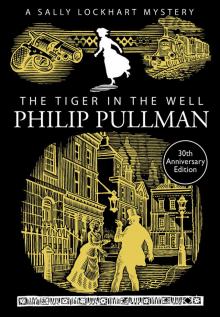

The Tiger in the Well

Philip Pullman

THE TIGER IN THE WELL

PHILIP PULLMAN

By Philip Pullman

The Sally Lockhart Quartet

The Ruby in the Smoke The Shadow in the North The Tiger in the Well The Tin Princess

His Dark Materials

Northern Lights

The Subtle Knife

The Amber Spyglass Lyra's Oxford

Once Upon a Time in the North The New Cut Gang

Thunderbolt's Waxwork The Gas-Fitters' Ball Contemporary Novels

The Broken Bridge The Butterfly Tattoo The Good Man Jesus and the Scoundrel Christ Books with Pictures and Fairy Tales

The Scarecrow and his Servant Spring-Heeled Jack Count Karlstein

The Firework Makers' Daughter I Was A Rat!

Puss in Boots

Mossycoat

Aladdin

Clockwork

Grimm Tales: For Young and Old Plays

Frankenstein (adaptation)

Sherlock Holmes and the Limehouse Horror

THE TIGER IN THE WELL

PHILIP PULLMAN

A SALLY LOCKHART MYSTERY

About the Author

Born in Norwich in 1946, Philip Pullman is a world-renowned writer. His novels have won every major award for children's fiction, and are now also established as adult bestsellers. The His Dark Materials trilogy came third in the BBC's "Big Read" competition to find the nation's favourite book. In 2005 he was awarded the Astrid Lingren Memorial Award, the world's biggest prize for children's literature. Philip is married with two grown-up children, and lives in Oxford.

"Stories are the most important thing in the world. Without stories, we wouldn't be human beings at all"

PHILIP PULLMAN

For Jude, with love

Contents

CERTAIN ITEMS OF HISTORICAL INTEREST 1881

BOOK ONE

Chapter OneTHE PROCESS-SERVER

Chapter TwoTHE JOURNALIST

Chapter ThreeTHE MARRIAGE REGISTER

Chapter FourTHE TAX-COLLECTORS

Chapter FiveTARGET PRACTICE

Chapter SixMIDDLE TEMPLE LANE

Chapter SevenTHE HOUSE BY THE CANAL

Chapter EightTHE KNIFE-MAN

Chapter NineTHE EMINENT QC

Chapter TenCUSTODY

BOOK TWO

Chapter ElevenVILLIERS STREET

Chapter TwelveTHE BANK MANAGER

Chapter ThirteenTHE TEA-SHOP

Chapter FourteenTHE GRAVEYARD

Chapter FifteenTHE MISSION

Chapter SixteenPLAYING WITH BRICKS

Chapter SeventeenJUST A MAN WORKING

Chapter EighteenTHE ORDER OF SANCTISSIMA SOPHIA

Chapter NineteenREBECCA'S STORY

Chapter TwentyHENNA

BOOK THREE

Chapter Twenty-oneTHE VALET

Chapter Twenty-twoTHE CELLAR

Chapter Twenty-threeNO JUWES

Chapter Twenty-fourTHE ENTRY IN THE LEDGER

Chapter Twenty-fiveTHE BATTLE OF TELEGRAPH ROAD

Chapter Twenty-sixBLACKBOURNE WATER

Chapter Twenty-sevenTHE TIGER IN THE WELL

Chapter Twenty-eightINDIAN INK

Chapter Twenty-nineRABBITS

Chapter One

THE PROCESS-SERVER

One sunny morning in the autumn of 1881, Sally Lockhart stood in the garden and watched her little daughter play, and thought that things were good.

She was wrong, but she wouldn't know how or why she was wrong for twenty minutes yet. The man who would show her was still finding his way to the house. For the moment she was happy, which was delightful, and she knew she was, which was rare; she was usually too busy to notice.

She was happy, for one thing, about her home. It was a large place in Twickenham called Orchard House - a Regency building, open and airy, with iron balconies and a glass-roofed veranda facing the garden. The garden itself, enclosed by a mellow brick wall, consisted of a wide, sunny lawn with some flower-beds and a vine and a fig-tree against the wall on one side, and the group of old apple and plum trees at the bottom which gave the house its name.

