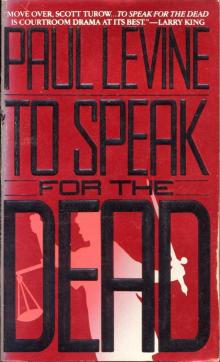

To speak for the dead

Paul Levine

To speak for the dead

Paul Levine

Paul Levine

To speak for the dead

:

"The Coroner shall view the bodye and the woundes and the strokes, and the bodye shalbe buryed. And yf the Coroner fynde the bodye buried before his comminge, he shall not omitte to digge up the bodye.

"And when the inquest is sworne ye Coroner must inquire if ye person were slayne by felony or by misadventure. And after it shalbe enquired who were presente at the dede, and who be coulpable of the ayde, force, commandement, consent, or receite of suche felonies wittingly."

Anthony Fitzherbert,

The New Book of Justice, 1545 a.d.

TO SPEAK FOR THE DEAD

MAY 1980

Prologue

TABLE DANCER

He would remember the sounds-the wailing sirens, the moans of the injured-and the smells, a smoky ashen stench that clung to hair and clothing. Late the first night, he slipped into the parking lot for some air, and he tasted the sky as the smoke rose above Miami's inner core. He heard the city scream, the popping of wood and plastic aflame, short bursts of gunfire followed by silence, then the crackle of police radios. Later he would remember slipping in a puddle of blood on the tile floor of the Emergency Room.

He would not leave the hospital for seventy-two hours, and by then, he had treated more gunshot wounds than most doctors see in a lifetime. Blacks against police, whites against blacks, savage violence in a ghetto hopelessly misnamed Liberty City. By the time the shooting stopped and the fires were out, an eerie silence hung over the area, an inner-city battle zone where neither side surrendered, but each put away its weapons and withdrew.

"That's a real poster ass, huh?"

Roger Salisbury shot a sideways glance at the man next to him. A working guy, heavy boots and a plaid shirt open at the neck. Thick hands, one on a pack of cigarettes, the other on his drink, elbows resting on the scarred bar. "Like to frame that ass, hang it in the den next to Bob Griese."

"Uh-huh," Salisbury mumbled. He didn't come here to talk, didn't know why he came. Maybe to lose himself in a place crammed with people and noise, to be alone amid clinking glasses, laughter, and the creaminess of women's bodies. He strained his neck to see her above him on the stage.

"Not that one," the man said, tapping the bar with a solid index finger. "Over there at the stairs, the on-deck circle. A real poster ass. Never saw a skinny girl with an ass like that. Eat my lunch offa that."

She wore a black G-string, a red bikini top, and red high-heeled shoes. If not for the outfit and the setting, she could have been a cheerleader with a mom, dad, and grandmom in Kansas. Good bone structure, fair complexion with freckles across a button nose, short wavy reddish-brown hair, wholesome as a wheat field. The face belonged in a high school yearbook; the body launched a thousand fantasies. Her thin waist accentuated a round bottom that arched skyward out of both sides of the tiny G-string. Her breasts were round and full. She was warming up, fastening a prefab smile into place, taking a few practice swings, tapping a sequined shoe in time to Billy Joel, who was turned up way too high:

What's the mat-ter with the clothes I'm wear-ing?

Can't you tell that your tie's too wide?

May-be I should buy some old tab col-lars.

Wel-come back to the age of jive.

The working guy was looking at Salisbury now, sizing him up. Looking at a blow-dry haircut that was a little too precise for a place like this. Clean shaven, skin still glistening like he'd just spanked his face with Aqua Velva at two a.m., as if the girls in a beat-your-meat joint really care. The hair was starting to show some early gray, the features pleasant, if not matinee idol stuff. A professor at Miami-Dade maybe, the working guy figured.

Salisbury knew the guy was looking at him, now at his hands, just as he had done. Funny how hands can tell you so much. Proud of his hands. Broad and strong. They could have swung a pick, except there were no calluses. He had washed off the blood, scrubbing as hard after surgery as he had before the endless night began. Seventy-two hours with only catnaps and stale sandwiches until the hospital cafeteria ran out. But he stood there the whole time, one of the leaders, the chief orthopedics resident, setting broken bones, picking glass and bullet fragments out of wounds, calming hysterical relatives.

