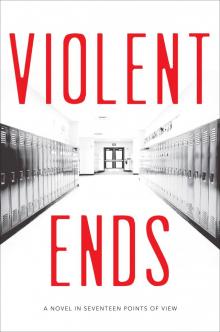

Violent Ends

Neal Shusterman

* * *

Thank you for downloading this eBook.

Find out about free book giveaways, exclusive content, and amazing sweepstakes! Plus get updates on your favorite books, authors, and more when you join the Simon & Schuster Teen mailing list.

CLICK HERE TO LEARN MORE

or visit us online to sign up at

eBookNews.SimonandSchuster.com/teen

* * *

“MISS SUSIE”

Susanna Byrd turned nine that Thursday morning at 7:17 a.m. She kept her eyes on the digital clock on the stove, the spoon of Cream of Wheat with a swirl of clover honey halfway to her mouth, and when it flickered from :16 to :17, she grinned and chomped that spoonful.

Miss Susie had a steamboat.

The steamboat had a bell.

No gifts at breakfast—that’d been the rule forever. But there were three cards under her bowl of Cream of Wheat when she came to the table, and there was her mother, standing behind her chair, smiling.

“Did Dad leave already?”

Mom frowned and nodded, her head cocked at a sympathetic angle. “And Byron, too.”

Susanna’s big brother—the high schooler. He was never around and Susanna didn’t care, anyway.

She’d saved the cards till 7:17, of course, and then she pushed aside her barely eaten bowl of Cream of Wheat with a swirl of clover honey. The top card was from Byron. Susanna tore the envelope (and a little of the card in the process) and scanned his scrawled note that might as well have said, “You suck and I hope you die,” even if it actually said, “Happy birthday, Sis. Love, Byron.”

The next card on the stack was from her grandmother in New York, Susanna’s only living grandparent. That one had a check in it. Susanna adored checks. She pulled it out—it was a pink one—and folded it once and then once again and shoved it into her back pocket.

“Do you want me to bring that to the bank for you today?” Mom asked.

Susanna shook her head. “I wanna go with you. Wait for me to get home.”

The bottom card was from Mom and Dad, with a message from each inside, their handwriting as different as a hammer and a nail.

After breakfast—Susanna ate every last speck of Cream of Wheat with a swirl of clover honey—her mother tied three silver ribbons into her hair, which was the color of buckwheat honey, and she said, “Happy birthday, Susanna. I hope you have a perfect day.”

* * *

It was three blocks south and three blocks east to the bus stop. Susanna would rather walk diagonally, but the streets weren’t made that way. Sometimes she fantasized about soaring like a crow straight from the top of her house to the bus stop, over the other houses and fenced-in yards and other kids. Sometimes she imagined tunneling way down deep, under the basements and sewers and electric cables. Sometimes she just slipped out the front door and waved to her mom and set her eyes on the road ahead till the door closed behind her. Then she skirted the homes and pranced across the grass and cut across backyards and front yards and went diagonally anyway.

Miss Susie went to Heaven

And the steamboat went to Hell—

“I like the ribbons in your hair.” Susanna stopped at the words and let her backpack drop down her arm so the strap settled into her hand. She found Ella standing there, right smack in the middle of a backyard that rightfully shouldn’t have held either of the girls. Ella Stone was the tallest in her grade—but only eight for another six weeks. That gave Susanna seniority.

Ella had hair the color of starflower honey. So rare and desirable.

“Why do you have ribbons in your hair?”

“It’s my birthday,” Susanna said. She didn’t add, “I’m nine.” She hoped Ella would ask.

Ella didn’t.

“Are you going to school today?” Susanna asked.

Ella coughed twice into her elbow—the Dracula; that’s what Susanna’s teachers called it since preschool—and then shook her head. The waves of starflower-honey hair—such a prettier and gentler honey than Susanna’s honey hair—caught the morning sunlight and made Susanna shiver.

“Not ever? You’re skipping school?”

Ella coughed like Dracula again. “I’m going to the doctor. I have pneumonia, Mom says.”

