Angels and Visitations

Neil Gaiman

ANGELS & VISITATIONS

A MISCELLANY

PORTRAIT OF THE AUTHOR BY P. CRAIG RUSSELL

ANGELS & VISITATIONS

A MISCELLANY

BY

NEIL GAIMAN

ILLUSTRATED BY

BILL SIENKIEWICZ + JILL KARLA SCHWARZ

STEVE BISSETTE + CHARLES VESS

P. CRAIG RUSSELL + RANDY BROECKER

MICHAEL ZULLI

DREAMHAVEN

MINNEAPOLIS, MINNESOTA 1993

ANGELS AND VISITATIONS

Copyright © 1993 Neil Gaiman

All rights reserved

Stamping Illustration Copyright © 1993 Randy Broecker

Illustration for “Chivalry” Copyright © 1993 Michael Zulli

Illustration for “Troll Bridge” Copyright © 1993 Charles Vess

Illustration for “Webs” Copyright © 1993 Steve Bissette

Illustration for “Cold Colours” Copyright © 1993 Bill Sienkiewicz

Frontispiece Illustration and Illustration for “Murder Mysteries” Copyright © 1993 P. Craig Russell

Illustration for “The Case of the Four and Twenty Blackbirds” Copyright © 1993 Jill Karla Schwarz

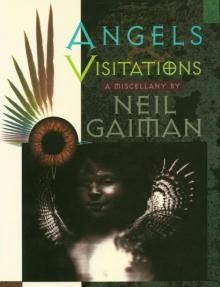

Dustjacket Illustration and Design by David McKean Copyright © 1993 Dave McKean

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

“Introduction” Copyright © 1993 Neil Gaiman. / “The Song of the Audience” Copyright © 1993 Neil Gaiman. / “Chivalry” Copyright © 1992 Neil Gaiman. First appeared in Grails, Quests, Visitations and Other Ocurrences / “Nicholas Was . . .” Copyright © 1989 Neil Gaiman. First appeared in Drabble II-Double Century / “Babycakes” Copyright © 1990 Neil Gaiman. First appeared in Taboo 4 / “Troll Bridge” Copyright © 1993 Neil Gaiman. First appeared in Snow White, Blood Red / “Vampire Sestina” Copyright © 1989 Neil Gaiman. First Published in Fantasy Tales 2 / “Webs” Copyright © 1990 Neil Gaiman. First appeared in More Tales from the Forbidden Planet / “Six to Six” Copyright © 1990 Neil Gaiman. First appeared in Time Out / “A Prologue” Copyright © 1989 Neil Gaiman. First appeared in Soldiers and Scholars / “Foreign Parts” Copyright © 1990 Neil Gaiman. First appeared in Words Without Pictures / “Cold Colours” Copyright © 1990 Neil Gaiman. First appeared in Midnight Graffiti / “Luther’s Villanelle” Copyright © 1989 Neil Gaiman. First appeared in The Adventures of Luther Arkwright 10 / “Mouse” Copyright © 1993 Neil Gaiman. First appeared in Narrow Houses II / “Gumshoe” Copyright © 1989 Punch Publications Ltd. First appeared in Punch / “The Case of the Four and Twenty Blackbirds” Copyright © 1984 Neil Gaiman. First appeared in Knave / “Virus” Copyright © 1990 Neil Gaiman. First appeared in Digital Dreams / “Looking for the Girl” Copyright © 1985 Neil Gaiman. First appeared in Penthouse / “Post-Mortem of our Love” Copyright © 1993 Neil Gaiman. / “Being an Experiment Upon Strictly Scientific Lines” Copyright © 1990 Neil Gaiman. First appeared in 20/20 / “We Can Get Them for You Wholesale” Copyright © 1984 Neil Gaiman. First appeared in Knave / “The Mystery of Father Brown” Copyright © 1991 Neil Gaiman. First appeared in 100 Great Detectives / “Murder Mysteries” Copyright © 1992 Neil Gaiman. First appeared in Midnight Graffiti

First Edition: October 1993

Trade Edition 0–9630944–2-4

Limited Edition 0–9630944–3-2

Published by

DreamHaven Books

1309 Fourth Street S.E.

Minneapolis, Minnesota 55414

Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without prior written permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

CONTENTS

The Song of the Audience

Introduction

Chivalry

Nicholas Was . . .