Against the wall on the side opposite the fig-tree a curious structure had been built: glass-roofed like the veranda, but open all the way along, and containing what looked like the track for a large model railway, supported on trestles about three feet high. It had been built to shelter some experiments in the photography of motion, and there was more work to do on it, but it would wait until her friends came back.

Her friends: she was happy in her friends. Webster Garland, sixty-five, a photographer and her partner in Garland and Lockhart, the firm that joined their names, and Jim Taylor, at twenty, two or three years younger than herself, were all she had for a family. They shared the house, they'd shared adventures; they were Bohemian, they were unrespectable, they were staunch and faithful, and at the moment they were in South America. Every few years, Webster Garland gave in to the urge to wander into some wild part of the world and photograph it. This time, Jim had gone with him; so Sally was on her own.

But not really alone. There was the staff - and that was something else she was happy with - Ellie the maid, and Mrs Perkins the cook-housekeeper, and Roberts who looked after the garden and the horses. And there was the photography shop in Church Street, where she went once a week to look over the accounts. And there was her own business in the City: a financial consultancy which she'd built up successfully against the expectations of everyone who thought that women couldn't do that sort of thing, or shouldn't if they wanted to remain feminine, or wouldn't if there wasn't something wrong with them. She'd become so busy that she'd recently had to take on a partner: a dry, ironical young woman called Margaret Haddow, a graduate and a feminist like herself. And, finally, there was the nurse she'd engaged to help her with the child: Sarah-Jane Russell, eighteen, competent, kindly, and in love (without his knowledge, or anyone else's) with Jim Taylor.

But the centre of all this happiness was the child. Harriet was a year and nine months old: autocratic, wilful, and so solidly sure of everyone's love and attention that she gave off happiness herself as the sun gives off light. Her father, Frederick Garland, Webster's nephew, had never seen her, for he had died in a fire on the night she was conceived; and if he'd lived, Sally would be Mrs Garland, and Harriet legitimate. Sally's love for Frederick had been hard won and given without stint. What she felt for Harriet was as deep as her blood, as deep as her life itself. She'd never loved anyone or anything as much, never known it was possible. At first, after Frederick's death, when their business lay in ruins, she felt she didn't want to live, but when she felt the stubborn life inside her she knew she did, and knew she must. And apart from the terrible gap that Frederick had left, life was good now - as good as it ever could be for an unmarried mother in Queen Victoria's time; better by far than for plenty of women trapped in unhappy marriages. She had money and independence and friends, and a home, and interesting work, and she had her precious Harriet.

She plucked two figs, newly ripened, and took them over to the orchard. Sarah-Jane was sitting on the tree-seat Webster had built, sewing something, while Harriet was helping her toy bear Bruin climb a rope to get some imaginary honey. Sally joined Sarah-Jane on the seat.

"D'you like figs?" she said, handing her one.

"I love them," said the nurse. "Thank you."

Sally could see past the side of the house to where someone was consulting a paper at the front gate. He opened it and came through, moving out of sight as he made for the front door.

"Hattie-face, come and share the fig," she said.

Harriet, seeing food, dropped Bruin and came at once. She looked suspiciously at the soft red flesh packed with tiny seeds. Sally t

ook another bite.

"Like this," she said. "If you don't try it, you won't know what it's like. Bruin will have some."

They fed Bruin, and then Harriet nibbled the fig, and then she wanted all the rest.

"She's growing so fast," said Sarah-Jane. "Look, I can't turn these petticoats down any more. They'll do this time but then she'll need new ones."

"We ought to measure her," said Sally. "Draw a line on the wall. Shall we do that, Hattie? See how tall you're getting?"

"Fig," said Harriet accusingly, holding out her hand for Sarah-Jane's. "Fig, please."

Sally laughed. "No, that's Sarah-Jane's. Look, here comes Ellie with a visitor."

Harriet, proprietorial, turned to see who had come to pay court to her this time. Ellie was making her way down the lawn, followed by the man from the front gate. He was slight and middle-aged, as far as Sally could tell, and he wore a shabby brown suit and bowler hat. He was holding a large white envelope.

