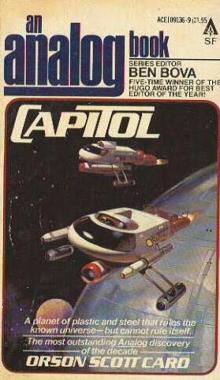

Capitol

Orson Scott Card

Capitol

Orson Scott Card

Orson Scott Card

Capitol

To Jay A. Perry,

Who has read everything and made it better

Preface

Fiction usually does a better job standing on its own, but occasionally a word of explanation can help a reader receive a work as the author means to give it.

Capitol is not a novel; however, it is also not a short story collection. While all the stories in Capitol are completely self-contained, they are placed in the book in chronological order, to gradually unfold the biography of a world and a way of life that is born in "A Steep and a Forgetting" and dies in "The Stars That Blink. " I urge you to read them in order.

Also, Capitol overlaps in time and some characters with Hot Sleep, which is a novel, and which is soon to appear, like Capitol, as an Analog Book. Together, they comprise what is now extant of The Worthing Chronicle.

A SLEEP AND A FORGETTING

There is no remembrance of former things; neither shall there be any remembrance of things that are to come with those that shall come after.

-- Ecclesiastes 1:11

There was nothing remarkable about a rat failing to run a maze. What was remarkable was that five rats ran the maze perfectly-- and five did not.

"My Lord," whispered George Rines.

"Run it again?" asked Vaughn Shirten, the lab assistant who tended the rats.

"Of course."

The five rats who had failed before failed again. The others ran the maze perfectly.

"Vaughn, do you have five rats that have never run a maze at all?"

"Rats of every kind. Smart, stupid, and psychologically virgin." He brought five virgins from the ratroom and put them in their first maze. There was no significant difference between the performance of the virgins and the five rats who had failed to run the maze before.

"My God," whispered George Rines. "What have we done?"

"Made rive smart rats stupid, looks like."

Two days before, all ten rats had run the maze perfectly. They had been divided randomly into two groups. Five of the rats were then given a drug; a day later they were given another. Those were the five that had forgotten how to run the maze.

"I'm not worried about the rats," George said.

"I am," said Vaughn.

"We've been giving that drug to people."

Vaughn looked at him blankly. "People? A stupid drug? Who needs a drug to make people stupid?"

"Somec, Vaughn. Somec."

It was Vaughn's turn to look shocked. "I thought they tested that!"

"All the tests but this one, Vaughn."

"But-- haven't they woken up any of the people who've gone on somec?"

"Not yet." George smiled wanly. "They all had cancer. They didn't want to be wakened until there was a cure."

"Somec." Vaughn laughed. "Some miracle drug!"

"It isn't funny," George said.

* * *

"You signed a contract," Dr. Tell insisted. "You can't publish without my consent."

George shook his head. "I can't publish scholarly papers. So if you won't let me take it to fellow scientists, I'll take it to the press. They'll print the story."

Tell glared; restrained himself from shouting; said, "You bastard. You would."

"It isn't enough just to stop authorizing it. The formula is public knowledge-- what's to stop some grad student from whipping it up in his lab for a friend? Even the life support isn't hard to arrange."

"You don't seem to understand." Slowly, carefully. The smile that had launched a thousand research projects made a struggle to appear on his face. It failed. "There is more at stake than somec."

George closed his eyes.

"There's a thing called independent research. We checked everything. We were so careful, George. We even did rat tests. Gave somec to some rats, not to others, and then taught them both mazes. There was no effect. How were we to know that somec impaired memory?"

"It doesn't impair, Dr. Tell. It eliminates."

"You don't know that."

"I'm pretty damn sure."

"Pretty damn isn't sure enough, George. There's that jackass of a senator who'll stand up and piously denounce federally funded projects that make basket cases out of people who already have problems. He'll do it, you know, and that'll mean funds cut off from everything."

"So what will you do, pretend everything's all right? They're not that far from curing some types of cancer now, and when they can fix it they'll wake up the sleepers who have that cancer and they'll find that they're vegetables."

"I don't know what we're going to do yet!" Dr. Tell shouted.

"We're going to warn the public."

"We're going to keep it quiet until we know what we're going to do."

"And when will that be?"

"I don't know."

George stood up. "I didn't think so. I know, Dr. Tell. It'd be nice to tell the press, there was a disaster, but this is how we're going to solve it in the future. But we can't do that, can we? So we're going to warn people, and warn them now, that somec does exactly what we've claimed it does, with one side effect. It wipes out memory."

"Dammit, George, we don't know that!"

"We suspect it. That's enough."

"If you do this, George, I can promise you that you'll never have a research or teaching job in the United States of America. Or Britain. Or anywhere!"

"In five years there'll be Russian troops all over America and none of us will have teaching jobs except those of us who know what we're doing in a laboratory. No more fund-raising experts, Dr. Tell. So I'm really not worried about your threat."

"And if the Russians don't come, Cassandra?"

