Mirror Kingdoms: The Best of Peter S. Beagle

Peter S. Beagle

Copyright © 2015 by Avicenna Development Corporation. All rights reserved. Published in the United States of America by Conlan Press, Inc. First published in 2010 by Subterranean Press. All current copyrights in the content are owned by and appear by permission of Avicenna Development Corporation.

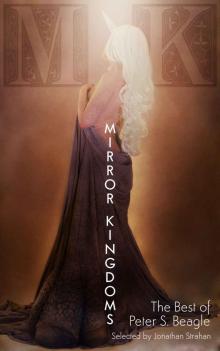

The cover photo is by Sarah Allegra and is used by permission. Cover layout and design by Connor Cochran.

Conlan Press Ebook Release: 1.0

Release Date: November 2015

www.conlanpress.com

ISBN-13: 978-1-62-294009-7

Introduction copyright © 2009 by Avicenna Development Corporation.

“Professor Gottesman and the Indian Rhinoceros” copyright © 1995 by Peter S. Beagle. First published in Peter S. Beagle’s Immortal Unicorn, edited by Peter S. Beagle and Janet Berliner (HarperCollins: New York).

“The Last and Only, or, Mr. Moscowitz Becomes French” ©2007 by Peter S. Beagle and Avicenna Development Corporation. First appeared in Eclipse One, edited by Jonathan Strahan (Night Shade Books: San Francisco).

“Come Lady Death” copyright © 1963, renewed 1991, by Peter S. Beagle. First appeared in The Atlantic Monthly, September 1963.

“El Regalo” copyright © 2006 by Peter S. Beagle. First appeared in The Line Between (Tachyon Publications: San Francisco).

“Julie’s Unicorn” copyright © 1997 by Peter S. Beagle. First appeared in The Rhinoceros Who Quoted Nietzsche and Other Odd Acquaintances (Tachyon Publications: San Francisco).

“The Last Song of Sirit Byar” copyright © 1996 by Peter S. Beagle. First appeared in Space Opera, edited by Anne McCaffrey and Elizabeth Ann Scarborough (DAW: New York)

“Lila the Werewolf” copyright © 1971 by Peter S. Beagle. First appeared in New Worlds of Fantasy #3, edited by Terry Carr (Ace Books: New York).

“What Tune the Enchantress Plays” copyright © 2008 by Avicenna Development Corporation. First appeared in A Book of Wizards, edited by Marvin Kaye (Science Fiction Book Club: New York).

“Uncle Chaim and Aunt Rifke and the Angel” copyright © 2008 by Avicenna Development Corporation. First appeared in Strange Roads by Peter S. Beagle (DreamHaven Books: Minneapolis).

“Salt Wine” copyright © 2006 by Peter S. Beagle. First appeared in Fantasy Magazine, May 2006.

“Two Hearts” copyright © 2005 by Peter S. Beagle. First appeared in The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction, October/November 2005.

“Giant Bones” copyright © 1997 by Peter S. Beagle. First appeared in Giant Bones (Roc: New York).

“King Pelles the Sure” copyright © 2008 by Avicenna Development Corporation. First appeared in Strange Roads by Peter S. Beagle (DreamHaven Books: Minneapolis).

“Vanishing” copyright © 2009 by Avicenna Development Corporation. First appeared in Orson Scott Card’s Intergalactic Medicine Show, March 2009.

“The Tale of Junko and Sayuri” copyright © 2008 by Avicenna Development Corporation. First appeared in Intergalactic Medicine Show, July 2008, edited by Orson Scott Card.

“The Rock in the Park” copyright © 2010 by Avicenna Development Corporation. Derived from an original podcast performance recorded for The Green Man Review (www.greenmanreview.com) copyright © 2008 by Avicenna Development Corporation. First appeared in print in Mirror Kingdoms: The Best of Peter S. Beagle, edited by Jonathan Strahan (Subterranean Press: Burton).

“We Never Talk About My Brother” copyright © 2007 by Peter S. Beagle and Avicenna Development Corporation. First appeared in Orson Scott Card’s Intergalactic Medicine Show, July 2007.

“The Rabbi’s Hobby” copyright © 2008 by Avicenna Development Corporation. First appeared in Eclipse Two: New Science Fiction and Fantasy, edited by Jonathan Strahan (Night Shade Books: San Francisco).

