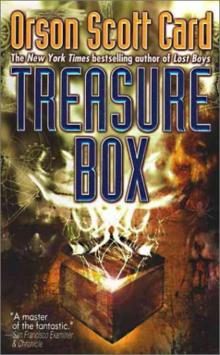

Treasure Box

Orson Scott Card

Treasure Box

Orson Scott Card

Card, Orson Scott

Treasure Box

To Russ and Tammy Card,

dear friends and beloved family,

for the faithfulness that carries you

along roads rough and smooth

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

For the first time in many years, I actually wrote an entire novel at home. Thus every page was wrung from the patience of my family. Kristine and Emily read every chapter as the first draft emerged from the printer, and Geoff was not far behind; the fax lines hummed as Kathy Kidd in remotest Sterling, Virginia, received and read each night's work the morning after. To all four of you, thanks for your responses, which helped me know what I had written and how it needed to be improved.

Later, when the first draft was completed, I had great help from other advance readers, most notably my friend David Fox and my wise editor at Harper, Eamon Dolan; they also have my gratitude. Any flaws still remaining are probably due to my stubborn disregard of good advice.

My thanks to Kathleen Bellamy and Scott Alien for good work under all circumstances. Thanks also to Clark and Kathy Kidd, for giving me DC and northern Virginia.

And last of all my thanks to Charlie Ben and Zina, for reminding me always of the joyful striving of childhood.

1. Harvest

Quentin Fears never told his parents the last thing his sister Lizzy said to him before they pulled the plug on her and let her die.

For three days after the traffic accident, Lizzy lay in a coma, her body hosed, piped, pumped, probed, measured, medicated and fed so the doctors could keep her organs in good condition for transplant, while Mom and Dad struggled with the question of whether she was really dead.

Not that they had any doubts. The doctors showed them the flat lines of Lizzy's brainwaves. The doctors reverently assured the Fearses that if there were the tiniest spark of a hope that Lizzy was actually alive inside that bandaged head, they would cling to that hope and do all in their power to revive her. But there was hope only for the people whose lives might be saved by Lizzy's organs, and then only if they could harvest them before they deteriorated. Mom and Dad nodded, tears streaming down their faces, and believed.

But eleven-year-old Quentin did not believe the doctors. He could see that Lizzy was alive. He could see how the huge bruise reached out from under the bandages, blackening Lizzy's eyes; he watched the bruise change over the three days of the coma, and he knew she was alive. Dead people's bruises didn't change like that. And Lizzy's hands were warm and flexible. Dead people had cold, stiff hands. The machines that measured brainwaves weren't infallible. And who was to say there wasn't something deeper than the electrical activity of the brain?

"Quen understands about brain death," said Dad to one of the doctors late on the first day of her coma. He spoke softly, perhaps thinking Quentin was asleep. "You don't have to talk down to him."

The doctor murmured something even softer. Maybe it began as an apology, but it ended more as a question, a doubt, a demand.

Whatever it was the doctor said, Dad answered, "He and Lizzy were very close."

Quentin murmured his correction: "We are close."

It was just a word. A slip of the tongue. Only it meant that Dad had given up. She was already dead in his mind.

The men moved out into the corridor to continue their conversation. That happened more and more in the hours and days that followed. Quentin knew they were out there plotting how to get him out of the way. He knew that everything any grown-up said to him was bent to that purpose. Grandpa and Grammy Fears came to see him, and then Nanny Say, Mom's mom, but all conversations seemed to come to the same end. "Come on home, dear, and let Lizzy rest."

"Let them murder her, you mean."

And then they'd burst into tears and leave the room and Dad and Mom would come in and there'd be another fight in which Quentin would look them in the eye and say—not screaming, because Lizzy had told him years ago that screaming just made adults think of you as a child and then you'd never get any respect—he would look them in the eye and say whatever would stop them, whatever would make them leave the room with Lizzy still alive on the bed and Quentin still standing guard beside her.

"If you drug me, if you drag me out of here, if you murder her in my sleep, I will hate you for it for the rest of my life. I will never, never, never, never, never..."