Susanna took a step backward and lifted her bag onto her shoulder again. “Bye.”

-O! operator

Please give me number nine

Susanna crossed Cassowary Lane. She didn’t look both ways. In fact, she closed her eyes as she crossed diagonally through its intersection with Heron Lane, and she listened. She listened and she listened hard, and she didn’t hear a thing. She knew it was safe. The whole time she knew it was safe, but she wasn’t sure she was alive till she felt the grass beneath her feet on the far corner. Then she opened her eyes, and above her a crow croaked and cawed. Susanna had to squint to find it against the sun, still low over the houses of Birdland. It landed at the very top of a fir tree in the nearest backyard.

“I’m nine,” she said to the crow in a quiet, private voice. “Today’s my birthday.”

The crow heard her—she was sure of that. It cocked its head just like Mom.

Crows recognize faces. She saw that on PBS, and PBS only tells the truth. Dad told her that. Susanna couldn’t tell one crow from another, but at least all the crows in Birdland would know her.

She was still looking at the black bird—it shined under the cloudless blue sky, and if its feathers were black (and they were), then its eyes were blacker still, deeper than onyx, deeper than the peak of the night sky if stars didn’t exist—when there came a crack, another crack, and the bird seemed to puff into its own feathers, feathers that fluttered too slowly and fell out of view. The bird was gone.

Susanna dropped her eyes and found three boys. They stood in the backyard two over from that fir tree, and the middle boy—he stood in the center, and was taller than the shorter boy and shorter than the taller boy—held a little rifle. Susanna hurried to the fence and stood there, glaring at them through the chain-link.

“What do you want?” said one—the shortest one. His hair was sandy—barberry honey—and close cut, and his eyes were the color of celery and set far apart. His ears stuck out quite a bit, and the whole package made his face—especially once he grinned, revealing his braces—look like the front view of a family car. He was thirteen, she guessed, because he looked particularly mean, and Susanna set her mind again never to kiss a boy, never to marry one, and never to have babies.

The boy with the gun brought it down from his shoulder and held it by the butt, letting the nozzle bounce along the grass as he walked to the fence. “We shot that bird,” he said. “Are you going to cry about it?”

Susanna shook her head. “Why’d you shoot it?”

“We’re allowed,” the middle boy said. His hair was shaggy and thick, and Susanna imagined putting her fingers in it. She thought they might get stuck. His eyes were like hot chocolate with a single black mini marshmallow in the middle. There’s no such thing as black marshmallows, though. “It’s October. We’re allowed to shoot crows this whole month.”

Susanna didn’t know if this was true. It didn’t seem to make sense that it would be okay to kill a bird in October. Why October? Would it be okay to kill the same bird in November if you shot at it in October and missed? If you went hunting for crows on Halloween, did you have to stop at midnight?

Still, the boy didn’t answer her question, and Susanna didn’t push it. She turned her back on the fence and hitched up her bag and kept on toward the bus stop.

And if you disconnect me

I’ll chop off your behind—

The next street—through two more yards—was Egret Lane, and Susanna stopped again. She was early anyway. Ten more minutes till the

bus would get there, and it usually sat for five at the corner since it was the last pickup before the school. She stopped this time because she found another boy.

He was twelve, and he sat in a front yard, wearing his St. Luke’s school uniform and reading a superhero comic book. Susanna didn’t care for superheroes. Byron did, or he used to. Susanna had no idea what he cared for nowadays, but his disposition in favor of superheroes had turned her off from them forever. Forever and ever, amen.

His hair was no honey color. It was shiny and black and wet or greasy, like the crow that got shot. His eyes were red at the edges and his nose was peppered with freckles. She didn’t have to get close to know those things because he was Kirby Matheson and he lived in that house. The house with a pine tree in the front yard whose lower branches reached wide and close to the ground and made a little hideout beneath them. He said to her when he saw her staring, “What do you want?”

“Nothing,” Susanna said, but she walked across his yard and stooped under the low-hanging pine branches and sat down with him on the bed of brown needles and dirt and sparse grass.