After showering at the hospital, he had tossed the soiled lab coat into the trash and grabbed a blue blazer from his locker. Now he was nursing a beer and trying to forget the carnage. He could have gone home. Twenty-seventh Avenue was finally open after the three-day blockade. But too tired to sleep, he wound through unfamiliar streets and was finally lured out of the night by the neon sign of the Tangiers on West Dixie. He would think about it later, many times, why he stopped that night, what drew him to such a strange and threatening place. Pickup trucks and old Chevys jammed the parking lot. Music blared from outdoor loudspeakers, a rhythmic, pulsating beat intended to tempt men inside just as the singing of the Sirens drew Greek sailors onto the rocks. It might have been the flashing sign. The throbbing colors got right to the point-NUDE GIRLS 24 HOURS

… NUDE GIRLS 24 HOURS-blinking on, blinking off, proof of bare flesh moment after moment after moment.

The working guy was talking to him: "I say let 'em burn colored town down to the ground if they want to, no skin offa my nose. I mean, the cops was wrong, killing one of the coloreds, had his hands cuffed behind his back, no need for that. But some of 'em just looking for excuses to behave like animals. They burned a poor Cuban alive in his car, heard it on the radio."

"We tried to save him," Salisbury said quietly.

The guy gave him a look. "Sure! You're a doctor. Should have known. Jesus, you musta seen it all. Wait a minute, Sweet Jesus, here comes Miss Poster Ass. She's worth a twenty-dollar dance, or I'm the Prince of Wales."

Roger Salisbury watched her walk toward them, an inviting smile aimed his way. The other men around the small stage hooted and slapped their thighs. Roger Salisbury lowered his eyes and studied his drink.

"Your first time?" the man asked. Silence. "Yeah, your first time. Loosen up. Here's the poop. First the girls dance out here on the bar stage. No big deal, they take it all off, you stick a dollar bill in their garter and maybe one'll kiss you. In the back, where it's darker, you got your table dances, twenty bucks. That's one-on-one and I may buy me an up-close-and-personal visit with Miss Poster Ass. Haven't been able to get here all week what with the jungle bunnies staging their block parties."

On stage now, grinding to the music, no longer the Kansas cheerleader. Ev-ry-bod-y's talk-in' 'bout the new sound. Funny, but it's still rock and roll to me. In a few moments, the bikini top was off, firm breasts bounding free. The G-string came next, and then she arched her back, bent over, and propped her hands on her knees looking away from the men. The poster ass wiggled clockwise as if on coasters, then stopped and wiggled counterclockwise. Salisbury stared as if hypnotized. The ass quivered once, fluttered twice with contractions that Roger Salisbury felt deep in his own loins, then stopped six inches from his face. His fatigue gone, the swirl of blood and bodies a dreamy fog, Roger Salisbury fantasized that the perfect ass wiggled only for him. He didn't see the other men, some laughing, some bantering, others conjuring up their own steamy visions. None of the others, though, seemed spellbound by an act as old as the species.

The dance done, the girl smiled at Roger Salisbury, an open interested smile, he thought. And though she smiled at each man, again he thought it was only for him. She sashayed from one end of the small stage to the other, collecting dollar bills in a black garter while propping a red, high-heeled shoe on the rim between the stage and the bar. Other than the garter and the shoes, she was naked, but her fac

e showed neither shame nor seduction. She could have been passing the collection plate at the First Lutheran Church of Topeka. Roger Salisbury slipped a five-dollar bill into her garter, removing it from his wallet with two fingers, never taking his eyes off the girl. A neat trick, but he could also tie knots in thread with a thumb and one finger inside a matchbox. Great hands. The strong, steady hands of a surgeon.

Her smile widened as she leaned close to him, her voice a moist whisper on his ear. "I'd like to dance for you. Just you." And he believed it.

Roger Salisbury believed everything she said that night. That she was a model down on her luck, that her name was Autumn Rain, that all she wanted was a good man and a family. They talked in the smoky shadows of a corner table and she danced for him alone. Twenty dollars and another twenty as a tip. He didn't lay a hand on her. At nearby tables men grasped tumbling breasts, and the girls stepped gingerly from their perches in four-inch spikes to sit on customers' laps, writhing on top of them, grinding down with bare asses onto the fully clothed groins of middle-aged men. "Didja come?" the heavy girl at the next table whispered to her customer, already reaching for a tip.

