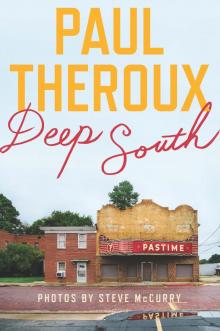

Deep South

Paul Theroux

Contents

* * *

Title Page

Contents

Frontispiece

Copyright

Dedication

Epigraph

Fall: “You Gotta Be Going There to Get There”

Be Blessed: “Ain’t No Strangers Here”

Wendell Turley

Road Candy: Traveling in America

The Mock Ordeal

Becoming a Traveler Again

Going South

The Submerged Twentieth

Dot Indians

Big Stone Gap

Gun Store

Asheville: “This We Call the Block”

“Who Am Ah?”

“Nu Man, Yanna Weep-Dee We Dan-Ya”

Route 301: “No One Ever Goes There”

Allendale County Alive

Orangeburg and the Massacre

Charleston: Gun Show

Reverend Johnson’s Story

Atomic Road

Believers on Bikes

Tuscaloosa: Football Matters

Sister Cynthia

The Cornerstone Full Gospel Baptist Church

The Black Belt

“Ah Mo Buy Me Some Popcorn, Set Me Down, and Watch the Show”

“White Privilege”

Mary Hodge: The Burning

Gathering Pecans

Greensboro: Mayor Johnnie B. Washington

Well-Wishers

The Horseshoe Farm After-School Program Competition Chart

“Our Own Matlock”

Reverend Eugene Lyles, Barber

The Klan in Philadelphia

Last Days on Gum Street

Bank Deserts

Natchez Gun Show

Mrs. Robin Scott: “To Save My Children”

The Delta: The Round Table

Delta Autumn

“Things Are Worse Than They Look”

“Jesus Is Lord—We Buy and Sell Guns”

The Taboo Word

Winter: “Ones Born Today Don’t Know How It Was”

Ten Degrees of Frost

Lumberton

Back Roads

Sunday Morning in Sycamore

“We Love You—Ain’t Nothing You Can Do About It!”

Lucky

“The Future Is a Faded Song”

The Inevitable Mr. Patel

Off the Grid

The Rosenwald Gift

Miss Cotton Blossom

“Ones Born Today Don’t Know How It Was”

“Our Randall Curb”

Hero of Greensboro

“Reason for Visit”

“Black Day”

Delta Winter

The Ghostliest Structure in the South

“People Are Buying Guns That Never Wanted No Guns”

Rowan Oak

Tupelo Blues

Bluegrass

The Paradoxes of Faulkner

Spring: Redbud in Bloom

Mud Season

Steeplechase in Aiken

The Secret Life of a Segregationist

The Bomb Factory: Mutant Spiders

A Glimpse of Wrens

Deep Trouble at the House of Love: “Accused Means Guilty”

Sermon with a Subtext: “What Would I Do Without My Storm?”

Cresent Motel

Saying Grace

Razor Road

Flowers Lane

The Fall

Vernell Micey

Pawnshop

“Bleeding Like a Hog”

Paralyzing Despair

“Limbic Resonance Is What You Need”

The Fantastications of Southern Fiction

Summer: The Odor of Sun-Heated Roads

Chasing Summer

Tunneling South

“They Took Mah Teeth”

Last Days

Massoud: “I Make Curbstones”

Jesse: “Everyone Knows That Tingly Feeling Goes Away”

Buddy Case: “You Couldn’t Say Nothing”

Alabama Traditions: The Segregated Sororities

Sandra Fair: “It’s Getting Worse”

Randall Curb: “My Wings Are Clipped”

Brookhaven—A Homeseeker’s Paradise

“Life Is a Highway”

Delta Summer

The Blues in Hollandale

Doe’s Eat Place

Sunday Morning in Monticello: Church, Catfish, Football

Hot Springs—Pleasures and Miseries

Road Candy at the Dixie Café

“There’s Some People Who Never Hit a Lick at a Snake and They Expect Help”

The Cabin on Quickerstill Lane

The Back Road to God’s Country

Deep-Fried Chocolate Pie

A Serious Row to Hoe

Working Poor

Roadkill

Jack-Jawin’: “Little Bitty Ole Meth Lab”

Old Testament Weather: “Baseball-Sized Hail”

The Arkansas Literary Festival

Buddy: “Be Careful”

Old Folks

Farmers on a Rainy Day

“Food Deserts”

“Sundown Town”

Buffalo River

“I’m In Too Deep to Quit”

“You Need a Tough Skin”

“If You Can Tell a White Farm from a Black Farm, You in Trouble”

An Agitator at Cypress Corner

Harvest

Lunch Under the Pecan Tree

“The Whole World Is a Family”

Chain Gang

The Valiant Woman in Palestine

Old Man

Deep South: Photographs by Steve McCurry

Acknowledgments

Read More from Paul Theroux

About the Author

Footnotes

Copyright © 2015 by Paul Theroux

Photographs copyright © Steve McCurry

All rights reserved

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to Permissions, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company, 215 Park Avenue South, New York, New York 10003.

www.hmhco.com

The Library of Congress has cataloged the print edition as follows:

Theroux, Paul.

