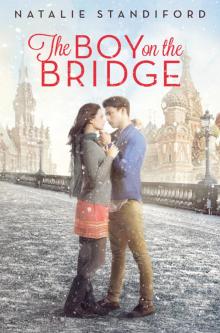

Boy on the Bridge

Natalie Standiford

FOR EDWARDO

CONTENTS

COVER

TITLE PAGE

DEDICATION

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

ALSO BY NATALIE STANDIFORD

COPYRIGHT

JANUARY 1982

Laura and her roommate Karen tramped along the frozen mud road that led through the university, past a wall with OGNEOPASNO! painted on it in huge red letters. An icy wind blew off the Neva River. It was January in Leningrad.

“Flammable,” Karen mumbled, reflexively translating. Somewhere nearby, invisible to the naked eye, there was, apparently, a fire hazard.

“There’s nothing to eat,” Laura complained.

“What are you talking about, comrade?” Karen put on an exaggerated Russian accent. “The Soviet Union produces much food that is tasty. If you don’t like fish head soup or unidentified gray meat, that is your problem. The gristle is the best part! Only four and a half months to go.”

Laura’s laugh was hollow. Two weeks in the Soviet Union and she was already anxious to go home. Five months of bitter cold, inedible food, filthy dorms, boring classes … how would she survive it?

“I wouldn’t mind a little deprivation if everything wasn’t so dull and gray. Where is the passion?” Laura moaned as the wind bit at her nose. “Where is the soul?” All she saw around her was ugliness and a depressing conformity. “Where is the beauty?”

“Is that what you came here for? I came for the wild punk-rock scene. You think you’re disappointed….” Karen stopped just outside the university gate. “I’m going to find a bakery or something. Loaf of black bread?”

“And some cheese, please,” Laura requested.

“If I can find some.”

On their second day in Leningrad, Karen and Laura had walked into a bakery and asked — in their careful classroom Russian — for two rolls. “Can’t you see we’re busy?” the stout woman behind the counter barked. She wore a white apron dusted with flour and a white kerchief in her hair. No one else was in the store except for a skinny, sullen teenage boy who slouched against the empty bread shelves.

“But … we are the only people here,” Laura pointed out.

“Do you have any black bread?” Karen asked.

“We’re busy!” the woman snapped.

Baffled, the two Americans left empty-handed. A few days later, when Laura had stopped in a meat shop to ask for some kolbasa, the butcher replied, “We’re busy! Any idiot can see that!”

Again, she was the only customer in the store, but as she glanced around she realized that they had nothing in stock but a gray pile of ground pork.

“Shoo!” the butcher said. “I’ve got work to do.” He snatched up a penknife and started picking his teeth with it. Laura left.

He was clearly — defiantly — not busy. The real problem seemed to be that he was out of sausage.

Ever hopeful, Karen turned right on her quest for black bread, toward the Palace Bridge, which led to Nevsky Prospekt and the center of the city. Laura turned left, walking down the University Embankment to the Builders’ Bridge that led to Dormitory Number Six. She had to write a paper for Grammar class on “A Typical Day at My American University.”

Leningrad State University dominated Vasilievsky Island, which sat in the middle of the Neva River like an iceberg, dividing it into the Big Neva and the Little Neva. Karen was headed over the Big Neva toward the main part of the city, where most of the major tourist attractions — Nevsky Prospekt, the Hermitage, fancy hotels, other museums and monuments — glittered in the winter sun. Laura prepared to cross the Little Neva to Petrovsky Island, where their dorm — a special dorm for foreigners — stood apart from the main university campus, keeping the foreign students and their bad Western influence safely isolated from the rest of the kids.

At the midpoint of the bridge, when it was too late to turn back, there they were: two gypsy women carrying baby-shaped bundles, their black scarves flapping like crows’ wings, posted like Scylla and Charybdis to assault anyone who tried to pass. There were always at least two gypsy women on the bridge, and they always carried what looked like bundled infants. Laura had yet to see a baby’s face in those bundles, or hear a cry. It struck her as strange that all the gypsy women should have babies exactly the same age, and none older than six months. Where were the gypsy toddlers?

She took a deep breath and charged forward. She had to get across the bridge somehow. It was by far the shortest way back to the dorm, and walking farther than necessary in the bitter cold was not appealing.

“Daitye kopeiki! Daitye! Daitye!” The women swarmed Laura, sweeping the baby bundles under her nose just fast enough so that she couldn’t see inside. “Give us kopecks for the babies!”

At orientation, Laura’s American professor chaperones, the husband-and-wife team of Dr. Stein (wife) and Dr. Durant (husband), had warned the students not to give money to the gypsies, for once you did, they’d never leave you alone. Laura dreaded this confrontation on the bridge every day, twice a day, and even though she suspected that there were no babies — not in those bundles, anyway — she could hardly keep herself from reaching into her pocket for a few thin brown coins. Karen had always stopped her before, but now Karen wasn’t here, and Laura’s resistance was low. If those babies were hungry, she knew how they felt.

