics 101

The Punnett Square

Out with the Old

October 31

Trick or Treat

Time to Think

Part Three: Summer

Weird Kids

The Plague

The Halloween Party

November

Warning: This Kid Is Rated R

The Egyptian Tomb

Part Four: Jack

The Call

Carvel

Why I Changed My Mind

Four Things

Ex-Friends

Snow

Fortune Favors the Bold

Private School

In Science

Partners

Detention

Season’s Greetings

Letters, Emails, Facebook, Texts

Back from Winter Break

The War

Switching Tables

Why I Didn’t Sit with August the First Day of School

Sides

August’s House

The Boyfriend

Part Five: Justin

Olivia’s Brother

Valentine’s Day

Our Town

Ladybug

The Bus Stop

Rehearsal

Bird

The Universe

Part Six: August

North Pole

The Auggie Doll

Lobot

Hearing Brightly

Via’s Secret

My Cave

Goodbye

Daisy’s Toys

Heaven

Understudy

The Ending

Part Seven: Miranda

Camp Lies

School

What I Miss Most

Extraordinary, but No One There to See

The Performance

After the Show

Part Eight: August

The Fifth-Grade Nature Retreat

Known For

Packing

Daybreak

Day One

The Fairgrounds

Be Kind to Nature

The Woods Are Alive

Alien

Voices in the Dark

The Emperor’s Guard

Sleep

Aftermath

Home

Bear

The Shift

Ducks

The Last Precept

The Drop-Off

Take Your Seats, Everyone

A Simple Thing

Awards

Floating

Pictures

The Walk Home

Appendix

Acknowledgments

Permissions

Doctors have come from distant cities

just to see me

stand over my bed

disbelieving what they’re seeing

They say I must be one of the wonders

of god’s own creation

and as far as they can see they can offer

no explanation

—NATALIE MERCHANT, “Wonder”

Fate smiled and destiny

laughed as she came to my cradle …

—Natalie Merchant, “Wonder”

Ordinary

I know I’m not an ordinary ten-year-old kid. I mean, sure, I do ordinary things. I eat ice cream. I ride my bike. I play ball. I have an XBox. Stuff like that makes me ordinary. I guess. And I feel ordinary. Inside. But I know ordinary kids don’t make other ordinary kids run away screaming in playgrounds. I know ordinary kids don’t get stared at wherever they go.

If I found a magic lamp and I could have one wish, I would wish that I had a normal face that no one ever noticed at all. I would wish that I could walk down the street without people seeing me and then doing that look-away thing. Here’s what I think: the only reason I’m not ordinary is that no one else sees me that way.

But I’m kind of used to how I look by now. I know how to pretend I don’t see the faces people make. We’ve all gotten pretty good at that sort of thing: me, Mom and Dad, Via. Actually, I take that back: Via’s not so good at it. She can get really annoyed when people do something rude. Like, for instance, one time in the playground some older kids made some noises. I don’t even know what the noises were exactly because I didn’t hear them myself, but Via heard and she just started yelling at the kids. That’s the way she is. I’m not that way.

Via doesn’t see me as ordinary. She says she does, but if I were ordinary, she wouldn’t feel lik

e she needs to protect me as much. And Mom and Dad don’t see me as ordinary, either. They see me as extraordinary. I think the only person in the world who realizes how ordinary I am is me.

My name is August, by the way. I won’t describe what I look like. Whatever you’re thinking, it’s probably worse.

Why I Didn’t Go to School

Next week I start fifth grade. Since I’ve never been to a real school before, I am pretty much totally and completely petrified. People think I haven’t gone to school because of the way I look, but it’s not that. It’s because of all the surgeries I’ve had. Twenty-seven since I was born. The bigger ones happened before I was even four years old, so I don’t remember those. But I’ve had two or three surgeries every year since then (some big, some small), and because I’m little for my age, and I have some other medical mysteries that doctors never really figured out, I used to get sick a lot. That’s why my parents decided it was better if I didn’t go to school. I’m much stronger now, though. The last surgery I had was eight months ago, and I probably won’t have to have any more for another couple of years.