Babycakes

Troll-Bridge

Vampire Sestina

Webs

Six to Six

A Prologue

Foreign Parts

Cold Colours

Luther’s Villanelle

Mouse

Gumshoe

The Case of the Four and Twenty Blackbirds

Virus

Looking for the Girl

Post-Mortem on Our Love

Being an Experiment Upon Strictly Scientific Lines

We Can Get Them for You Wholesale

The Mystery of Father Brown

Murder Mysteries

ILLUSTRATIONS

AUTHOR PORTRAIT BY P. CRAIG RUSSELL

ILLUSTRATION FOR “CHIVALRY” BY MICHAEL ZULLI

ILLUSTRATION FOR “TROLL-BRIDGE” BY CHARLES VESS

ILLUSTRATION FOR “WEBS” BY STEVE BISSETTE

ILLUSTRATION FOR “SIX TO SIX” BY BILL SIENKIEWICZ

ILLUSTRATION FOR “THE CASE OF THE FOUR AND TWENTY BLACKBIRDS” BY JILL KARLA SCHWARZ

ILLUSTRATION FOR “MURDER MYSTERIES” BY P. CRAIG RUSSELL

DEDICATION.

For my parents, who taught me to read, and gave me the run of the shelves, and who never minded what I read: with affection, and with love, and with gratitude.

THE SONG OF THE AUDIENCE

Let us call now for the makers of strong images,

Let them come to us now carrying their quills and sharp razors

Let them gash their arms for ink and let them limn.

Look at them tracing their desperation, the makers of strong images

Look at their ink clotting brown and black on the parchment skin

Look: they render us down there limb from limb.

Like dreamers they will reduce us in the rendering,

Like ash and fat to soap we are reduced to our essentials

(Like a shadow who stares at us with eyes of flesh).

Let them entertain us, the makers of strong images.

Let us toss them copper pennies. But let us not forget.

They make the images. We give them flesh.

INTRODUCTION

THIS IS not, strictly speaking, a short-story collection, although you’ll find ten short stories in it, stories written over the last ten years. But you’ll find other things too: a few poems, a scrap or two of journalism, an essay, a review.

I’ve spent the last decade writing for a living. I’ve learned my craft as I’ve gone about it—indeed, it sometimes occurs to me that when I began I had little talent, merely the conviction that I was a writer, and enough arrogance and hubris to persist. Much—most—of the shorter prose work I did I am content to see forgotten; this book contains the greater part of what’s left.

Each of these pieces has something in it or about it that made me want to see it preserved in this miscellany. (Incidentally, the OED defines a miscellany as “literary compositions of various kinds, brought together to form a book”.)

I was tempted to rewrite a few of the earlier, clumsier stories, but, in the end, decided not to. It would have been unfair to the author, who was young and sometimes foolish, but had enthusiasm on his side.

I’ve written a few words—in some cases, a very few words—about each of the pieces here, mostly to do with how and why they were written. You may read them now, or you may begin with the first story, where Mrs. Whitaker is already waiting for you.

Chivalry: At the 1991 World Fantasy Convention in Tucson, Ed Kramer asked me for a story for the 1992 World Fantasy Convention souvenir book. He wanted a story with the Holy Grail in it. I told him I’d think about it.

In April 1992, Ed phoned me from the U.S. and told me the deadline was approaching.

I’d been having a bad week. The script I was meant to

be writing just wasn’t happening, and I’d spent days staring at a blank screen, occasionally writing a word like The and staring at it for an hour or so, and then, slowly, letter by letter, I’d delete it and write And or But instead. Then I’d exit without saving.

So Ed phoned and reminded me that I’d promised him a story. And seeing as nothing else was happening, and that this story was living in the back of my mind, I said sure.

I wrote it in a weekend, a gift from the gods, easy and sweet as anything. Suddenly I was a writer transformed: I laughed in the face of danger and spat on the shoes of writer’s block.

