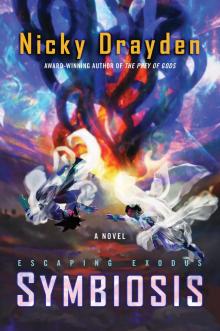

Symbiosis

Nicky Drayden

Dedication

To Dana,

Eternally faithful,

Lover of belly scratches

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Dedication

Content Notes

Interlude: Doka: Of Catching Fish and Releasing Feelings

Part I: Parasitism Seske: Of Desolate Dreams and Fertile Grounds

Doka: Of Collapsed Worlds and Expanded Populations

Seske: Of Fresh Fish and Rotten Eggs

Doka: Of Bloated Chambers and Starving Thrones

Seske: Of High Times and Low Tides

Part II: Commensalism Doka: Of Shallow Roots and Deep Conversations

Seske: Of Upheld Vows and Spilled Milk

Doka: Of Tempting Offers and Disappointing News

Seske: Of Loose Braids and Looser Lips

Doka: Of Familiar Faces and Peculiar Embraces

Part III: Mutualism Seske: Of Closed Hearts and Open Space

Doka: Of Sharp Knives and Dull Testimony

Seske: Of Lively Rescues and Deadly Queens

Doka: Of Trust Falls and Suspicious Behavior

Seske: Of Corrupted Bodies and Just Desserts

Part IV: Surviving Symbiosis Doka: Of Cold Shoulders and Hot Combs

Seske: Of Second Chances and Third Asses

Doka: Of Delicious Recipes and Distasteful Plans

Seske: Of Bright Lights and Dull Echoes

Doka: Of Tainted Air and Bated Breath

Acknowledgments

About the Author

Praise for Escaping Exodus

Also by Nicky Drayden

Copyright

About the Publisher

Content Notes

This story contains depictions of body horror and pregnancy horror (thematic).

Interlude

Doka

Of Catching Fish and Releasing Feelings

My hands throb, pricked with dozens of splinters of my own doing. I am familiar with neither woodworking nor boat making, so I’m counting on a major favor from my ancestors that this vessel I’ve carved won’t sink as soon as I’m on board. I bite back the pain and push the boat out onto the loamy river. The shore is littered with old, half-buried lamps, casting a warm red light that fails to pierce the dense fog lingering along the walls of the cavern. Thoughts echo in my mind as I draw upon non-existent instincts from a single fishing trip my will-mother had taken me on when I was a young boy.

The throttle fish had been plentiful back then, and it took us only twenty silence-filled minutes to catch one—me tossing fistfuls of chum over the side while Mother waited for one of them to swim up a little too close to the boat. She’d reached down and grabbed it with her own two hands but hadn’t smiled when she’d caught it. I’d imagined she’d be proud, but instead, she wiped away a lone tear. It was odd seeing my will-mother lost in her emotions like that. Later that day, when I’d worked up the nerve to question her about her reaction, she claimed the tear to be backsplash from the river.

But reports now indicate that there hasn’t been a throttle fish found in weeks. Nets have been cast, over and over, pulling back nothing but thorny clumps of river weeds. My constituents are breathing down my back, urging me that something needs to be done about it, though they dodge my questions as to why the fish are so important. We’ve got hundreds of them, probably thousands living in the bogs all around our homestead. Won’t those do? I ask them, but they just stare at me, mouths pinched, eyes wide and expectant, acting as though I’m capable of performing miracles just because I’ve poured enough resources into getting the void leaks patched up and have stopped the flooding that was drowning our crops. Well, I don’t have any miracles to offer them, only stubbornness, courage, and hope.

