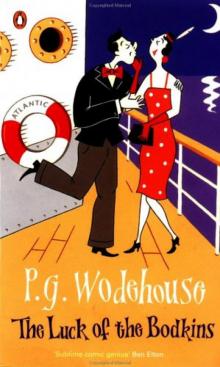

The Luck of the Bodkins

P. G. Wodehouse

Luck of the Bodkins

P G Wodehouse

Published: 2010

Tags: Humour

Humourttt

* * *

.

SUMMARY:

Things on board the R. M. S. Atlantic are terribly, terribly complicated. Monty Bodkin loves Gertrude, who thinks he likes Lotus Blossom, a starlet, who definitely adores Ambrose, who thinks she has a thing for his brother Reggie, who is struck by Mabel Spence, sister-in-law of Ikey Llewellyn, but hasn't the means to marry her. It will, indeed, take the luck of the Bodkins to sort this all out.

P. G. Wodehouse

The Luck of the Bodkins

Penguin Books

Penguin Books Ltd, Harmondsworth, Middlesex, England Penguin Books, 40 West 23rd Street, New York, New York 10010, U.S.A. Penguin Books Australia Ltd, Ringwood, Victoria, Australia

Penguin Books Canada Limited, 2801 John Street, Markham, Ontario, Canada L3R 1B4 Penguin Books (N.Z.) Ltd, 182-190 Wairau Road, Auckland 10, New Zealand

First published 1935

Published in Penguin Books 1954

Published in Penguin Books in the United States of America by arrangement with Scott Meredith Literary Agency, Inc. Reprinted 1962, 1973,1975, 1976, 1978,1979, 1981, 1983

Copyright 1935 by P. G. Wodehouse Copyright © P. G. Wodehouse, 1963 All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America by Kingsport Press, Inc., Kingsport, Tennessee Set in Times Roman

All the characters in this book are purely imaginary and have no relation whatsoever to any living person.

Except in the United States of America, this book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publisher's prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser

Chapter 1

I

Into the face of the young man who sat on the terrace of the Hotel Magnifique at Cannes there had crept a look of furtive shame, the shifty, hangdog look which announces that an Englishman is about to talk French. One of the things which Gertrude Butterwick had impressed upon Monty Bodkin when he left for this holiday on the Riviera was that he must be sure to practise his French, and Gertrude's word was law. So now, though he knew that it was going to make his nose tickle, he said:

'Er, garcon.'

'M'sieur?'

'Er, garcon, esker-vous avez un spot de l'encre et une piece de papier - note-papier, vous savez - et une enveloppe et une plume?’

'Ben, m'sieur.’

The strain was too great. Monty relapsed into his native tongue.

‘I want to write a letter,' he said. And having, like all lovers, rather a tendency to share his romance with the world, he would probably have added 'to the sweetest girl on earth1, had not the waiter already bounded off like a retriever, to return a few moments later with the fixings.

'Via, sir! Zere you are, sir,’ said the waiter. He was engaged to a girl in Paris who had told him that when on the Riviera he must be sure to practise his English. 'Eenk - pin - pipper -enveloppe - and a liddle bit of bloddin-pipper.'

'Oh, merci,' said Monty, well pleased at this efficiency. Thanks. Right ho.'

'Right ho, m'sieur,' said the waiter.

Left alone, Monty lost no time in spreading paper on the table, taking up the pen and dipping it in the ink. So far, so good. But now, as so often happened when he started to writ© to the girl he loved, there occurred a stage wait. He paused, wondering how to begin.

It always irked him, this unreadiness of his as a correspondent. He worshipped Gertrude Butterwick as no man had ever worshipped woman before. Closeted with her, his arm about her waist, her head nestling on his shoulder, he could speak of his love eloquently and well. But he always had the most extraordinary difficulty in starting getting the stuff down on paper. He envied fellows like Gertrude's cousin, Ambrose Tennyson. Ambrose was a novelist, and a letter like this would have been pie to him. Ambrose Tennyson would probably have covered his eight sheets and be licking the envelope now.