For Victoria and Jack Knox, Kalisa Beagle and Farhad Torkamani, Dan and Robin Beagle, my family.

MIRROR KINGDOMS:

THE BEST OF PETER S. BEAGLE

By Peter S. Beagle

Stories selected by Jonathan Strahan

CONTENTS

Introduction

Professor Gottesman and the Indian Rhinoceros

The Last and Only, or, Mr. Moscowitz Becomes French

Come Lady Death

El Regalo

Julie's Unicorn

The Last Song of Sirit Byar

Lila the Werewolf

What Tune the Enchantress Plays

Uncle Chaim and Aunt Rifke and the Angel

Salt Wine

Two Hearts

Giant Bones

King Pelles the Sure

Vanishing

The Tale of Junko and Sayuri

The Rock in the Park

We Never Talk About My Brother

The Rabbi's Hobby

INTRODUCTION

What strikes me most immediately, looking over the table of contents of this book, is the obvious and remarkable gap between the two earliest and everything else. “Come Lady Death” first saw print in the Atlantic Monthly in 1963, though it had been written a couple of years before, while “Lila the Werewolf” was originally published in Terry Carr’s New Worlds Of Fantasy #3 in 1971, then reprinted as a chapbook by Capra Press in 1974. And except for a couple of non-fantasy stories I’d written for college classes and published in my teens, that was absolutely it for me and short fiction until 1994.

I have excuses. I worked on one novel, The Folk of the Air, through eighteen years and four separate versions; and I was constantly diverted during that stretch by movie and TV gigs, which paid me far more money than I’d ever seen, even though precious little of what I wrote ever made it to the screen. And then I wrote another novel, The Innkeeper’s Song, which was published in 1993. But in looking back, the real reason for the complete lapse in my short-story production strikes me as the fact that I was simply afraid of the form. There’s probably a Latin term for the phobia; I’ll have to look into it.

To me, short stories have always ranked with poetry as the most difficult of literary forms, primarily because the writer can’t afford to make a single mistake. One broken rhythm—one missed moment of revelation, one wrong word or line of dialogue—and it’s all over: the trick revealed, the illusion of magic gone. Novelists have it easy, by comparison, unless you’re someone like Vladimir Nabokov, who is writing poetry. The rest of us can make every stylistic and technical error in the book and still get away with beating the reader into submission with detail, character, or plain action. (I offer Theodore Dreiser as the ultimate poster boy in this regard.) As the film director Michael Curtiz said when it was pointed out to him that a particular Errol Flynn movie lacked any logic in its development, “Don’ worry—I make the sonabitch move so fast, nobody notice.” He did, too, and so do we. Often.

Also, I’m a comparatively slow writer, with a distressful tendency to make things up as I go along. I felt that as much time and effort as a story cost me, I might just as well be working on a novel. So this sudden explosion of short fiction between 1994 and the present is hard to explain, even to myself. Both “Professor Gottesman and the Indian Rhinoceros” and “Julie’s Unicorn” (the former remains my personal favorite still) were written specifically for a two-volume anthology of unicorn stories called Peter S. Beagle’s Immortal Unicorn (largely edited, in all candor, by Janet Berliner; I mainly committed my stories and some introductions to the enterprise, and let my name be added to the title to satisfy the publisher’s marketing imperative). Then my old friend Annie Scarborough cozened me into writing “The Last Song of Sirit Byar” for Space Opera, a collection of fantasy stories based around vocal music, which she co-edited with Anne McCaffrey. “Sirit Byar” was a

return to the world I invented for The Innkeeper’s Song, and it set me off on writing a series of five related stories, which became the collection Giant Bones (a.k.a. The Magician of Karakosk in every foreign edition, and in the upcoming American reprint.) All of these were written in the mid-1990s, and I’m still very proud of them.

But the real flood starts in 2004, with “Two Hearts,” the tailpiece or coda to The Last Unicorn. Connor Cochran, my business manager, de facto agent, accountant, chauffeur, first reader and editor, and all-purpose accomplice, persuaded me to write it, just as he is responsible, in one way and another, for the existence of all the stories that followed. Two Hearts itself exists because Connor noodged me into creating a bonus gift of a new story for the first 3,000 people to order the CD of the audiobook of The Last Unicorn. “You don’t even have to use any of the same characters—that world must have plenty of other stories in it,” he said in response to my initial refusal. So, naturally, I wound up writing the quasi-epilogue I did, which inevitably became a bridge to a true sequel novel that I am now working on. This happens a lot.