This easily accessible cavern is likely devoid of fish, so I steer my craft toward one of the ducts, getting caught up by the river’s current. I’d made the boat from a piece of discarded gall husk, smooth and rounded on the bottom, just large enough to accommodate me and my fishing equipment. It’s fibrous and rough on the inside, and sharp edges poke through my clothes though I’d done my best to file them down. Of course, I could have taken one of the boats reserved for me, our clan’s matriarch. They’re sleek, comfortable, and probably most important, watertight—but the entire fleet is carved from bone, and I couldn’t stand to look at them, much less navigate one. Nor had I been able to wear the leather gloves that would have protected my hands from getting all chewed up and full of splinters. I’d gone most of my life without wondering where that bone and leather had come from, or at what cost. Now that we know this vast creature in which we’ve built our home has feelings, wants, needs . . . it’s impossible to ignore. I guess some part of me feels that I deserve to suffer in kind.

The boat shifts, tugged along by the flow of the river. I carefully lean to one side and let my arm hang over, drawing a meandering trail in the foam. The black grit sticks to the tips of my fingers, and I roll it back and forth until I’ve got a little ball of putty, shaping it into the likeness of a small worm. I slip it onto my hook and weighted string, and then let it drag behind me, dredging along the bottom of the river, hoping that there’s something swimming down there in the hidden depths, as eager and desperate as I am.

I relax and keep an eye on the bright red buoy tied to my line, trying not to think about the fate of my people resting in these nicked-up hands. In these few short months since our near exodus, I’ve already turned our people’s lives upside-down, taking away their creature comforts, their livelihoods, and much of their way of life in order to stabilize our deteriorating Zenzee. And it’s working. Our efforts are paying off.

But to Seske, my wife—at least for the next few hours—I haven’t gone nearly far enough. I’d given in to her demands at first, stopping the gravitational spin for a while so that our Zenzee could heal, despite the toll null gravity would take on our people. I agreed to tear down homes and businesses to return the bone we’d used as construction material to where we’d stolen it from. But it was never enough for Seske. She wanted to see the whole system burn. After all the hurt she went through, I can’t say I blame her. But still, I walk upon a knife’s edge, knowing if I take a step too far, even my biggest supporters will turn on me, and we could lose everything. So maybe I turn my cheek sometimes, letting our people cling to questionable rituals and outdated traditions in these trying times.

And I think Seske hates me for that.

She’ll be on her way to the Senate chambers soon. Technically, that’s where I should be headed as well, so we can hear the Senate’s decision on whether or not we can annul our marriage without interfering with my title of matriarch. And I would be there right now, if it weren’t for the importance of hunting for throttle fish deep in these eerily quiet bile ducts, all alone and determined to do the impossible for our people.

Maybe it sounds as if I’m running away from my problems, but I’m not.

I swear to the ancestors, I’m not.

Previously explored territory edges into something else as I move downstream. Ley lights strung up from the ceiling of the duct become more spread out, and then they’re gone altogether. The only light now comes from the lamp mounted at the stern of the boat, casting menacing shadows along the walls of the duct.

The fog thickens as I venture deeper. If there’s a chance of there being throttle fish, it’s here in these unexplored branches of the duct. Something knocks against the side of the boat. My heart jumps up into my throat. That was too big of a thump to have been caused by a throttle fish. At least I hope so. Even the small ones back home creep me out—those dour faces with too-human eyes, needle-sharp teeth, and insatiable hunger . . .

Suddenly, this idea of mine seems foolhardy. I shouldn

’t have snuck off like this. It was selfish of me. Our people couldn’t tolerate another change in power right now, another matriarch lost, just as we’re starting to make headway. I need to get back home. So I tie my fishing string on the boat, then grab my oars to press back against the current, which is steadily picking up speed.

Just then, my buoy starts dancing. Something has caught the line. It tugs hard, moving the boat with it. My too-shallow bow dips down and is close to taking on water. Maybe I have some instincts after all, because before I know it, I’ve got a knife in my hand and I cut the line before it can pull me down, too. The whole length of string disappears into the murk below, buoy and all, and the bow pops back up.

I start paddling back in earnest now, but my right oar is yanked from my grip. I barely can process what’s happened before I look over the edge, seeing nothing but a ripple left on the water’s surface.

The boat rocks.

Rocks again.

And again.