Then I sat and stared glumly at a blank screen for another week, because the gods have a sense of humour.

Nicholas Was . . . : Every Christmas I get cards from artists. They paint them themselves, or draw them. They are things of beauty, monuments to inspired creativity.

Every Christmas I feel insignificant and embarrassed and talentless.

So I wrote this one year; wrote it early for Christmas. Dave McKean calligraphed it elegantly and I sent it out to everyone I could think of. My card.

It’s exactly a hundred words long, and first saw print in Drabble II, a collection of hundred-word-long short stories.

And while we’re on the subject, the first joke I remember learning and telling people, as a very small boy, was a riddle. It went:

Q: What do you get if you cross a robin with a vulture?

A: Very depressing Christmas Cards.

I was younger then.

Babycakes: This was written for an anthology that was a benefit for “Creators for the Ethical Treatment of Animals”. It was illustrated by Michael Zulli, who drew the picture of Mrs. Whitaker, and Galaad, and Grizzel the horse, that accompanies my story “Chivalry” in this collection.

It’s a fable of sorts.

Troll Bridge: This was written for Ellen Datlow, for the anthology Snow White, Blood Red, which she edited with Terri Windling. Snow White, Blood Red is an anthology of fairy stories, retold for adults.

I picked The Three Billy Goats Gruff.

Vampire Sestina: This is the only piece of vampire fiction I’ve completed.

John M. “Mike” Ford showed me how to write a sestina. (I owe him thanks not only for that, but also for giving an anagrammatic alternate me the very best song in his delightful novel, How Much For Just The Planet?)

It was published in Fantasy Tales, and reprinted in The Mammoth Book of Vampire Stories, both edited (or co-edited) by Steve Jones, who has edited (or co-edited) more books than anyone else I know, including, with me, a book of nasty poetry for children, called Now We Are Sick (published, coincidentally, by DreamHaven Press).

Hi Steve. Hi Mike.

Webs: This is really a science fiction story, although nobody seems to believe that except me. It’s set a long time from now.

It was published in 1977 in More Tales from the Forbidden Planet, an anthology edited by author and reviewer Roz Kaveney. Rereading it today, for the first time in many years, I noticed odd echoes of Sondheim’s A Little Night Music and Pacific Overtures in there.

Somewhere in my head there’s a huge set of linked short stories that tell the story of Lupita; it begins with two wolves guarding a huge old computer in the snow. “Webs” would be about the third or fourth story in the sequence, set fairly early on in Lupita’s career.

Six to Six: This is all true, except that the garrulous taxi driver at the end wasn’t the one on the way to Victoria, but the one from Gatwick Airport to my house, an hour later.

It was written for Time Out, London’s weekly listings magazine, for a special issue on London’s nightlife.

A Prologue: I met Mary Gentle in 1985, at the Milford SF writers’ workshop, but she had a bad cold; met her again in 1986, and we became friends. She also lived in Croydon, one of the very few cities I know my way around, more or less, and I’d stop by and say hello on my way into London. Sometimes Mary would give me rides back from London to Croydon, and we’d have really good literary arguments in the car. Now I think about it, they were more agreements than arguments. But they were fun.

This was the introduction I wrote for her short-story collection Soldiers and Scholars. I’ve written many introductions over the years, but this was really the only one I felt stood alone, and that I wanted to see reprinted.

Foreign Parts: (I wrote an afterword for this story for Words Without Pictures in 1989. This is a shortened version of that.)

I wrote this story in 1984, and I did the final draft (a hasty coat of paint and some polyfilla in the nastiest cracks) in 1989. In between those two events it sat in a filing cabinet with a number of other short stories, fragments, things—there’s even a children’s book in there somewhere—all of them dusty and most of them well forgotten.

This was written and didn’t sell—the SF editors didn’t like the sex; Penthouse and Knave editors didn’t like the disease. It went into a drawer, only to be pulled out for the Milford SF writers’ conference/workshop in 1985. This wasn’t the story I took with me to the workshop, which was, rightly, and looking back on it, very graciously, ripped to tiny shreds, but we had some extra time on the Saturday after the five days of intensive lit-crit, and needed some extra stories, and, rather diffidently, I showed them all this one.

