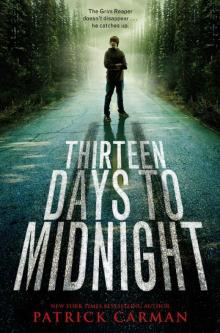

Thirteen Days to Midnight

Patrick Carman

Copyright

Copyright © 2010 by Patrick Carman

All rights reserved. Except as permitted under the U.S. Copyright Act of 1976, no part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, or stored in a database or retrieval system, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

Little, Brown and Company

Hachette Book Group

237 Park Avenue, New York, NY 10017

Visit our website at www.HachetteBookGroup.com

www.lb-teens.com

Little, Brown and Company is a division of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

The Little, Brown name and logo are trademarks of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

First eBook Edition: April 2010

The characters and events portrayed in this book are fictitious. Any similarity to real persons, living or dead, is coincidental and not intended by the author.

ISBN: 978-0-316-08880-0

Contents

COPYRIGHT

MIDNIGHT

ONE DAY LATER

THIRTEEN DAYS TO MIDNIGHT

8:12 AM MONDAY, OCTOBER 8TH

FIFTEEN YEARS IN FIVE MINUTES FLAT

TWELVE DAYS TO MIDNIGHT

3:00 PM TUESDAY, OCTOBER 9TH

ELEVEN DAYS TO MIDNIGHT

WEDNESDAY, OCTOBER 10TH

TEN DAYS TO MIDNIGHT

THURSDAY, OCTOBER 11TH

NINE DAYS TO MIDNIGHT

FRIDAY, OCTOBER 12TH

EIGHT DAYS TO MIDNIGHT

9:00 AM SATURDAY, OCTOBER 13TH

SEVEN… SIX… FIVE… FOUR DAYS TO MIDNIGHT

8:20 AM MONDAY, OCTOBER 15TH

NOON, THURSDAY, OCTOBER 18TH

THREE DAYS TO MIDNIGHT

8:20 AM FRIDAY, OCTOBER 19TH

FOURTEEN HOURS TO MIDNIGHT

SATURDAY, OCTOBER 20TH

SEVEN HOURS TO MIDNIGHT

5:05 PM

MIDNIGHT

ONE WEEK LATER

For Peter Rubie,

friend and mentor

a cognizant original v5 release october 09 2010

MIDNIGHT

Jacob Fielding stood in a small room and stared at a body. It was a dead body, someone he could have saved but chose not to. Jacob had let the person die because, in his view, it was the right thing to do.

He watched in silence, felt the air in his lungs catch and flutter as he tried to stay calm. What was he going to do now? How could he explain? People wouldn’t understand. They’d say he was a killer.

The body hadn’t moved in the seven minutes Jacob Fielding stared at it, but it had made some unpleasant sounds that would lodge in his memory and prove difficult to get rid of.

“All of us play the same tune sooner or later,” Jacob’s best friend said. “The black symphony of the dead.”

Milo Coffin with the dyed hair and the dark humor. He of all people would know.

Jacob took out Mr. Fielding’s Zippo lighter and flicked it open, searching for a distraction. He heard the clank of metal and the sandpaper jingle of fire coming to life.

He held the flame under his fingers and wished it would burn, but it didn’t.

Jacob Fielding had come to believe that death was his closest friend. It was there when he stood in front of the mirror in the morning, there when he wrote and talked and slept. Death was always watching, trying to decide if the time had come to step into the spotlight.

Jacob Fielding was an expert in his field, and death was his subject.

It was the enemy he had come to love.

ONE DAY LATER

If you could have only one superpower, what would it be?

People get that question all the time, but hardly anyone I’ve asked has a logical answer. I’m surprised by how often people answer flying, because when you really stop to think about it, flying is dangerous as hell. Just figuring out how to do it right would more than likely involve slamming into a building, so you’d probably be dead or badly injured in the first ten minutes. Best-case scenario you’d get some other power to go along with it—like turning into liquid if you hit a slab of pavement doing ninety.