"We get the idea," said Dad, his voice like ice.

"Never, never, never, never, never..."

Mom pleaded with him. "Please don't say it, Quen."

"Never forgive you."

This last time the scene played out, on the third day of the coma, Mom rushed crying from the room, out to the corridor where her own mother was already in tears from what Quentin had said to her. Dad was left alone with him in Lizzy's room.

"This isn't about Lizzy anymore," said Dad. "This is about you getting your own way. Well, you're not going to get your own way on this, Quentin Fears, because there's no one on God's green earth who has the power to give it to you. She's dead. You're alive. Your mother and I are alive. We'd like to be able to grieve for our little girl. We'd like to be able to think of her the way she was, not tubed up like this. And while we're at it, we'd like our son back. Lizzy meant a lot to you. Maybe it feels like she meant everything to you and if you let go of her there'll be nothing left. But there is something left. There's your life. And Lizzy wouldn't have wanted you to—"

"Don't tell me what Lizzy would have wanted," said Quentin. "She wanted to be alive, that's what she wanted."

"Do you think your mother and I don't want that too?" Dad's voice barely made a sound and his eyes were wet.

"Everybody wants her dead except for me."

Quentin could see that it took all of Dad's self-control not to hit him, not to rage back at him. Instead Dad left the room, letting the door slam shut behind him. And Quentin was alone with Lizzy.

He wept into her hand, feeling the warmth of it despite the needle dripping some fluid into a vein, despite the tape that held the needle on, despite the coldness of the metal tube of the bedrail against his forehead. "Oh, God," said Quentin. "Oh, God."

He never said that, not the way the other kids did. Oh God when the other team gets a home run. Oh God when somebody says something really stupid. Jesus H. Christ when you bump your head. Quentin wasn't raised that way. His parents never swore, never said God or Jesus except when they were talking religion. And so when Quentin's own mouth formed the words, it couldn't be that he was swearing like his friends. It had to be a prayer. But what was he praying for? Oh God, let her live? Could he even believe in that possibility? Like the Sunday school story, Jesus saying to Jairus, "She isn't dead, the little girl is only sleeping"? Even in the story they laughed him to scorn.

Quentin wasn't Jesus and he knew he wasn't praying for her to rise from the dead. Well, maybe he was but that would be a stupid prayer because it wasn't going to happen. What then? What was he praying for? Understanding? Understanding of what? Quentin understood everything. Mom and Dad had given up, the doctors had given up, everybody but him. Because they all "understood." Well, Quentin didn't want to understand.

Quentin wanted to die. Not die too because he wasn't going to think of Lizzy dying or especially of her already being dead. No, he wanted to die instead. A swap, a trade. Oh God, let me die instead. Put me on this bed and let her go On home with Mom and Dad. Let it be me they give up on. Let it be my plug they pull. Not Lizzy's.

Then like a dream he saw her, remembered her alive. Not the way she looked only a few days ago, fifteen years old, the Saturday morning her friend Kate took her joyriding even though neither of them had a license and Kate spun the car sideways into a tree and a b

ranch came through the open passenger window like the finger of God and poked twenty inches of bark and leaves right through Lizzy's head and Kate sat there completely unharmed except for Lizzy's blood and brains dripping from the leaves onto her shoulder. Quentin didn't see Lizzy with dresses and boys who wanted to take her out and a makeup kit on her side of the bathroom sink. What Quentin saw in his dream of her was the old Lizzy, his best friend Lizzy whose body was as lean as a boy's, Lizzy who was really his brother and his sister, his teacher and his confidante. Lizzy who always understood everything and guided him past the really dumb mistakes of life and made him feel like everything was safe, if you were just smart and careful enough. Lizzy on a skateboard, teaching him how to walk it up the steps onto the porch, "Only don't let Mom see you or she'll have a conniption because she thinks every little thing we do is going to get us killed."