Deep South : four seasons on back roads / Paul Theroux.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-544-32352-0 (hardcover : alkaline paper)—ISBN 978-0-544-32353-7 (ebook) 1. Southern States—Description and travel. 2. Southern States—Social life and customs. 3. Southern States—Social conditions. 4. Southern States—Biography. 5. Theroux, Paul—Travel—Southern States. 6. Scenic byways—Southern States. 7. Seasons—Southern States. I. Title.

F216.2.T45 2015

975—dc23

2015006631

Portions of this book appeared in Smithsonian magazine.

Some names in the text have been changed in the interest of privacy.

Excerpt from “The Arkansas Testament” from The Poetry of Derek Walcott, 1948–2013, by Derek Walcott, selected by Glyn Maxwell. Copyright © 2014 by Derek Walcott. Reprinted by permission of Farrar, Straus and Giroux, LLC.

Cover design by Mark R. Robinson

Cover photograph copyright © Steve McCurry

v1.1015

To the memory of George Davis (1941–2013) of Medford, Massachusetts—athlete, traveler, teacher, civil rights stalwart, unsung hero of Selma’s Bloody Sunday—in gratitude for fifty years of friendship

“We felt like we were alone and couldn’t make a difference. But what happened with the movement? People grouped together. It was a beautiful thing.”

On the red clay roads of the African bush among poor and overlooked people, I often thought of the poor in

America, living in just the same way, precariously, on the red roads of the Deep South, on low farms, poor pelting villages, sheepcotes, and mills—people I knew only from books, as I’d first known Africans—and I felt beckoned home.

—The Last Train to Zona Verde: My Ultimate African Safari (2013)

In this preposterous, unclassifiable book of my Travels, the thread of the stories and observations does not so much break as become intertwined, and in such a manner that, I am fully aware, much patience is needed to unravel and trace it in such an untangled skein.

—ALMEIDA GARRETT (JOÃO BAPTISTA DA SILVA LEITÃO), Travels in My Homeland (Viagens na Minha Terra, 1846)

PART ONE

* * *

Fall: “You Gotta Be Going There to Get There”

The stranger filleth the eye.

—Arab proverb, quoted by Richard Burton, First Footsteps in East Africa (1856)

Be Blessed: “Ain’t No Strangers Here”

In Tuscaloosa, Alabama, on a hot Sunday morning in early October, I sat in my car in the parking lot of a motel studying a map, trying to locate a certain church. I was not looking for more religion or to be voyeuristically stimulated by travel. I was hoping for music and uplift, sacred steel and celebration, and maybe a friend.

I slapped the map with the back of my hand. I must have looked befuddled.

“You lost, baby?”

I had driven from my home in New England, a three-day road trip to another world, the warm green states of the Deep South I had longed to visit, where “the past is never dead,” so the man famously said. “It’s not even past.” Later that month, a black barber snipping my hair in Greensboro, speaking of its racial turmoil today, laughed and said to me, in a sort of paraphrase of that writer whom he’d not heard of and never read, “History is alive and well here.”

A church in the South is the beating heart of the community, the social center, the anchor of faith, the beacon of light, the arena of music, the gathering place, offering hope, counsel, welfare, warmth, fellowship, melody, harmony, and snacks. In some churches, snake handling, foot washing, and glossolalia too, the babbling in tongues like someone spitting and gargling in a shower stall under jets of water.

Poverty is well dressed in churches, and everyone is approachable. As a powerful and revealing cultural event, a Southern church service is on a par with a college football game or a gun show, and there are many of them. People say, “There’s a church on every corner.” That is also why, when a church is bombed—and this was the fiftieth anniversary of the bombing of the sixteenth Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, where four little girls were murdered—the heart is torn out of a congregation, and a community plunges into pure anguish.

“You lost?”

Her voice had been so soft I had not realized she’d been talking to me. It was the woman in the car beside me, a sun-faded sedan with a crushed and cracked rear bumper. She was sipping coffee from a carryout paper cup, her car door swung open for the breeze. She was in her late forties, perhaps, with blue-gray eyes, and in contrast to the poor car she was dressed beautifully in black silk with lacy sleeves, a big flower pinned to her shoulder, wearing a white hat with a veil that she lifted with the back of her hand when she raised the coffee cup to her pretty lips, leaving a puckered kiss-daub of purple lipstick on the rim.

I said I was a stranger here.

“Ain’t no strangers here, baby,” she said, and gave me a merry smile. The South, I was to find, was one of the few places I’d been in the world where I could use the word “merry” without sarcasm. “I’m Lucille.”

I told her my name and where I wanted to go, the Cornerstone Full Gospel Baptist Church, on Brooksdale Drive.

She was quick to say that it was not her church, but that she knew the one. She said the name of the pastor, Bishop Earnest Palmer, began to give me directions, and then said, “Tell you what.”

One hand tipping her veil, she stared intently at the rim of her cup. She paused and drank the last of her coffee while I waited for another word.

“Shoot, it’s easier for me to take you there,” she said, then used the tip of her tongue to work a fleck of foam from her upper lip. “I don’t have to meet my daughter for another hour. Just follow me, Mr. Paul.”