She pulled off her gloves and dug into the pockets of her heavy sheepskin coat, but they were empty. She hadn’t brought any money with her. “Forgive me,” she said, struggling to find the Russian words under the stress of the moment. “No money. Nothing.”

The women stood in front of her, blocking her passage across the bridge. Their eyes flashed angrily. By stopping, she’d raised their hopes for a handout, and now they wanted the payoff.

“You have it. Give it to us!”

Laura shook her head emphatically, hoping they’d understand. “I’m sorry. I don’t.” She stepped to the side, and they closed in on her.

“Please!” The English words burst out of her involuntarily. “I’ll bring something next time!”

She pushed past them, not too hard for fear that those bundles might hold real babies after all, and started to run, awkward and bumbling in her bulky coat and boots, slipping on the icy surface of the bridge. The gypsy women chased her, quicker and nimbler than she was. They managed to get in front of her again, waving those swaddled bundles as if they might swat her with them, in a way that definitely suggested there weren’t any babies inside.

“Give it to us!” One woman grabbed at Laura’s book bag, tearing it open and reaching inside. The other stuffed her hands in Laura’s pockets, pulling out a Kleenex and tossing it down in frustration.

“Let me go!” Laura shouted, again in English. She tried to pull away, but they clutched at her coat, holding her back, threatening to topple her onto the ice. Her mind frantically grappled for the right Russian words to make them go away, a magic spell to make the witches disappear.

And then, like magic, the words arrived. Not in her brain, but on the metallic air.

“Stop! Go away. Now!”

A young man ran up from the dorm side of the bridge, shooing the gypsies away as if they were pigeons. They pause

d for a second to stare at him, gauging how dangerous he might be. As if to answer their unspoken question, he added, “Militsia!” The gypsies took off, clutching the bundles to their chests, and disappeared over the arc of the bridge, back toward the university.

“Come on,” the man said to Laura in heavily accented English. He took her hand and together they ran the rest of the way over the bridge, laughing as if they’d just gotten away with something.

On the other side they stopped to catch their breath.

“Thank you,” she said in Russian.

He smiled and bowed his head. “It was nothing,” he said, also in Russian. At her comprehending nod, he added, “You speak Russian?”

“Not perfectly. I’m studying it.”

He tugged his knit cap over his wavy brown hair. On his boyish face — smooth fair skin, rosy cheeks, mischievous brown eyes — sat a short mustache. It looked out of place, almost fake, a contradiction of that tender boyishness. He couldn’t have been much older than she was. Had he grown it in an attempt to look mature, or intimidating? She’d seen a lot of mustaches in Leningrad. Maybe it was a style thing — a Russian style thing that she didn’t get at all.

“Stay away from the gypsies,” he warned her. “They’re thieves. You shouldn’t give them money.”

“That’s what I was told.”

“They’re afraid of the militia. All you have to do is say the word.”

“I’ll remember that.”

“But then, who isn’t afraid of the militia?” He didn’t laugh, but turned up one corner of his mouth — the mustache tilted rakishly — to show that he was joking, sort of. “Where are you from?”

“America.”

His eyes lit up. Everyone’s always did. The word America was also like a magic spell, conjuring a fantasy of cars, clothes, comfort, riches.

“What is your name, girl from America?”

“Laura Reid.”

“Alexei Mikhailovich Nikolayev.” He pulled her still-ungloved hand to his lips and kissed it like a count out of Tolstoy.

Laura laughed nervously. No one had ever kissed her hand before. She couldn’t shake the disoriented feeling that she’d somehow landed in a weird foreign movie. “Hello, Alexei.”

“Hello, Laoora. Call me Alyosha.”

He wore a blue parka with a fur-trimmed hood and, unlike anyone else she’d seen in this frigid January weather, sneakers. A small duffel bag hung from one shoulder, and in his free hand he clutched something wrapped in greasy paper. He held this up to her now. Inside the paper were two small piroshki, meat pies sold by babushkas from carts on the street.

“Are you hungry?” He handed her a small meat pie, wrapped in flaky dough and still warm. “Take this.”

“Thank you.” She bit into it gratefully. It was savory and delicious.

They stood at the foot of the bridge, neither one sure which way to go next. Three streets fanned out in front of them, forks in a road.

“This is where I’m going,” Laura said. Dormitory Number Six loomed, bulky and ugly, straight ahead. Alyosha couldn’t go inside with her. A guard named Ivan was stationed in the lobby, and everyone who entered had to show his or her passport to him.

Alyosha smiled a little sadly. “Okay.”

She took a step toward the dorm, one step, but something made her stop. She couldn’t leave him there. Not yet. Not after he’d rescued her from the gypsies and fed her the most savory meat pie ever baked. She owed him something.

“How can I thank you?” she asked him.

He shrugged. “Take a walk with me?”

There was nothing threatening or dangerous about him, and so far all he’d done was help her. And somehow, even though the afternoon was quickly darkening, she no longer felt cold. Perhaps the meat pie had warmed her bones.

“All right,” she told him.

They walked through the dreary neighborhood beyond her dorm, the streets cluttered with nondescript apartment buildings and shops. A long line formed outside Store Number 47.

