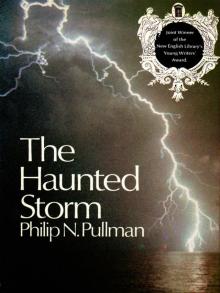

The Haunted Storm

Philip Pullman

To Judy

Chapter 1

At five o’clock in the afternoon of a day in late September, Matthew Cortez went out of his hotel and crossed the road on to the seafront. He hesitated for a moment, and then turned left, and walked swiftly along the front as the first spots of rain began to fall.

He pulled his overcoat tightly around him and turned the collar up, and then thrust his hands deeply into the pockets. The sole of his right shoe was coming away from the upper and already he could feel the rain soaking in. It was falling harder now.

He breathed deeply. The light was extraordinary; the sky was split in two distinct halves. Over the sea hung huge black storm-clouds, rolling inland rapidly, but over the hills behind the town there was a wide, gentle expanse of blue, with filmy white and pink clouds scudding restlessly along. The sun was just hidden from Matthew by the edge of the storm-clouds, but the cliffs towards which he was heading, outside the town, shone gold and white in its rays, and the crashing waves at the foot of the cliffs sparkled a distant brilliant green.

Matthew jumped down the slope of the concrete front to the shingle four feet below, and picked up one of the pebbles and put it in his pocket. He had no idea why he did this. It was an impulse. The whole thing was an impulse. The storm that was coming was undoubtedly an impulse in the heart of God.

Matthew was twenty-three years old. He was a little over medium height, and slightly built; he had a dark complexion, and his hair was black and long. His eyes were brown, and rounder than most people’s, which gave them the appearance of staring wildly and nervously. His hands trembled.

When the stone was safely in his pocket he scrambled back on to the pavement above the beach and strode off again. The storm-clouds had spread much further and there was now very little blue sky left over the hills. The cliffs no longer shone in the sun.

The town was not large, and in any case most of it lay behind him. To the right, as he looked along the road, the beach stretched along to the cliffs, and on his left was a row of boarding-houses and small hotels very like the one he was staying in. They looked like mock-Regency and were mostly painted white or light grey, though the paint was peeling on some of them. The air, fluid and dark though it was, somehow held a livid kind of light in suspension, and the white-painted houses seemed to attract it electrically and glow in the stormy semi-darkness. The first peals of thunder rolled, far out to sea, and Matthew felt a lump in his throat. He felt like a cat prowling and he also felt an unbearably tense longing for a climax to days of waiting, for a sign from – where? From God, he supposed; and for emotional and mental and sexual relief. He felt like the world itself preparing for war.

He came to a car-park at the end of the sea-front, where the road turned away from the beach. The mock-Regency houses here gave way to smaller and less grandiose semi-detached houses and shops selling buckets and spades and postcards. The car-park marked the limit of the sea-front, though a line of beach-huts stood on the far side of it. Behind them were sandhills; and behind them, grassy fields that led up to the heights of the cliff-tops.

Matthew went into the car-park and stood still for a moment. He looked around, feeling that the place was thronged by the ghosts of holiday-makers; there were only two cars there, but the car-park seemed crowded. He stared over the tiled house-tops and chimney-pots at the last remnant of blue in the sky. Something in the shape of it and in the light on the roof-tops and in the rain and wind and the clouds behind him spoke all at once, and confusedly and dreamily but with great power, of extraordinary and unfathomable romance; and then it was gone, and Matthew stood emptily, not understanding.

He walked slowly across the car-park, and then turned back to see if anything of the feeling remained. It did, but he could not say why or what it was, or where it came from. Most of it, he supposed, was a longing in himself. He turned his back on it.

There was a barbed-wire fence around the car-park, and when he came to it he paused, wondering how to get through. He noticed, looking along it, that the corner nearest the beach was broken and lay sideways, and went along and climbed over the twisted strands. An old rusty petrol tin lay half-buried in the sand by the corner post; empty cigarette-packets and sheets of torn newspaper littered the sand. The look of it pleased Matthew, for there was an ugly and discordant and careless poetry in it. It was the same with rows of badly-planned houses, and factories on the edge of towns, and oil refineries on the coast. There was beauty there, but it was harsh and even unpleasant: and to Matthew, it was worth more than most things.