"I will have saved some lives."

"'You're out for headlines, you bastard, if it destroys American science in the process! You want to be a crusader! You want to--"

The door slammed, and George didn't hear the rest of the speech. In a way, he knew Dr. Tell was right. George's own first impulse was to keep his discovery silent. He had wrestled with the problem all night, had hardly slept, but he decided at about four a.m. that he really had no choice. Either he could be the crusader who was hated by other scientists, or he could be one of the bastards who hushed it up, hated by the rest of the world. The rest of the world was bigger. And none of the scientists would be left mindless.

He returned to his office to clean out his desk and load his books into boxes. The reporters would be meeting him at his home in three hours. There was no point in pretending to stay at the Institute. His letter of resignation was already on the Director's desk. It was, almost a formality, telling Dr. Tell. But he was the man who was supervising the whole somec project-- he had to know.

I feel like a murderer. So much hope for somec. But is it my fault? No. We were too excited. We thought we had tested everything. We deserve to be punished for acting too quickly, too unthoroughly.

Punished? George frowned at the thought. Not a matter of punishment or guilt or anything. Just stop the somec and find a way to get around the problem.

When he pulled the Scientific Americans off the shelf, they scattered in every direction. There were quite a few of them, most of the recent ones dogeared where he meant to read an article sometime soon. It was the only way he had to keep up on fields other than his own.

Perhaps in order to avoid thinking about the announcement he was going to make to the reporters in a couple of hours, or perhaps because moving out of the office was so distasteful to him, George picked up the top magazine and opened it to the first dog-eared page. He skimmed; read two more articles; then opened another magazine. Braintaping was the title of the first article he turned to; "Instantaneous teaching by establishing currents in the brain

? It may be within reach." It intrigued George enough to lead him into the magazine. And what he found there meant that he wouldn't pack up after all.

It took half an hour to finish the entire article. It took another ten minutes to get in telephone contact with Doran Waite, the man whose name led off the article. And it took three minutes to verify the hope that the article gave.

"Yes, Dr. Rines, that's right. We can't do it with complicated mammals like primates, but with rats we can take the entire learning of one rat and put it into the head of another. For quite a while, they're okay."

"And after a while?"

"They're not okay. They go crazy."

"Dr. Waite, can you come out here? Or better still, can I go out there?"

It took another fifteen minutes to get reservations, and then George left his office without calling home. The reporters could wait until tomorrow. Then he'd have the hopeful note Dr. Tell wanted, the one that could forestall drastic government action, the one that might save the,hundreds of people whose memories were already irrevocably lost.

When it became clear to the reporters who showed up at his house that George Rines was not there and would not be there, they called his office and were told that he had resigned and left. Most gave up then; a few did not; one actually went to the Institute and talked to everyone. No one would talk. Except for the ratman, the lab assistant who cared for the behavioral testing animals. Vaughn Shirten.

The headline was large-- the editor was willing to go with the story when he saw the copy of the press release that the reporter had found on George's desk-- the one he didn't mean to release. It was quoted from extensively, along with a few juicier quotes from Vaughn. "It seems highly likely that at least some of those who have taken somec have been partially or completely deprived of their memory," said George's release. "That means that a hell of a lot of folks won't even know haw to speak or go to the bathroom," Vaughn added helpfully. "It means that they won't have anything left but their instincts. And human beings don't have as much instinct as a planaria."

It was three a.m. in Berkeley when the motel operator finally agreed to call room 215.

"Yes?" George asked sleepily.

"I'm terribly sorry, Mr. Rines. But they insisted that it's an emergency. I told them they just couldn't because we weren't sure that the G. Rines... but there's a government man on the phone, and a U.S. Senator called, and your wife."

"You're kidding," George said. "Let me talk to my wife."

"It is you then? I'm so relieved."

"Yeah, you're fine, let me talk to my--"

"George!" Aggie's voice was anguished. "Oh, George, how could you have just gone off like this--"

"I'm sorry. I didn't think I'd end up staying overnight."

"You might have called!"

"It was after midnight here when I got to the motel. It would have been two a.m. there. I didn't want to wake you up."

"Did you think I could sleep?"

"I'm sorry. Now you know where I am--" he yawned-- "can we go back to sleep?"

"George!" she shouted. "Don't fall asleep! You can't tell me you didn't know there'd be phone calls!"

"About what?"

"Your interview in the paper."

"I didn't do an interview--"

"That's what I told the Senator, but he kept demanding until the reporter found that article and the phone numbers on your desk and called Dr. Waite and--"

"You called Dr. Waite?"

"And he said you had been there all day and George, Dr. Tell called and so did Ron Hubbard and they said you're fired, even though you resigned, and George, there've been phone calls all evening--"

"What senator?"

"Maxwell! The anti-science one that everybody hates so bad. He thinks you're a hero."

"He would, the bastard."

"George, what can I do?"

"Tell them all to wait until I come home. Tve got some things to talk about with Waite."

"George, don't you have any sense of responsibility?"