However, one thing was certain. Absolutely and without fail he must get something off by today's post. Apart from picture postcards, the last occasion on which he had written to Gertrude had been a full week before, when he had sent her that snapshot of himself in bathing costume on the Eden Rock. And girls, he knew, take these things to heart.

Chewing the pen and looking about him for inspiration, he decided to edge into the thing with a description of the scenery.

‘Hotel Magnifique, 'Cannes,

'France, A.M

'My Darling Old Egg,

'I'm writing this on the terrace outside the hotel. It's a lovely day. The sea is blue -'

He stopped, perceiving that he had missed a trick. He tore up the paper and began again:

Hotel Magnifique, 'Cannes,

'France, A.M.

'My Precious Dream-Rabbit,

'I'm writing this on the terrace outside the hotel. It's a lovely day, and how I wish you were with me, because I miss you all the time, and it's perfectly foul to think that when I get back you will have popped off to America and I shan't see you for ages. I'm dashed if I know how I shall stick it out

This terrace looks out on the esplanade. The Croisette they call it -1 don't know why. Silly, but there it is. The sea is blue. The sand is yellow. One or two yachts are mucking about. There are a couple of islands over to the left, and over to the right some mountains.'

He stopped once more. This, he felt, was about as much as the scenery was good for in the way of entertainment value. Carry on in the same vein, and he might just as well send her the local guide-book. What was required now was a splash of human interest. That gossipy stuff that girls like. He looked about him again, and again received inspiration.

A fat man, accompanied by a slim girl, had just come out on to the terrace. He knew this fat man by sight and reputation, and he was a personality well worth a paragraph in anybody's letter. Ivor Llewellyn, President of the Superba-Llewellyn Motion Picture Corporation of Hollywood.

He resumed:

There aren't many people about at this time of day, as most of the lads play tennis in the morning or go off to Antibes to bathe. On the skyline, however, has just appeared a bird you may have heard of - Ivor Llewellyn, the motion picture bloke.

'At least, if you haven't heard of him, you've seen lots of his pictures. That thing we went to see my last day in London was one of his, the thing called - well, I forget what it was called, but there were gangsters in it and Lotus Blossom was the girl who loved the young reporter.

lie's parked himself at a table not far away, and is talking to a female.'

Monty paused again. Re-reading what he had written, he found himself wondering if it was the goods, after all. Gossipy stuff was all very well, but was it quite wise to dig up the dead past like this? That mention of Lotus Blossom ... on the occasion referred to, he recalled, his open admiration of Miss Blossom had caused Gertrude to look a trifle squiggle-eyed, and it had taken two cups of tea and a plate of fancy cakes at the Ritz to pull her round.

With a slight sigh, he wrote the thing again, keeping in the scenery but omitting the human interest. It then struck him that it would be a graceful act, and one likely to be much appreciated, if he featured her father for a moment. He did not like her father, considering him, indeed, a pig-headed old bohunkus, but there are times when it is polite to sink one's personal prejudices.

'As I sit here in this lovely sunshine, I find myself brooding a good deal on your dear old father. How is he? (Tell him I asked, will you?) I hope

he has been having no more trouble with his -

Monty sat back with a thoughtful frown. He had struck a snag. He wished now that he had left her dear old father alone. For the ailment from which Mr Butterwick suffered was that painful and annoying malady sciatica, and he hadn't the foggiest how to spell it,

II

If Monty Bodkin had been, like his loved one's cousin Ambrose Tennyson, an artist in words, he would probably have supplemented his bald statement that Mr Ivor Llewellyn was talking to a female with the adjective 'earnestly', or even some such sentence as 'I should imagine upon matters of rather urgent importance, for the dullest eye could discern that the man is deeply moved.'

Nor, in writing thus, would he have erred. The motion picture magnate was, indeed, agitated in the extreme. As he sat there in conference with his wife's sister Mabel, his brow was furrowed, his eyes bulged, and each of his three chins seemed to compete with the others in activity of movement As for his hands, so briskly did they weave and circle that he looked like a plump Boy Scout signalling items of interest to some colleague across the way.