His overcoat was soaked. The sand was getting into his shoe, so he moved, and went into the field behind the sand hills. It was used by campers in the summer. There were a few caravans parked near the road, and next to them was a garage. The lights were all on inside it. The few cars that passed, he noticed, had their sidelights on. He would have to hurry to get to the cliffs before dark.

He walked quickly through the first field and into the second, and through that, and then the fields gave way to a rough grassy, area with gorse-bushes growing here and there, that led gradually to the cliff-tops. There was no-one in sight, and the road was far enough away not to matter, and the cliff-tops were ahead of him, so the way was clear. Anything could happen. He prayed with all his heart that something would.

He had prayed for it all day long in the stuffy hotel. He had sat since breakfast in the lounge, forcing himself to be still, not to get up and walk about, and promising himself that he would go outside later, when he felt calmer. Halfway through the morning he had to go to his bedroom and lie down, for the tension in his right temple was making him feel sick. Then the nausea passed; he ate lunch slowly and went back to the lounge and sat down again. He stared out of the window, over the beach, and felt relief of a sort as he watched the storm building up late in the afternoon. He had hardly seen anyone pass by. The town was nearly dead at this time of year. The day was cold, but oppressive, with hazy clouds and hazy sky. He held back until the first spots of rain fell on the window; then he went to get his overcoat, and set out.

He stumbled across the rough grass, hurrying so as to get there before dark, the rain falling thicker and the thunder rolling more closely now. Why did he want to get there before dark? What did he want to see? Anything.

The light, however, instead of fading, seemed to be getting greener and more diffuse; it attached itself to things at random, accentuating their outlines and giving them an extraordinary significance. A patch of sand on one of the dunes to his right; a gorse bush ahead of him. They glowed fiercely and tempted him to go up to them and lie close to their light, to study himself by it, to look at his hands and his arms and legs, to talk to himself. No! He strode onwards. First to the cliffs, and then…

A flash of lightning and then – he counted – five seconds afterwards, the thunder. The slope was rising now, and the dunes thinning out. He must be opposite the spot where the rocks began on the beach. His feet had found a path up the slope, but, noticing how slippery it was, he walked beside it. He went nearer the edge. Further up there was a fence along the top, but here the cliff was not high enough to need it and in any case the slope down to the beach was gentle. He stopped for a minute and looked across at the sea. The sandhills, lashed by the rain, lay in front of him, the coarse spiky grass clinging to the sides of them like long dark hair. Over their tops he could see the line of the Spur. The Spur was a long stretch of rock that led off the beach at right angles, like a jetty. It was uncovered at low tide, and in the summer children played on it with nets; now the waves were racing up the length of it and across, smashing luminously. The tide was nearly at its height.

Matthew was shaken suddenly by a sob, of rage as much as anything else, and clenched his fists, his

arms straight down by his sides, staring out to sea. The black clouds seemed to have come much closer, so that there were no precise limits to the air and the water. The abnormal light under the clouds showed up the confused medley of elements out at sea in detail that shifted and changed too fast for Matthew to grasp it. Each wave was outlined brightly in foam, and the foam itself was outlined on the water by a line of tiny bubbles larger than the rest – Matthew was sure of this, though he could see no wave distinctly; but his own limits were as indistinct as those of the sky and the sea, and what he knew and what he did not know were shaken together like sand, and were hurled away with the storm like broken habits.

He broke into a run further up the cliff. He came to the fence, a stout wooden one set firmly in the turf, and leant against it for a moment, breathless, and panting with difficulty in the snapping, tearing wind. It was blowing much more fiercely up here. He put both hands on the top rail of the fence and shook it hard. He hit it with the palm of his right hand and shouted wordlessly into the air. He shouted at the top of his voice but heard nothing over the wind and the waves. He peered over the fence and over the edge of the cliffs a few feet beyond, but saw only the surging water crashing against the side of the Spur.