“So get out of here.”

Susanna didn’t, though. She brought her bag around and put it on her lap and said, “It’s my birthday today. I’m nine.”

“Good for you.” He breathed in through his nose and let it out through pursed lips. “Happy birthday.”

“Thank you. Where’s Carah?” That was Kirby’s eleven-year-old sister. She and Kirby were usually outside together in the morning.

“She has a doctor appointment.”

“Is she sick?” Susanna thought about Ella and her pneumonia.

“I don’t know.”

The Mathesons still felt new in Birdland to Susanna because she could remember when they moved in. She couldn’t remember when anyone else in the neighborhood moved in—at least anyone with kids.

“You shouldn’t wear shiny ribbons in your hair and then sit under a tree.”

“Why shouldn’t I?” Susanna reached up and found the end of each ribbon with her fingertips. They were all still there, all still in place.

“You’ll attract crows. They like shiny things.”

“That’s magpies,” Susanna said. “And it’s a myth, anyway.”

“Like you know anything,” said Kirby. “You’re nine.”

Susanna let him sulk a minute and decided to poke at him. She asked, “Were you crying?” It made her feel older for that instant, but also a bit worse. It hurt her heart.

“Get out of here, okay?” Kirby said.

Susanna didn’t. She picked up a pinecone—a dry and brown and open one—and ran her fingers along its teeth. She doubted those flaps of stiff plant matter were really called teeth, but she liked the notion of pine trees dropping hundreds of thousands of brown, sticky teeth. “Did you hear the gunshots?” she asked him, but she didn’t take her eyes off the pinecone.

“Yes.” He grabbed his own pinecone now—Susanna caught him with the corner of her eye—and started pulling the teeth off. “They shot a crow.”

“Did you see it?”

He shook his head. “They do it all the time.”

“Are they in your grade?”

“Yeah. I don’t like those guys, though.”

Susanna watched the bus stop—she could just make it out through the branches and down the block. Kids gathered, most of them with chins down, kicking at curbs, swinging around the stop sign at the corner by one hand, with feet together against the base of the sign like dancers without partners. “They’re mean, right?” Susanna said. “They seem mean to me.”

“I guess,” Kirby said.

Susanna spoke over him. “You look like a crow to me,” she said. “Because you have shiny black hair and black eyes.”

“I have brown eyes.”

“They look black.”

“Because it’s dark under here.”

Susanna leaned forward and squinted at him. “They look black to me.”

“They’re not.”

Susanna tossed her pinecone and pressed her sappy forefinger against her sappy thumb, hard enough and long enough so they stuck for a moment when she pulled them apart, and the skin of both fingers stretched a bit as she did. “You look like a crow.”

“Why are you even here? Go wait for the bus like a normal person.”

Susanna stuck and unstuck her fingers four more times and then grabbed a handful of needles and stood up. She let the needles rain down on his slacks.

“What are you doing?” he snapped, brushing the needles away more violently than necessary. “Get out of here!”

This time, Susanna did.

—the ’frigerator

There was a piece of glass

“Hi, Susanna,” said Henrietta Waters at the bus stop. “Happy birthday.”

“Thanks,” Susanna said, because it was polite and decent to say thanks, but she still thought about Kirby Matheson under his tree and wondered if he’d get up and climb out from under that pine tree to wait for the bus to St. Luke’s, which should be rumbling up Egret Lane any moment now. The boys—the three boys with the rifle—cut across Kirby’s lawn as she watched from the stop sign with one hand on the smooth green stop-sign pole. They didn’t have the rifle anymore. They didn’t see Kirby, either.

“I like your ribbons,” Henrietta said, and Susanna thanked her again. She held on to the pole and let herself swing around it, all the way around—once, twice, three times.

“Did you get any good presents?”

“Not till I get home,” Susanna said, and quickly corrected herself. “Not till my dad gets home from work. But I’m getting a scooter. I think.”

“Ooh, I have a scooter.”

