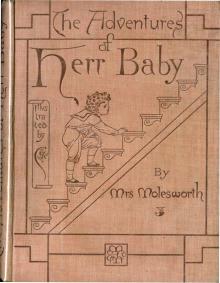

Adventures of Herr Baby

Mrs. Molesworth

THE ADVENTURES OF HERR BABY

by

MRS. MOLESWORTH

Author of 'Carrots,' 'Us,' Etc.

'I have a boy of five years old: His face is fair and fresh to see.' WORDSWORTH

Illustrated by Walter Crane

There was Baby, seated on the grass, one arm fondly clasping Minet's neck, while with the other he firmly held the famous money-box.--P. 138.]

LondonMacmillan and Co.and New York1895

First printed (4to) 1881Reprinted (Globe 8vo) 1886, 1887, 1890, 1892, 1895

CONTENTS

CHAPTER I.FOUR YEARS OLD 1

CHAPTER II.INSIDE A TRUNK 20

CHAPTER III.UP IN THE MORNING EARLY 41

CHAPTER IV.GOING AWAY 60

CHAPTER V.BY LAND AND SEA 81

CHAPTER VI.AN OLD SHOP AND AN OGRE 101

CHAPTER VII.BABY'S SECRET 125

CHAPTER VIII.FOUND 145

CHAPTER IX."EAST OR WEST, HAME IS BEST" 163

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

"OH LOOK, LOOK, BABY'S MADE PEEPY-SNOOZLE INTO'THE PARSON IN THE PULPIT THAT COULDN'T SAY HISPRAYERS,'" CRIED DENNY 6

HE SAT WITH ONE ARM PROPPED ON THE TABLE, AND HISROUND HEAD LEANING ON HIS HAND, WHILE THE OTHERHELD THE PIECE OF BREAD AND BUTTER--BUTTER DOWNWARDS,OF COURSE 16

THERE WAS ONE TRUNK WHICH TOOK MY FANCY MORETHAN ALL THE OTHERS 30

FOR A MINUTE OR TWO BABY COULD NOT MAKE OUT WHATHAD HAPPENED 50

"ZOU WILL P'OMISE, BETSY, P'OMISE CERTAIN SURE,NEBBER TO FORGET" 61

POOR LITTLE BOYS, FOR, AFTER ALL, FRITZ HIMSELFWASN'T VERY BIG! THEY STOOD TOGETHER HAND INHAND ON THE STATION PLATFORM, LOOKING, ANDFEELING, RATHER DESOLATE 84

"ARE THAT JOGRAPHY?" HE SAID 94

"OH AUNTIE," HE SAID, "P'EASE 'TOP ONE MINUTE.HIM SEES SHINY GLASS JUGS LIKE DEAR LITTLEMOTHER'S. OH, DO 'TOP" 106

BABY VENTURED TO PEEP ROUND. THE LITTLE BLACK-EYEDWHITE-CAPPED MAN CAME TOWARDS THEM SMILING 121

THERE WAS BABY, SEATED ON THE GRASS, ONE ARMFONDLY CLASPING MINET'S NECK, WHILE WITH THEOTHER HE FIRMLY HELD THE FAMOUS MONEY-BOX 138

AUNTIE STOOD STILL A MOMENT TO LISTEN 155

FORGETTING ALL ABOUT EVERYTHING, EXCEPT THAT HERBABY WAS FOUND, UP JUMPED MOTHER 170

THE ADVENTURES OF HERR BABY

CHAPTER I.

FOUR YEARS OLD

"I was four yesterday; when I'm quite old I'll have a cricket-ball made of pure gold; I'll never stand up to show that I'm grown; I'll go at liberty upstairs or down."

He trotted upstairs. Perhaps trotting is not quite the right word, but Ican't find a better. It wasn't at all like a horse or pony trotting, forhe went one foot at a time, right foot first, and when right foot wassafely landed on a step, up came left foot and the rest of Baby himselfafter right foot. It took a good while, but Baby didn't mind. He used tothink a good deal while he was going up and down stairs, and it was nothis way to be often in a hurry. There was one thing he could _not_ bear,and that was any one trying to carry him upstairs. Oh, that did vexhim! His face used to get quite red, right up to the roots of his curlyhair, and down to the edge of the big collar of his sailor suit, for hehad been put into sailor suits last Christmas, and, if the person whowas lifting him up didn't let go all at once, Baby would begin to wriggle.He was really clever at wriggling; even if you knew his way it was noteasy to hold him, and with any one that didn't know his way he could getoff in half a minute.

