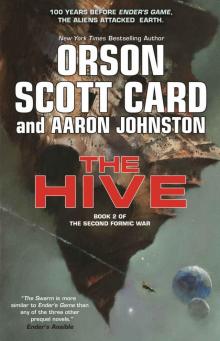

The Hive

Orson Scott Card

Begin Reading

Table of Contents

About the Authors

Copyright Page

Thank you for buying this

Tom Doherty Associates ebook.

To receive special offers, bonus content,

and info on new releases and other great reads,

sign up for our newsletters.

Or visit us online at

us.macmillan.com/newslettersignup

For email updates on Orson Scott Card, click here.

For email updates on Aaron Johnston, click here.

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you without Digital Rights Management software (DRM) applied so that you can enjoy reading it on your personal devices. This e-book is for your personal use only. You may not print or post this e-book, or make this e-book publicly available in any way. You may not copy, reproduce, or upload this e-book, other than to read it on one of your personal devices.

Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the author’s copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

To the men and women

of the United States Armed Forces,

who sacrifice and serve to keep us free.

Deception was the Hive Queen’s greatest weapon. A skilled and experienced architect of war, the Hive Queen, with the help of her distant sisters, devised an invasion strategy for the Second Formic War so unorthodox and alien, so contrary to the established conventions of human warfare, that the International Fleet, despite its years of preparation, was repeatedly deceived, demoralized, and divided.

It began with a swarm of Formic microships sent into our solar system from deep space, so small and slow-moving that they evaded detection as they attached themselves to thousands of our asteroids. Organisms genetically engineered by the Hive Queen then set to work, mining the asteroids for precious metals so that other worms and grubs and microweaving bugs under the Hive Queen’s philotic control could use those harvested minerals to build warships within the hollowed-out centers of these asteroids.

The Hive Queen had not, as the IF had anticipated, brought her fleet with her. Rather, she manufactured it here, right under our noses, using the resources of our own solar system to do so. Then she mobilized these factories of war by moving the asteroids out of their normal orbits and into strategic locations of her choosing. These movements sparked widespread panic within the highest ranks of the IF, as many feared that the enemy would send these asteroids hurtling toward Earth, initiating an extinction event unseen since the dinosaurs.

But the Hive Queen, as before, showed greater military acumen than the International Fleet gave her credit for. Rather than hurl her asteroids at her desired prize, she employed even greater measures of deception by concealing a small number of asteroids from human scans and scopes. Believing that these asteroids had been destroyed, the International Fleet failed to realize that the Hive Queen was bringing these asteroids together to build a superstructure for her and her army. This superstructure, identified later in IF ansible communiques simply as The Hive, proved to be another example of the true reason behind our innumerable losses and near extinction: the brilliant and cunning military mind of the Hive Queen.

—Demosthenes, A History of the Formic Wars, Vol. 3

CHAPTER 1

Commander

To: chin.li21%[email protected]

From: gerhard.dietrich%[email protected]/vgas

Subject: no place for children

* * *

Colonel Li,

It has been brought to my attention that you intend to bring a group of boys between ages twelve and fourteen to GravCamp for training in zero G combat and asteroid-tunnel warfare. I will respectfully remind you that GravCamp, known officially as Variable Gravity Acclimation School, is not a school for children. It is a training facility of the International Fleet for marines. As in, grown men and women. It’s not an orphanage. Or a day care. Or a summer camp. Our facilities are not intended for the amusement of children.

Do not bring these boys here. Our position out near Jupiter puts us a good distance from the fighting in the Belt, but this is a combat zone. And war is no place for a child. The articles of the Geneva Conventions on this subject are clear. I have attached them to this message for your review. You’ll note that special protections were articulated to orphaned children under the age of fifteen. Protocols were adopted to protect children from even helping combatants. You cannot discard international humanitarian law.

Do not board your transport bound for this facility. If you do, you will be denied entry upon arrival. I won’t have a bunch of little boys scurrying around this facility like a swarm of rats. It is an affront to the dignity of men and women in uniform and a dangerous precedent within the IF. I have informed Rear Admiral Tennegard and Admiral Muffanosa of my strong objections.

Signed,

Colonel Gerhard Dietrich

Commanding Officer, VGAS

* * *

They found the captain’s body drifting in his office with a slaser wound through the head and a mist of blood hovering in the air around him. The self-targeting laser weapon was still held loosely in his hand, and the suicide note on the terminal’s display was brief and apologetic. It took the ship’s doctor and officers over an hour to remove the body and document the scene, and by then word had spread throughout the ship and Bingwen had learned every detail.

The ship was a C-class troop transport that had left an International Fleet fuel depot in the outer rim of the Belt five weeks ago. It was bound for GravCamp out near Jupiter—the Fleet’s special-ops training facility in zero G combat and asteroid-tunnel warfare. Bingwen and the other Chinese boys in his squad were the only real anomalous passengers on board. At ages twelve to fourteen, the boys stood out sharply among the 214 marines on board headed for GravCamp. A few marines had made quite a fuss about having a bunch of boys along for the ride, claiming that war was no place for children. But several of the marines on board knew Bingwen’s squad well, having been with them when Bingwen had taken out a hive of Formics inside an asteroid and killed one of the Hive Queen’s daughters. Upon learning that, the hostile marines had shut up, and everyone had left Bingwen and the boys alone.

