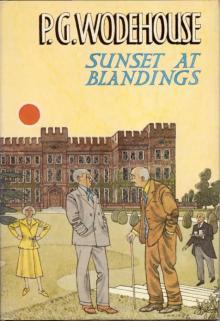

Sunset at Blandings

P. G. Wodehouse

SUNSET AT

BLANDINGS

P. G. WODEHOUSE

With Notes and Appendices

by

RICHARD USBORNE

Illustrations by Ionicus

BOOK CLUB ASSOCIATES

LONDON

CONTENTS

Sunset at Blandings

Appendices by Richard Usborne:

Work in Progress

The Castle and its Surroundings

The Trains Between Paddington and Market Blandings

CHAPTER ONE

SIR JAMES PIPER, England’s Chancellor of the Exchequer, sat in his London study staring before him with what are usually called unseeing eyes and snorting every now and then like somebody bursting a series of small paper bags. Sherlock Holmes, had he seen him, would have deduced instantly that he was not in a good temper.

‘Elementary, my dear Watson,’ he would have said. ‘Those snorts tell the story.’

And Claude Duff, Sir James’s junior secretary, who had been intending to ask him if he could have the day off to go and see his aunt at Eastbourne, heard these snorts and changed his mind. He was a nervous young man.

Holmes would have been right. Sir James had been in the worst of humours ever since his sister Brenda had told him that he was to go to Blandings Castle, the Shropshire seat of Clarence, Earl of Emsworth, when he had been planning a fishing holiday in Scotland. And what was worse, he had got to take a girl with him and deliver her to the custody of Lord Emsworth’s sister Florence. He disliked modern girls. They were jumpy. They wriggled and giggled. They had no conversation. A long motor journey beside one of them, having to stare at Sergeant Murchison’s back all the way, would test him sorely, and not for the first time he found himself wishing that he had a stronger will or, alternatively, that Brenda had a weaker one. Lord Emsworth, that vague and dreamy peer, would have told him that he knew just how he felt. He, too, was a great sufferer from the tyranny of sisters, of whom he had sufficient to equip half a dozen earls.

It was Brenda who had forced James into politics when a distant relative had left him all that money in her will. He had been at the time a happy young lad-about-town wanting nothing but to remain a happy young lad-about-town, but Brenda was adamant. It is said that there is a woman behind every successful man, and never had the statement been proved more remarkably than in the case of young Jimmy Piper.

Today he thoroughly enjoyed politics and the eminence to which he had risen, and he knew that he would never have done it without her behind him with a spiked stick. Often in the early days he had wanted to give the whole thing up — he could still recall with a shudder what a priceless ass he had felt when making his first appearance before the electors of Pudbury-in-the-Vale — but Brenda would have none of it. He supposed he ought to feel grateful to her, and as a rule he did, but when she suddenly produced girls like rabbits out of a hat, gratitude turned to sullen wrath and he felt justified in snorting with even more vehemence.

Brenda came in as he increased the voltage of his eleventh snort, a formidable figure, formidably dressed. Had she been weaker, she might have shown sympathy for the stricken man, but her deportment and words were those of a strong-minded governess who believed in standing no nonsense from a fractious child.

‘Oh, really, James, must you make such a crisis of it? You are behaving like an aristocrat of the French Revolution waiting for the tumbril. I’d like to be coming with you, but I can’t get away for a day or two. I have that committee meeting.’

If Sir James had been a man of greater mettle, a twelfth snort might have escaped him. As it was, he merely said:

‘Who is this girl I’m taking to the castle?’

‘Surely I told you?’

‘You may have done. I’ve forgotten.’