"I have a sense of being very tired. Tell the reporters that we've already got a solution to a lot of the problem. Tell the Institute they want to see me tomorrow afternoon whether they hate me or not. And tell the senator to go shove a bill up his--"

"George, do you have to be profane?"

"Coarse and vulgar, Aggie, but never profane. It's four a.m. I'll see you tomorrow."

"What if I'm not home when you get there, you rotten--"

He hung up. He had a habit of shutting people out when they were getting abusive. It saved him from a lot of unnecessary anguish. Particularly since they were often correct.

* * *

In two weeks he was no longer a pariah, no longer unemployed. Congress had approved the creation of a research office to solve the somec problem. And George Rines was in charge of it., "Your type of science we need more of," the senator told George. "Courageous. Thinking the new angles."

Raking up the muck, George silently filled in. But he accepted the job and went ahead. It meant a move to California, because Waite and all the equipment were at Berkeley. Aggie and the girls raised hell about it.

"Diane has only another year in high school!" Aggie complained.

"Then stay here," George finally exploded. "It's not as if I needed you out there! I can get twice as much done if I don't have to move the whole family."

He regretted saying it. He apologized. It made no difference. Aggie and Diane and Anita stayed behind, and he had beeen in Berkeley only a week when the notice of their legal separation reached him. He tried to call. He even flew back. But they had moved, too, and left no address except the post office box where he'd better send money every month or find himself in court for abandonment, as the lawyer so carefully put it.

For the entire flight back George was distraught. His world was falling apart. He and Aggie had meant everything to each other for years.

Then he got to Berkeley and never thought about his family except when he got to the motel, and later to the apartment, and realized that there was no one there. Damn them anyway, he thought. Who needs baggage? I'm accomplishing things of lasting value. I'm taking a dangerous drug and making it fulfil its potential for good. And if that doesn't matter as much as the stinking last year in a stupid high school...

* * *

The government money poured in and the research quickly took over an entire building in the new research complex. One department carefully verified the extent of somec damage: when chimps, too, reverted to the behavior of newborn infants despite tremendous amounts of previously learned behavior. The memory loss was total.

Another department continuously played with the braintaping techniques and equipment. One branch of research tried to separate certain kinds of knowledge and memory from others-- it met repeated failures and no success at all. Another branch simplified the method of taping brain patterns and imposing them on another subject. It got to the point where even complex chimpanzee behavior could be taught in three minutes with a taper. The trouble was, the chimpanzees were hopelessly insane within fifteen minutes.

It was the third department that George supervised personally. There somec was mixed with braintaping technology. And there they found the first hopes of success.

The somec story had been front-page news. Now, however, the story was buried; each new success seemed to be timed perfectly to coincide with world events that filled the airwaves and the newspapers.

For example, when George first verified that if a trained rat was braintaped before being drugged with somec, and then the tape was reimpinged on the same, rat's brain after it woke up, the rat immediately regained all its former training, with no measurable impairment at all. And for six weeks afterward there was no sign of insanity. The results were encouraging enough to call a news conference. The reporters came.

But the same day, the president announced that aerial photographs proved that while the missiles had been taken out of Quebec, large concentrations of Russian troo

ps were unloading from the trawlers that were making ridiculously heavy traffic between Leningrad and Montreal. There was only one reason for Russian troops to be in Quebec. "Defense," said the Quebecois PM, during the first interview, before he knew the Russians were going to try to deny it. "Attack," said the U.S. President, and put the troops on alert. "Just try it," said the Russian General Secretary.

The U.S. President didn't, and the somec story was never noticed.

When George found that trained chimps could be taped and their tapes played into other chimps' brains without ill effect provided the receivers had been drugged with somec first, the story was worthy of note, certainly. The reporters thought so, even though the chimps had only been out for a week-- since insanity had always occurred in such a case within an hour, it seemed that the somec had solved the problem. And the Congressional oversight committee authorized George to begin working to try to save the humans who had been put under somec.

However, that news never reached the American public because that week Russian, Polish, Hungarian, and East German troops lurched across the heavily defended border of West Germany and the not particularly heavily defended border of Austria. "Stop," the American President said, "Make us," the General Secretary said. "Use your missiles," cried the Chancellor of West Germany. "We can't be the first to use nuclear weapons," answered the anguished American President. "De Gaulle told you so," the French newspapers, now suddenly Gaullist, cried in print. But no one in Germany read them-- the Russian troops were pouring into Italy, Switzerland, the Netherlands, Denmark by now. And though American troops were dying, the president could not push the button or give the order or even find anyone willing to do it for him. "American promises are a fart in the wind," said the ranking Tory MP, and the Labor PM didn't even deplore the crudity.

George Rines taped the brains of the next of kin of the five healthiest sleepers. They woke up believing they were the other person, but George's staff and the relatives carefully helped the former sleeper realize his true identity and step into that role. Four days after the five humans were awakened, the chimps that had been given another chimp's memories all went crazy. At once. As if on cue.