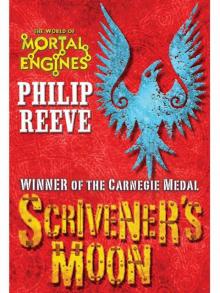

Scrivener's Moon

Philip Reeve

Philip Reeve has WON the CILIP Carnegie Medal,

the Blue Peter Book of the Year, the Nestlé Book Prize –

Gold Award and the Guardian Children’s Fiction Prize

He has been SHORTLISTED for the Whitbread

Children’s Book of the Year and the WHSmith

People’s Choice Awards

Praise for Philip Reeve’s books:

“Philip Reeve’s epic Mortal Engines series has sent the

imagination of many a child completely wild since it first began”

Lovereading4kids.co.uk

“A series worthy of sitting alongside Philip Pullman’s Dark

Materials in the annals of teen fantasy”

Waterstone’s Books Quarterly

“Big, brave, brilliant”

Guardian

“A staggering feat of engineering, a brilliant construction that

offers new wonders at every turn . . . Reeve’s prose is sweeping

and cinematic, his ideas bold and effortless”

Publishers Weekly

“My favourite contemporary children’s author. . .

His books are full of adventure, humour and invention

and are superbly well-written”

Charlie Higson

“The idea behind Mortal Engines has other authors crying ‘I

wish I’d thought of that!’”

Geraldine McCaughrean

“Witty and thrilling, serious and sensitive, Mortal Engines

is one of the most daring and imaginative science fiction

adventures ever written for young readers”

Books for Keeps

“His imagination is electrifying”

Frank Cottrell Boyce

“A ground-breaking futurama”

TES

“Philip Reeve’s intricate imagination makes

J. K. Rowling feel like Enid Blyton”

Independent

“I stayed up till three in the morning to finish it.

Philip Reeve is a genius”

Sonia Benster writing in The Bookseller

“Reeve is a terrific writer”

The Times

“Philip Reeve is a hugely talented and versatile author . . .

the emotional journeys of his characters are enthralling,

never sentimental and always believable”

Daily Telegraph

“There’s a fabulous streak of frivolity running through

everything that Reeve writes. . . Like many of the

great writers who can be read happily by both

adults and children, Reeve uses the frivolity

to hide his own seriousness”

Guardian

“Reeve writes with confidence and power. He is not only a

master of visceral excitement, but at every turn, surprises,

entertains and makes his readers think”

Books for Keeps

“Intelligent, funny and wise”

Literary Review

“Reeve is a master of young adult fiction”

Scotsman

PHILIP REEVE was born in Brighton in 1966. He worked in a bookshop for many years before becoming an illustrator and then an author. His debut novel MORTAL ENGINES, the first in the award-winning epic series, was an instant bestseller and won the Smarties Gold Award. The MORTAL ENGINES quartet and three subsequent prequels cemented his place as one of Britain’s best-loved authors. In 2008 he won the CILIP Carnegie Medal with HERE LIES ARTHUR. He lives with his wife and son on Dartmoor.

www.philip-reeve.com

www.philipreeve.blogspot.com

www.mortalengines.co.uk

By Philip Reeve

Mortal Engines

Predator’s Gold

Infernal Devices

A Darkling Plain

Fever Crumb

A Web of Air

Scrivener’s Moon

No Such Thing As Dragons

Here Lies Arthur

In the BUSTER BAYLISS series:

Night of the Living Veg

The Big Freeze

Day of the Hamster

Custardfinger

Larklight

Starcross

Mothstorm

To Sarah

CONTENTS

Prologue

PART ONE

1 The Homecoming of Fever Crumb

2 Engineerium

3 The Future Sights of London

4 Ancestral Voices

5 Victory Ball

6 The Carnival of Knives

7 News From the North

8 Plans

9 Pies, Spies and Little White Lies

10 Northward Ho!

11 The Revolutionists

12 Across the Dry Sea

13 The Raven’s Nest

14 A Sword at Sunset

PART TWO

15 Nomads’ Land

16 A Rational Man

17 Running True

18 Fever in the Comet’s Tail

19 Charley’s Game

20 Prisoner of the Morvish

21 The Long Shore and the Lonely Hills

22 The Dark Beneath the Fells

23 The Place of the Dead

24 In The Upper Room

25 Besieged

PART THREE

26 Packing Up

27 Phosphorous Fingers

28 Moving On

29 Toasted Sandwich

30 At Three Dry Ships

31 Battle’s End

32 Hungry City

33 The Scrivener’s Moon

Epilogue

PROLOGUE

e forded the river as the daylight died and blundered into thick undergrowth between the birches on the far bank. Sobbing with fright and pain he raised his hand to his chest and felt the hard point of the arrow sticking out through his coat. He dared not look down for fear that the sight of it would make him faint, so he shut his eyes and took the bloodied wooden shaft in both hands, and snapped the head off. Pain knocked him to his knees. Groping behind him he found the feathered end of the arrow where it stuck out above his shoulder blade, braced himself, and wrenched it out. He ripped his handkerchief in half and crammed the pieces into the wounds.