‘Florence’s stepdaughter Victoria. Florence most unwisely let her come to London to study Art, and she has apparently got involved with an impossible young man. Naturally Florence wants her where she can keep an eye on her.’[1]

She had more to say, but at this point a knock on the door interrupted her. There entered a soberly dressed man who gave the impression of having been carved out of some durable kind of wood by a sculptor who had received his tuition from an inefficient tutor. This was Sergeant E. B. Murchison, the detective appointed by the special branch of Scotland Yard to accompany Sir James wherever he went and see to it that he came to no harm from the terror by night and the arrow that flieth by day. He said:

‘The car is at the door, Sir James.’[2]

Sir James made no reply, and Brenda answered for him with a gracious ‘Thank you, Sergeant’. He withdrew, and Sir James looked after him in a manner most unsuitable towards an honest helper who was prepared, if necessary, to die in his defence.

‘God, how I hate that man,’ he muttered.

It was the sort of remark which called out all the governess in Brenda. Her face, always on the stony side, grew stonier. It was as though Sir James had kicked the furniture or refused to eat his rice pudding.

‘Don’t be childish, James.’

‘Who’s being childish?’

‘You’re being childish. You have no reason whatever to dislike Sergeant Murchison.’

‘Haven’t I? How would you like being followed around wherever you go? How would you enjoy being dogged from morning to night by a man who makes you feel as if you were someone wanted by the police because they think you may be able to assist them in their enquiries? I expect daily, when I take a bath, to find Murchison nestling in the soap dish.’

Miss Piper had no patience with these tantrums.

‘My dear James, a man in your position has to have protection.’

‘Why? What’s he supposed to be protecting me from? Is Blandings Castle the den of the Secret Nine? Is Emsworth a modern Macbeth? Is he going to creep into my room at night with a dagger? And if he does, how can that blasted Murchison protect me? How can he stop anyone assassinating me if he’s snoring his repulsive head off a quarter of a mile away? Or will he be sleeping on the mat outside my door? I don’t know what you’re laughing at,’ said Sir James with hauteur, for Brenda’s face had softened into an amused smile.

‘I was picturing Lord Emsworth as a modern Macbeth.’ Sir James had thought of something else to complain about.

‘Shall I be plunging into the middle of a large party? Public dinners are bad enough, but big country house parties are worse. I always used to hate them, even as a young man.’

‘Of course it won’t be a large party. Just Florence and her sister Diana Phipps. What on earth’s the matter, James?’ said Brenda petulantly, for Sir James had leaped like one of the trout he was so fond of catching. His eyes were gleaming with a strange light and he had to gulp before he could speak.

‘Nothing’s the matter.’

‘You jumped.’

‘You surprised me, saying that Diana Phipps was at Blandings. I thought she lived in East Africa.’

‘You know her?’

‘I used to know her ages ago. Before,’ said Sir James, and he spoke bitterly, ‘she chucked herself away on that ass Rollo[3] Phipps.’

‘I always heard he was very attractive.’

‘If you call looking like a film star attractive. Not a brain in his head. Spent all his time shooting big game. My God!’ said Sir James with sudden alarm, ‘There’s no danger of him being at Blandings?’

‘Not unless he is haunting the castle. He was killed by a lion years ago.’

‘And nobody told me!’

‘Why should anyone tell you?’

‘Because… because I would have liked to extend my sympathy to Diana.’

One of the gifts which go to make up the type of super-women to whom Brenda belonged is th

e ability to read faces. Brenda had it in full measure, especially where her brother was concerned.

‘James!’ Her voice was at its keenest. ‘Were you in love with her?’

It might have been supposed that a man of Sir James’s long experience as a Cabinet minister would have replied ‘I must have notice of that question’, but excitement precluded caution. His mind was in a ferment and had flitted back to the days before he had come into all that money and gone into politics, the days when he had been plain Jimmy Piper, longing to make an impression on lovely Diana Threepwood but always tongue-tied, always elbowed to one side by the fellows with the gift of the gab. It was only later, gradually rising on stepping-stones of his dead self to higher things, that he had acquired the politician’s ability to use a great many words when saying nothing.

‘Of course I was in love with her,’ he replied with defiance. ‘We were all in love with her. And she went and threw herself away on Rollo Phipps.’

‘Well, he’s dead now.’