Mom homeschools me. She used to be a children’s-book illustrator. She draws really great fairies and mermaids. Her boy stuff isn’t so hot, though. She once tried to draw me a Darth Vader, but it ended up looking like some weird mushroom-shaped robot. I haven’t seen her draw anything in a long time. I think she’s too busy taking care of me and Via.

I can’t say I always wanted to go to school because that wouldn’t be exactly true. What I wanted was to go to school, but only if I could be like every other kid going to school. Have lots of friends and hang out after school and stuff like that.

I have a few really good friends now. Christopher is my best friend, followed by Zachary and Alex. We’ve known each other since we were babies. And since they’ve always known me the way I am, they’re used to me. When we were little, we used to have playdates all the time, but then Christopher moved to Bridgeport in Connecticut. That’s more than an hour away from where I live in North River Heights, which is at the top tip of Manhattan. And Zachary and Alex started going to school. It’s funny: even though Christopher’s the one who moved far away, I still see him more than I see Zachary and Alex. They have all these new friends now. If we bump into each other on the street, they’re still nice to me, though. They always say hello.

I have other friends, too, but not as good as Christopher and Zack and Alex were. For instance, Zack and Alex always invited me to their birthday parties when we were little, but Joel and Eamonn and Gabe never did. Emma invited me once, but I haven’t seen her in a long time. And, of course, I always go to Christopher’s birthday. Maybe I’m making too big a deal about birthday parties.

How I Came to Life

I like when Mom tells this story because it makes me laugh so much. It’s not funny in the way a joke is funny, but when Mom tells it, Via and I just start cracking up.

So when I was in my mom’s stomach, no one had any idea I would come out looking the way I look. Mom had had Via four years before, and that had been such a “walk in the park” (Mom’s expression) that there was no reason to run any special tests. About two months before I was born, the doctors realized there was something wrong with my face, but they didn’t think it was going to be bad. They told Mom and Dad I had a cleft palate and some other stuff going on. They called it “small anomalies.”

There were two nurses in the delivery room the night I was born. One was very nice and sweet. The other one, Mom said, did not seem at all nice or sweet. She had very big arms and (here comes the funny part), she kept farting. Like, she’d bring Mom some ice chips, and then fart. She’d check Mom’s blood pressure, and fart. Mom says it was unbelievable because the nurse never even said excuse me! Meanwhile, Mom’s regular doctor wasn’t on duty that night, so Mom got stuck with this cranky kid doctor she and Dad nicknamed Doogie after some old TV show or something (they didn’t actually call him that to his face). But Mom says that even though everyone in the room was kind of grumpy, Dad kept making her laugh all night long.

When I came out of Mom’s stomach, she said the whole room got very quiet. Mom didn’t even get a chance to look at me because the nice nurse immediately rushed me out of the room. Dad was in such a hurry to follow her that he dropped the video camera, which broke into a million pieces. And then Mom got very upset and tried to get out of bed to see where they were going, but the farting nurse put her very big arms on Mom to keep her down in the bed. They were practically fighting, because Mom was hysterical and the farting nurse was yelling at her to stay calm, and then they both started screaming for the doctor. But guess what? He had fainted! Right on the floor! So when the farting nurse saw that he had fainted, she started pushing him with her foot to get him to wake up, yelling at him the whole time: “What kind of doctor are you? What kind of doctor are you? Get up! Get up!” And then all of a sudden she let out the biggest, loudest, smelliest fart in the history of farts. Mom thinks it was actually the fart that finally woke the doctor up. Anyway, when Mom tells this story, she acts out all the parts—including the farting noises—and it is so, so, so, so funny!

Mom says the farting nurse turned out to be a very nice woman. She stayed with Mom the whole time. Didn’t leave her side even after Dad came back and the doctors told them how sick I was. Mom remembers exactly what the nurse whispered in her ear when the doctor told her I probably wouldn’t live through the night: “Everyone born of God overcometh the world.” And the next day, after I had lived through the night, it was that nurse who held Mom’s hand when they brought her to meet me for the first time.