Well it can get you killed, Lizzy. You didn't know everything. You didn't know every damn thing, did you! You didn't know you had to watch out for a twig reaching into the open window of your car and punching a hole in your brain. You stupid! You stupid stupid...

"Mellow out," Lizzy said to him.

He didn't open his eyes. He didn't want to know whether it was Lizzy speaking through those lips, out from under that heavy bandage, or merely Lizzy speaking in the dream.

"I wasn't stupid, it was just the way things happen sometimes. Sometimes there's a twig and there's a car and they're going to intersect and if there's a head in the way, well ain't that too bad."

"Kate shouldn't have been driving without her license."

"Well, aren't you the genius, you think I haven't figured that out by now? What do you imagine I'm doing, lying here in this bed, except going over and over all the moments when I could have said no to Kate? So let me tell you right now, don't you dare blame her, because I could have said no, and she wouldn't have done it. We went joyriding because I wanted to as much as she did and you can bet she feels lousy enough so don't you ever throw it up in her face, do you understand me, you tin-headed quintuplet?"

Quentin didn't want her to tell him off right now. He was in the middle of a war trying to save her life and the last thing he was worried about was Kate. "I'm never going to see her again anyway."

"Well, you should, because if you don't, she's going to think you blame her."

"I don't care what she thinks, Lizzy! All I want is you back, don't you get that?"

"Hey, Tin, there's no way. I'm brain dead. The lights are out. The body's empty. I'm gone. Toast. Wasted."

He didn't want to hear this. "You... are... alive."

"Yeah, well, right, and it's a lot of fun."

"They're trying to kill you, Lizzy. Mom and Dad, just like the doctors. Grammy and Grandpa and Nanny Say, too. They want to unhook you from everything and then cut out your kidneys and your eyes and your heart and your lungs."

"My chitlins, you mean."

"Shut up!"

"My giblets."

"Shut up!" Didn't she know that this wasn't a joke? This was life and death going on here and she was still joking like it didn't matter.

"It does matter," she said. "I'm just trying to cheer you up. Just trying to show you I'm not really gone."

"Well don't tell me, tell them. If I try to tell them you talked to me, they'll put me in the loony bin."

"They're coming to take me away, ha ha, hee hee, ho ho—"

"Stop it!"

"Tin, I'm here, not there, not in that body. Here."

But he wouldn't look up. Didn't want to see whatever she wanted him to see.

"All right, be that way. Stubbornest kid ever spawned of man and woman. You're driving Mom and Dad crazy, you dig, you dig, you dig?"

He did the next step in the ritual. "I dig, I dig, I dig."

"Well, well, well," she said, and giggled.

"They're trying to kill you."

"My body's no good to me anymore, Tin. You know that. And even when it's gone and buried or whatever, I'll still be here."

"Yeah, right, like you're going to come talk to me every day."

"Is that what this is about, then, Tin? What you want? I'm supposed to stay around so you can cuddle me like a stuffed animal or something?"

"Mom and Dad should have been the ones trying to save you!" That was the crux of it, wasn't it? Mom and Dad shouldn't have believed the doctors so easily. Too easily.

"Tin, listen to me. Sometimes your Mom and Dad are the only ones who know when it's time for you to die."

"That's the sickest lousiest most evil thing I ever heard anybody say! Parents don't ever want their children to die!"

"They didn't put the tree there. They didn't put the car there. They didn't put me in the car. They didn't put me in this bed. I did all that myself, Tin, or chance did, or fate or maybe God, he hasn't said. The only choice I left for them was whether my death was going to be completely meaningless or not. Give them a break."

"I'll never forgive them."

"Then I'll never forgive you."

"For what!"

"For keeping me tied down like this, Tin."

He couldn't help it then. He opened his eyes. And she wasn't there. Nobody was there except that still body lying on the bed, breathing into and out of a mask. Her voice was silent.

Quentin got up on rubbery legs and walked to the door. Was it still trembling from his father slamming it? He pulled it open and stepped outside. They were all there, looking at him in surprise: Dad, Mom, Grammy and Grandpa, Nanny Say, and the three main doctors. One of the doctors was holding a hypodermic syringe. Quentin knew what it was for—to tranquilize him so they could get him out of the room. Well, too late. Lizzy had sent him out of the room herself.