Alyosha nodded at the line but showed no interest in joining it. “They must have something good for sale,” he observed. “Maybe cucumbers. Or toilet paper.”

Laura didn’t know what to say. She hated the way she had to struggle to come up with words in Russian. She’d studied for years, since high school, and yet somehow in real conversations her mind kept going blank.

“Do you live around here?” she finally managed to ask.

“No. I live in Avtovo.” She had no idea where that was, and it must have showed on her face, because he added, “Second to last stop on the metro. Far away.”

“Oh.” She hadn’t been on the metro yet, but she’d looked at the map and knew that the city was huge, and that he must live on the outskirts. So what was he doing on Vasilievsky Island, walking around near the university?

“You are studying at the university?” he asked her.

“Yes. Until June.”

He nodded. They turned a corner and passed another long line, this one for vodka. A grizzled gray man with both front teeth missing grinned and pointed at her. She ignored him.

“Your Russian is pretty good.”

“Ha-ha. Thank you.”

“Of course you need a little practice. That’s normal.”

“I take five classes at the university,” Laura said. “Phonetics, Composition, Grammar, Translation, and —”

He cut her off. “Classes won’t help you. You need experience. In real life. To learn the real Russian.”

She nodded. It was hard to argue with that.

“And I would like to practice my English,” he added.

“Say something in English,” she said.

He gave a hesitant smile. “Eh … hello, Laura. Is nice day? I drive convertible car.”

She laughed. “That’s good.”

“You’re laughing at me.” He was speaking Russian again.

“No! It’s good! My Russian is no better.” Though she secretly suspected it was.

“Will you help me? We could practice together.” He stopped and rummaged through his duffel bag until he found a pencil and a scrap of paper. He wrote his name and a number on the paper and gave it to her. “This is my phone number. You can call me anytime.”

“Okay.” The numbers were neatly written, squared off like little designs.

“But listen.” They were a block away from the dorm. He didn’t seem to want to go farther. “Do not call me from the phone in your dorm.” He pointed to a red phone booth on the corner. “And not from this phone. Or from a phone booth anywhere near the university.”

“Then where should I call you from?”

He looked down the street, away from the dorm. “Walk five blocks that way — at least five blocks — and find a phone booth on the street. You can call me from there.”

“All right.” This was strange. Was he joking? They were no longer in a Tolstoy novel; now it was a spy story.

“Do you promise?”

“Yes. I promise. But why?”

He spoke in a low voice, almost a whisper. “Any phone booth near your dorm is sure to be bugged. They like to know what the foreign students are up to.”

“Oh.” They were in a spy novel. Or at least he thought they were. “Who are they?”

He flashed her a skeptical, pitying look, as if to say You really don’t know? And she did know what he meant, sort of. She’d heard stories of rooms that were bugged, American students sent home for fraternizing with the wrong people, Russian friends getting arrested for reasons that struck Americans as arbitrary and mysterious, impossible to understand. This was a totalitarian government, after all, and the sense that the government could do anything to anyone without explanation led to rampant paranoia.

“Do you promise to call me?” he asked.

She wasn’t sure, but she said, “I promise.”

“Good.” They stood awkwardly on the corner for a few seconds. A stocky, gray-haired woman bustled by with her string ba

g full of potatoes, giving Laura a good stare. “I would walk you to your dormitory, but I can’t.”

“I understand.”

“So you go, and I’ll go back over the bridge to the metro.”

“All right. Thank you for the pie. And for saving me on the bridge.”

“It’s nothing. You’ll call me?”

“I’ll call.”

She walked down the block to the dorm, pausing at the front door. She saw him in the distance, hiking over the bridge. He didn’t look back.

She looked at his phone number again, then put it in her coat pocket. For the first time since she’d arrived, she had someone to call, and the simple act of calling him was suffused with intrigue. Leningrad seemed to glimmer subtly in the growing dusk. The city was a new world. She felt herself being drawn in.

She’d call him. She knew she would.

Laura Reid could trace her interest in Russian to one particular day when she was ten.

Her fifth-grade teacher had read a book to the class called The Endless Steppe, by Esther Hautzig. Esther was a Jewish girl living in Poland during World War II whose family was arrested by the Soviets and exiled to Siberia. They starved, worked in the mines, and struggled to survive. It was the most terrible story Laura had ever heard, and she couldn’t stop thinking about it. The hardships of Siberia gripped her dreams at night as she snuggled in her warm, comfortable bed in her big, happy house in Baltimore.

She was taking French then, but her school offered Russian starting in the ninth grade. A senior came to Laura’s fifth-grade class to show a film on the history of the Russian czars: an endless parade of murder, insanity, terror, and betrayal set in wintry, golden palaces. The film included pivotal scenes acted out by “ghosts” — no actors were shown, but somehow invisible hands plunged knives into chests and hurled maces onto skulls. The scene that clinched it for Laura was the one where Ivan the Terrible — the name alone gave her a delicious shiver — killed his own son. The golden staff he used to murder his child crashed down onto an oriental carpet, which was quickly stained by a pool of blood. The camera closed in on a famous painting showing Ivan, his eyes bulging in horror, cradling his son’s bloody head, violins shrieking on the sound track.