My tales tend to run long, often falling into the more or less arbitrary novelette or novella category: ironic for someone whose short-story idols include Chekhov, John Collier, Saki, Avram Davidson, Jessamyn West and Eudora Welty. I attribute this to my pattern of taking forever to find out what the hell I’m doing, and what the story’s really about. (Connor calls me the King of the Second Drafts; but “The Tale of Junko and Sayuri” went through seven passes, and both “What Tune The Enchantress Plays” and “Vanishing” hit twelve. I can think of one that took me a good sixteen, but it’s not in this collection, and I’ll never tell which one it is when it does appear.) The novelette length suits me in many ways: it leaves me room for digression—for what someone called “incidental felicities”—to move around and make discoveries, to take my time letting the tale unroll, and above all to surprise myself, which is crucial, whether you’ve got it all plotted and charted from the beginning or, like me, you’re fumbling around trying to trick the story into telling itself. All of that time and effort invested so that someone can later tell you, meaning to praise, that the story seemed to have flown out of you in one smooth burst of inspiration. If I hate one word in this world….

I don’t think of my fiction as notably autobiographical, except as all writers cannibalize our lives—just as we do other people’s—for the odd episode, memory or insight. (I See By My Outfit, my nonfiction book about a cross-country journey on motorscooters, is still occasionally taken as a novel to this day.) We use what comes in useful, however we may dress it up after the fact. “Giant Bones,” while an Innkeeper’s World fantasy, unquestionably draws its—okay, okay!—inspiration from affectionate recollection of a small boy named James, who wanted desperately to grow up to be six feet, seven inches tall, weigh two hundred and forty pounds, and play football. Damn kid used to drive me crazy, swinging from the lintel of every door in my house, trying to stretch himself. (He’s six-three now, and surfs.) Then there’s “Uncle Chaim and Aunt Rifke and the Angel,” which draws consciously and heavily on my New York childhood as the nephew of three Russian Jewish painters; while “The Rock in the Park,” one of five stories I wrote and recorded as podcasts for The Green Man Review website, goes back even more specifically to my old Bronx neighborhood, and employs my oldest friend as a character. In that sense, at least, I have been able to go home again, and I’m increasingly grateful for it as the years pass.

From my earliest childhood, I have spent a great deal—perhaps a majority—of my time in this world in the company of imaginary friends. A lady once tapped my head and said, rather sadly, “All those people partying up in there, and I’m not invited.” I explained, as best I could, that I’m not always invited either, and that I often end up crashing the party, or eavesdropping through doors, walls, windows. They rarely confide in me, my characters, but they do leave trails of breadcrumbs for me to follow.

In short stories, you don’t get much time to hang out with your imagined cast of characters: to have a beer and talk, to let them divulge, confide, let slip—and lie as well, for characters who lie will lie to their author, as they would to anyone else. I can be more confident in a novel, more assured that I’m in control, as I feel I really should be. But if these stories hold your interest, maybe it’s because with them I’m not assured, that I no more control what’s going on here than you do—and maybe less, because you can always close the book. On this side of the page it’s a bloody mosh pit, and I’m just doing my best to keep surfacing: writing for my life, and the lives and lies of my imaginary old friends.

—Oakland, California

2009

PROFESSOR GOTTESMAN AND THE INDIAN RHINOCEROS

Professor Gustave Gottesman went to a zoo for the first time when he was thirty-four years old. There is an excellent zoo in Zurich, which was Professor Gottesman’s birthplace, and where his sister still lived, but Professor Gottesman had never been there. From an early age he had determined on the study of philosophy as his life’s work; and for any true philosopher this world is zoo enough, complete with cages, feeding times, breeding programs, and earnest docents, of which he was wise enough to know that he was one. Thus, the first zoo he ever saw was the one in the middle-sized Midwestern American city where he worked at a middle-sized university, teaching Comparative Philosophy in comparative contentment. He was tall and rather thin, with a round, undistinguished face, a snub nose, a random assortment of sandy-ish hair, and a pair of very intense and very distinguished brown eyes that always seemed to be looking a little deeper than they meant to, embarrassing the face around them no end. His students and colleagues were quite fond of him, in an indulgent sort of way.