But now, following the captain’s death, the cargo hold where all the passengers were quartered was abuzz again with heated conversations. Everyone had a different theory on why the captain would take his own life. The prevailing—and unfounded—belief was that the captain had simply “space-cracked,” that the isolation and emptiness of space, compounded by the daily depressing reports on the war coming in via laserline, were too much for the man to handle.

Bingwen didn’t buy that theory. In his sleep capsule that evening, he hacked into the ship’s database and accessed the incident report and autopsy, neither of which put his mind at ease. The medical examiner suggested that the captain had a hidden history of mental illness and perhaps suffered from an untreated case of PTSD stemming from a previous incident in the war. Bingwen’s review of the captain’s service records revealed that he had recently captained a warship in the Belt but had lost his commission after he had failed to aid another warship requesting assistance, resulting in the death of over two hundred crewmen. Based on what Bingwen read, the captain was lucky he hadn’t been court-martialed for violation of Article 87 of the International Fleet Uniform Code of Military Justice, on wartime charges of acts of cowardice. Someone up the chain had given the captain a break and made him the captain of a transport rather than force him to face a tribunal.

Yet even that didn’t sit well with Bingwen. Had the man killed himself out of guilt? Out of shame?

&

nbsp; The following morning Bingwen gathered with the rest of the marines in the main corridor. A funeral march played over the speakers as a few members of the ship’s permanent crew carried the body tube toward the airlock. Once the captain’s remains were secured inside the airlock, one of the officers read a few verses from Christian scripture and offered a prayer. The ship’s former XO, who was now the new captain, signaled for the loadmaster to open the exterior hatch. Bingwen watched as the body tube launched away silently with a burst of escaping air, spinning end over end until it was lost from view.

Slowly, as if not wanting to be the first to leave, the officers solemnly dispersed and returned to their posts. The passenger marines quickly followed suit. Bingwen and the boys in his squad lagged behind, watching the airlock as if they thought the captain might rematerialize.

“Good riddance, I say,” said Chati.

Nak looked horrified. “Have you no respect for the dead? Or your elders? You shame yourself and China.”

The boys, like Bingwen, were all orphans, recruited out of China by Colonel Li during the first war. They had each scored exceptionally high on tests designed to identify strong potential for military command. More impressive still, they had survived Colonel Li’s aggressive combat and psychological training, or as Nak called it: Colonel Li’s Totally Deranged and Borderline Psychotic Military School of Abuse for Orphans.

Chati rolled his eyes. “Spare me the sermon, Nak. This captain was a monster. You all disliked him as much as I did. Cruel to subordinates. Driven by ego. Plus, I hacked the guy’s service records in the database. He was a total coward. Got all kinds of people killed.”

Nak gave him a withering look. “You read his records? Those are private.”

“He’s dead,” said Chati. “What does it matter?”

“You have no respect,” said Nak. “He was a superior officer.”

“Emphasis on was,” said Chati. “He’s spinning with the stars now.”

Bingwen kept quiet.

“Whatever his motivations,” said Micho, “it’s still sad. I feel for the man’s family.”

“He was a total turd muffin,” said Chati. “He exuded self-importance and treated everyone with contempt, criticizing everything the crew did, and yet all the while, he’s the one with the biggest secret sin of all. The guy was a hypocrite and a scoundrel. You don’t see me shedding any tears. I say the Fleet’s better off without him.”

“You marines okay?”

The boys turned around and found Mazer Rackham behind them. It was the first time Bingwen had even seen Mazer in a formal service uniform.

Chati smiled innocently. “We were just paying our final respects.”

“Indeed,” said Mazer, who gave Chati a disapproving look, suggesting that Mazer had heard their conversation. The boys quickly dispersed, but Bingwen stayed behind. Once he and Mazer were alone Bingwen said, “Something bothers me about the captain’s death.”

“Everything bothers me about the captain’s death,” said Mazer. “But I’m listening.”

“The medical examiner’s report. It said the captain was holding the weapon in his right hand when they found him. Autopsy report said the entry wound was on the right side as well. But the captain was left-handed.”

“Do you always notice people’s dominant hands?” Mazer asked.

Bingwen shrugged. “He saluted with his right, shook hands with his right, probably did a whole lot of things with his right hand because of military policy. But he signed every duty roster with his left hand. I watched him do it. And if I’m going to put a weapon to my temple and pull the trigger, I’m going to be very careful and deliberate about how I do it. I’m not going to want to have an unsteady hand and shoot at a poor angle and merely maim myself. I’m going to use the hand I write with, the hand I’m comfortable using. I want my grip to be sure.”

“Your subtext here is that this isn’t a suicide but a homicide. That’s a serious accusation, Bingwen.”