"Miss Lockhart," said Ellie uncertainly, "this gentleman says he's got to see you in person, miss."

The man raised his hat. "Miss Lockhart?"

"Yes?" said Sally. "What can I do for you?"

"I am under instructions to give this into your hands, miss."

He held out the envelope. Sally saw a red legal seal on it. Automatically she took it from him. It's very hard not to take things people hand you; politeness is an easy thing to take advantage of.

The man doffed his hat again, and turned to go. Sally stood up.

"Wait, please," she said. "Who are you? And what's this?"

"It's fully explained inside," he said. "As for me, I'm a process-server, miss. I've done my duty, and now I must be on my way, else I shall miss my train. Beautiful weather for the time of year. . ."

With a nervous little smile, he turned and set off back up the garden. Ellie, after a troubled glance at Sally, hastened after him.

Harriet, disappointed in the visitor's poor taste, turned back to Bruin and the honey. Sally sat down. She was conscious that she might have made a mistake in accepting the envelope so tamely: couldn't you refuse to accept a summons, or something? Didn't you by accepting it admit that there was a case to answer. . .? Oh, it was bound to be nonsense anyway. Someone had made a mistake.

She tore open the thick paper and pulled out a long, carefully folded document. The Royal Arms was embossed at the top, and paragraph after paragraph of legal copperplate stretched out below. Sally began to read.

It was headed In the Probate, Divorce and Admiralty Division of the High Court, and it began:

On the 3rd day of January, 1879, the petitioner, Arthur James Parrish, was lawfully married to Veronica Beatrice Lockhart (hereinafter called "the respondent") at St Thomas's Church, Southam, in the County of Hampshire.

Sally gave a little gasp. This was ridiculous. Veronica Beatrice was her own name - one she'd never answered to since, a strong-willed child like Harriet, she had informed her father that she was Sally, and refused to answer to anything else. But . . . married? Someone was claiming to be married to her?

She read on:

The petitioner and respondent last lived together at 24, Telegraph Road, Clapham.

The petitioner is domiciled in England and Wales, and is by occupation a commission agent, and resides at 24, Telegraph Road, Clapham, and the respondent is by occupation a financial consultant, and resides at Orchard House, Twickenham.

There are no children of the family now living except Harriet Rosa. . .

Sally put the paper down.

"Oh, this is stupid," she said. "Someone's playing a joke."

Sarah-Jane looked up. Sally saw the question in her face.

"I'm being sued for divorce," she said, and then laughed. But it was a short laugh, and Sarah-Jane didn't smile.

"It's an expensive joke for someone to play, going to all those lengths," she said. "You'd better read the rest of it."

Sally took up the paper again. Her hands were trembling. She read on with increasing disbelief through several more paragraphs of legal language, and came to a long section headed Particulars.

It was easy to follow, next to impossible to take in. It related the story of a marriage that had never existed; it told how Sally and this Mr Parrish had married, settled in Clapham, had a child, Harriet (whose birthday, at least, was accurate); how Sally had persistently and wilfully treated her "husband" with cruelty, his business associates with scorn and their guests with contempt, until he found it impossible to bring anyone home and be sure she would receive them in a decent and civil manner; how she had taken to drink, and appeared drunk in public on more than one occasion (details provided, witnesses named); how she had mistreated the servants, forcing three separate maidservants to leave without notice (names and addresses provided); how she had misused the money her "husband" had settled on her, and insisted against his wishes on setting up in business on her own; how he had attempted to reason with her, and live with the situation, and treated her with every consideration; how, shortly after the birth of their child, she had deserted the family home, taking the child with her; how she was not a fit person to have custody of the child, because she was currently associating with persons of doubtful morality, sharing a household with two unmarried men (names provided); and there was more. There were five closely written pages, but she had to push the document away after scanning only two of them.

"I don't believe it," she said, hardly in control of her voice. She thrust the paper at Sarah-Jane and stood up blindly. While Sarah-Jane looked at it, Sally walked to the end of the orchard, plucked a twig off the apple tree, and shredded it to pieces. She felt as if someone had crept into her life and befouled everything in sight. That anyone could write such a pack of filthy lies about her - but it was impossible. She couldn't take it in.