‘Yes, that’s something.’

‘And she’s at Blandings.’

‘Yes.’

‘And you’re going to Blandings.’

‘Yes.’

‘You’re probably glad of it now.’

‘Yes.’

‘You intend to ask her to marry you?’

‘Yes.’

‘It would be an excellent thing for both of you.’

‘Yes.’

‘But there is one thing I must warn you about. I have never met Diana, but if she is anything like the other Threepwood girls, she abominates weakness.’[4]

‘I’m not weak.’

‘You’re shy, which can quite easily give that impression. So when you propose, don’t stammer and yammer. Be firm. Dominate her. Otherwise she won’t look at you.’

‘I’ll remember.’

‘Mind you do. Those girls abominate weakness.’

‘You said that before.’

‘And I say it again. Look at Florence and her husband.’

‘I always thought Underwood was one of those steel and iron American millionaires.’

‘Her second husband. Underwood died, and she married a man who couldn’t say Bo to a goose.’

‘Very rude of him if he did, unless he knew the goose very well.’

‘That’s why Florence and her husband are separated.’

‘They are, are they?’

‘He’s weak. You wouldn’t think it to look at him, because he’s one of those extraordinary virile men in appearance. If you can imagine a Greek god with a small clipped moustache … You had better be starting, James. You heard Sergeant Murchison say the car was waiting.’

‘Let it wait. You don’t know who else will be at Blandings do you?’

‘No, Florence didn’t say.’

‘I was wondering if Gally would be there.’

‘Who?’

‘Galahad Threepwood.’

‘I sincerely hope not,’ said Brenda.

Like the majority of his sisters, she thoroughly disapproved of Lord Emsworth’s younger brother.

‘Do you see anything of Galahad Threepwood nowadays?’ she asked suspiciously.

‘Haven’t seen him for years. We were great friends in the old days.’

The snort which proceeded from Brenda might not have been a snort of the calibre of those which her brother had emitted, but it was definitely a sniff. The subject of the old days was one normally avoided by both of them— on his part from caution, on hers because the mere thought of those days revolted her. She preferred not to be reminded that there had been a time, before she took charge of him, when James had moved in a most undesirable circle — a member in fact of the Pelican Club[5] to which Galahad Threepwood had belonged.

‘I believe he has a prison record,’ she said.

Sir James hastened to correct this hasty statement.

‘No, he was always given the option of a fine.’

‘You are keeping the car waiting,’ said Brenda coldly.

CHAPTER TWO

JNO ROBINSON’S taxi,[6] which meets all the trains at Market Blandings, drew up with a screeching of brakes at the great door of Blandings Castle, and a dapper little man of the type one automatically associates in one’s mind with white bowler hats and race glasses bumping against the left hip alighted with the agile abandon of a cat on hot bricks. This was Lord Emsworth’s brother Galahad, and he moved briskly at all times because he always felt so well. He was too elderly to be rejoicing in his youth, but he gave the impression of rejoicing in something.

A niece of his had once commented on this.

‘It really is an extraordinary thing,’ she had said, ‘that anyone who has had such a good time as he has can be so frightfully healthy. Everywhere you look you see men leading model lives and pegging out in their prime, but good old Uncle Gally, who apparently never went to bed till he was fifty, is still breezing along as fit and rosy as ever.’

Galahad Threepwood was the only genuinely distinguished member of the family of which Lord Emsworth was the head. Lord Emsworth himself had once won a first prize for pumpkins at the Shropshire Agricultural Show, and his Berkshire sow, Empress of Blandings, had three times been awarded the silver medal for fatness, but you could not say that he had really risen to eminence in the public life of England. But Gally had made a name for himself. There were men in London — bookmakers, skittle sharps, jellied eel sellers on race courses, and men like that—who would not have known whom you were referring to if you had mentioned Einstein, but they all knew Gally. He had been, till that institution passed beyond the veil, a man at whom the old Pelican Club pointed with pride, and had known more policemen by their first names than any man in the metropolis.[7]

After paying and tipping Jno Robinson and enquiring after his wife, family and rheumatism, for in addition to being fit and rosy he had a heart which was not only of gold but in the right place, he made his way to the butler’s pantry, eager after his absence in London to get in touch with Sebastian Beach, for eighteen years the castle’s major domo. He and Beach had been firm friends since, as he put it, they were kids of forty.

