Empire e-1

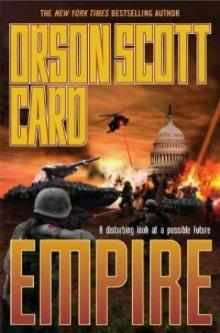

Orson Scott Card

Empire

( Empire - 1 )

Orson Scott Card

Orson Scott Card is a master storyteller, who has earned millions of fans and reams of praise for his previous science fiction and fantasy works. Now he steps a little closer to the present day with this chilling look at a near future scenario of a new American Civil War.

The American Empire has grown too fast, and the fault lines at home are stressed to the breaking point. The war of words between Right and Left has collapsed into a shooting war, though most people just want to be left alone.

The battle rages between the high-technology weapons on one side, and militia foot-soldiers on the other, devastating the cities, and overrunning the countryside. But the vast majority, who only want the killing to stop, and the nation to return to more peaceful days, have technology, weapons and strategic geniuses of their own.

When the American dream shatters into violence, who can hold the people and the government together? And which side will you be on?

Orson Scott Card

Empire

To Cyndie and Jeremy

for finding the balance between the law and the life

and for sharing Victor and Cataan

Captain Malich

Treason only matters when it is committed by trusted men.

The team of four Americans had been in the village for three months. Their mission was to build trust until they could acquire accurate information about the activities of a nearby warlord believed to be harboring some operatives of Al Qaeda.

All four soldiers were highly trained for their Special Ops assignment. Which meant that they understood a great deal about local agriculture and husbandry, trade, food storage, and other issues on which the survival and prosperity of the village depended. They had arrived with rudimentary skills in the pertinent languages, but now they were reasonably fluent in the language of the village.

The village girls were beginning to find occasions to walk near whatever project the American soldiers were working on. But the soldiers ignored them, and by now the parents of these girls knew they were safe enough—though that didn’t stop them from rebuking the girls for their immodesty with men who were, after all, unbelievers and foreigners and dangerous men.

For these American soldiers had also been trained to kill—silently br noisily, close at hand or from a distance, individually or in groups, with weapons or without.

They had killed no one in front of these villagers, and in fact they had killed no one, ever, anywhere. Yet there was something about them, their alertness, the way they moved, that gave warning, the way a tiger gives warning simply by the fluidity of its movement and the alertness of its eyes.

There came a day that one of the villagers, a young man who had been away for a week, came home, and within a few minutes had told his news to the elder who, for lack of anyone better, was regarded by the villagers as the wisest counselor. He, in turn, brought the young man to the Americans.

The terrorists, he said, were building up a cache of weapons away to the southwest. The local warlord had not given his consent—in fact, he disapproved, but would not dare to intervene. “He would be as happy as anyone to be rid of these men. They frighten him as much as they frighten everyone else.”

The young man was also, obviously, afraid.

The Americans got directions from him and strode out of the camp, following one of the trails the shepherds used.

When they were behind the first hill—though this “hill” in most other places would have been called a mountain—they stopped.

“It’s a trap, of course,” said one of the Americans.

“Yes,” said the leader, a young captain named Reuben Malich. “But will they spring it when we reach the place where his directions would send us? Or when we return?”

In other words, as they all understood: Was the village part of the conspiracy or not? If it was, then the trap would be sprung far away.

But if the villagers had not betrayed them (except for the one young man), then in all likelihood the village was in as much danger as the Americans.

Captain Malich briefly discussed the possibilities with his team, so that by the time he gave his orders, they were all in complete agreement.

A few minutes later, using routes they had planned on the first day, before they ever entered the village, they crested the hill at four separate vantage points and spotted the armed men who had just entered the village and were taking up many of the positions surrounding it that the Americans had guessed they would use.

The Americans’ plan, in the event of such an ambush, was to approach these positions with stealth and kill the enemy one by one, silently.

But now Captain Malich saw a scene playing out in the center of the village that he could not bear. For the old man had been brought out into the middle of the sunbaked dirt of the square, and a man with a sword was preparing to behead him.

Captain Malich did the calculations in his head. Protect your own force—that was a prime concern. But if it were the only priority, or the highest priority, nations would keep their armies at home and never commit them to battle at all.

The higher priority here was the mission. If the village sustained any casualties, they would not care that the Americans saved them from even more. They would only grieve that the Americans had ever come at all, bringing such tragedy with them. They would beg the Americans to leave, and hate them if they did not go.

Here were the terrorists, proving that they were, as suspected, operating in the area. This village had been a good choice. Which meant that it would be a terrible waste to lose the trust that had been built up.

Captain Malich took his own weapon and, adjusting wind and distance, took careful aim and killed the swordsman with a single shot.

The other three Americans understood immediately the change of plans. They took aim at the enemies who would be able to take cover most easily, and killed them. Then they settled down to shooting the others one by one.

