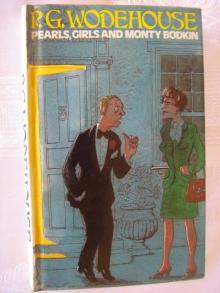

Pearls, Girls and Monty Bodkin

P. G. Wodehouse

P. G. WODEHOUSE

BARRIE & JENKINS

Chapter One 3

Chapter Two 10

Chapter Three 25

Chapter Four 38

Chapter Five 46

Chapter Six 60

Chapter Seven 76

Chapter Eight 91

Chapter Nine 100

Chapter Ten 114

Chapter Eleven 132

Chapter Twelve 147

Chapter One

As always when the weather was not unusual the Californian sun shone brightly down on the Superba-Llewellyn motion picture studio at Llewellyn City. Silence had gripped the great building except for the footsteps of some supervisor hurrying back to resume his supervising or the occasional howl from the writer's ghetto as some author with a headache sought in vain to make sense of the story which had been handed to him for treatment. It was two-thirty of a summer afternoon, and this busy hive of industry generally tended to slacken off at that hour.

In the office bearing on its door the legend

ADVISER FOR PRODUCTIONS

and in smaller letters down in the left-hand corner the name

M. Bodkin

Sandy Miller, M. Bodkin's secretary, was waiting for her overlord to return from lunch.

Secretaries in Hollywood are either statuesque and haughty or small, pretty and vivacious. Sandy belonged to the latter class. But though a cheerful little soul as a general rule, as ready with a laugh as a television studio audience, at that moment she had allowed a frown to mar the smoothness of the alabaster brow which all Hollywood secretaries have to have. She was thinking, as she so often did when in meditative mood, how much she loved M. (standing for Monty) Bodkin.

It had come on quite suddenly one afternoon when they were sharing a beef stew Bette Davis at the canteen, and had grown steadily through the months till now the urge to stroke his butter-coloured hair had become almost irresistible. And what was causing her to frown was the thought of how foolish it had been of her to allow herself to get into this condition with one whose heart was so plainly bestowed elsewhere. There was a photograph on his desk of a robust girl signed 'Love. Gertrude', and photographs endorsed like that cannot be ignored. They mean something. They have a message. This message had not escaped Sandy, particularly on the morning when she had caught him kissing the thing. (He had said he was blowing a speck of dust off the glass, but this explanation, though specious, had not convinced her.)

Who this Gertrude was she had not been informed, for M. Bodkin was reticent about his private affairs. Of her own she had concealed nothing from him. In the long afternoons when business was slack and there was the opportunity of exchanging confidences she had revealed the whole Sandy Miller Story—the childhood in the small Illinois town, the leisurely passage through high school, the lucky break when rich Uncle Alexander, doing the square thing by his goddaughter, had put her through secretarial college, the graduation from same, the various jobs, some good, some not so good, and finally the coming to Hollywood because she had always wanted to see what it was like there. And almost all she knew of Monty was that he had a good appetite and a freckle on his nose. It irritated her constantly.

He came in at this moment, greeted her with his customary cordiality, cast a loving glance at the robust girl on the desk and took a seat.

It is difficult to say offhand what ought to be the aspect of a production adviser at a prominent Hollywood studio. Of Monty you could only state that he did not look like one. His pleasant, somewhat ordinary face suggested amiability rather than astuteness. In the West End of London—say at the Drones Club in Dover Street, of which he was a popular member—you would have encountered him without surprise. In the executive building of the Superba-Llewellyn he seemed out of place. You felt he ought not to-be there. Ivor Llewellyn, the president of the organisation, had this feeling very strongly. There was an ornamental lake on the Superba-Llewellyn lot, and it was his opinion that his production adviser ought to be at the bottom of it with a stout brick attached to his neck. Though not as a rule a lavish man, he would gladly have supplied brick and string free of charge.