Beach welcomed him with respectful fervour and produced port for which after his long train journey he was pining, and for a while all was quiet except for the butler’s bullfinch,[8] crooning meditatively to itself in its cage on the window sill. The sort of port you got in Beach’s pantry if you were as old a friend as Gally was did not immediately encourage conversation, but had to be sipped in reverent silence. Eventually Gaily spoke. Having uttered an enthusiastic ‘Woof!’ in appreciation of the elixir, he said:

‘Well, Beach, let’s have all the news. How’s Clarence?’

‘His lordship is in good health, Mr. Galahad.’

‘And the Empress?’

‘Extremely robust.’

‘Clarence still hanging on her lightest word?’

‘His lordship’s affection has suffered no diminution.’

‘Of course it wouldn’t have. I keep forgetting that it’s only a week since I was here.’[9]

‘Was it agreeable in London, sir?’

‘Not very. Have you ever noticed, Beach, how your views change as the years go by?’[10] There was a time when you had to employ wild horses to drag me from London, and they had to spit on their hands and make a special effort. And now I can’t stand the place. Gone to the dogs since they did away with hansom cabs and spats. Do you realize that not a single leg in London has got a spat on it today?’

‘Very sad, sir.’

‘A tragedy. Except for an occasional binge like the annual dinner of the Loyal Sons of Shropshire, which was what took me up there this time, I have shaken the dust of London from my feet. I shall settle down at Blandings and grow a long white beard. The great thing about Blandings is that it never changes. When you come back to it after a temporary absence, you don’t find they’ve built on a red-brick annexe to the left wing and pulled down a couple of the battlements. A spo

t more of the true and blushful, Beach.’

‘Certainly, Mr. Galahad.’

‘Of course one sees new faces. Pig men come and go. The boy who cleans the knives and boots is not always the same. Dogs die and maids marry. And, arising from that, who was the girl I passed on my way through the hall? She reminded me of someone I knew in the old days who used to dive off roofs into tanks of water. Daredevil Esmeralda she called herself. She subsequently married a man in the hay, corn and feed business. Who is this girl? Blue eyes and brown hair. She’s new to me.’

‘That would be her ladyship’s maid, Marilyn Poole, Mr. Galahad.’

‘Ladyship? What ladyship?’

‘Lady Diana,’[11] sir.’

Galahad, who had started and stiffened at the word ‘ladyship’, drew a relieved breath. He was very fond of his sister Diana, the only one of his many sisters with whom he was on cordial terms. When he had left the castle, it had been a purely male establishment, Lord Emsworth and himself its only occupants; and though he would have preferred it to remain so, if it was only Diana who had muscled in, he had no complaints to make. It might so easily have been Hermione or Dora or Julia or Florence.

‘So Lady Diana’s here, is she?’ he said.

‘Yes, sir. She arrived shortly after Lady Florence.’

Gally’s monocle fell from his eye.

‘You aren’t telling me Florence is here?’ he quavered.

‘Yes, Mr. Galahad. Also her stepdaughter, Miss Victoria Underwood.’

Gaily was a resilient man. His monocle might have become detached from the parent eye at the news that Blandings Castle housed his sister Florence, but this further piece of information did much to restore his customary euphoria. Florence, widow of the wealthy J. B. Underwood, the American millionaire, might be a depressant, but his niece Vicky’s company he always enjoyed.

‘How was she?’ he asked.

‘Her ladyship seemed much as usual.’

‘Not Lady Florence. Vicky.’

‘Somewhat depressed, I thought.’

‘I must cheer her up.’