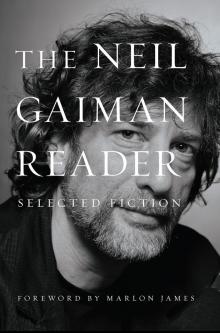

The Neil Gaiman Reader

Neil Gaiman

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Foreword by Marlon James

Preface

We Can Get Them for You Wholesale (1984)

“I, Cthulhu” (1986)

Nicholas Was . . . (1989)

Babycakes (1990)

Chivalry (1992)

Murder Mysteries (1992)

Troll Bridge (1993)

Snow, Glass, Apples (1994)

Only the End of the World Again (1994)

Don’t Ask Jack (1995)

Excerpt from Neverwhere (1996)

The Daughter of Owls (1996)

The Goldfish Pool and Other Stories (1996)

The Price (1997)

Shoggoth’s Old Peculiar (1998)

The Wedding Present (1998)

When We Went to See the End of the World by Dawnie Morningside, age 11¼ (1998)

The Facts in the Case of the Departure of Miss Finch (1998)

Changes (1998)

Excerpt from Stardust (1999)

Harlequin Valentine (1999)

Excerpt from American Gods (2001)

Other People (2001)

Strange Little Girls (2001)

October in the Chair (2002)

Closing Time (2002)

A Study in Emerald (2003)

Bitter Grounds (2003)

The Problem of Susan (2004)

Forbidden Brides of the Faceless Slaves in the Secret House of the Night of Dread Desire (2004)

The Monarch of the Glen (2004)

The Return of the Thin White Duke (2004)

Excerpt from Anansi Boys (2005)

Sunbird (2005)

How to Talk to Girls at Parties (2006)

Feminine Endings (2007)

Orange (2008)

Mythical Creatures (2009)

“The Truth Is a Cave in the Black Mountains . . .” (2010)

The Thing About Cassandra (2010)

The Case of Death and Honey (2011)

The Man Who Forgot Ray Bradbury (2012)

Excerpt from The Ocean at the End of the Lane (2013)

Click-Clack the Rattlebag (2013)

The Sleeper and the Spindle (2013)

A Calendar of Tales (2013)

Nothing O’Clock (2013)

A Lunar Labyrinth (2013)

Down to a Sunless Sea (2013)

How the Marquis Got His Coat Back (2014)

Black Dog (2015)

Monkey and the Lady (2018)

Honors List

Credits

About the Author

Also by Neil Gaiman

Copyright

About the Publisher

Foreword

Thanks to Neil Gaiman, spiders now stop me dead in my tracks. This is a truly weird turn of events, worthy of one of his novels, that now, instead of trying to shoo them away or smash them, I stand frozen, and wonder if this eight-legged brother is about to tell me something that it’s been trying to share since before the slave ships. Something that I’m only now ready to hear. I would explain more, but that would turn this into a foreword for just one novel, Anansi Boys, when this collection is so much more.

Besides, what brought me here was not spiders, but Tori Amos. This already sounds like the line of a ’90s song, and the line I’m writing about is from 1992, and is actually hers: If you need me, me and Neil’ll be hanging out with the Dream King. The lyric clearly means something to Amos and to Gaiman, but it meant something else to a young obsessive of them both. By that time, I had been reading Neil’s work for years. But that one line made me think Amos had done something else. She went into his work and found herself. I remember hearing that song and thinking, “So I’m not the only one who believes in Neil’s world more than my own.”

I still think I live in Gaiman’s world more than my own. For us maladjusted misfits, an escape to his worlds was all that enabled us to endure ours. I would say that Gaiman creates the kind of work that begets obsessions, but that seems too easy. All great art has its devotees, but Gaiman, particularly for other writers and oddballs, regardless of genre or art form, gives us permission to never let go of the world of wonder that we’re all told at some time to leave behind. Of course, the best writers know this is a scam—there is no fantasy world standing opposite the real world, because it’s all real. Not allegory, or fable, but real.