Refreshed by lunch, Monty was plainly in jovial mood. He nearly always was, and it was this unfailing euphoria of his that twisted the knife in Mr. Llewellyn's bosom, he holding the view that a man who had chiselled his way into the Superba-Llewellyn as Monty had done ought at least to have the decency to behave as if his conscience were gnawing him.

'Sorry I'm late,’’ he said. I got entangled in some particularly adhesive spaghetti and have only just succeeded in hacking my way through to safety. Anything sensational happened in my absence?'

'No.'

'No earthquakes or other Acts of God?'

'No.'

'No trouble brewing in the writers' kraals? The natives not restless?'"

'No.'

There had been an unwonted brusqueness in Sandy's monosyllabic replies, and Monty regarded her with concern. They gave him the impression that she had something on her mind. He was very fond of her—in a brotherly way, of course, to which even Gertrude Butterwick, always inclined to look squiggle-eyed at his female friends, could not have taken exception— and it pained him to think that anything was worrying her.

'You seem distrait, my poppet. Are you musing on something?'

It seemed to Sandy that at last an opportunity had presented itself for extracting confidences from this man of mystery. Never till now had their conversation taken a turn which provided her with such an admirable cue.

'If you really want to know,’ she said, ‘I was musing on you.’’

'You were? I'm flattered.’

'I was trying to figure out what, you were doing in Llewellyn City.’’

'I'm a production adviser. See door.’

'Exactly. That's what puzzled me. At most studios, from what one hears, you have to he a nephew or a brother-in-law of the man up top to be given an important position like that. Yet here you are, no relation even by marriage, production advising away like a house on fire. And you told me you had had no previous experience.’’

'That's good, don't you think? I bring a fresh mind to the job.’

‘But how did you get the job?'

'I met Llewellyn on the boat coming over from England.'

'And he said "I like your face, my boy. Come and take charge of my productions"?'

'It amounted to that.’

'He must have liked your face very much.’

'Can you blame him? Of course there was another factor which was of assistance to me in the negotiations.’

'What was that?'

'Never mind.’

'But I do mind. What was it?'

'He had urgent need of something that was in my possession. In order to induce me to part with it he was obliged to meet my terms. That's how business deals are always conducted.'

'What was it he wanted?'

'If I tell you, will you promise to ask no more questions?'

'All right.'

'Sacred word?'

'Sacred word.'

'Very well. It was a mouse.'

'What!'

'That's what it was.'

'But I don't understand. How do you mean? Why did he want a mouse?'

'You promised not to ask any more questions.'

'But I didn't think you were going to say a mouse.'

'In this world we must be prepared for anybody to say anything.'

'But a mouse. Why?'

'The subject is closed.'

'You aren't going to explain?'

'Not a word. My lips are sealed, like those of a clam.'

Sandy's exasperation became too much for her. If she had had any more lethal weapo

n than a small notebook, she would have thrown it at him. She burst into a tidal wave of eloquence.

'Shall I tell you something that may be of interest? You make me sick. Here am I, trying to collect material for the Memoirs I shall be writing one of these days, and what ought to be the most interesting part of them, the time I spent working for the great Monty Bodkin in Hollywood, won't amount to a hill of beans because the great Monty Bodkin is one of those strong silent Englishmen who don't utter. They are generally described—correctly—as dumb bricks. All I shall be able to tell my public is that on the rare occasions when you did break your Trappist vows you talked as if you had a potato in your mouth.'

Monty started. The shaft had pierced his armour.

'A potato?'

'Large and boiled.'

'You're crazy.'

'All right. I'm just telling you.'

The discussion threatened to become heated. Monty, always the man of peace, raised a restraining hand.

'We mustn't brawl. Merely remarking that my enunciation is more like a silver bell than anything, ask anybody, I will tactfully divert the conversation to other topics, to take one at random. Pop Llewellyn. He was at the canteen.'

'Oh?'

'He was tucking into a pudding, or dessert as you would call it, of obvious richness, all cream and sugar and stuff.'