Mr Llewellyn had never liked his wife's sister Mabel - he thought, though he would have been the first to admit it was a near thing, that he disliked her more than his wife's brother George - but never had she seemed so repulsive to him as Dow. He could not have gazed at her with a keener distaste if she had been a foreign star putting her terms up.

‘What!'he cried.

There had been no premonition to soften the shock. When on the previous day that telegram had come from Grayce, his wife, who was in Paris, informing him that her sister Mabel would be arriving in Cannes on the Blue Train this morning, he had been annoyed, it is true, and had grunted once or twice to show it, but he had had no sense of impending doom. After registering a sturdy resolve that he was darned if he would meet her at the station, he had virtually dismissed the matter from his mind. So unimportant did his wife's sister Mabel's movements seem to him.

Even when she had met him in the lobby of the hotel just now and had asked him to give her five minutes in some quiet spot on a matter of importance he had had no apprehensions, supposing merely that she was about to try to borrow money and that he was about to say he wouldn't give her any.

It was only when she hurled her bombshell, carelessly powdering her (to most people, though not to her brother-in-law) attractive nose the while, that the wretched man became conscious of his position.

'Listen, Ikey,' said Mabel Spence, for all the world as if she were talking about the weather or discussing the blue sea and yellow sand which had excited Monty Bodkin's admiration, "we've got a job for you. Grayce has bought a peach of a pearl necklace in Paris, and she wants you, when you sail for home next week, to take it along and smuggle it through the Cus< toms.'

‘What!'

'You heard.’

Ivor Llewellyn's lower jaw moved slowly downward, as if seeking refuge in his chins. His eyebrows rose. The eyes beneath them widened and seemed to creep forward from their sockets. As President of the Superba-Llewellyn Motion Picture Corporation, he had many a talented and emotional artist on his pay-roll, but not one of them could hav^ registered horror with such unmistakable precision.

‘What, me?'

‘Yes, you.’

'What, smuggle necklaces through the New York Customs?’ ‘Yes.'

It was at this point that Ivor Llewellyn had begun to behave like a Boy Scout. Nor can we fairly blame him. To each man is given his special fear. Some quail before income-tax assessors, others before traffic policemen. Ivor Llewellyn had always had a perfect horror of Customs inspectors. He shrank from the gaze of their fishy eyes. He quivered when they chewed gum at him. When they jerked silent thumbs at his cabin trunk he opened it as if there were a body inside.

‘I won't do itl She's crazy.'

'Why?'

'Of course she's crazy. Doesn't Grayce know that every time an American woman buys jewellery in Paris the bandit who sells it to her notifies the Customs people back home so that they're waiting for her with their hatchets when she lands?'

That's why she wants you to take it. They won't be looking out for you.'

'Pshaw! Of course they'll be looking out for me. So I'm to get caught smuggling, am I? I'm to go to jail, am I?'

Mabel Spence replaced her powder-puff.

‘You won't go to jail. Not,' she said in the quietly offensive manner which had so often made Mr Llewellyn wish to hit her with a brick, 'for smuggling Grayce's necklace, that is. It's all going to be perfectly simple.’

'Oh, yeah?'

'Sure. Everything's arranged. Grayce has written to George. He will meet you on the dock.'

'That.' said Mr Llewellyn, 'will be great. That will just make my day.'

'As you come off the gang-plank, he will slap you on the back.' Mr Llewejlyn started. ·George will?' ‘Yes.'

'Your brother George?' ‘Yes.'

'He will if he wants a good poke in the nose,' said Mr Llewellyn.

Mabel Spence resumed her remarks, still with that rather trying resemblance in her manner to a nurse endeavouring to reason with a half-witted child.

'Don't be so silly, Ikey. Listen. When I bring the necklace on board at Cherbourg, I am going to sew it in your hat. When you go ashore at New York, that is the hat you will be wearing. When George slaps you on the back, it will fall off. George will stoop to pick it up, and his hat will fall off. Then he will give you his hat and take yours and walk off the dock. There's no risk at all.'