Like something is knocking and wants in.

“Hello?” I call out, my warbling voice absorbed by the fleshy walls surrounding me. My ley light starts to flicker. It needs another shake to remix the chemicals inside, but I dare not move toward it. The last thing I need is to offset the balance of this boat.

There is silence. The waters calm. My buoy pops back up from the murky depths, bobbing gleefully as if there’s still something on the line. Not ominous at all, I tell myself. Tales of the deadly creatures that lurk in the bile ducts are just stories told to frighten children into behaving, after all.

Still, I wish I had never come here. I even find myself wishing I were standing before the Senate this very moment, shoulder to shoulder with Seske, ready to hear our fate. It scares me imagining what will come next between us if the annulment goes through, but right now, what’s at the end of that fishing line scares me a little bit more.

And yet, it beckons me.

What if it’s not a hideous monster out to slash my throat and drain me of my life? What if it is a throttle fish? What if this is my chance to prove to my doubters that I am capable of so much more than they expect of me?

I bite my lip, steel my nerves, then use my remaining oar to row the boat slowly toward the buoy. When I’m close enough, I pull it back in. Dangling from the hook is indeed a throttle fish, small . . . not much more than a juvenile. Probably not yet fertile, but it will have to do. A wave of delight washes over me. This proves that they are not all gone. I place it into a jar filled with river water and screw the lid on tight. We will revitalize the rivers from this lone specimen. And as for whatever else is out there . . .

My lost oar floats next to the boat too, now, cracked in half. The claw marks gouged into the wood are unmistakable.

What could have caused it, I have no idea. And I’m pretty sure I’d like to never find out. I paddle harder.

A noise comes from back upstream, like a throaty gargle. I raise my remaining oar up as if it’s a weapon. Like it would be able to protect me from whatever lurks beneath these greasy, gritty waters.

“Weeeeeelllll . . .” The voice comes from beyond the bend, a sustained note, gruff and off-key. “As the river bends, so does my will, we sail the mighty ducts, till the waters doth still. Deep down she goes, and when the waters turn black, kiss your family goodbye, cause there’s no turning back!”

The soft glow of a ley light comes next, and then I see her—Baradonna, my personal security guard, as she steers one of the boats from my fleet, poised and steady, as if she’s been sailing the choppy waters of the bile ducts her whole entire life. The boat gleams, sickle-scaled ivory polished to a high shine, so slick that none of the water’s foam sticks to it. My teeth start to ache, worrying over how our Zenzee had suffered when these sections of bone were stolen from her body. We have worked to mend and replace what we can, but the boat was carved from a solid chunk of bone, now too mutilated and manipulated to salvage and graft it back.

“There you are, my naughty little woodlouse,” Baradonna coos at me, a concerned bend on her brow. She thinks herself to be more of my mother than a guard, like I need another of those. She’s not much older than me, a few years at best, but she wears her hair up in a high crown of elaborate twisted knots and holds her weight like a true matron—a large, stocky build with wide hips, and perfect, pendulous breasts thinly veiled by the sheerness of her uniform. She definitely looks the part of someone formidable enough to serve such an auspicious role.

“Call me Matris Kaleigh. Or Doka, if that’s too hard for you,” I grate at her. We’ve been over this a hundred times. I honestly don’t know why I bother. “And why are you still spying on me? I told you I wanted some privacy.”

She aims her boat at mine, not bothering to slow down or acknowledge my words at all. Our hulls collide with a horrid smack. She latches my boat to hers, then opens her arms, as though she’s expecting an embrace. I fold my arms in response and fix her with my stare.

“No warm welcome for your favorite Baradonna?” she sasses me. “The way I see it, I probably saved your life.”

“Saved my life? I was already returning on my own.”

“Saved your life,” she presses, as if she’s keeping a running tally of the times she’s rescued me from myself. This isn’t the first time. “What possessed you to venture out here all on your own?”

Sighing, I raise the jar, the throttle fish swimming around, aggravated. Little clawed fists knock against the glass. “They said they were extinct in the wild. I’ve proven them wrong.”

