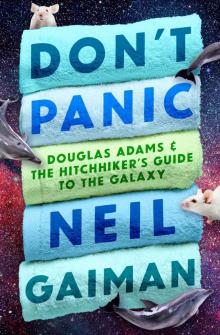

Don't Panic

Neil Gaiman

Don’t Panic

Douglas Adams & The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy

Neil Gaiman

Additional material by David K. Dickson, MJ Simpson, and Guy Adams

CONTENTS

Foreword

Introduction

0 The Hitchhiker’s Guide to Europe

1 DNA

2 Cambridge and Other Recurrent Phenomena

3 The Wilderness Years

4 Gherkin-Swallowing, Walking Backwards and All That

5 When You Hitch Upon a Star

6 Radio, Radio

7 A Slightly Unreliable Producer

8 Have TARDIS, Will Travel

9 H2G2

10 All the Galaxy’s a Stage

11 “Childish, Pointless, Codswalloping Drivel …”

12 Level 42

13 Of Mice, and Men, and Tired TV Producers

14 The Restaurant at the End of the Universe

15 Invasion USA

16 Life, the Universe and Everything

17 Making Movies

18 Liff, and Other Places

19 SLATFAT Fish

20 Do You Know Where Your Towel Is?

21 Games with Computers

22 Letters to Douglas Adams

23 Dirk Gently and Time for Tea

24 Saving the World at No Extra Charge

25 Douglas and Other Animals

26 Anything That Happens, Happens

27 Guides to the Guide

28 The Movies That Don’t Move

29 The Dot.com That Cannot Possibly Go Wrong

30 A Sort of Après-Vie

31 A Hell of a Thing to Climb in a Rhino Costume

32 Shada Redux

33 So, That Would Seem to Have Been That as Far as the Radio Was Concerned

34 Postcards from Daveland

35 Starman

36 The Interconnectedness of All Things

37 Hitchhiking Towards the Future

Appendix I: Hitchhiker’s—the Original Synopsis

Appendix II: The Variant Texts of Hitchhiker’s: What Happens Where and Why

Appendix III: Who’s Who in the Galaxy: Some Comments by Douglas Adams

Appendix IV: The Definitive ‘How to Leave the Planet’

Appendix V: Doctor Who and the Krikkitmen: An Excerpt from the Film Treatment by Douglas Adams

Acknowledgements

About the Author

Because she’s threatened me with consequences too dreadful to consider if I don’t dedicate a book to her …

And because she’s taken to starting every transatlantic conversation with “Have you dedicated a book to me yet?” …

I would like to dedicate this book to intelligent life forms everywhere.

And to my sister, Claire.

FOREWORD

Seventeen years ago a young writer was asked to write a Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy companion. Douglas Adams had agreed some years before that Titan could publish such a book, but the original writer, Richard Hollis, hadn’t written it for reasons I’m still not clear on to this day, and someone at Titan had asked Kim Newman if he wanted to write it. He didn’t—but, he pointed out, he knew someone who had already interviewed Douglas several times.

So Nick Landau, of Titan Books, called me, and asked if I was interested. I wanted to write this book more than anything. I said yes.

Douglas Adams opened his address book to me. I talked to his colleagues, and went through his filing cabinets. I read dozens of scripts and photocopied all of Douglas’s press clippings. I played the Hitchhiker’s computer game to the end, and battled with primitive word processing programs trying to find one that would let me do footnotes. My favourite bits were interviewing Douglas, though, and the way he’d manage to be funny, and serious, and faintly baffled, all at the same time.

You will find many of the great Hitchhiker’s anecdotes in this book (although several of them, such as the tale of the thousands of people blocking the streets for the first Forbidden Planet book signing, had not yet evolved in early 1987 when the greater part of the book was written).

Don’t Panic has been updated and expanded twice.* David K. Dickson wrote chapters 24-26 in 1993, and in 2002 MJ Simpson wrote chapters 27-30, and overhauled the entire text.

When Douglas died I found myself being interviewed, in newspapers and on the radio, Douglas’s favourite medium, being asked to explain who he was and what he did, and why his absence was a tragedy. Perhaps, it occurs to me now, at the end of the day, one of the most magical things about Douglas’s writing, as with that of his literary hero P. G. Wodehouse, was that you knew the person writing was on your side, that he was not laughing at you, but that you were in on the joke.

Back in 1987 Douglas was bemused by the existence of this book, and doubly bemused by its success. What he would make of a world in which we have not only this but MJ Simpson’s not-actually-authorised-but-by-no-means-unauthorised Douglas Adams biography, Hitchhiker, and Nick Webb’s forthcoming actually-officially-authorised biography Wish You Were Here, I hesitate to think.

I wish he were still around. I’d send him an e-mail and ask him. And he’d write back something serious and funny and faintly baffled, all at the same time.

Neil Gaiman

July 8, 2003

Late

* Now, in fact, for a third time, with Guy Adams slightly revising chapter 30, writing chapters 31-37 and updating appendix ii.