Susanna knew that and she didn’t care, and at that instant she hoped for anything but a scooter. She didn’t like Henrietta Waters, whose hair was nothing like honey as much as Kirby’s hair was nothing like honey, but instead of crow black it was too-bright yellow, like a dandelion head. Dandelion honey was a pretty color, but this wasn’t it. This was sickening.

A silver sedan slid around the corner from Cardinal and slowed as it passed the bus stop. “There goes Ella Stone,” said Henrietta as she gave Susanna a little shove in the arm, meant to get her attention, but rougher.

It was Ella Stone. She sat in the backseat next to the window and looked at her classmates on the curb, coughing into her elbow as they passed.

“She’s dying, you know,” Henrietta said. “My mom told me.”

“No, she’s not.” But Susanna believed her. She even wanted to believe her.

The bus coughed and rumbled up Cardinal Lane and turned wide and rude onto Egret to stop with a hiss for the riders. Susanna watched the pine tree across the street, catching glimpses of it between heads as she moved up the dark, green aisle of the bus. She sat down toward the middle, as usual, next to Andrea Birch, second grader and renowned tattletale. Susanna stretched her neck and looked out the window, and she saw Kirby Matheson, out from his conifer hiding place, and plodding to his bus stop, his shoulders high and his eyelids low, dragging his bag behind him like the dregs of his morning.

Miss Susie sat upon it

And broke her little—

It was a school day like any other for Susanna, inasmuch as a day is like any other when the whole of Mr. Welkin’s third-grade class sings “Happy Birthday” to you and you walk up and down the room passing out erasers with cartoony drawings of frogs and penguins and hippos and unicorns.

“These are dumb.”

Susanna stood next to the Bald Eagle table—they were all named for animals native to the state—and looked down at Simon Loam and his blackberry-honey hair that made her hungry.

“They’re not dumb.”

Simon said it again. “Because those three”—he gestured at the erasers still in her bag—“are real, but this”—he held up his eraser, a unicorn—“is fake-believe.”

“It’s make-believe,” Susanna said. “And if you don’t like it

, put it back.”

“I didn’t say I don’t like it.” He shoved the favor onto the back of his crayon. “I just said it’s dumb.”

Ask me no more questions

I’ll tell you no more lies.

Henrietta Waters wasn’t on the bus home. Neither were two of the boys who shoot birds. One of them was—the tallest one. Susanna didn’t know his name.

None of this was odd. Plenty of kids stayed after school or went home with other kids for playdates in the afternoon. Susanna pulled her book from her bag and flipped through the pages till a chapter title caught her eye—the place where she’d left off or close to it. She didn’t use bookmarks. The sight of a bookmark sticking out from the pages of a book depressed her.

Susanna didn’t walk diagonal from the bus stop to her house. Crossing yards in the afternoon meant dogs off their leashes and parents in kitchens looking out back windows and seeing children not their own traipsing through. They didn’t like that. In the morning they were drowsy and pleased to have their children out of the house, but by late afternoon, with dinner to make, they were grumpy and run-down. So Susanna stuck to the streets, walking with one foot on the grass and the other on the pavement.

When she was half a block from her house, she spotted the black coupe in the driveway beside Mom’s van, and she smiled with her mouth open wide and ran, letting her backpack bounce up and down without a care in the world about how she must have looked to everyone peeking out their front-room windows and the rest of the kids from the bus somewhere behind her.

“Dad!” she shouted as she pushed in through the front door. “You’re home early!”

He stood back from the door, clear across their modest entryway, and crouched with his arms wide. “Here’s the birthday girl.”

She ran to him and smirked at his humph as she collided with his body. She closed her eyes as his arms fell around her.

The boys are in the bathroom

Zipping up their—

Dinner was fish sticks and sweet potato fries with as much ketchup as she could fit on her plate, in spite of Byron’s wailing and moaning on the subject, and in spite of Mom’s head shaking and tongue clucking with every last fart-sounding squirt. Dessert was medovnik—a Czech honey cake of paper-thin layers that took Mom three days to make. Susanna could have melted with every forkful. She could have collapsed to a puddle of honey goo and slid to the dining room floor.