He sobbed again, and felt his eyes grow dim and hot with tears. He climbed swiftly over the fence and walked forward, stopping abruptly at the edge. The wind made him sway, but he took no notice; he was lost for a moment, weeping uncontrollably. After a minute he started to move again, climbing further up the cliffs, but keeping to the extreme edge. Once or twice he slipped on the streaming grass but recovered himself casually, without thinking.

He did not pause until he had come, stumbling blindly, to the highest point of the cliffs; and here he stopped and faced the sea, and forced himself to be still, and to listen and watch. The water raged beneath him with no pattern in its tumult. The waves did not fall one after the other in a regular rhythm, but hastened together, each engulfing the others, and all of them reaching angrily for the land. The noise of them had no bounds, it filled the air completely, washing against the borders of the world, with such a roar that the crashes of thunder could hardly be heard. On top of this was the deep-throated clatter of million upon millions of pebbles, tumbled around by the water, and the howling of the wind. With only a little effort Matthew could hear voices in the wind, fragments of words and cries and sentences, thousands of lost voices tossed over the endless sea and drowned; and with a similar slight effort he could see, in the surging tumult of the sea and the sky, innumerable ghosts and shattered figures, beckoning and calling. Their arms and fingers reached out in the spray, and they were dragged under by the weight of the waves behind them; and others took their place, like the shingle, numberless, in the water or in the air, in the spray or in the darkening clouds. The light by which he saw seemed to come from nowhere, as if it had wandered into the world from outside and stayed, trapped under the pall of cloud and murky water; and there seemed to be panic in it, for it moved in constantly between the white foam on the water and the lightning in the sky, fluttering like a caged bird, desperate to return to its original source and escape the haunted storm of the world.

Matthew watched all this while standing quite still, maintaining his balance in the wind; and he was unconscious of the drop only a couple of feet in front of him, for he knew that something in his head was coming to a crisis. There was a throbbing tension in his right temple which might at any moment turn into a blinding headache. This headache came to him from time to time and inevitably prostrated him, and all his actions that day had been directed among other things towards avoiding it. He had discovered that if he went carefully, and followed every whim, and tried to propitiate it, it sometimes did not appear. The throbbing in his temple was a warning that it was due; he had woken up with it, and had gone carefully all day to avoid jarring it into pain. It was this which had led him to the top of the cliffs, either to jump off or fall off or go home cured – this, and a nearly frenzied longing for knowledge, for a sign out of the storm.

Then the throbbing increased and the first filaments of pain began to burn in Matthew’s head; he shut his eyes and, on another impulse, raised his right hand and stretched his fingers out to the sky, and prayed for lightning to strike him dead.

But none came; and presently, to his astonishment, the pain subsided, and the throbbing died away, leaving him clear and light-headed for what seemed like the first time for days.

He stepped back from the edge, dizzy, and lay down weakly on the grass. The rain beat at his face and streamed over the length of his body, and he shivered with cold, but at least his head was clear. He considered his position.

He could go back to the hotel and do nothing; or he could stay lying ·on the grass until he fell asleep; or he could stand up and try to get down to the beach and walk for a while beside the raging sea. On the whole the last idea seemed the best, he thought. He got to his feet and tightened the belt of his coat.

He was still a little dazed from the relief of losing his headache. Nevertheless as soon as he began to move along the cliffs he almost regretted it, because by being in the forefront of his attention it had at least dammed other things back. Now, with it gone, there was nothing to restrain them, and they came flooding through. Prominent among them was the desperate longing for an unmistakable signal from God. From God, or the Devil, or any other interested party – as long as it proved that the universe had depth, and width, and significance, and that Matthew’s life partook of them. Also among the various fevers that shook his mind were a wide, impartial lust, a fear for his future, and, not least, a thin, maniacal glee that he had survived so far.