"Go ahead and kill her now," said Quentin. Then he turned his back on them and walked down the corridor toward the elevators.

Father came out to the car and talked to him before they harvested Lizzy's organs. In that conversation Quentin broke down and cried and said he was sorry and he knew Mom and Dad weren't killing Lizzy, that she was already dead, and they could go ahead with the organ-taking and he took back what he said about never forgiving them and could he please just wait in the car and not have to talk to grandparents or any of those doctors or nurses, who would be unable to keep the triumph out of their voices or their faces and he couldn't bear it.

"Nobody feels any triumph over this," said Dad.

"No," said Quentin, still trying to say whatever it was Dad needed to hear. "Just relief."

Dad took this in. "Yeah, I guess so, Quen. Relief." Then Dad leaned over and put his arm around him and kissed his head. "I love you, son. I love you for standing by your sister so long. And I love you for stepping away from her in time."

Quentin stayed alone in the car until after his sister's body died. And he never told them that Lizzy had come and talked to him. At first because he was too angry to tell them something so private. And then because he knew they'd put him in therapy to try to get him to understand that it was just a hallucination born of his grief and fear and stress and fatigue. And finally he never said anything because even without therapy he pretty much came to believe that it was, in fact, a hallucination born of grief, fear, stress, and fatigue.

But it was not a hallucination. And deep inside himself, in a place he didn't often go, where he kept the things he didn't like to think about but dared not forget, he knew that Lizzy was still alive somewhere, and somehow she was watching what he did, or at least looking in on him from time to time.

How did he grieve?

He read her library—she always called it that, four shelves on cinderblocks, packed with paperbacks she had bought or been given by friends. He picked up the most-thumbed, most-bent, most-brokenback books and read them first. Lord of the Rings, I Sing the Body Electric, Chronicles of Narnia, Fountainhead, The Crystal Cave, Pride and Prejudice, Rise and Fall of the Third Reich, Stranger in a Strange Land, Gone with the Wind, Childhood's End, Breakfast of Champions, Quentin read them all, an

d yet when he thought back he remembered it differently, remembered hearing them all read aloud to him in Lizzy's voice. Lizzy reading the incantatory cadences of Bradbury, the delicate politeness of Austen; Lizzy telling of the ring slipping accidentally onto Frodo's finger as he fell from a table in Bree; Lizzy reading out the measurements of every male character in Breakfast of Champions and howling with laughter when the narrator declared his own. Lizzy enchanted with Merlin's magic, Lizzy grokking, Lizzy sobbing as she read of a Nazi soldier dashing out a Jewish baby's brains against a wall, Lizzy caught up in the tragic awe of the human children being carried off by the pied piper devil aliens, Lizzy mercilessly ambitious as she built buildings no one else would dare to build or married Frank Kennedy for his money even though he was engaged to her sister. All the voices of all the books were hers. It was the only time Quentin could hear her speaking to him. He read them all and then started over, read each one again and, again, started over.

His parents gave him other books for Christmas, his birthday, as a reward for good grades (Lizzy always had good grades, so Quentin would too). Finally, after Quentin was well started on his fourth passage through those shelves, he came home from school one day and the books were gone.

The shelves were gone. Lizzy's room was gone. Just an empty shell—walls, ceiling, carpet. Only the thumbtack holes in the walls and the red spot in the carpet where she spilled fingernail polish during her one and only attempt at self-decoration remained to prove that she had lived there. Cleaned-out, swept, vacuumed, the room was like her death all over again. For Quentin, perhaps it was really her death for the first time. The silencing of her voice.

He walked into the kitchen where Mom and Dad were sitting at the table. Waiting. They knew what they had done, they knew what it would mean, they were waiting to deal with him together. Quentin walked into the kitchen and got a drink of water and drank it all down and then poured another and emptied it onto the floor.

"Quentin," said Dad, "There's no need to..."