"I've never seen anything like this," Roger Salisbury said, shaking his head. "It's half prostitution and half masturbation." He gestured toward the overweight girl who was gathering her meager outfit and sneaking a peek at the president's face on the bill she had glommed from a guy in faded jeans. "You don't do that, do you?" Salisbury asked.

She smiled. Of course not, the look said.

He asked her out.

Against the rules, she said. Some guys, they think if you're an exotic dancer, it means for fifty bucks you give head or whatever.

But I'm different, Roger Salisbury said.

She cocked her head to one side and studied him. They all thought they were different, but she knew there were only two kinds of men, jerks and jerk-offs. Oh, some made more money and didn't get their fingernails dirty. She'd seen them, white shirts and yellow ties, slumming it, yukking it up. But either way, grease monkeys or stockbrokers, once those gates opened and the blood rushed in, turning their worms into stick shifts, they were either jerks or jerk-offs. The jerk-offs were mostly young, wise guys without a pot to piss in, spending all their bread on wheels and women, figuring everything in a skirt-or G-string-was a pushover. Jerks were saps, always falling in love and wanting to change you, make an honest woman out of you. Okay, put me in chains, if the price is right. This guy, jerk all the way.

I'm a doctor, he said.

Oh, she said, sounding impressed.

He told her how he had patched and mended those caught in the city's crossfire, how he wanted to help people and be a great doctor. She listened with wide eyes and nodded as if she knew what he felt deep inside and she smiled with practiced sincerity. A doctor, she figured, made lots of money, not realizing that a resident took home far less than an exotic dancer and got his hands just as dirty.

She looked directly into Roger Salisbury's eyes and softened her own. He looked into her eyes and thought he saw warmth and beauty of spirit.

Roger Salisbury, it turned out, was better at reading X rays than the looks in women's eyes.

DECEMBER 1988

1

THE RONGEUR

When the witness hesitated, I drummed my pen impatiently against my legal pad. Made a show of it. Not that I was in a hurry. I had all day, all week. The Doctors' Medical Insurance Trust pays by the hour and not minimum wage. Take your sweet time. The drum roll was only for eifect, to remind the jury that the witness didn't seem too sure of himself. And to make him squirm a bit, to rattle him.

First the pen clop-clop-clopping against the legal pad. Then the slow, purposeful walk toward the witness stand, let him feel me there as he fans through his papers looking for a lost report. Then the stare, the high-voltage Jake Lassitei laser beam stare. Melt him down.

I unbuttoned my dark suitcoat and hooked a thuml into my belt. Then I stood there, 220 pounds of ex-football player, ex-public defender, ex-a-lot-of-things, leaning against the faded walnut rail of the witness stand, home to a million sweaty palms.

Only forty seconds since the question was asked, but I wanted it to seem like hours. Make the jury soak up the silence. The only sounds were the whine of the air condition ing and the paper shuffling of the witness. Young lawyers sometimes make the mistake of filling that black hole, o clarifying the question or rephrasing it, inadvertently breathing life into the dead air that hangs like a shroud over a hostile witness. What folly. The witness is zipped up because he's worried. He's thinking, not about his answer, but of the reason for the question, trying to outthink you, trying to anticipate the next question. Let him stew in his own juice.

Another twenty seconds of silence. One juror yawned. Another sighed.

Judge Raymond Leonard looked up from the Daily Racing Form, a startled expression as if he just discovered he was lost. I nodded silently, assuring him there was no objection awaiting the wisdom that got him through night classes at Stetson Law School. The judge was a large man in his fifties, bald and moon-faced and partial to maroon robes instead of traditional black. History would never link him with Justices Marshall or Cardozo, but he was honest and let lawyers try their cases with little interference from the bench.

Earlier, at a sidebar conference, the judge suggested we recess at two-thirty each day. He could study the written motions in the afternoon, he said with a straight face, practically dusting off his binoculars for the last three races at Hialeah. A note on the bench said, "Hot Enough, Rivera up, 5-1, ninth race." In truth, the judge was better at handicapping the horses than recognizing hearsay.