Armed and driven onward by these feelings, Matthew looked for the footpath that ran along the top of the cliffs, and, having found it, set off along it as fast as the rain and the slippery mud would let him. It must lead down eventually, he thought, to the beach; and he was right. Fifty yards or so along from where he had been standing, there was a fold in the cliff, and the path led straight towards the edge. Matthew thought it was going to plunge right over, but he found, hidden by the fold and shielded from the wind, a series of concrete steps leading down the cliff, with a stout railing embedded in them. He had had no idea it was there. Perhaps the tide of the world had changed in his favour for a while.

Holding the rail tightly he set off down the path. The steps were streaming with water, but the rough concrete was not slippery. The sole of his right shoe was now gaping even wider.

The path followed a series of natural ledges downwards, taking the easiest way. At times it was completely exposed to the wind, which nearly flattened Matthew against the rock wall. The state of his mind – and he was able somehow to stand back and watch it – was fluctuating as wildly as the light and the wind. One minute he would be secure and half-enjoying everything, and the next a great rush of despair would seize his heart and nearly force him to his knees from sheer weakness. Then he would feel himself gripped by a wave of lust, pure cerebral lust with no object, and that in turn would give way to a huge emptiness, an echoing cavern of no-purpose. All the while he carefully picked his way down the steps, clinging tightly to the railing in case he should slip. He thought for an instant of how he had been standing a few moments before on the cliff-top, and shuddered. His head was filled and emptied in turn. Tears for his helplessness came to his eyes and rolled down his cheeks, mingling with the rain.

The bottom steps were covered in a drift of pebbles and rough soil from the base of the cliffs. He let go of the railing and stepped on to the beach, looking around. The beach sloped down sharply to the water, which was ten yards or so in front of him. The tide was almost at its height, and the waves crashed angrily with a roar that deafened him completely. They were high and fierce, and the water raced sideways after the waves broke, each retreating back into the belly of the next. He walked carefully down to the water, wiping the rain from his eyes, and stopped just where the highest rush of the water came. He c

ould feel the shingle moving underfoot as the great mass of water crashed down and swept back and sideways again.

The light was greener now, taking its colour from the water; and the clouds were universally black. The body of each wave was a trembling, translucent black-green, and the foam and the spray that shot far into the air were ghostly white. Further out were lighter patches on the water, patches of mud-green and what looked like yellow. The spray dashed into Matthew’s face, but he hardly noticed.

There was something moving out on the sea, and it was drifting in to the shore.

At first he was inclined to ignore it. But his eyes stayed on it and before long it had absorbed his interest to the point where he could not look away if he tried. Above the roar of the waves and the shingle he could hear, faintly and intermittently, the noise of an engine, but soon that stopped. The boat, meanwhile – for that was what it was – had drifted in further, and he could see lights on board, and even make out dimly the shape of it. It looked like a fishing boat of some kind, with a small wheelhouse amidships, where a light was glowing. It rose and fell heavily with the waves. It was being carried in almost languidly, and borne along to his right. He supposed that the engines had failed.

It was still two or three hundred yards offshore – it was hard to tell in the wild confusion of spray, and the extraordinary light – but it was definitely coming closer. Matthew, eyes fixed on it, began to stumble along the beach, following it. His feet slipped once or twice on the shingle, but he kept his balance. He could see someone in the wheel house, moving about unhurriedly. Probably there was nothing they could do. He thought he could see a dinghy hanging over the stern; why hadn’t they lowered it into the water and rowed safely ashore?

He came to a spot where the shingle gave way to a mass of rocks, and had to take his eyes off the boat to clamber over them. They were rough with limpets, but great clumps of seaweed made them slippery, and he had to go carefully. When he got back on to the shingle he ran a little way to catch up with the boat, stumbling and nearly falling head long, and panting with excitement. Something, either the boat itself or the sea, had gripped his emotions and was holding them tight. The world had come alive again, and in the sweep of the wind and rain he felt a hint of that mysterious romance which had emanated from the sky over the rooftops earlier on.