Which might explain why I devoured American Gods when it came out in 2001, a year that badly needed an escape into fantasy. Except that escape was not what it gave me. The novel proposed something way more radical: the idea that the forgotten gods were still around, adjusting quite badly to their twilight, and just because we no longer believed in them didn’t mean that they had stopped messing with us. And it wasn’t just the continued machinations of gods, but the continued importance of myths. After all, a myth was a religion once, and a reality before that, and myths still tell us more about ourselves than religion ever could. Neil Gaiman is a mythmaker, but also a dream restorer. It never even occurred to me that I needed a character to be rescued from simply being relegated to folklore, until he took the stuff of childhood rhymes, half-forgotten, and gave them living, breathing, combative souls. Then he threw them into a present that they weren’t always ready for, and certainly wasn’t ready for them.

This collection abounds in fantastic beasts, normal people with weird powers, weird people with normal struggles, worlds above this one, worlds below, and the real world, which is not as real as you might think. Some stories travel through strange realms in three pages. Some don’t end so much as stop, and some don’t begin so much as pause and wait for you to catch up. Some stories take up an entire city, others a bedroom. Some have the stuff of childhood, with very adult consequences, while others show what happens when grown-up people lose what it means to be a child. And then there are some stories that let you off with a warning, while others leave you so arrested that peeling yourself away from them will take days.

There’s more. Toni Morrison once wrote that Tolstoy could never have known that he was writing for a black girl in Lorraine, Ohio. Neil could never have known that he was writing for a confused Jamaican kid who, without even knowing it, was still staggering from centuries of erasure of his own gods and monsters. Sure, myths were religions once, but they are at the core of a people’s and a nation’s identity. So, when I saw Anansi, on the other side of erasure, responding to being rubbed out and forgotten, I found myself wondering who the hell was this man from the UK who had just restored our story. I understood what being taken away from our myths meant for me, but I had never considered what it meant for the myth.

If Gaiman’s comics and graphic novels turned me into one kind of fan, his fiction turned me into another. I envy the person who, by picking up this collection, will be reading Neil for the first time. But on the other hand, people who know all of the Beatles’ songs still pick up compilations, and they do so for a reason. This is an introduction by way of throwing you in the deep end, touching on nearly everything that has sealed Gaiman’s reputation as one of our masters of fantasy. And yet even for the person who’s read quite a bit of his work, there is still much to discover, even in the old stuff. Like I said, there are people who own every album but still buy the greatest hits, and it’s not because of nostalgia.

It’s that by putting these stories beside each other, a curious new narrative emerges: that of the writer. The excerpt from Neverwhere is brilliant enough on its own but sandwiched between “Don’t Ask Jack” and “The Daughter of Owls,” all three pieces take on a new dimension. Put together, it’s the theme that becomes the story. The secret lives of children, the world of terror and wonder that we leave them to when we turn off the light and close the door. What hap

pens when the door stays closed. What happens when one world moves on and the other does not. It doesn’t escape the reader that “Neverwhere” sounds similar to “Neverland,” another place where a cost is paid when children never grow up. But it does something to you, entering one world still feeling the effects (and bringing the subtext) of the one you have just left behind, taking the fears and wonders of one story to another. Or even better, seeing, as you move through the collection, what keeps Gaiman awake at night.

Other odd things happen in this volume. The way we read certain characters in “I, Cthulhu” shades how we react to their names cropping up several stories later. Those characters never really appear in the second story, but it doesn’t even matter. They have left such a stamp on our imagination that we barely realize that the dread that comes to the latter story is one we bring to it. The subtext of foreboding, the sense that anything could happen is coming from us. This is what great collections do: recontextualize stories, even the ones you’ve read before, and give you brand new ways to read them. Together, they also reveal aspects of story you might not have been aware of when they were apart. Side-splitting humour, for instance. Humour and horror have always been inseparable bedfellows: horror making humour funnier; humour making horror more horrifying. The opening punch of the story “We Can Get Them For You Wholesale” is hilarious not just because of how dark and ridiculous it gets, but because it is punctuated by that most British of qualities, cheapness. Just how far are you willing to go, if there’s a bargain to be had? Spoiler: The end of the world.