But then, adding something else into the mix is more than the question allows for.

If you could have only one superpower, what would it be?

Invisibility has a lot going for it. It’s not the sort of superpower that would automatically get you hurt and seriously, there are some sweet ways you could put that kind of talent to good use: girls’ locker room, gathering dirt on overbearing teachers, tripping people… But you’re not getting invisible clothes to go with your invisibility. Getting used to walking around in the buff 24-7 would be damn hard to do. I’d die of stress just thinking about having my skills fail me while trying to escape from KFC with a bucket of chicken.

And this brings up another huge problem. Temptation.

Say you get lucky and somehow the invisibility power comes with a set of invisible clothes. You’d be on the dark side before you could curl your toes and count to ten. Nobody I hang out with could walk into a Kmart totally invisible and leave without stealing video games, DVDs, and cans of Red Bull up the wazoo. If you can hide it under your invisible jacket, you’re taking it. And that’s not a superpower, that’s a lose-your-soul-to-the-devil power. I should know—I go to a Catholic school and I’m telling you: invisibility = eternal damnation. You can take it to the bank.

Reading minds? That one blows from the word go. Listening to the crap going through the minds of all the idiots at my school all day? No, thanks.

Throwing balls of fire, time travel, nunchuck skills… blah, blah, blah. I’ve worked my way through every superpower there is and found them all wanting for one reason or another. The truth is that every power, no matter how amazing, is loaded with trouble of the worst kind.

It would have been nice if someone had let me in on the joke thirteen days ago. Things could have been a lot easier for me.

This is how it went down, or at least how I remember it. I don’t have a superhuman memory, but I can tell you this much for sure:

I killed a guy, maybe two. Possibly three.

I have one power. Not two or three or four. Just one.

I met a girl, and she changed everything.

THIRTEEN

DAYS TO

MIDNIGHT

8:12 AM

MONDAY, OCTOBER 8TH

I arrived in the parking lot full of cars after the morning bell on purpose, just in case I changed my mind and wanted to cut school after all. It felt like all the blood had been drained out of the world while I was away.

The sky was overcast and heavy. Around here, clouds can take in water for weeks on end, then drizzle for twenty-five or thirty days in a row, slowly delivering back what they’ve stolen. Looking up, I had the feeling we were in for a long month of misty rain.

Ten out of ten cars in the Holy Cross parking lot were crap for a simple reason: Holy Cross was a dying school. Enrollment had been in a freefall for years, and they’d dwindled to 137 souls in four grades by the time I got there as a gangly, foul-mouthed sophomore. I’ve since cleaned up my language—mainly because it bothered Mr. Fielding so much—but I still remember the gorgeous sound of a well-placed F-word rolling off my tongue.

Two years ago they finished building South Ridge High, a brand new 1,300-student public high school with state-of-the-art everything. Its high-tech and pristine athletic facilities are housed a mere mile down the road. When that place fired up its lights for the first time, most of the best athletes, brainiacs, and teachers took off. What was left were kids with parents who’d gone to Holy Cross before them in the eighties, back when three hundred kids packed the halls between classes

.

Just so we’re clear from the beginning, me and my friends hate South Ridge High, especially the defectors who used to be Holy Crossers. We’re a wad of chewing gum on the heel of mighty South Ridge, and they never let us forget it.

As I stared at the clunkers in the parking lot and felt the oppressively low clouds closing in, school was the last place I felt like spending the day, especially given all that had happened. I was just about to turn around and head for the 7-Eleven when I was spotted by Miss Pines, a mostly pretty, often tired-looking fiction writer who taught second period English and was eternally late for every class.

“Jacob Fielding, nice to have you back,” said Miss Pines, flipping shut her cell phone as she kicked her car door shut. Miss Pines, the only black teacher at our school, almost always wore yellow, and today was no exception.

