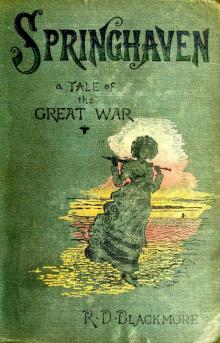

Springhaven: A Tale of the Great War

R. D. Blackmore

Produced by Don Lainson

SPRINGHAVEN:

A Tale of the Great War

By R. D. Blackmore

1887

CHAPTER I

WHEN THE SHIP COMES HOME

In the days when England trusted mainly to the vigor and valor of oneman, against a world of enemies, no part of her coast was in greaterperil than the fair vale of Springhaven. But lying to the west of thenarrow seas, and the shouts both of menace and vigilance, the quietlittle village in the tranquil valley forbore to be uneasy.

For the nature of the place and race, since time has outlived memory,continually has been, and must be, to let the world pass easily. Littleto talk of, and nothing to do, is the healthy condition of mankind justthere. To all who love repose and shelter, freedom from the cares ofmoney and the cark of fashion, and (in lieu of these) refreshing air,bright water, and green country, there is scarcely any valley left tocompare with that of Springhaven. This valley does not interrupt theland, but comes in as a pleasant relief to it. No glaring chalk, nogrim sandstone, no rugged flint, outface it; but deep rich meadows, andfoliage thick, and cool arcades of ancient trees, defy the noise thatmen make. And above the trees, in shelving distance, rise the crests ofupland, a soft gray lias, where orchards thrive, and greensward strokesdown the rigor of the rocks, and quick rills lace the bosom of the slopewith tags of twisted silver.

In the murmur of the valley twenty little waters meet, and discoursingtheir way to the sea, give name to the bay that receives them and theanchorage they make. And here no muddy harbor reeks, no foul mouthof rat-haunted drains, no slimy and scraggy wall runs out, to mar themeeting of sweet and salt. With one or two mooring posts to watch it,and a course of stepping-stones, the brook slides into the peaceful bay,and is lost in larger waters. Even so, however, it is kindly still, forit forms a tranquil haven.

Because, where the ruffle of the land stream merges into the heavierdisquietude of sea, slopes of shell sand and white gravel give welcomepillow to the weary keel. No southerly tempest smites the bark, no longgroundswell upheaves her; for a bold point, known as the "Haven-head,"baffles the storm in the offing, while the bulky rollers of a strongspring-tide, that need no wind to urge them, are broken by the shiftingof the shore into a tier of white-frilled steps. So the deep-waistedsmacks that fish for many generations, and even the famous "Londontrader" (a schooner of five-and-forty tons), have rest from theirlabors, whenever they wish or whenever they can afford it, in thearms of the land, and the mouth of the water, and under the eyes ofSpringhaven.

At the corner of the wall, where the brook comes down, and pebble turnsinto shingle, there has always been a good white gate, respected (as awhite gate always is) from its strong declaration of purpose. Outsideof it, things may belong to the Crown, the Admiralty, Manor, or TrinityBrethren, or perhaps the sea itself--according to the latest ebb orflow of the fickle tide of Law Courts--but inside that gate everythingbelongs to the fine old family of Darling.

Concerning the origin of these Darlings divers tales are told, accordingto the good-will or otherwise of the diver. The Darlings themselvescontend and prove that stock and name are Saxon, and the true form ofthe name is "Deerlung," as witness the family bearings. But the foes ofthe race, and especially the Carnes, of ancient Sussex lineage, declarethat the name describes itself. Forsooth, these Darlings are nothingmore, to their contemptuous certainty, than the offset of somecourt favorite, too low to have won nobility, in the reign of somelight-affectioned king.

If ever there was any truth in that, it has been worn out long ago byfriction of its own antiquity. Admiral Darling owns that gate, andall the land inside it, as far as a Preventive man can see with hisspy-glass upon the top bar of it. And this includes nearly all thevillage of Springhaven, and the Hall, and the valley, and the hills thatmake it. And how much more does all this redound to the credit of thefamily when the gazer reflects that this is nothing but their youngertenement! For this is only Springhaven Hall, while Darling Holt, theheadquarters of the race, stands far inland, and belongs to Sir Francis,the Admiral's elder brother.

When the tides were at their spring, and the year 1802 of our era inthe same condition, Horatia Dorothy Darling, younger daughter of theaforesaid Admiral, choosing a very quiet path among thick shrubs andunder-wood, came all alone to a wooden building, which her father calledhis Round-house. In the war, which had been patched over now, but wouldvery soon break out again, that veteran officer held command of thecoast defense (westward of Nelson's charge) from Beachy Head to SelseyBill. No real danger had existed then, and no solid intent of invasion,but many sharp outlooks had been set up, and among them was this atSpringhaven.

Here was established under thatch, and with sliding lights before it,the Admiral's favorite Munich glass, mounted by an old ship's carpenter(who had followed the fortunes of his captain) on a stand which wouldhave puzzled anybody but the maker, with the added security of a lanyardfrom the roof. The gear, though rough, was very strong and solid,and afforded more range and firmer rest to the seven-feet tube andadjustments than a costly mounting by a London optician would have beenlikely to supply. It was a pleasure to look through such a glass, soclear, and full of light, and firm; and one who could have borne tobe looked at through it, or examined even by a microscope, came now toenjoy that pleasure.

Miss Dolly Darling could not be happy--though her chief point was tobe so--without a little bit of excitement, though it were of her ownconstruction. Her imagination, being bright and tender and lively,rather than powerful, was compelled to make its own material, out ofvery little stuff sometimes. She was always longing for something sweetand thrilling and romantic, and what chance of finding it in thisdull place, even with the longest telescope? For the war, with all itsstirring rumors and perpetual motion on shore and sea, and access ofgallant visitors, was gone for the moment, and dull peace was signed.

This evening, as yet, there seemed little chance of anything to enlivenher. The village, in the valley and up the stream, was hidden by turnsof the land and trees; her father's house beneath the hill crest was outof sight and hearing; not even a child was on the beach; and the onlymovement was of wavelets leisurely advancing toward the sea-wall fringedwith tamarisk. The only thing she could hope to see was the happy returnof the fishing-smacks, and perhaps the "London trader," inasmuch as thefishermen (now released from fencible duty and from French alarm) didtheir best to return on Saturday night to their moorings, their homes,the disposal of fish, and then the deep slumber of Sunday. If the breezeshould enable them to round the Head, and the tide avail for landing,the lane to the village, the beach, and even the sea itself would swarmwith life and bustle and flurry and incident. But Dolly's desire was forscenes more warlike and actors more august than these.

Beauty, however, has an eye for beauty beyond its own looking-glass.Deeply as Dolly began to feel the joy of her own loveliness, she hadmanaged to learn, and to feel as well, that so far as the strength andvigor of beauty may compare with its grace and refinement, she hadher own match at Springhaven. Quite a hardworking youth, of no socialposition and no needless education, had such a fine countenance and suchbright eyes that she neither could bear to look at him nor forbear tothink of him. And she knew that if the fleet came home she would see himon board of the Rosalie.

Flinging on a shelf the small white hat which had scarcely covered herdark brown curls, she lifted and shored with a wooden prop the southerncasement of leaded glass. This being up, free range was given to theswinging telescope along the beach to the right and left, and over theopen sea for miles, and into the measureless haze of air. She couldmanage this glass to the best advantage, through her father's teaching,and c

ould take out the slide and clean the lenses, and even part theobject-glass, and refix it as well as possible. She belonged to theorder of the clever virgins, but scarcely to that of the wise ones.