They liked it. One of them, British author and anthologist Alex Stewart, liked it an awful lot, and when, about a year later, he signed a contract with New English Library to edit Arrows of Eros, an anthology of sex-related SF/Horror stories, he called me and offered it a home.

I said no. Things had changed. In 1984 I had written a story about a venereal disease. The same story seemed to say different things in 1987. The story itself might not have changed, but the landscape around it had altered mightily. I’m talking about AIDS here; and so, whether I had intended it or not, was the story.

If I were going to rewrite the story, I was going to have to take AIDS into account, and I couldn’t. It was too big, too unknown, too hard to get a grip on.

But by 1989 the cultural landscape had shifted once more, shifted to the point where I felt, if not comfortable, then less uncomfortable about taking the story out of the cabinet, brushing it down, wiping the smudges off its face, and sending it out to meet the nice people. So when editor Steve Niles asked if I had anything unpublished for his anthology Words Without Pictures, I gave him this.

I could say that it’s not a story about AIDS. But I’d be lying, at least in part.

On the whole I think it’s mostly about loneliness, and identity, and, perhaps, it’s about the joys of making your own way in the world.

Cold Colours: I’ve worked in a number of different media over the years. Sometimes people ask me how I know what medium an idea belongs to.

Mostly they turn up as comics or films or poems or prose or novels or short stories or whatever. You know what you’re writing ahead of time.

This, on the other hand, was just an idea. I wanted to say something about those infernal machines, computers, and black magic, and something about the London I observed in the late Eighties—a period of financial excess and moral bankruptcy. It didn’t seem to be a short story or a novel, so I tried it as a poem, and it did just fine.

Luther’s Villanelle: This was written as a birthday present for Bryan Talbot.

(Bryan wrote and drew the Adventures of Luther Arkwright comic, which loosely inspired this villanelle.)

The night before Bryan’s birthday, on a signing tour in a hotel in Liverpool, Dave McKean and I made a comic of the poem, repeating panels, or types of panels, where lines repeated. I’ve often wanted to mix formal verse and formal comics. But when it was printed, in a supplement to the comic, two overlays were stuck together, meaning all the lines of verse got tangled up. They’re in the right order here.

Mouse: This was written for Pete Crowther’s anthology Narrow Houses II, an anthology about superstitions. I’d been trying to write him a story about Hollywood, feeding off my experiences in tha

t strange and semi-imaginary place, but found my own dislike of the movie people in my story kept getting in the way—I wasn’t enjoying writing it, and would take any excuse to put it off. Eventually, surfing the deadline, I wrote Pete this.

I’m afraid I actually did hear the radio broadcast mentioned in the text.

Gumshoe: The British magazine Punch was founded in the 1860s and was a source of amusement (to the English) and of bemusement (to foreigners) for over a century.

Punch was a magazine of humorous articles and stories and cartoons. It was a staple of medical waiting rooms across England. It was also “not as good now as it used to be”. This remained true no matter when you began reading or when now was. I’d read Punch sporadically ever since I was a small boy.

I always wanted to write for Punch. I sent the first story I ever wrote to Punch (it began with an angel waking a man up, and telling him that he was now in charge of the universe; I remember that much), and received the first nice-rejection-slip of my career.

Punch closed down in, I believe, 1992. Before it went, I had two pieces published in the magazine, both ostensibly book reviews. This is the second of them; the other had a lot more review in it and seemed a bit out of place here. (It also has the true story of my only time on a police identity line-up.)

I also got to go to a Punch Lunch, a hundred-and-thirty-year-old tradition, where a lunch is eaten around the small table on which all Punch’s editors, major contributors, and Prince Charles have carved their names or initials.

You may have had the kind of nightmare where you turn up at an exam and realise you don’t know anything you’re being tested on. They’re pretty common. This is a fairly true account of what happened to me when something like that actually happened. The style is one I first saw used by Alan Coren, ex-Punch editor and British humorist. It seemed appropriate.