“I was so sorry to hear about Mr. Fielding,” she continued. She was one of the strictest teachers at Holy Cross, but she could be nice when the situation called for it. Miss Pines looked at me sort of sideways, a habit she had that always preceded a question. “How you holding up?”

“Better than this place,” I said, only half joking. “How about you?”

“I’m fine. Late as usual, but fine. I got that trait from my mom. She was tardy for everything—church, work, dinner on the table. You know I didn’t show up on time for school but three times my whole freshman year? I blame her for all my problems.”

“Good thing I don’t have that difficulty,” I said. “The mom thing, I mean.”

“Maybe so,” said Miss Pines, nodding thoughtfully as if she really might think this was true. She tilted her head again. “Still expecting Father Tim back tomorrow night?”

“As far as I know.”

Holy Cross was in need of cash and it was Father Tim’s job to get it, which meant driving from Salem to Seattle to meet with the bishop. In a small school it’s tough to keep that sort of thing secret, especially when one of the students (that’d be me) is living in the church house now.

“How’s the novel?” I asked. As far as I knew, Miss Pines had been working on the same manuscript for about ten years.

“Same as when you asked me last time. Not finished.”

Miss Pines moved on, yelling over her shoulder that she was really late, which meant I was late, which meant I’d better get moving.

I lingered in the parking lot a little longer, staring at the countless weeds poking through cracked concrete, thinking about what had kept me away from school for a whole week. Mr. Fielding, my foster parent, was dead. There was no Mrs. Fielding, which complicated matters. And then there was the fact that I loved the guy, and the additional detail about how we were together when it happened—only he died, and I didn’t.

I heard two quick taps on a horn, which shook me out of my misery, and knew without looking that Milo was coming up the long driveway in his egg-white Geo Metro. He pulled into an empty spot in front of me and lurched to a stop, got out, slammed the door, and, leaning hard on the rim of the windshield, folded his arms across his chest. He looked me up and down like I was a prowler from South Ridge about to layer the school in graffiti.

“You’re not seriously going in there looking like that?”

Glancing down at my school uniform, I saw he had a point. It was pressed to wrinkle-free perfection. Milo slacked on the school dress code wherever legally possible. He’d tried black eyeliner, army boots with missing laces, and a string of ill-advised piercings (ears, nose, eyebrow). In every case, he’d been sent home by Father Tim with the same message: “Not in my school.”

“Nice to see you, too, Milo. Glad you missed me.”

I dropped my heavy backpack on the wet pavement and began rolling up the white sleeves of my shirt.

“A’right, look—I’ll cut you some slack because, you know, because of everything that’s going on. But I’m not the one who went dark for a week. That’d be you.” Milo picked at the silver duct tape holding the windshield of his car in place. Rust was winning an all-out assault on both front doors, the trunk was held down with a twisted bungee chord, and both bumpers had fallen off. “And don’t tell me you dropped your cell phone in the john again. I’m not buying it. What have you been doing with yourself?”

I loosened my tie a few notches and picked up my bag. There were no lockers at Holy Cross, so the bag was stupidly heavy, loaded down with books and homework I’d not been able to touch for days.

“Well? Are you gonna answer me or do I have to beat it out of you?” asked Milo.

“Go ahead, hit a guy while he’s down.” I had the excuse of a lifetime for going dark, but I still felt bad for flaming out on my closest friend at Holy Cross.

He’d dug up the corner of the tape and began pulling it with his fingers. “You’re beating yourself up pretty good without my help,” he mumbled.

I’m quite a bit taller than Milo, but I’m also rail-thin. Milo, on the other hand, is short and solid, a ferocious wrestler. He’d have no problem kicking the crap out of me if he ever wanted to. But right now, he was just trying to pull me back into the land of the living. I got that.

“Sorry, okay? I just needed to be alone. I was on lock-down at the church house, getting my head straight. It actually felt pretty good, being off the grid for a week.”