'Oh?'

'Shovelling it into himself like a starving Eskimo. I was sorry that our relations were not such as to make it possible for me to warn him it was adding pounds to his already impressive weight, I couldn't have done that, of course. He wouldn't have taken it kindly and would probably have bitten me in the leg.'

'Oh?'

'You do keep saying "Oh?", don't you? It's an odd thing about Llewellyn.’ said Monty thoughtfully. ‘I've been seeing him daily for a year, and you'd think I'd have got immune to him by this time, but whenever we meet my bones still turn to water and Dow Jones registers another sharp drop in my morale. I shuffle my feet. I twiddle my fingers. My pores open and I break into a cold sweat, if you will pardon the expression. Does he affect you in this way?'

'I've never met him.'

'You're lucky.'

'I once did some work for Mrs. Llewellyn.'

'What's she like? Meek and crushed, I suppose?'

'Meek and crushed nothing. She's the boss. At her command he jumps through hoops and snaps lumps of sugar off his nose. It's like that Ben Bolt poem we used to learn in high school. “He weeps with delight when she gives him a smile and trembles with fear at her frown.”'

‘I used to recite that as a youngster.’

‘It must have sounded wonderful.'

'I believe it did. But really you astound me. I can't imagine Llewellyn trembling with fear. To me he has always seemed like one of those unpleasant creatures in the Book of Revelation. She must be a very remarkable woman.'

'She is.'

'No doubt she is the motivating force behind this trip to Europe.'

'This what to where?'

'They are crossing the Atlantic shortly on a vacation.' Who told you that?'

'A fellow I met in the canteen who looked as if he might be a writer of additional dialogue or the man in charge of the wind machine. They'll be away for quite a while.'

'It won't have to. I also am leaving.'

'What!'

You could have said that Monty's words had given Sandy a shock, and you would have been perfectly right. Her eyes had widened and her attractive jaw fallen a full inch. In her optimistic moments she had sometimes hoped that if there association continued uninterrupted, propinquity might do the work it is always supposed to do, causing the man she loved to forget the robust girl he had left behind him, but at this announcement the hope curled up and died.

Speech came from her in a gasp.

'You're quitting?'

'As of even date.'

'Going back to England?'

'That's right. And I shall want you to help me with ray letter of resignation. So take pencil and notebook and let's get at it.'

Sandy was a girl of mettle. The dreams she had allowed herself to dream lay in ruins about her, but she spoke composedly.

'How far have you got?'

'"Dear Mr. Llewellyn".'

'Good start.'

'So I thought. But now comes the part where I need your never-failing sympathy, encouragement and advice. The wording has to be just right.'

'I don't see why. From what you were telling me, he'll probably be delighted to get rid of you.'

'He will. I shall be surprised if he doesn't go dancing in the streets and ordering an ox to be roasted whole in the market place. But don't forget that sudden joy can be as dangerous as sudden anguish. Llewellyn is now loaded to the brim with that creamy pudding or desert, and the announcement on a full stomach that I am leaving him, if not broken gently, might prove fatal.'

Chapter Two

The smoking-room of the Drones Club always started to fill up as the hour of lunch approached, and today a group of members had assembled there, like antelopes or whatever the fauna are that collect in gangs around water holes, in order to enjoy the pre-prandial aperitif. It was as the various beverages were brought in and distributed that a Whisky Sour, having taken the first lifegiving sip, said:

'Oh, I say, who do you think I met in Piccadilly last night?'

'Who?' enquired a Martini-with-small-onion-not-an-olive.

'Monty Bodkin.'

'Monty Bodkin? You couldn't have!'

‘I did.'

'But he's in Hollywood.' 'He's back.'

'Oh, he's back?' said the. Martini, relieved. I thought for a moment you must have seen his astral body or whatever they call it. I believe it often happens that way. A chap hands in his dinner pail in America or wherever it may be and looks in on a pal in London to report. It really was Monty, was it?'