Of course, the enemy were firing back. Captain Malich himself was hit, but his body armor easily dealt with a weapon fired at such long range. And as the enemy fire slackened, Malich counted the enemy dead and compared it to the number he had seen in the village, moving from building to building. He gave the hand signal that told the rest of his team that he was going in, and they shot at anyone who seemed to be getting into position to kill him as he descended the slope.

In only a few minutes, he was among the small buildings of the village. These walls would not stop bullets, and there were people cowering inside. So he did not expect to do a lot of shooting. This would be knife work.

He was good at knife work. He hadn’t known until now how easy it was to kill another man. The adrenalin coursing through him pushed aside the part of his mind that might be bothered by the killing. All he thought of at this moment was what he needed to do, and what the enemy might do to stop him, and the knife merely released the tension for a moment, until he started looking for the next target.

By now his men were also in the village, doing their own variations on the same work. One of the soldiers encountered a terrorist who was holding a child as a hostage. There was no thought of negotiation. The American took aim instantly, fired, and the terrorist dropped dead with a bullet through his eye.

At the end, the sole surviving terrorist panicked. He ran to the center of the square, where many of the villagers were still cowering, and leveled his automatic weapon to mow them down.

The old man still had one last spring in his ancient legs, and he threw himself onto the automatic weapon as it went off.

Captain Malich was nearest to the terrorist and shot him dead. But the old man had taken a mortal wound. By the time Malich got to him, the old m

an gave one last shudder and died in a puddle of the blood that had poured from his abdomen where the two bullets tore him open.

Reuben Malich knelt over the body and cried out in the keening wail of deep grief, the anguish of a soul on fire. He tore open the shirt of his uniform and struck himself repeatedly on the chest. This was not part of his training. He had never seen anyone do such a thing, in any culture. Striking himself looked to his fellow soldiers like a kind of madness. But the surviving villagers joined him in grief, or watched him in awe.

Within moments he was back on the job, interrogating the abject young betrayer while the other soldiers explained to the villagers that this boy was not the enemy, just a frightened kid who had been coerced and lied to by the terrorists and did not deserve to be killed.

Six hours later, the terrorist base camp was pounded by American bombs; by noon the next day, it had been scoured to the last cave by American soldiers flown in by chopper.

Then they were all pulled out. The operation was a success. The Americans reported that they had suffered no casualties.

“From what one of your men told us,” said the colonel, “we wonder if you might have made your decision to put your own men at risk by firing immediately, based on emotional involvement with the villagers.”

“That’s how I meant it to appear to the villagers,” said Captain Malich. “If we allowed the village to take casualties before we were on the scene, I believe we would have lost their trust.”

“And when you grieved over the body of the village headman?”

“Sir, I had to show him honor in a way they would understand, so that his heroic death became an asset to us instead of a liability.”

“It was all acting?”

“None of it was acting,” said Captain Malich. “All I did was permit it to be seen.”

The colonel turned to the clerk. “All right, shut off the tape.” Then, to Malich: “Good work, Major. You’re on your way to New Jersey.”

Which is how Reuben Malich learned he was a captain no more. As for New Jersey, he had no idea what he would do there, but at least he already spoke the language, and fewer people would be trying to kill him.

Recruitment

When do you first set foot on the ladder to greatness? Or on the slippery slope of treason? Do you know it at the time? Or do you discover it only looking back?

“Everybody compares America to Rome,” said Averell Torrent to the graduate students seated around the table. “But they compare the wrong thing. It’s always, ‘America is going to fall, just like Rome.’ We should be so lucky! Let’s fall just like Rome did—after five hundred years of world domination!” Torrent smiled maliciously.

Major Reuben Malich took a note—in Farsi, as he usually did, so that no one else at the table could understand what he was writing. What he wrote was: America’s purpose is not to dominate anything. We don’t want to be Rome.

Torrent did not wait for note-taking. “The real question is, how can America establish itself so it can endure the way Rome did?”

Torrent looked around the table. He was surrounded by students only a little younger than he was, but there was no doubt of his authority. Not everybody writes a doctoral dissertation that becomes the cover story of all the political and international journals. Only Malich was older than Torrent; only Malich was not confused about the difference between Torrent and God. Then again, only Malich actually believed in God, so the others could be forgiven their confusion of the two.

“The only reason we care about the fall of Rome,” said Torrent, “is because this Latin-speaking village in the heart of the Italian peninsula had forced its culture and language on Gaul and Iberia and Dacia and Britannia, and even after it fell, the lands they conquered clung to as much of that culture as they could. Why? Why was Rome so successful?”

No one offered to speak. So, as usual, Torrent zeroed in on Malich. “Let’s ask Soldier Boy, here. You’re part of America’s legions.”

Reuben refused to let the implied taunting get to him. Be calm in the face of the enemy. If he is an enemy.