INTRODUCTION

The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy is the most remarkable, certainly the most successful book ever to come out of the great publishing companies of Ursa Minor. It is about the size of a paperback book, but looks more like a large pocket calculator, having upon its face over a hundred flat press-buttons and a screen about four inches square, upon which any one of over six million pages can be summoned almost instantly. It comes in a durable plastic cover, upon which the words

DON’T PANIC

are printed in large, friendly letters.

There are no known copies of The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy on this planet at this time.

This is not its story.

It is, however, the story of a book also called, at a very high level of improbability, The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy; of the radio series that started it all; the six-book trilogy it comprises; the computer games, towel, and television series that it, in its turn, has spawned.

To tell the story of the book—and the radio series, and the towel—it is best to tell the story of some of the minds behind it. Foremost among these is an ape-descended human from the planet Earth, although at the time our story starts he no more knows his destiny (which will include international travel, computers, an almost infinite number of lunches, and becoming mindbogglingly rich) than an olive knows how to mix a Pan Galactic Gargle Blaster.

His name is Douglas Adams, he is six foot five inches tall, and he is about to have an idea.

0

THE HITCHHIKER’S GUIDE TO EUROPE

The idea in question bubbled into Douglas Adams’s mind quite spontaneously, in a field in Innsbruck. He later denied any personal memory of it having happened. But it’s the story he told, and, if there can be such a thing, it’s the beginning. If you have to take a flag reading THE STORY STARTS HERE and stick it into the story, then there is no other place to put it.

It was 1971, and the eighteen year-old Douglas Adams was hitch-hiking his way across Europe with a copy of The Hitchhiker’s Guide to Europe that he had stolen (he hadn’t bothered ‘borrowing’ a copy of Europe on $5 a Day; he didn’t have that kind of money).

He was drunk. He was poverty-stricken. He was too poor to afford a room at a youth hostel (the entire story is told at length in his introduction to The Hitchhiker’s Guide to t

he Galaxy: A Trilogy in Four Parts in England, and The Hitchhiker’s Trilogy in the US) and he wound up, at the end of a harrowing day, flat on his back in a field in Innsbruck, staring up at the stars. “Somebody,” he thought, “somebody really ought to write a Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy.”

He forgot about the idea shortly thereafter.

Five years later, while he was struggling to think of a legitimate reason for an alien to visit Earth, the phrase returned to him. The rest is history, and will be told in this book.

The field in Innsbruck has since been transformed into an unremarkable section of autobahn.

“When you’re a student or whatever, and you can’t afford a car, or a plane fare, or even a train fare, all you can do is hope that someone will stop and pick you up.

“At the moment we can’t afford to go to other planets. We don’t have the ships to take us there. There may be other people out there (I don’t have any opinions about Life Out There, I just don’t know) but it’s nice to think that one could, even here and now, be whisked away just by hitchhiking.”

— Douglas Adams, 1984.

1

DNA

Deoxyribonucleic acid, commonly known as DNA, is the fundamental genetic building block for all living creatures. The structure of DNA was discovered and unravelled, along with its significance, in Cambridge, England, in 1952, and announced to the world in March 1953.

This was not the first DNA to appear in Cambridge, however. A year earlier, on 11th March 1952, Douglas Noel Adams was born in a former Victorian workhouse in Cambridge. His mother was a nurse, his father a postgraduate theology student who was training for holy orders, but gave it up when his friends managed to persuade him it was a terrible idea.

His parents moved from Cambridge when he was six months old, and divorced when he was five. At that time, Douglas was considered a little strange, possibly even retarded. He had only just learned to talk and, “I was the only kid who anybody I knew has ever seen actually walk into a lamppost with his eyes wide open. Everybody assumed that there must be something going on inside, because there sure as hell didn’t seem to be anything going on on the outside!”

Douglas was a solitary child; he had few close friends, and one sister, Susan, three years younger than he was.

In September 1959 he started at Brentwood School in Essex, where he stayed until 1970. He said of the school, “We tended to produce a lot of media trendies. Me, Griff Rhys Jones, Noel Edmunds, Simon Bell (who wrote the novelisation for Griff and Mel Smith’s famous non-award-winning movie, Morons from Outer Space; he’s not a megastar yet, but he gives great parties). A lot of the people who designed the Amstrad Computer were at Brentwood, as well. But we had a very major lack of archbishops, prime ministers and generals.”

He was not particularly happy at school, most of his memories having to do with “basically trying to get off games”. Although he was quite good at cricket and swimming he was terrible at football and “diabolically bad at rugby—the first time I ever played it, I broke my own nose on my knee. It’s quite a trick, especially standing up.

“They could never work out at school whether I was terribly clever or terribly stupid. I always had to understand everything fully before I was prepared to say anything.”

He was a tall and gawky child, self-conscious of his height: “My last year at prep school we had to wear short trousers, and I was so absurdly lanky, and looked so ridiculous, that my mother applied for special permission for me to wear long trousers. And they said no, pointing out I was just about to go into the main school. I went to the main school and was allowed to wear long trousers, at which point we discovered they didn’t have any long enough for me. So for the first term I still had to go to school in short trousers.”