“It’s cool.” Milo lifted his head as he kicked the gravelly parking lot. “I’m sure it ain’t easy. But you can’t just disappear like that. People ask about you. They expect me to know something.”

“Let ’em wonder. I don’t care anymore.”

“If you weren’t in such bad shape already I’d put the Holy Cross on your grieving head.” The “Holy Cross” was like a headlock, only you held the guy in reverse and rapped his forehead with your knuckles. Hell of a move if you could pull it off without getting bitten in the process.

“Don’t go easy on me. I’m fine.”

“Don’t tempt me.”

I smiled. Things were back to how they’d always been between us. I’d met Milo first, before anyone else at Holy Cross, at his parents’ bookstore. “You ready for this place again?” asked Milo, pushing the long strip of duct tape back in place with the heel of his hand.

“Probably not. But the church house is creepy quiet, especially with Father Tim out of town. He’s not coming back until tomorrow night and the old guys are downright depressing. Better here than watching dust collect on Bibles.”

A dull silence hung between us. How do you talk to your friend about death and loneliness—and guilt?

Milo’s phone vibrated, and he reached into his pocket, reading a text that had just arrived.

“Someone new showed up while you were gone,” he said, clicking out a message and returning his phone to his pocket.

“You’re kidding. Guy or girl?”

“Girl.”

“Promising. What’s she look like?”

“You’ll see.”

Milo pointed into the backseat of his car, and I leaned closer, spotting a red skullcap and a longboard.

“She left her stuff in your backseat?”

“You guessed it.”

“She must be a real dog.”

“Nope.”

I was damn near positive Milo was lying.

“Hang for the morning, and I promise you won’t be sorry,” said Milo, sensing I was thinking of ditching school for another day of solitary confinement. “I’ll introduce you to the new girl. She has something for you.”

“She doesn’t even know me.”

“She knows enough.”

Milo started for the entrance to Holy Cross and I weighed my options: enter the school and find a girl with a gift (odds are she’d be hideous if she existed at all), or I could return to the church house and watch retired priests play dominoes and talk about gardening.

I decided to follow Milo into the school.

We were already late for first period, so the halls were empty when Milo opened the door to Mr. D’s science class and left me standin

g in the gap. There’s nothing quite as unnerving as incoherent mumbling and the sound of phone keys texting the moment you walk into a room.

“Well, everyone knows you’re back now,” said Milo, moving off toward his own first period class. “At least that’s over with. Don’t cut out at lunch, I told Ophelia to meet us.”

“Ophelia?”

I stood in the doorway listening to the sound of thumbs on little keyboards.

“Text at your own peril,” shouted Mr. D, picking a wooden box up off his desk. It was widely known that if your phone ended up in Mr. D’s box he would hold it for a week and answer all your incoming messages with the same four words: shut your pie hole.

Not bad for an old guy.

Attending a small private school has a certain routine that must be endured. Everyone knows everyone else, and even if we’re in different groups or flat-out hate each other, there’s a persistent problem that hovers over the school: We’re all stuck with one another. I think this is one of the main reasons we lost so many to South Ridge. Over there a guy could pick a new friend every seven minutes and never run out. Not the case at Holy Cross.

And so I tolerated the sympathetic looks of Mr. D and all the guys in the class. I tolerated the half hugs and sweet smiles of Mary, June, Emily, Bethany, Marissa, Madison, and Taylor, who all approached me. And then, mercifully, it was over and Mr. D was telling everyone to settle down and turn to page 215.

I slid into my seat and looked around the room, making sure I hadn’t missed a new girl with the face of a cow and long, dark hairs growing out her nose. Whoever Ophelia was, if she was at all, she’d be in the other first period class with Miss Pines. All the faces in Mr. D’s class were ones I’d seen before.

Ethan poked me in the back with a pencil.

“Yo, man. Good to have you back. This place sucks without you. Tennis at lunch.” It wasn’t a question. That’s Ethan for you.