I dogged the crushed rear bumper of her small car for about three miles, making unexpected turns, into and out of subdivisions of small bungalows that had been so hollowed out by a devastating tornado the previous year, they could accurately be described as fistulated and tortured. In the midst of this scoured landscape, on a suburban street, I saw the church steeple, and Lucille slowed down and pointed, and waved me on.

As I passed her to enter the parking lot, I thanked her, and she gave me a wonderful smile, and just before she drove on she said, “Be blessed.”

That seemed to be the theme in the Deep South: kindness, generosity, a welcome. I had found it often in my traveling life in the wider world, but I found so much more of it here that I kept going, because the good will was like an embrace. Yes, there is a haunted substratum of darkness in Southern life, and though it pulses through many interactions, it takes a long while to perceive it, and even longer to understand.

I sometimes had long days, but encounters like the one with Lucille always lifted my spirits and sent me deeper into the South, to out-of-the-way churches like the Cornerstone Full Gospel, and to places so obscure, such flyspecks on the map, they were described in the rural way as “you gotta be going there to get there.”

After circulating awhile in the Deep South I grew fond of the greetings, the hello of the passerby on the sidewalk, and the casual endearments, being called baby, honey, babe, buddy, dear, boss, and often, sir. I liked “What’s going on, bubba?” and “How y’all doin’?” The good cheer and greetings in the post office or the store. It was the reflex of some blacks to call me “Mr. Paul” after I introduced myself with my full name (“a habit from slavery” was one explanation). This was utterly unlike the North, or anywhere in the world I’d traveled. “Raging politeness,” this extreme friendliness is sometimes termed, but even if that is true, it is better than the cold stare or the averted eyes or the calculated snub I was used to in New England.

“One’s supreme relation,” Henry James once remarked about traveling in America, “was one’s relation to one’s country.” With this in mind, after having seen the rest of the world, I had planned to take one long trip through the South in the autumn, before the presidential election of 2012, and write about it. But when that trip was over I wanted to go back, and I did so, leisurely in the winter, renewing acquaintances. That was not enough. I returned in the spring, and again in the summer, and by then I knew that the South had me, sometimes in a comforting embrace, occasionally in its frenzied and unrelenting grip.

Wendell Turley

A week or more before I’d met Lucille, past ten o’clock on a dark night, I had pulled up outside a minimart and gas station near the town of Gadsden in northeastern Alabama.

“Kin Ah he’p you,” a man said from the window of his pickup truck. He had that tipsy querying Deep South manner of speaking that was so ponderous, fuddled beyond reason, I half expected him to plop forward drunk after he’d asked the question. But he was being friendly. Stepping out of his darkened, oddly painted pickup and gaining his footing, he swallowed a little, his lower lip drooping and damp. He finished his sentence, “In inny way?”

I said I was looking for a place to stay.

He held a can of beer but it was unopened. He had oyster eyes and was jowly and, though sober, looked unsteady. He ignored my appeal. I was thinking how now and then the gods of travel seem to deliver you into the hands of an apparently oversimple stereotype, which means you have to look very closely to make sure this is not the case—the comic, drawling Southerner, loving talk for its own sake.

“Ah mo explain something to you,” he said.

“Yes?”

“Ah mo explain the South to you.”

In my life as a traveler this was a first. From a great blurring distance, people sometimes say, “This is how things are in Africa,” or “China’s on the move,” and similar generalizations, but close-up never something so ambitious as, “I’m going to explain this entire region to you,” promising particulars.

“I’m just passing through. Never been here before. I’m a Yankee, heh-heh.”

“Ah knew that from your way of talking,” he said, “and from the plates on your vehicle.”

I told him my name and he extended his free hand.

“Ahm Wendell Turley. Ah have a business here in Gadsden. This vehicle is mah beater. Ah done that mahself.”

He was referring to the body of his old olive-colored pickup truck, stenciled all over with brown and green maple leaves.

“Camo,” he said. “This here I use for hunting deer.”

“Many deer around here?”

“Minny.”

And now I noticed that the pocket of his shirt was embroidered Roll Tide Roll, the slogan of the University of Alabama football team, passionately supported by Alabamians, some of whom I’d seen with the scarlet letter A tattooed on their neck, in homage. This seemed a way of reclaiming the true meaning of the word “fan,” which is short for “fanatic.”

“What were you going to explain to me about the South, Wendell?”

“Ah mo tell you.”

To a traveler, a stranger in this landscape, and especially one who is hoping to write about the trip, a man like Wendell is welcome and well met—patient, friendly, expansive, hospitable, and humorous in his manner. The man was a goober and a gift, especially late at night on a back road.

“What the hail . . .”

Before he could say more, a low-slung and rusted Chevrolet drew up beside us, loud hip-hop blaring from the open windows, and I caught the line “Have these niggas just waiting for a favor . . .”

A man in a greasy hat with its visor turned sideways swung his legs out and stood, leaving the engine running and the door open, so the music was amplified by the gaping doorway. Coarse tufts of stuffing were visible in the burst-open upholstery of the driver’s seat.