'Looking bronzed and fit.’

'How long was he in Hollywood?'

'A year. His contract was for five years, but one was all he needed.'

'Why?'

'Why what?'

'Why did he only need one year?'

'Because that would satisfy the conditions laid down by her father.'

'Whose father?'

'Gertrude Butterwick's.'

'You couldn't make this a bit easier, could you?' asked a Screwdriver with dark circles under his eyes. I was up rather late last night and am not feeling at my best this morning. Who, to start with, is Gertrude Butterwick?'

'The girl Monty's engaged to.'

'Reggie Tennyson's cousin,' said a well-informed Manhattan. 'Plays hockey.'

The Screwdriver winced. The sorrows he had been trying to drown on the previous night had been caused by a girl who played hockey. He had been rash enough to allow his fiancée to persuade him to referee a match in which she was taking part, and she had broken the engagement because on six occasions he had penalised her—unjustly, she maintained—for being offside.

'How do you mean, the conditions laid down by her father?' asked a puzzled Gimlet.

'Just that.'

'He laid down conditions?'

'Yes.'

'Her father did?'

'Yes.'

'Gertrude Butterwick's father?'

'Yes.'

'Sorry. I don't get it.'

'It's perfectly simple. I had it all from Monty last night over a Welsh rarebit and a bottle of the best. Extraordinarily interesting story, rather like Jacob and Rachel in the Bible, except that Jacob had to serve seven years to get Rachel, while Monty only had to serve one.'

The Screwdriver moaned faintly and passed a piece of ice over his forehead. The Whisky Sour proceeded.

'I think it was at a lunch or a dinner that he met Gertrude and decided that she was what the doctor ordered. Apparently she took the same view of him, because it wasn't more than a week or so before they became engaged. And then, just as it looked as if all they had to do was collect the bridesmaids, order the cake and sign up the Bishop an

d assistant clergy, along came the sleeve across the windpipe. Her father refused to give his consent to their union.'

The Gimlet was visibly moved, as were all those present except the Screwdriver, who was still busy with his ice.

'He did what?'

'Wouldn't give his consent.'

'But surely you don't have to have father's consent in these enlightened days?'

'You do if you're Gertrude Butterwick. She's a throwback to the Victorian age. She does what Daddy tells her.'

'Comes of playing hockey.’ said the Screwdriver.

'Monty, of course, was as surprised, bewildered and taken aback as you are. He pleaded with her to ignore the memo from the front office and elope, but she would have none of it. Some nonsense about her father having a weak heart and it would kill him if his daughter disobeyed him.'

'Silly ass.'

'Indubitably. I have it from Reggie Tennyson that Pop Butterwick not only looks like a horse but is as strong as one. Still, there it was.’

'No daughter of mine shall ever be allowed to touch a hockey stick.’ said the Screwdriver. 'I shall be very firm about this.’

'But why wouldn't her father give his consent?' asked a Comfort-on-the-rocks. 'Monty's got all the money in the world.'

'That,’ said the Whisky Sour, 'was just the trouble. He was left the stuff by an aunt, and old Butterwick is one of those fellows who go into business at the age of sixteen and take a dim view of inherited money. He said Monty was a rich young waster and no daughter of his was going to marry him.'

'So that was that.'

'As it happened, no. Monty reasoned with the blister, who eventually relented to the extent of saying that if he proved himself by earning his living for a year, the wedding bells would ring out. So Monty got a job with the Superba-Llewellyn motion picture people at Llewellyn City, Southern California.'

It hurt the Screwdriver to move his head, but he did so in order to cast a stern glance at the speaker. He resented a story sloppily told.

'You say "Monty got a job with the Superba-Llewellyn people" in that offhand way, as if it were the simplest thing in the world to get taken on by a motion picture organisation, whereas everybody knows that if you aren't the illegitimate son of one of the principal shareholders, you haven't a hope. How did Monty worm his way in?'