Another thirty seconds. Then a cleared throat, the sound of a train rumbling through a tunnel, and the white-haired witness spoke. "That depends," Dr. Harvey Watkins said with a gravity usually reserved for State of the Union messages.

The jurors turned toward me, expectant looks. I widened my eyes, all but shouting, "Bullshit." Then I worked up a small spider-to-the-fly smile and tried to figure out what the hell to ask next. What I wanted to say was, Three hundred bucks an hour, and the best you can do is "that depends. " One man is dead, my client is charged with malpractice, and you're giving us the old softshoe, "that depends."

What I said was, "Let's try it this way." An exasperated tone, like a teacher trying to explain algebra to a chimpanzee. "When a surgeon is performing a laminectomy on the L3-L4 vertebrae, can he see what he's doing with the rongeur, or does he go by feel?"

"As I said before, that depends," Dr. Watkins said with excessive dignity. Like most hired guns, he could make a belch sound like a sonnet. White hair swept back, late sixties, retired chief of orthopedics at Orlando Presbyterian, he had been a good bone carpenter in his own right until he lost his nerves to an ice-filled river of Stolichnaya. Lately he talked for pay on the traveling malpractice circuit. Consultants, they call themselves. Whores, other doctors peg them. When I defended criminal cases, I thought my clients could win any lying contest at the county fair. Now I figure doctors run a dead heat with forgers and confidence men.

No use fighting it. Just suck it up and ask, "Depends on what?" Waiting for the worst now, asking an open-ended question on cross-examination.

"Depends on what point you're talking about. Before you enter the disc space, you can see quite clearly. Then, once you lower the rongeur into it to remove the nucleus pulposus, the view changes. The disc space is very small, so of course, the rongeur is blocking your view."

"Of course," I said impatiently, as if I'd been waiting for that answer since Ponce de Leon landed on the coast. "So at that point you're working blind?"

I wanted a yes. He knew that I wanted a yes. He'd rather face a hip replacement with a case of the shakes than give me a yes.

"I don't know if I'd characterize it exactly that way…"

"But the surgeon can't see what he's doing at that point, can he?" Booming now, trying to force a good old-fashioned one-word answer. Come on, Dr.

Harvey Wallbanger, the sooner you get off the stand, the sooner you'll be in the air-conditioned shadows of Sally Russell's Lounge across the street, cool clear liquid sliding down the throat to cleanse your godforsaken soul.

"You're talking about a space maybe half a centimeter," the doctor responded, letting his basso profundo fill the courtroom, not backing down a bit. "Of course you don't have a clear view, but you keep your eye on the rongeur, to be aware of how far you insert it into the space. You feel for resistance at the back of the space and, of course, go no farther."

"My point exactly, doctor. You're watching the rongeur, you're feeling inside the disc space for resistance. You're operating blind, aren't you? You and Dr. Salisbury and every orthopedic surgeon who's ever removed a disc…"

"Objection! Argumentative and repetitious." Dan Cefalo, the plaintiff's lawyer, was on his feet now, hitching up his pants even as his shirttail flopped out. He fastened his third suitcoat button into the second hole. "Judge, Mr. Lassiter is making speeches again."

Judge Leonard looked up again, unhappy to have his handicapping interrupted. Three to one he didn't hear the objection, but a virtual lock that it would be sustained. The last objection was overruled, and Judge Leonard believed in the basic fairness of splitting the baby down the middle. It was easier to keep track if you just alternated your rulings, like a kid guessing on a true-false exam.

"Sustained," the judge said, nodding toward me and cocking his head with curiosity when he looked at Cefalo, now thoroughly misbuttoned and hunched over the plaintiff's table, a Quasimodo in plaid polyester. Then the judge handed a note to the court clerk, a young woman who sat poker-faced through tales of multiple homicides, scandalous divorces, and train wrecks. The clerk slipped the note to the bailiff, who left through the rear door that led to the judge's chambers. There, enveloped in the musty smell of old law books never read much less understood, he would give the note to the judge's secretary, who would call Blinky Blitstein and lay fifty across the board on Hot Enough.