His ambitions at that time had more to do with the sciences than the arts: “At the age when most kids wanted to be firemen, I wanted to be a nuclear physicist. I never made it because my arithmetic was too bad—I was good at maths conceptually, but lousy at arithmetic, so I didn’t specialise in the sciences. If I had known what they were, I would have liked to be a software engineer… but they didn’t have them then.”

His hobbies revolved around making model aeroplanes (“I had a big display on top of a chest of drawers at home. There was a large old mirror that stood behind them, and one day the mirror fell forward and crushed the lot of them. I never made a model plane after that, I was upset, distraught for days. It was this mindless blow that fate had dealt me…”), playing the guitar, and reading.

“I didn’t read as much as, looking back, I wish I had done. And not the right things, either. (When I have children I’ll do as much to encourage them to read as possible. You know, like hit them if they don’t.) I read Biggles, and Captain W. E. Johns’s famous science fiction series—I particularly remember a book called Quest for the Perfect Planet, a major influence, that was. There was an author called Eric Leyland, who nobody else ever seems to have heard of. He had a hero called David Flame, who was the James Bond of the ten-year-olds. But when I should have been packing in the old Dickens, I was reading Eric Leyland instead. But there you go—you can’t tell kids, can you?”

Douglas was also an avid reader of Eagle, at that time Britain’s top children’s comic, and home of Dan Dare. Dan Dare, drawn by artist Frank Hampson, was a science fiction strip detailing the battle between jut-jawed space pilot Dare, his comic sidekick Digby, and the evil green Mekon. It was in Eagle that Douglas first saw print. He had two letters published there at the age of eleven, and was paid the (then) enormous sum of ten shillings each for them. The short story shows a certain precocious talent (see here).

Of Alice in Wonderland, often cited as an influence, he said, “I read or rather, had read to me—Alice in Wonderland as a child and I hated it. It really frightened me. Some months ago, I tried to go back to it and read a few pages, and I thought, ‘This is jolly good stuff, but still…’ If it wasn’t for that slightly nightmarish quality that I remember as a kid I’d’ve enjoyed it, but I couldn’t shake that feeling. So although people like to suggest that Carroll was a big influence—using the number 42 and all that—he really was not.”

The first time that Douglas ever thought seriously about writing was at the age of ten: “There was a master at school called Halford. Every Thursday after break we had an hour’s class called composition. We had to write a story. And I was the only person who ever got ten out of ten for a story. I’ve never forgotten that. And the odd thing is, I was talking to someone who was a kid in the same class, and apparently they were all grumbling about how Mr Halford never gave out decent marks for stories. And he told them, ‘I did once. The only person I ever gave ten out of ten to was Douglas Adams.’ He remembers as well.

“I was pleased by that. Whenever I’m stuck on a writer’s block (which is most of the time) and I just sit there, and I can’t think of anything, I think, ‘Ah! But I once did get ten out of ten!’ In a way it gives me more of a boost than having sold a million copies of this or a million of that. I think, ‘I got ten out of ten once…’”

His writing career was not always that successful.

“I don’t know when the first thoughts of writing came, but it was actually quite early on. Rather silly thoughts, really, as there was nothing to suggest that I could actually do it. All of my life I’ve been attracted by the idea of being a writer, but like all writers I don’t so much like writing as having written. I came across some old school literary magazines a couple of years ago, and I went through them to go back and find the stuff I was writing then. But I couldn’t find anything I’d written, which puzzled me until I remembered that each time I meant to try to write something, I’d miss the deadline by two weeks.”

He appeared in school plays, and discovered a love of performing (“I was a slightly strange actor. There tended to be things I could do well and other things I couldn’t begin to do… I couldn’t do dwarves for example; I had a lot of trouble with dwarf parts.”). Th

en, while watching The Frost Report one evening, his ambitions of a life well-spent as a nuclear physicist, eminent surgeon, or professor of English began to evaporate. Douglas’s attention was caught by six foot five inch future Python John Cleese, performing in sketches that were mostly self-written. “I can do that!” thought Douglas, “I’m as tall as he is!”*

In order to become a writer-performer, he had to write. This caused problems: “I used to spend a lot of time in front of a typewriter wondering what to write, tearing up pieces of paper and never actually writing anything.” This not-writing quality was to become a hallmark of Douglas’s later work.

But the die had been cast. Adams abandoned all his daydreams, even those of being a rock star (he was, in fact, a creditable guitarist), and set out to be a writer-performer.

He left school in December 1970, and, on the strength of an essay on the revival of religious poetry (which brought together on one sheet of foolscap Christopher Smart, Gerard Manley Hopkins and John Lennon), he won an exhibition to study English at Cambridge.

And it was important to Douglas that it was Cambridge.

Not just because his father had been to Cambridge, or simply because he had been born there. He wanted to go to Cambridge because it was from a Cambridge University society that the writers and performers of such shows as Beyond the Fringe, That Was the Week That Was, I’m Sorry I’ll Read That Again and, of course, many of the Monty Python’s Flying Circus team had come.

Douglas Adams wanted to join Footlights.