Maybe a better comparison for this collection is the Beatles’ ”White Album”: massive in size and scope, with individually brilliant pieces presented together because the only context they need is how good they are. In this volume is funny stuff. Scary stuff. Fantasy stuff. Mystery stuff. Ghost stuff. Kid stuff. Stuff you have read, and much that you haven’t. Stories that reinforce all that you know about Neil Gaiman’s work and stories that will confound what you know. It’s tempting to say that the great thing about this or any storyteller is that he never grew up, but that’s not quite it. In fact, when I was a younger, one of the thrills of Gaiman’s work was how it left me feeling so adult for reading them.

Meaning of course that if you’ve read Neil’s work for as long as I have, then you recognize the rather wicked irony that it took worlds of make believe to make you feel grown up. These characters may have powers, see visions, come from imaginary homelands or do weird, wonderful, sometimes horrible things. But they also come loaded with internal troubles, are riddled with personal conflicts, and sometimes live and die (and come back to life) based on the complicated choices they make. And here I used to think that it was the fairies that were simplistic and the people who were complex.

There’s something so very Christian, or rather Protestant, about the idea of dismissing the imagination as a sign of growing up, and as a diligent student of dead social realist writers, I believed it. But realism is speculation too. And if you were a black nerd like me, a white family from an impossibly clean suburb experiencing nothing more than the drama of crushing ennui as they tear their lives apart just by talking about it was as fantastical as Superman.

Being no fan of H. P. Lovecraft I’ve of course saved him for the end. You can’t talk about a modern fantasist without bring Mr. Mountains of Madness into the room, which is funny given how much he would have hated being in any space with so many others not like him. But when I read Neil Gaiman, I don’t see Lovecraft at all, not even in “I, Cthulhu.” The ghost I see hovering is Borges. Like Jorge Luis, Neil is not writing speculative fiction. He is so given over to these worlds that he has gone beyond speculating about them to living in them. Like Borges, he writes about things as if they have already happened, describes worlds as if we are already living in them, and shares stories as if they are solid truths that he’s just passing along. I don’t think I really believe that in reading great fiction I find myself, so much as I find where I want to be. Because Neil’s stories leave you feeling that his is the world we’ve always lived in, and it’s the “real” world that is the stuff of make-believe.

Marlon James

Preface

The worst conversations, for me, are normally with taxi drivers.

They say, “So what do you do, then?” and I say, “I write things.”

“What kind of things?”

“Um. All sorts,” I say, and I sound unconvincing. I can hear it in my voice.

“Yeah? What sort of stuff is all sorts, then? Fiction, nonfiction, books, TV?”

“Yes. That sort of thing.”

“So, what sort of thing do you write? Fantasy? Mysteries? Science fiction? Literary fiction? Children’s books? Poetry? Reviews? Funny? Scary? What?”

“All of that, really.”

Then the drivers sometimes shoot me a look in the mirror and decide I am taking the mickey, and are quiet, and sometimes they keep going. The next question is always, “Anything I’ve heard of?”

So, then I list the titles of books I’ve written, and all but one of the taxi drivers who have asked the question have nodded, and said they’ve never actually heard of the books, or me, but they will be sure to look them up. Sometimes they ask how to spell my name. (The one taxi driver who pulled over to the side of the road, then got out of the car and then hugged me and had me sign something for his wife was an anomaly, but one that I really liked.)

And I feel awkward for not being somebody who writes one thing—mysteries, say, or ghost stories. Someone who is easy to explain in taxis.

This is a book for all those taxi drivers. But it’s not just for them. It is a book for anybody who, having asked me what I do, and then having asked me what I write, wants to know what book of mine they should read.

