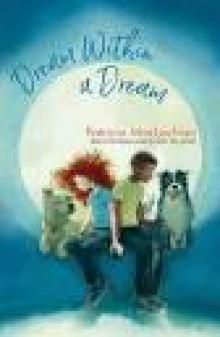

Dream Within a Dream

Patricia MacLachlan

For my children—and their children—with thanks to George Munemo, who thought I should write this book.

Is all that we see or seem

But a dream within a dream?

—EDGAR ALLAN POE

The only thing worse than being blind is

having sight but no vision.

—HELEN KELLER

Nakupenda

—SWAHILI WORD FOR “I LOVE YOU”

Prologue

My grandfather Jake’s Deer Island farm runs down to the sea—sweet grass slipping to water.

Sometimes seals sun on the warm sand.

There used to be a large flock of sheep in the field that the townspeople would help shear twice a year. Now there are only three sheep—Jake’s favorites: Bitty and Flossie and Flip.

Other things have changed.

My grandfather is losing his eyesight.

He can still take care of his three sheep.

He can still cook.

He can read when he uses a large viewing machine.

But soon—the worst thing of all—is that he may not be able to drive his beloved 1938 midnight-black Cord car with running boards.

He has proudly driven my grandmother to town for years when she doesn’t walk or bicycle to the store.

He has driven his colorfully decorated car in parades and on the Fourth of July.

He has washed and polished the car.

He has loved the car.

Things are changing.

I hate change.

1

Change

I’m telling my own story here.

I’m a secret writer. My teacher has never read my journal. My mother and father have not read it either. I think my brother, Theo, has read it, but he hasn’t said so. My life is like a dream within a dream, as Edgar Allan Poe writes.

For one thing my name is Louisiana. My parents were bird-watching through the South when my mother was very pregnant. What were they thinking?

So I was born in Louisiana.

My name is Louisiana. Louisa for short.

And I have a large mass of long curly red hair. Where did that come from?

My friends have smooth long hair that moves. My hair is long and wildly curly like an out-of-control Brillo pad. Look it up if you don’t know what that is. A so-called friend once said, “Too bad about your hair, Louisa.”

I am filled with anguish.

My younger brother, Theo, tells me most times boys don’t bother saying rude things about hair.

Theo is strangely understanding, yet direct.

“Tough to be you, Lou,” he says with sympathy when I complain to him.

“Theo is a linear thinker,” says Jake. “Put words to what you are feeling and you can solve it. Like me.”

Theo is only eight but could be seventy.

My grandmother Boots says the same thing in her own way.

“Theo is old,” she says.

My grandmother’s real name is Lily, but she is called Boots because she loves them. Everyone in her family has always worn boots, her grandmother and grandfather, her aunts and uncles and cousins everywhere. Even the babies wear boots. My favorite uncle, whose name I forget, is called Boots too. He’s a poet who fell in love with cows and is now a farmer.

My grandmother Boots prefers wellies. She has four pairs in the front closet: red, green, yellow, and black. They are tall and come up to her knees.

When Uncle Boots visited, it was confusing. We tried to change my grandmother’s name to Boo.

“No,” she said.

“What about Wellie?”

“Never.”

So now we have more than one Boots.

Boots knows most everything.

She knows, for instance, that her son—my father—and his wife—my mother—are “dense” about some things even though they’re “disturbingly” intelligent, as she puts it.

Boots is my hero.

Our parents have plunked Theo and me on the little island for the long summer, as they always do, while they go off to do their bird research. My father is an ornithologist, and my mother is a photographer. You haven’t seen anyone more excited than my father over the possible sighting of an ivory-billed woodpecker in some bug-ridden habitat. Or New Caledonian crows, who sometimes make and use tools to catch grubs. My mother often climbs trees to photograph a bird’s nest made of animal fur, human hair, sticks, small bones, and an every-once-in-a-while treasure such as a gold bead. Sometimes baby birds in a nest squawk at her when she surprises them.

Theo refers to our parents’ summers as “bird bedlam.”

My father, of course, wears boots.

Theo and I love coming to Deer Island for peace, reading books, taking long walks by the water, swimming, and mostly talking to Jake and Boots. Theo talks all year long about the island as if it is his dream.

“Boots?”

“Yes?”

“I heard something when my parents were talking.”

Boots nods. She is not shocked that I was eavesdropping. Nothing much shocks Boots.

“They were saying that you and Jake might move to our house when he can’t see well enough to drive.”

Boots laughs. Right out loud. “No. This is our home. The place we love. We can walk to almost everyplace we want to be.”

“Or, they said, maybe we could move here to help,” I say.

“Taking you out of school and all you know? Don’t worry, Louisa. They’re not invited.”

I nod, relieved. “I hate change,” I say.

“Well, sometimes change can be exciting. An adventure. Sometimes you find out who you are.”

“I don’t think so,” I say.

“I know so,” says Boots. “Trust me. I know everything.”