“His note was typed on his terminal,” said Bingwen. “Not handwritten.”

Mazer shrugged. “I never handwrite anything anymore. Paper is dead. As for the captain’s hand use, he probably always fired with his right hand. Even if he was left-handed. His left eye might be his dominant eye, but all tactical formations and fighting positions rely on right-handed shooting. That’s the training he received. Plus he was over forty, so he was probably trained with traditional ballistic weapons at some point in his youth or early in his career. Those rifles eject empty bullet casings to the right side, away from the soldier. If you’re a lefty, you get hot casings ejected in your face or down your back if you hold it against your left shoulder. So you learn to shoot with your right. And keep in mind the first rule of weaponry: Every marine needs to be able to pick up any weapon on the battlefield and use it if necessary. Meaning, the military doesn’t make left-handed rifles. Everyone uses the same rifle. It’s the same reason why lefties during the twentieth century held grenades upside down when they pulled the pin. Military weapons are made for right-handed people.”

“This was a handgun,” said Bingwen. “Not a grenade or a rifle.”

“Doesn’t matter. If you’re a lefty who has trained your right eye to be the dominant shooting eye, you’re not going to change that up when the weapon is smaller. You’re going to maintain whatever firing doctrine the military burned into your brain. That’s the whole purpose of training, so weapon-handling becomes instinctual and second nature. You trained marines in China. Didn’t you ever have a left-handed marine?”

“Sure. We trained with slasers, though. Never ballistics.”

“But you trained left-handed marines to fire right-handed.”

“I just wonder about the psychology of the moment,” said Bingwen. “What would a man in that state of mind do? He’s distraught, he’s standing at a precipice. His life hangs in the balance. What hand would he use?”

“Why are you fixated on this? And more importantly, how did you get your hands on the incident report and the autopsy? Because those are both obviously highly confidential documents that a thirteen-year-old young man who is a mere passenger on this ship would know better than to read.”

“The security on this ship isn’t particularly strong,” said Bingwen.

“Be smart, Bingwen. If someone were to catch you hacking this ship’s databases, CentCom could inflict all kinds of punishments, including ones that might inhibit your training or participation at GravCamp. Or worse.”

“Doesn’t it strike you as odd, though? Did the captain seem like the kind of man who would take his own life?”

“I didn’t know the man. And I don’t pretend to understand suicide or what goes through a person’s mind before they take that irreversible action. The man was universally disliked by his crew. That was obvious. He couldn’t have been oblivious to that. His commission on a transport was a demotion from his previous assignment in the Belt.”

“What do you know about that previous assignment?” said Bingwen.

“I’ve overheard some things,” said Mazer. “It doesn’t sound like his commission ended honorably.”

“It didn’t. It ended catastrophically, with two hundred marines losing their lives. Because of what the records called ‘acts of cowardice’ on the captain’s part.”

“I’m not going to ask how you know that,” said Mazer.

“It doesn’t matter,” said Bingwen. “What does matter is that this guy’s story proves several disturbing truths to me.”

“Namely?”

“First, the incident that resulted in high casualties isn’t something I had ever heard about, meaning the Fleet was keeping it quiet.”

“The Fleet wouldn’t want something like that widely reported,” said Mazer. “Not among fellow marines and not on Earth. The IF is already highly criticized in the press. If the world knew that cowardice had killed two hundred marines, the IF would have a huge public-relations problem. I’m surprised you were even able to learn about

it. I’d think the IF would scrub the man’s records or at the very least classify the report.”

“That file had an extra layer of encryption,” said Bingwen. “Not a smart security stategy, really. That only drew attention to itself.”

“Like I said, you need to tread carefully, Bingwen. Digging around where you shouldn’t be digging is going to get you noticed. And not in a good way.”

“Disturbing fact number two is that rather than burn this guy, they make him the captain of a transport. They give him another command position. You could argue that it’s a less prestigious commission, but it’s a command position all the same. The guy should have been sent packing. But he wasn’t. He was kept in the game.”

“A bad move,” said Mazer. “I agree.”

“More than a bad move,” said Bingwen. “It’s downright imbecilic. Why would the Fleet do that?”

Mazer shrugged. “Maybe he had a friend higher up the chain of command, someone willing to cut him a break, or someone who thought he was unfairly blamed for the incident. Maybe his uncle is a member of the Hegemony Congress. Maybe he had incriminating evidence on the people above him, and they couldn’t risk burning him for fear that he would release it. Could be a hundred different reasons. I don’t think we’ll ever know.”

“But that’s my point,” said Bingwen. “Whatever the reason, it’s a bad one. It’s not one that reflects well on the International Fleet, and it raises all kinds of suspicions.”

“Like that the captain was murdered,” said Mazer.

“You think I’m being ridiculously paranoid,” said Bingwen.

“I think you’re being inquisitive. I think that’s only natural when something like this happens, particularly considering the captain’s less-than-stellar personality and not-so-golden past. You might even begin to believe that people would want him dead.”