There was worse to come. She heard Sarah-Jane gasp, and turned quickly.

Sarah-Jane was holding out the last section of the document. It was headed Prayer.

Sally took it and sat down. She felt unable to stand.

The page read:

The petitioner therefore prays:

That the said marriage be dissolved.

That the petitioner be granted the custody of the child, Harriet Rosa, with immediate effect.

That -

It was enough. Sally wanted to read no more. Someone, someone unknown, this Parrish, a liar, a madman, wanted to take her child away from her.

Only a few yards away Harriet sat on the grass, teasing out the end of a piece of old rope Webster had given her and seeing how it wanted to twist together again. Bruin lay forgotten beside her. She was utterly absorbed, concentrating fiercely on the extraordinariness of things like rope. Sally got to her feet and ran to her and caught her up in a hungry embrace, aware of her own strength and trying not to hurt her, but wanting her as close as she could get.

Harriet submitted to it patiently; embraces had to be put up with. Finally Sally let her go and kissed her, and put her gently down on the grass again. Harriet picked up the rope and carried on.

"I'm going to the city," she said to Sarah-Jane. "I've got to take this to my solicitor. It's nonsense, of course. The man's mad or something. But I must see him at once. The case is -"

"A fortnight," Sarah-Jane said. "In the Royal Courts of Justice. That's what it says."

Sally took up the document. She didn't like touching it. She put it back in the envelope and kissed Harriet once, twice, three times again, and went to get ready for the train to London.

Sally's solicitor, Mr Temple, an old friend of her father's who'd helped her set up in business, had died the year before. The leading partner in the firm was now a Mr Adcock, whom she did not know very well. She didn't much like what she did know; but she couldn't afford to think of that. He was a smooth, youngish man, who was the sort of person so anxious for the approval of his elders that he aped their opinions, their manners and their fashions. Mr Temple had taken snuff; in him it had seemed natural. Mr Adcock

did too, but in him it seemed affected. Sally of course hadn't seen him in his club, but if she had, she'd have raised her eyebrows at the conservatism of the views he expressed - and at the fact that they became more loudly expressed, and more conservative, when any distinguished elderly member was near by.

When Sally arrived at his office he was busy with another client, and she sat with the old clerk, Mr Bywater, who'd served the firm for fifty years. He knew her business better than Mr Adcock did, and she was so much on edge that she couldn't help telling him what she'd come about. He sat, ancient and impassive, while she told the whole story. She feared his sharp tongue; but - she felt better when she'd finished.

"Dear oh dear," he said. "Why didn't you tell Mr Temple about the child?"

"Because. . . Oh, Mr Bywater, you can imagine, can't you? He was ill. And I was fond of him. I didn't want to lose his good opinion."

"His good opinion was based on your sense," he said, "not your sanctity. You should've told him. You made a will? Thought not. Who's that fellow's solicitors? Grant, Murray and Girling. Hmm. See what I can find out. I think Mr Adcock's ready for you now."

He cocked his head, listening, and then opened the door and announced her.

Mr Adcock was all smooth affability. This is a purely professional relationship, she reminded herself; he's a solicitor, he's trained in the law, never mind his manner.

She went through the facts as clearly as she could, starting with Harriet. Mr Adcock listened, his expression becoming graver by the minute. Occasionally he made a note.

"May I see the petition?" he said when she'd finished.

He read it through while she sat, composed, upright, trembling.

"These are very serious allegations," he said when he'd reached the end. "He alleges desertion, misuse of funds, drunkenness even. . . Miss Lockhart, may I ask you if you drink?"

"Do I drink? I take a glass of sherry sometimes, but what on earth does that matter?"

"We have to be sure of our ground. These servants, for instance, whose dismissal is complained of: if we could establish precisely what happened, we could construct a sound defence."

Sally felt a shiver of dismay. "Mr Adcock, there weren't any servants. There never was a household in what-is-it, Telegraph Road, Clapham. I never was married to this Mr Parrish. The whole thing is a fabrication. He's made it all up. It's a huge lie."