Mom says by then they had told her all about me. She had been preparing herself for the seeing of me. But she says that when she looked down into my tiny mushed-up face for the first time, all she could see was how pretty my eyes were.

Mom is beautiful, by the way. And Dad is handsome. Via is pretty. In case you were wondering.

Christopher’s House

I was really bummed when Christopher moved away three years ago. We were both around seven then. We used to spend hours playing with our Star Wars action figures and dueling with our lightsabers. I miss that.

Last spring we drove over to Christopher’s house in Bridgeport. Me and Christopher were looking for snacks in the kitchen, and I heard Mom talking to Lisa, Christopher’s mom, about my going to school in the fall. I had never, ever heard her mention school before.

“What are you talking about?” I said.

Mom looked surprised, like she hadn’t meant for me to hear that.

“You should tell him what you’ve been thinking, Isabel,” Dad said. He was on the other side of the living room talking to Christopher’s dad.

“We should talk about this later,” said Mom.

“No, I want to know what you were talking about,” I answered.

“Don’t you think you’re ready for school, Auggie?” Mom said.

“No,” I said.

“I don’t, either,” said Dad.

“Then that’s it, case closed,” I said, shrugging, and I sat in her lap like I was a baby.

“I just think you need to learn more than I can teach you,” Mom said. “I mean, come on, Auggie, you know how bad I am at fractions!”

“What school?” I said. I already felt like crying.

“Beecher Prep. Right by us.”

“Wow, that’s a great school, Auggie,” said Lisa, patting my knee.

“Why not Via’s school?” I said.

“That’s too big,” Mom answered. “I don’t think that would be a good fit for you.”

“I don’t want to,” I said. I admit: I made my voice sound a little babyish.

“You don’t have to do anything you don’t want to do,” Dad said, coming over and lifting me out of Mom’s lap. He carried me over to sit on his lap on the other side of the sofa. “We won’t make you do anything you don’t want to do.”

“But it would be good for him, Nate,” Mom said.

“Not if he doesn’t want to,” answered Dad, looking at me. “Not if he’s not ready.”

I saw Mom look at Lisa, who reached over and squeezed her hand.

“You guys will figure it out,” she said to Mom. “You always have.”

“Let’s just talk about it later,” said Mom. I could tell she and Dad were going to get in a fight about it. I wanted Dad to win the fight. Though a part of me knew Mom was right. And the truth is, she really was terrible at fractions.

Driving

It was a long drive home. I fell asleep in the backseat like I always do, my head on Via’s lap like she was my pillow, a towel wrapped around the seat belt so I wouldn’t drool all over her. Via fell asleep, too, and Mom and Dad talked quietly about grown-up things I didn’t care about.

I don’t know how long I was sleeping, but when I woke up, there was a full moon outside the car window. It was a purple night, and we were driving on a highway full of cars. And then I heard Mom and Dad talking about me.

“We can’t keep protecting him,” Mom whispered to Dad, who was driving. “We can’t just pretend he’s going to wake up tomorrow and this isn’t going to be his reality, because it is, Nate, and we have to help him learn to deal with it. We can’t just keep avoiding situations that …”

“So sending him off to middle school like a lamb to the slaughter …,” Dad answered angrily, but he didn’t even finish his sentence because he saw me in the mirror looking up.

“What’s a lamb to the slaughter?” I asked sleepily.

“Go back to sleep, Auggie,” Dad said softly.

“Everyone will stare at me at school,” I said, suddenly crying.

“Honey,” Mom said. She turned around in the front seat and put her hand on my hand. “You know if you don’t want to do this, you don’t have to. But we spoke to the principal there and told him about you and he really wants to meet you.”

“What did you tell him about me?”

“How funny you are, and how kind and smart. When I told him you read Dragon Rider when you were six, he was like, ‘Wow, I have to meet this kid.’ ”

“Did you tell him anything else?” I said.

Mom smiled at me. Her smile kind of hugged me.

“I told him about all your surgeries, and how brave you are,” she said.