“You don’t have to prove anything to them. The environmental researchers should be out here scavenging in these forsaken bile ducts, not you. Why don’t you let them do the work themselves? If they see you going behind them with every aim to prove them wrong, they’re going to start wondering why you created the team in the first place.”

“If they want my trust, then they need to do a more thorough job,” I say, then bite my lip. I’m not sure how much of the blame is the team’s incompetence and how much of it is them quietly rebelling against having a man sitting in the matriarch’s throne. There are so many people who are itching for me to fail, which is why I can’t let simple oversights like these go unchallenged. “I’ll have them all strung up by their thumbs. We’ll see how thorough they are next time.”

“Isn’t that a bit harsh?” Baradonna asks. “I know you’re in a hurry to make a name for yourself, but it can take time to establish rapport. Trust is such a fragile thing. It’s grown and sown, not commanded and demanded.”

She’s right, of course. It was my frustration talking. I take a few deep breaths to calm my nerves. “No thumb hangings,” I say, trying to ignore the fact that I sound like a petulant child. “This time. But they need to know how serious this is. We need to know this Zenzee inside and out. Every crack. Every crevice.”

“Do you want ol’ Baradonna to sweet talk them? You know I can lay on the sap.”

I shake my head. “Just let me borrow an oar.” The least she can do is spare me my dignity and let me row out of here on my own volition.

“I’ll do no such thing,” Baradonna says, reaching for my hand. “Please, Doka, come on over into my boat. Let me row you home.”

“I don’t need you to rescue me,” I huff.

“I think you do,” she says, pointing at my one oar.

“You think just because I’m a man, I can’t figure out how to do this on my own?”

“Nobody is thinking anything like that, especially me. I’m asking to let me rescue you because your boat is taking on water,” she says with one brow cocked. I look down and notice the crack in the hull, water slowly seeping in and forming a pool at the bow. A crack she caused by ramming her boat into mine. I’ve probably got ten minutes left if I’m lucky, not nearly long enough to paddle back upstream with one oar. I look at Baradonna’s sleek, bone-carved craft and frown.

I swallow my misgivings and step over into Baradonna’s boat. She pulls me into her bosom and nea

rly strangles me with her embrace. “I don’t ever want you sneaking off like that again, do you hear me?”

“Yes, ma’am,” I say, my voice muffled by her flesh. The Senate probably thought they were pulling a fast one on me, assigning the most junior Accountancy Guard auditor to watch over my safety, but what Baradonna lacks in experience, she makes up for in heart. And I do feel safer in her presence. Mostly.

“Good,” she says, picking up her paddles, then rowing as though she was bred for it. Broad shoulders, muscled arms, and in a voice only a heart-father could love, she starts singing her rowing tune again. She’s going faster and faster. I bite my lip.

“You can slow down some,” I tell her. “The waters get pretty choppy around this bend. Don’t want to tip us over.”

“The ancestors sit firmly with us. We’ll be fine.”

“You could strain a muscle. Just ease up some, okay?”

“I’m beginning to think that this foolish expedition of yours wasn’t about finding the throttle fish. You’re intentionally trying to miss your annulment proceedings, aren’t you?” Baradonna says, attempting a compassionate smile, but on her, it looks more like hunger.

I am quiet. Baradonna stops paddling. Because she’s right. And she knows that I know she’s right. I don’t even understand why the throttle fish are so important. I needed to get away. The boat comes to a standstill, and silence spreads throughout the bile duct.

“You shouldn’t worry,” she says finally. “I am sure the Senate will decide in your favor. You’ve already proven your worth as Matris, ten times over. The position may have fallen on you when Seske didn’t want it, but you’ve handled it with nothing but grace and intellect. The Senate would be foolish to dismiss you just because Seske wants to throw a tantrum and ignore her responsibilities.”

“Seske’s been through a lot,” I say. “Her sacrifices saved our people. She needs time to think. Time to heal.”