She puts her arms around me. “It’s hard being you,” she says.

“That’s what Theo said!” I say.

“Of course he did,” says Boots, making me laugh and cry at the same time.

Tess jumps up on us as we stand there in the kitchen.

So Boots puts on her yellow wellies, and we take Tess walking down the field, past the sheep. Tess practices her old habit of herding, nipping at their heels.

They stare and look away again, bored.

Seals are sleeping in the sun. Tess goes over, and they hiss at her. Tess prances and dances around them. She isn’t afraid.

The seals aren’t afraid either.

The waves are slow and calm.

“There will be a nice sunset tonight,” says Boots. “Change, Louisa. The sunset comes, then darkness comes and the moon rises, and then in the morning, the sun. Change comes, and sometimes you can’t do anything about it.”

“I can try,” I say.

“Then you will be unhappy,” says Boots.

Herring gulls fly over us, making their laughing sound.

“Jake’s not unhappy,” I say.

“Jake’s positive. He loves his life. ‘It is what it is,’ he says. ‘No problem,’ ” says Boots.

“What about if he can’t drive his car?” I ask.

Boots sighs and throws a stick down the beach for Tess.

“That may be a small problem for him,” she says flatly.

Tess runs back and drops the stick at Boots’s feet. Boots throws it again.

“But something will happen,” she says.

“What do you mean?”

“Something,” repeats Boots. “Remember the sunset, the moon, sunrise, the morning sun. Something always happens.”

The seals slip back into the sea. Tess watches them swim off in the water. They swim on their backs and look at her. Then they dip down and are gone.

Behind them the small morning ferry leaves the island to g

o to the mainland. I shade my eyes and look over to the blurry mainland where I live.

But as it turns out, Boots is right.

Things do happen.

And one surprise.

I meet George.

2

Even Steven

So here is the next day of my life. I get up early. No Theo. But of course this is my story. Theo brings his heavy bag of books to read, always fearful that the small island library will not have the books he wants.

Theo is the watcher and listener of my story.

Jake is in the kitchen with Tess. He has lots of toast on the counter and is making his famous poached eggs in his six-cup poached egg pan. He tosses bits of toast over his head every so often for Tess. She runs and scrambles and jumps to catch the pieces.

He does this every morning “for her exercise,” as he puts it with a smile.

Actually, it is Jake’s exercise.

Jake looks sideways at me. He pushes a plate of toast on the counter—waiting for the egg that will sit on it.

“What are you doing this morning?” he asks.

He has a sly look to him.

He tosses a piece of toast over his head, and I reach over, catch it, and give it to Tess.

“Nothing,” I say to Jake. “You have something exciting planned? Right?”

“Yep, I do.”

He slips a perfectly poached egg onto my toast.

“I know that because we’re kindred spirits,” I say.

He looks sideways at me again. “No. I already have a kindred spirit. I’m your pal, Louisa. When you were a baby and I walked into the room, your eyes lit up. Just seeing me!”

This makes me smile. I remember when I was four years old I had a temper tantrum. My parents sent me upstairs to “think about it.”

Jake came upstairs and into my room. “That was a good tantrum,” he said. “And you were right to have it. We learn a lot from suffering a bit afterward.”

I never forgot that. Jake is right. We were pals even then.

“Where’s Boots?”

“She went shopping with her friend Talking Tillie. I don’t have much time for my project.”

“Project? What project?”

He looks at me. “Come on, Louisa. Hurry and eat up.”

He hurries out the screen door, letting it slap behind him.

Project?

I pick up a piece of toast and share it with Tess. I take two quick bites. The rest will wait for me.

And we both go out the door.

There is early-morning sun, but no Jake.

“Jake?” I call.

“In here,” he calls back.

I see the garage door is open. Tess and I walk over and look inside.

Jake is pushing a soft rag over the gleaming black car.

And standing next to the car is a boy a bit taller than I am.

His hair is the black color of Jake’s car. His skin is brown.

We stare at each other.

Jake looks up.

“This is Louisiana. Louisa, this is my friend George.”

Tess goes over to George and he bends down to pat her. Then he straightens up.

I open my mouth, but nothing comes out.

George has no idea what I am actually thinking and can’t say to him.

Jake looks at George, then at me.

“Louisiana is probably thinking that you are pretty swell.”

George smiles.

I can feel myself blush. I am startled.

Jake knows.

“Then I’ll admit I have never seen anyone with the beautiful red color of your tumbling hair,” says George.

Tumbling hair?

I can’t help smiling back at George.

“Even steven,” I say.

“Even steven,” George repeats.

“Okay,” says Jake loudly. “Now that we all like each other, get in the car! Boots will be back in an hour. We can only do this when Boots is gone. She wouldn’t approve of us driving when we drive on the road.”

“Where are we going?” I ask.

“This is my project,” says Jake. “Get in. I’m teaching George how to drive my car.”

Jake opens the back door of his beautiful car. I get in. Tess surprises me by jumping in beside me.