Because the answer for me is always, “What kind of things do you like?” And then I try and point them at the thing I’ve written that is closest to what they want to read.

In this book you will find short stories, novelettes and novellas, and even some extracts from novels. (You won’t find any comics or criticism, nor will you find essays, screenplays or poetry.)

The stories, short and long, are in here because I’m proud of them, and you can dip into them and dip out again. They cover all kinds of genres and subjects, and mostly what they have in common is that I wrote them. The other thing they have in common is they were chosen by readers on the Internet, when we asked people to vote for the stories they liked best. This meant that I didn’t have to try and choose favorites. I let the votes for individual stories be our guide to what went in here, and I didn’t put my thumb on the scales to add or lose any stories, except for one. It’s a fable called “Monkey and the Lady,” and I slipped it into this book because it hasn’t been collected anywhere and has only ever appeared in the book it was written for, Dave McKean’s 2017 anthology The Weight of Words. It’s a story I love, very much, although I could not tell you why.

The extracts from novels were harder to choose, and in these I let myself be guided by my beloved editor, Jennifer Brehl. In my head nothing from a novel stands alone, and thus you cannot take extracts from books out of context—except I remember finding a paperback, as a boy, that must have belonged to my father, called A Book of Wit and Humour, edited by Michael Barsley, which mostly consisted of extracts from novels. I still have it. I fell in love with selected passages that then sent me to seek out books I delight in and take pleasure in rereading to this day, like Stella Gibbons’s glorious novel of dark and dreadful Sussex farmhouse doings, Cold Comfort Farm, or Caryl Brahms and S. J. Simon’s magical Shakespearian comedy No Bed for Bacon. So perhaps someone reading this will decide, on the basis of the pages presented here, that American Gods or Stardust (to take two very different novels that both happen to have me as an author) might be their cup of tea, and worth investigating further. I’d like that.

The stories in this book are printed in order of publication, not in order of how much people loved them, earlies

t stories first. You can see me trying to find out who I am as a writer, trying on other people’s hats and glasses and wondering if they suit me, before, eventually, discovering who I had been all along. I encourage you to browse. To start where it suits you, to read whatever tale you feel like reading at that moment.

I love being a writer.

I love being a writer because I’m allowed to do whatever I want, when I write. There aren’t any rules. There aren’t even any guardrails. I can write funny things and sad things, big stories and small. I can write to make you happy or write to chill your blood. I am certain that I would have been a more commercially successful author if I’d just written a book, that was in most ways like the last book, once a year, but it wouldn’t have been half as much fun.

I’ll be sixty soon. I’ve been writing professionally since I was twenty-two. I hope very much that I have another twenty, perhaps even thirty years of writing left in me; there are so many stories I still want to tell, after all, and it’s starting to feel like, if I just keep going, I may one day have an answer for anyone, even a taxi driver, who wants to know what kind of a writer I am.

I may even find out myself.

If you have been on the road with me all these years, reading these stories and novels as they appeared, thank you. I appreciate it and you. If this is our first encounter, then I hope you find something in these pages that amuses you, distracts you, makes you wonder or makes you think—or that simply makes you want to read on.

Thank you for coming, my reader.

Enjoy yourself.

Neil Gaiman

May 2020

Isle of Skye

We Can Get Them for You Wholesale

1984

PETER PINTER HAD never heard of Aristippus of the Cyrenaics, a lesser-known follower of Socrates who maintained that the avoidance of trouble was the highest attainable good; however, he had lived his uneventful life according to this precept. In all respects except one (an inability to pass up a bargain, and which of us is entirely free from that?), he was a very moderate man. He did not go to extremes. His speech was proper and reserved; he rarely overate; he drank enough to be sociable and no more; he was far from rich and in no wise poor. He liked people and people liked him. Bearing all that in mind, would you expect to find him in a lowlife pub on the seamier side of London’s East End, taking out what is colloquially known as a “contract” on someone he hardly knew? You would not. You would not even expect to find him in the pub.