He was a stranger in that country; an explorer; a scientist; a soldier of fortune. His name was Auric Godshawk. In years to come, when age had slowed him, he would be king of London, but on this night he was still in his prime; a strong Scriven male in his sixtieth year, the age hardly showing. That must be how he had survived the ambush, he thought. That must be how he had managed to escape into these woods. Black trees, grey sky, the first stars showing. Cold now the light was gone. He wished he’d brought a hat with him, or gloves. He supposed he had left them behind in the inn or camp or wherever it was that he had been when the ambush happened. His memory seemed to be missing vital chunks. He felt as weak as London wine, and when he looked at his hands they did not seem to belong to him at all; frail, girlish things they seemed, turning blue where they were not crusted with his own blood.

Black trees and a starry sky and his feet crunching through the leaf-litter with sounds like someone munching on an apple. Great Scrivener, what would he not give for an apple?

Then he was lying on his side on the ground and he knew that if he did not rise and make himself go on he would lie there for ever, but he could not rise. He thought of London and his young daughter and wondered if she would ever know what had become of him and he said her name to the night, “Wavey, Wavey,” until it made him start to cry.

And it was daylight, and the stink of mammoth was all about him as he opened his eyes. The animals stood around him like shaggy russet hills. Men moved between their tree-trunk legs. They were talking

about him in words that he could not catch. He wondered if they were planning to save him or finish him, and he said, “Help me! I can pay you. . .”

One of the men drew a knife, but another stopped him and came and crouched at Godshawk’s side. Not a man, he saw now, but a girl, with her long hair escaping in mammoth-coloured curls and tendrils from under her mammoth-fur hat. Weak as he was, Godshawk brightened. He had always had an eye for pretty girls.

“I am Auric Godshawk,” he told her. “I am an important man among my people. Help me. . .”

He was lying among furs in a nomad tent, and nothing moved except the shadows on the low, curving roof. He was burning hot and he tried to push the furs off but the girl was there and she pulled them back over him and touched his forehead with her hand and held it there and it was so cool and she whispered things to him and the light of a woodstove was on her young face and in her red hair. He had seen her before. He remembered her sitting on a mammoth’s back somewhere, watching as he went by.

He tried to speak to her, but she had gone, and now an ugly old man was leaning over him, chanting, singing, humming to himself as he made passes over Godshawk’s face and body with a strange talisman of bones and birch-bark and scraps of age-old circuitry, jingling with little bells. He propped Godshawk on his side and scooped bitter-smelling slime out of an Ancient medicine bottle and smeared it into the wounds in his chest and his back and bound poultices of moss over them. Your Ex-rays have come back from the Lab, he chanted, and held up a sheet of mammoth-skin parchment so fine that the light of the fire shone through it, and Godshawk could see a childish skeleton drawn there, with red-topped pins stuck in to mark his wounds.

When he woke again the man was gone; the girl was back. He lay watching her. A tall girl, big-shouldered and broad across the hips, not a bit like the willow-slender, speckled Scriven women he liked, but her long autumn-coloured hair was lovely in the firelight and her eyes were very large and dark and she made him remember faintly a few of the pleasures of being alive. He called and she came to him and when she leaned over the bed with the loose strands of her hair falling down across his face he said, “Kiss me, mammoth-girl. You’d not deny a last kiss to a dying man?”

Her smile was sweet and quirky. She stooped and touched her warm mouth quickly to his cheek. “You are not a dying man,” she said.

And he dozed in the warm gloom and dreamed of his daughter Wavey, but for some reason he saw her not as the little girl he’d left behind in London but as a woman nearly as old as him, and woke up weeping, and the girl was there with him again and held his hand.

“I dreamed of my daughter. . .” he tried to tell her. He could not explain. Everything was so strange. It was all sliding. His memories were as slippery as slabs of broken ice on a pond. Something was terribly wrong, and he had forgotten what it was. “My little girl. . .”

“Hush,” she said. “You’re feverish.”

For some reason that made him laugh. “Yes! I am feverish. . . I am Feverish. . .”

And it was night and he was alone and he needed to pee, so he clambered out from under the fur covers and the night air was cold on his bare skin and the embers in the woodstove glowed, and as he reached under the bed for the pot he saw a movement from the corner of his eye and looked up, and there was a girl in the shadows watching him.

She was not his mammoth-girl. In his confusion he thought for a moment that she was Wavey, and he started up, and she rose too, but as they walked towards each other he saw that she was a stranger; a Scriven-looking girl, watching him with wide-set, mismatched eyes, one grey, the other brown. Poor mite, he thought, for she was a Blank; the Scrivener had put no markings on her flesh at all. There was an angry star-shaped scar above her breast and as she reached up to touch it he reached up too, in sympathy and understanding, and felt the same scar on his own flesh. Then lost memories started rushing past him like snow and he stretched out his fingers to the girl’s face and touched only the cold surface of a looking glass.

His own numb fear looked back at him out of her widening eyes.

“No!” he shouted. They both shouted it; him and the girl in the mirror, but the only voice he heard was hers. “I am Auric Godshawk! I am Godshawk!”