“I was hoping you’d answer that one, sir,” said Malich. “Since that’s the topic of the entire course.”

“All the more reason why you should already have thought of some possible answers. Are you telling me you haven’t thought of any?”

Reuben had been thinking of answers to that—and similar questions—ever since he set his sights on a military career, back in seventh grade. But he said nothing, simply regarding Torrent with a steady gaze that showed nothing, not even defiance, and certainly not hostility. In the modern American classroom, a soldier’s battle face was a look of perfect tranquility.

Torrent pressed him. “Rome ruthlessly conquered dozens, hundreds of nations and tribes. Why, then, when Rome fell, did these former enemies cling to Roman culture and claim Roman heritage as their own for a thousand years and more?”

“Time,” said Reuben. “People got used to being under Roman rule.”

“Do you really think time explains it?” asked Torrent scornfully.

“Absolutely,” said Reuben. “Look at China. After a few centuries, most people came to identify themselves so completely with their conquerors that they thought of themselves as Chinese. Same with Islam. Given time enough, with no hope of liberation or revolt, they eventually converted to Islam. They even came to think of themselves as Arabs.”

As usual, when Reuben pressed back, Torrent backed off, not in any obvious, respectful way that admitted Reuben might have scored a point or two, but by simply turning to someone else to ask another question.

The discussion moved on from there into a discussion of the Soviet Union and how eagerly the subject peoples shrugged off the Russian yoke at the first opportunity. But eventually Torrent brought it back to Rome —and to Major Reuben Malich.

“If America fell today, how much of our culture would endure? Most places that speak English in the world do so because of the British Empire, not because of anything America did. What about our civilization will last? T-shirts? Coca-Cola?”

“Pepsi,” joked one of the other students.

“McDonald’s.”

“IPods.”

“Funny, but trivial,” said Torrent. “Soldier Boy, you tell us. What would last?”

“Nothing,” said Reuben immediately. “They respect us now because we have a dangerous military. They adopt our culture because we’re rich. If we were poor and unarmed, they’d peel off American culture like a snake shedding its skin.”

“Yes!” said Torrent. The other students registered as much surprise as Reuben felt, though Reuben did not let it show. Torrent agreed with the soldier?

“That’s why there is no comparison between America and Rome,” said Torrent. “Our empire can’t fall because we aren’t an empire. We have never passed from our republican stage to our imperial one. Right now we buy and sell and, occasionally, bully our way into other countries, but when they thumb their noses at us, we treat them as if they had a right, as if there were some equivalence between our nation and their puny weakness. Can you imagine what Rome would have done if an ‘ally’ treated them the way France and Germany have been treating the United States?”

The class laughed.

Reuben Malich did not laugh. “The fact that we don’t act like Rome is one of the best things about America,” he said.

“So isn’t it ironic,” said Torrent, “that we are vilified as if we were like Rome, precisely because we aren’t? While if we did act like Rome, then they’d treat us with the respect we deserve?”

“My head a-splode,” said one of the wittier students, and everyone laughed again. But Torrent pushed the point.

“ America is at the end of its republic. Just as the Roman Senate and consuls became incapable of ruling their widespread holdings and fighting off their enemies, so America’s antiquated Constitution is a joke. Bureaucrats and courts make most of the decisions, while the press decides which Presidents will

have enough public support to govern. We lurch forward by inertia alone, but if America is to be an enduring polity, it can’t continue this way.”

Even though Torrent’s points actually agreed with much of what Reuben believed was wrong with contemporary America, he could not let the historical point stand unchallenged—the two situations fcould not be compared. “The Roman Republic ended,” said Reuben, “because the people got sick of the endless civil wars among rival warlords.They were grateful to have a strong man like Octavian eliminate all rivals and restore peace. That’s why they were thrilled to have him put on the purple and rename himself as Augustus.”

“Exactly,” said Torrent, leaning across the table and pointing a finger at him. “Of course a soldier sees straight to the crux of the matter. Only a fool thinks the turns of history can be measured by any standard other than which wars were fought, and who won them. Survival of the fittest—that’s the measure of a civilization. And survival is ultimately determined on the battlefield. Where one man kills another, or dies, or runs away. The society whose citizens will stand and fight is the one with the best chance to survive long enough for history even to notice it.”

One of the students made the obligatory comment about how concentrating on war omits most of history. At which Torrent smiled and gestured for Reuben to answer.

“The people who win the wars write the histories,” said Reuben dutifully, wondering why he was getting this sudden burst of respect from Torrent.

“Augustus kept most of the forms of the old system,” Torrent went on. “He refused to call himself king, he pretended the Senate still meant something. So the people loved him for protecting their republican delusions. But what he actually established was an empire so strong that it could survive incompetents and madmen like Nero and Caligula. It was the empire, not the republic, that made Rome the most important enduring polity in history.”