Many men's eyes would have sparkled brightly at the ingenuity of the scheme which this girl had outlined, but Ivor Llewellyn was a man whose eyes, even under the most favourable conditions, did not sparkle readily. They had been dull and glassy before she spoke, and they were dull and glassy now. If any expression did come into them, it was one of incredulous amazement.

'You mean to say you're planning to let your brother George get his hooks on a necklace that's worth - how much is it worth?’

'About fifty thousand dollars.'

'And George is to be let walk off the dock with a fifty thousand dollar necklace in his hat? George?' said Mr Llewellyn, as if wondering if he could have caught the name correctly. 'Why, I wouldn't trust your brother George alone with a kid's money-box.'

Mabel Spence had no illusions about her flesh and blood. She saw his point. A perfectly sound point. But she remained calm.

'George won't steal Grayce's necklace,'

'Why not?'

'He knows Grayce.'

Mr Llewellyn was compelled to recognize the force of her argument. His wife in her professional days had been one of the best-known panther-women on the silent screen. Nobody who had seen her in her famous role of Mimi, the female Apache in When Paris Sleeps, or who in private life had watched her dismissing a cook could pretend for an instant that she was a good person to steal pearl necklaces from.

'Grayce would skin him.'

A keen ear might have heard a wistful sigh proceed from Mr Llewellyn's lips. The idea of someone skinning his brother-in-law George touched a responsive chord in him. He had felt like that ever since his wife had compelled him to put the other on the Superba-Llewellyn pay-roll at a thousand dollars a week as a production expert.

'I guess you're right,' he said. 'But I don't like it. I don't like it, I tell you, darn it. It's too risky. How do you know something won't go wrong? These Customs people have their spies everywhere, and I'll probably find, when I step ashore with that necklace -'

He did not complete the sentence. He had got thus far when there was an apologetic cough from behind him, and a voice spoke:

'I say, excuse me, but do you happen to know how to spell "sciatica"?'

III

It was not immediately that Monty Bodkin had decided to apply to Mr Llewellyn for aid in solving the problem that was vexing him. Possibly this was due to a nice social sense which made him shrink from forcing himself upon a stranger, possibly to the fact that some instinct told him that when yo

u ask a motion-picture magnate to start spelling things you catch him on his weak spot. Be that as it may, he had first consulted his friend the waiter, and the waiter had proved a broken reed. Beginning by affecting not to believe that there was such a word, he had suddenly uttered a cry, struck his forehead and exclaimed: ‘Ah! La sciatique!'

He had then gone on to make the following perfectly asinine speech:

'Comme ca, m'sieur. Like zis, boy. Wit' a ess, wit' a say, wit' a ee, wit' a arr, wit' a tay, wit' a ee, wit' a ku, wit' a uh, wit' a ay. Via! Sciatique.'

Upon which, Monty, who was in no mood for this sort of thing, had very properly motioned him away with a gesture and gone off to get a second opinion.

His reception, on presenting his little difficulty to this new audience, occasioned him a certain surprise. It would not be too much to say that he was taken aback. He had never been introduced to Mr Llewellyn, and he was aware that many people object to being addressed by strangers, but he could not help feeling a little astonished at the stare of horrified loathing with which the other greeted him as he turned. He had not seen anything like it since the day, years ago, when his Uncle Percy, who collected old china, had come into the drawing-room and found him balancing a Ming vase on his chin.

The female, fortunately, appeared calmer. Monty liked her looks. A small, neat brunette, with nice grey eyes. 'What,' she inquired, 'would that be, once again?' ‘I want to spell "sciatica".' 'Well, go on,' said Mabel Spence indulgently. 'But I don't know how to.'

‘I see. Well, unless the New Deal has changed it, it ought to be s-c-i-a-t-i-c-a.' 'Do you mind if I write that down?’ ‘I’d prefer it.'

'. . . -t-i-c-a. Right. Thanks,' said Monty warmly. 'Thanks awfully. I thought as much. That ass of a waiter was pulling my leg. All that rot about "with a ess, with a tay, with a arr", I mean to say. Even I knew there wasn't an "r" in it. Thanks. Thanks frightfully.’