But he wasn’t. Godshawk had died a long time ago. What remained of him was just a ghost inhabiting the mind of this thin girl, his granddaughter. Her name, he suddenly recalled, was Fever Crumb.

And once he knew that, he could not stay. These thin young hands were not his hands; these eyes were not his eyes; this world was not his world any more. With a terrible sadness he let himself be folded down, like an immense and wonderful map being crumpled into an impossibly small ball, and packed away into the tiny machine that he had once planted, like a silver seed, among the roots of Fever’s brain.

With his last thought, as he left her, he wondered what had brought her here, alone into the north-country with an arrow through her.

PART ONE

1

THE HOMECOMING OF FEVER CRUMB

10 Months Earlier

ever came home to London in a summer storm, her land-barge bowling up the Great South Road beneath a sky full of rainbows.

The city of her birth had changed in the two years that she had been away. Even the lands around it looked different. The woods which once crowded close on either side of the road had been felled, leaving nothing but grey stumps. New settlements had sprung up on the hillsides; loggers’ camps and waystations for the ceaseless convoys of hoys and big-wheeled land-barges which carried timber, steel and pig iron north to London. So she was prepared to find the city altered, but her first sight of it, as her barge grumbled across the Brick Marsh causeways, was still a shock. She stood at the front of the open upper deck, gripping the handrail and squinting into the stormy sunlight and the sharp north wind. She could hardly believe her watering eyes.

The London she had known was gone. On Ludgate Hill most of the old familiar buildings still stood, but they looked odd and isolated, like the last trees of a slaughtered forest. Around the hill’s foot, where slums and rookeries once raised their gambrel roofs, there now stretched empty lots, and tumbled mounds of house-bricks, and rows and rows and rows of pale tents. All that remained of the vanished districts were their temples, like stony islands in a canvas sea, dwarfed by the immense new mills and factories whose chimneys filled the sky above the city with a stormcloud greater and darker than those which were gusting off Hamster’s Heath. And even the factories seemed like toys compared with the new London, which squatted motionless and vast amid their smoke. Its immense chassis, broader than the biggest fleet of barges Fever had ever seen, rested on bank after bank of caterpillar tracks. Two decks or tiers of steel and timber were rising on its back, crammed with housing, bristling with cranes, stitched to the sky with scaffolding, the bright, white points of welders’ torches shining amid the towering girderwork like daytime stars.

“The Lord Mayor’s demolition gangs have spared the temples,” said Fever’s father, Dr Crumb. He stood beside her, holding an umbrella over them both and shouting to make himself heard above the hammering of the barge-engines and the hiss of the wind, which was starting to throw big, chilly raindrops in their faces. “He was afraid of stirring up religious trouble. But they will have to be torn down soon; there is wood and metal and salvage plastic in those buildings which the new city needs. . .”

Fever nodded, watching a last ray of sunlight strike the glittery thunderbolt which crowned the temple of the Thin White Duke. As an Engineer she had no time for London’s silly gods and their temples, but she still felt sad that those great buildings, which had formed the skyline of her childhood, would soon be gone.

A gust blew Dr Crumb’s umbrella inside out and he struggled with it for a moment, then turned away from the rail. “Come, Fever; the weather worsens; let us go inside. . .”

Reluctantly she followed him through the hatch and down the tight twist of wooden stairs. The barge was swaying and jolting a

s its huge wheels bumped down off the causeway’s end on to London cobbles. Fever braced herself against its sudden movements without even noticing. She was used to land-barges. For two years she’d travelled as technician aboard one of them, a mobile theatre called Persimmon’s Electric Lyceum. Right across Europa, all the way to the island city of Mayda . . . but she did not like thinking about Mayda.

Fever’s mother, Wavey Godshawk, London’s Chief Engineer, was waiting for them in the barge’s comfortable cabin. Wavey was a Scriven; the last of that curious, mutant race, and the Scriven liked to stay inside when it was raining, like cats. “Fever,” she purred, when her damp daughter came in, and she brushed Fever’s face with her fingers. Fever hated being touched, but Wavey could not help herself; she loved touching the people she loved; stroking them, caressing them, patting them like pets. She wrapped her silky arms around Dr Crumb from behind and rested her long chin on the top of his head, and Fever stood beside them, and they all three stared out through the wet portholes, watching the water droplets wriggle this way and that like blind glass beetles, watching the new city shift and twist behind the rain.

The barge pulled past Ox-fart Circus, where Godshawk’s Head had once stood: the giant sculpture of Fever’s Scriven grandfather, whose hollow interior had been home to Dr Crumb and London’s other Engineers; the calm, safe home of Fever’s childhood. Now there were only tents, and ranks of those crude, wheeled shelters which the northern nomads called campavans. But even with its buildings gone, London looked more orderly than it had when Fever saw it last. There was fresh lime scattered in the gutters, and wagons were ferrying waste and sewage to pits on the city’s edge. Policemen wearing leather caps with big copper badges strolled in pairs between the tents, or stood directing traffic at the intersections.