And how did the good Professor Gottesman happen at last to visit a zoo? It came about in this way: his older sister Edith came from Zurich to stay with him for several weeks, and she brought her daughter, his niece Nathalie, along with her. Nathalie was seven, both in years, and in the number of her there sometimes seemed to be, for the Professor had never been used to children even when he was one. She was a generally pleasant little girl, though, as far as he could tell; so when his sister besought him to spend one of his free afternoons with Nathalie while she went to lunch and a gallery opening with an old friend, the Professor graciously consented. And Nathalie wanted very much to go to the zoo and see tigers.

“So you shall,” her uncle announced gallantly. “Just as soon as I find out exactly where the zoo is.” He consulted with his best friend, a fat, cheerful, harmonica-playing professor of medieval Italian poetry named Sally Lowry, who had known him long and well enough (she was the only person in the world who called him Gus) to draw an elaborate two-colored map of the route, write out very precise directions beneath it, and make several copies of this document, in case of accidents. Thus equipped, and accompanied by Charles, Nathalie’s stuffed bedtime tiger, whom she desired to introduce to his grand cousins, they set off together for the zoo on a gray, cool spring afternoon. Professor Gottesman quoted Thomas Hardy to Nathalie, improvising a German translation for her benefit as he went along.

This is the weather the cuckoo likes,

And so do I;

When showers betumble the chestnut spikes,

And nestlings fly.

“Charles likes it too,” Nathalie said. “It makes his fur feel all sweet.”

They reached the zoo without incident, thanks to Professor Lowry’s excellent map, and Professor Gottesman bought Nathalie a bag of something sticky, unhealthy, and forbidden, and took her straight off to see the tigers. Their hot, meaty smell and their lightning-colored eyes were a bit too much for him, and so he sat on a bench nearby and watched Nathalie perform the introductions for Charles. When she came back to Professor Gottesman, she told him that Charles had been very well-behaved, as had all the tigers but one, who was rudely indifferent. “He was probably just visiting,” she said. “A tourist or something.” The Professor was still ma

rveling at the amount of contempt one small girl could infuse into the word tourist, when he heard a voice, sounding almost at his shoulder, say, “Why, Professor Gottesman—how nice to see you at last.” It was a low voice, a bit hoarse, with excellent diction, speaking good Zurich German with a very slight, unplaceable accent.

Professor Gottesman turned quickly, half-expecting to see some old acquaintance from home, whose name he would inevitably have forgotten. Such embarrassments were altogether too common in his gently preoccupied life. His friend Sally Lowry once observed, “We see each other just about every day, Gus, and I’m still not sure you really recognize me. If I wanted to hide from you, I’d just change my hairstyle.”

There was no one at all behind him. The only thing he saw was the rutted, muddy rhinoceros yard, for some reason placed directly across from the big cats’ cages. The one rhinoceros in residence was standing by the fence, torpidly mumbling a mouthful of moldy-looking hay. It was an Indian rhinoceros, according to the placard on the gate: as big as the Professor’s compact car, and the approximate color of old cement. The creaking slabs of its skin smelled of stale urine, and it had only one horn, caked with sticky mud. Flies buzzed around its small, heavy-lidded eyes, which regarded Professor Gottesman with immense, ancient unconcern. But there was no other person in the vicinity who might have addressed him.

Professor Gottesman shook his head, scratched it, shook it again, and turned back to the tigers. But the voice came again. “Professor, it was indeed I who spoke. Come and talk to me, if you please.”

No need, surely, to go into Professor Gottesman’s reaction: to describe in detail how he gasped, turned pale, and looked wildly around for any corroborative witness. It is worth mentioning, however, that at no time did he bother to splutter the requisite splutter in such cases: “My God, I’m either dreaming, drunk, or crazy.” If he was indeed just as classically absent-minded and impractical as everyone who knew him agreed, he was also more of a realist than many of them. This is generally true of philosophers, who tend, as a group, to be on terms of mutual respect with the impossible. Therefore, Professor Gottesman did the only proper thing under the circumstances. He introduced his niece Nathalie to the rhinoceros.