She’s done this before.

Jake sits on the passenger side, not the driver’s side.

George gets in the driver’s seat, starts the car, and backs out of the garage, down the driveway, and onto the road.

“Still no seat belts,” I say from the back seat.

George looks at me in the rearview mirror. I can tell he’s amused.

“No seat belts,” says Jake. “This is a l938 car. Same age as I am.”

We drive up the road.

“Is George allowed to drive on the road?” I ask.

“Not legally!” says Jake cheerfully.

Then we avoid one of the neighbors’ chickens running down the road. We turn and go up into the land behind Jake’s house.

Beside me, Tess wags her tail and looks out the window, leaving dog nose marks there.

We drive around the field and the pond, George working the clutch and brake smoothly.

A heron flies up from the pond, then flies back again.

When we return home, down off the grass hill and onto the road, we go back to the garage.

George grins at me.

“Even steven,” he says, holding up his hand.

I put my hand against his.

His hand is cool.

“Even steven,” I say.

We are friends.

3

The Mirror

After George leaves, Jake and I walk back to the house.

“Boots doesn’t know George and I drive the car when she’s away,” says Jake.

“You think?” I ask.

“She wouldn’t approve,” says Jake. “Don’t tell her.”

“I don’t know if I can do that, Jake.”

“You can try,” says Jake.

I remember saying to Boots that I could try to stop change.

“George is your kindred spirit,” I say.

Jake smiles. “He is.”

“And Boots is your soul mate,” says Jake.

I reach over to hold his hand. “And you are my pal,” I say.

“And here is my secret. Boots doesn’t know that I plan to give George the car. He loves it the way I do.”

“But what about Boots driving?”

“She would never drive that car. She only drove once, and never again. And she knows nothing about gears and clutches.”

Jake and I go into the kitchen where Theo is drinking orange juice, his eyes bleary from sleep.

Suddenly I stop and look at myself in the mirror hung by the door. I look at my long mop of red hair. I stare at the look of me.

“What’s Lou doing?” asks Theo.

Jake turns and comes over to stand behind me as we both see ourselves in the mirror.

“Louisa is, I believe, thinking of herself as beautiful for the first time ever,” he says.

“She’s always been beautiful,” says Theo.

“Not as beautiful as today,” my pal Jake says to me in the mirror.

I am not looking at me, actually.

I’m looking at my “tumbling” red hair.

Boots comes home with Talking Tillie. They carry bags in. We all go out to help, Tillie talking about the sky this morning, the rain in the middle of the night, “and my cat who caught three—three, count them!—mice in the night and left them on the rug for me to step on in the morning.”

When Talking Tillie is gone, Theo and I put away the groceries. Jake goes out to the garage.

“I’m going up to pick a new book to read,” says Theo.

“How many books did you bring?” I ask.

“Forty-eight,” says Theo, bounding up the stairs.

Boots laughs.

“What’s new?” asks Boots, peering at me.

I shrug.

“George was here,” I say lightly.

“Aha,” she says. “And did Jake and George drive on the road and up around the pond?”

“You know about that?”

Boots looks closely at me.

“Oh, right. You know everything,” I say.

“I do. Plus, Jake never realizes that the hood of his car is warm when he’s been off driving with George.”

“You’re sneaky, Boots.”

“I am.”

“I went too,” I confess. “And Tess. When he can’t see to drive anymore, maybe you can drive,” I say to Boots.

“Not me. Not Jake’s car. He loves the car as much as he loves me. I’m not about to change now.”

“But, Boots, you’re the one who told me that change could be exciting. An adventure!”

Boots stares at me.

“Gotcha,” I say.

“Gotcha,” says Boots in a low voice.

She leans back in her chair and stares at me.

I thought about saying “even steven” to George and George saying “even steven” back to me with our hands together.

I was quiet. Boots was quiet.

I didn’t tell Boots that George loved my “tumbling” hair.

I didn’t say I thought George was beautiful.

“Did you drive a car when you were young, or did Jake drive when you met him?” I ask.

Boots smiles. “Jake and I met in middle school. We fell in love across the classroom. Doing homework together. Walking home after school, laughing all the way. I was thirteen when I fell in love. How old are you?”

“Almost twelve,” I say.

“Imagine that,” says Boots. “Falling in love at your age.”

I say nothing.

“And you never drove a car?” I ask.

“Once I did. But not Jake’s car. And Jake would never have the patience to teach me.”

I grin.

“But George would,” I say in a low voice.

Boots doesn’t say anything for a long time.

Theo comes back to the kitchen with an armful of books. He drops them on the table, sorting them into piles of “yes, I’ll read now” and “later.”

I think about Boots and Jake falling in love so young.

No one I ever heard of fell in love at age twelve.

So here is the question of the day: Why, when I look in the mirror now, do I suddenly look beautiful for the very first time in my life? Is it a mistake somehow? A strange moment that will slip away like clouds?