But this time there was no one about, and Baby stumped on--yes _that_ isa better word--Baby stumped on, or up, "wifout nobody teasing." His facewas grave, very grave, for inside the little house of which his two blueeyes were the windows, a great deal of work was going on. He was busywondering about, and trying to understand, some of the strange news hehad heard downstairs in the drawing-room.

"Over the sea," he said to himself. "Him would like to see the sea.Auntie said over the sea in a boat, a werry big boat. Him wonders howbig."

And his mind went back to the biggest boat he had ever seen, which wasin the toy-shop at Brookton, when he had gone with his mother to befitted for new boots. But even that wouldn't be big enough. Mother, andauntie, and grandfather, and Celia, and Fritz, and Denny, and cook, andLisa, and Thomas and Jones, and the other servants, and the horses,and--and---- Baby stopped to take breath inside, for though he had notbeen speaking aloud he felt quite choked with all the names coming sofast. "And pussy, and the calanies, and the Bully, and Fritz's dormice,oh no, them _couldn't_ all get in." Perhaps if Baby doubled up his legsunderneath he might squeeze himself in, but that would be no good, hecouldn't go sailing, sailing all over the sea by himself, like the oldwoman in "Harry's Nursery Songs," who went sailing, sailing, up in abasket, "seventy times as high as the moon." Oh no, even that boatwouldn't be big enough. They must have one as big as--and Baby stoppedto look round. But just then a shout from inside the nursery made himwake up, for he had got to the last little stair before the top landing,and again right foot and half Baby, followed by left foot and the otherhalf Baby, stumped on their way.

They pulled up--right foot and left foot, with Baby's solemn face top ofall--at the nursery door. It was shut. Now one of the things Baby likedto do for himself was to open doors, and now and then he could manage itvery well. But, alas, the nursery lock was too high up for him to get agood hold of it. He pulled, and pushed, and got quite red, all for nouse. Worse than that, the pushing and pulling were heard inside. Someone came forward and opened the door, nearly knocking poor Baby over.

"Ach, Herr Baby, mine child, why you not say when you come?" Lisa criedout. Lisa was Baby's nurse. Her face was rosy and round, and she lookedvery kind. She would have liked to pick him up to make sure he had gotno knocks, but she knew too well that would not do. So all she could dowas to say again--

"Mine child--ach, Herr Baby!"

Baby did not take any notice.

"Zeally," he said coolly, "ganfather must do somesing to zem locks. Zemis all most dedful 'tiff."

Lisa smiled to herself. She was used to Baby's ways.

"Herr Baby shall grow tall some day," she said. "Zen him can opendoors."

Lisa's talking was nearly as funny as Baby's, and, indeed, I ratherthink that hers had made his all the funnier. But, any way, theyunderstood each other. He was thinking over what she had said, when ascream from the nursery made them both turn round in a hurry.

"O Lisa, O Baby, come in quick, do. Peepy-Snoozle has got out of thecage, and he'll be out at the door in another moment. Quick, quick, comein and shut the door."

Lisa and Baby did not wait to be twice told. Inside the nursery therewas a great flurry. Celia, Fritz, and Denny were all there crawling overthe floor and screaming at each other.

"_I_ have him! there--oh, now that's too bad. Fritz, you frightened himaway again," called out Celia.

"_Me_ frighten him away! Why he knows me ever so much better than yougirls," said Fritz.

"He just doesn't then," said Denny with triumph, "for here he is safe inmy apron."

But she had hardly said the words when she gave a little scream. "He'soff again, oh quick, Baby, quick, catch him."

How Baby did it, I can't tell. His hands seemed too small to catchanything, even a dormouse. But catch the truant he did, and very proudBaby looked when he held up his t

wo little fists, which he had made intoa "mouse-trap" _really_, for the occasion, with Peepy-Snoozle's "coxy"little head and bright beady eyes poking out at the top.

"Oh look, look, Baby's made Peepy-Snoozle into 'the parson in the pulpitthat couldn't say his prayers,'" cried Denny, dancing about.

"All the same, he'd better go back into his cage," said Fritz, who had aright to be heard, as he was the master and owner of the dormice. "Comealong, Baby, poke him in."

Baby was busy kissing and petting Peepy-Snoozle by this time, for,though he did not approve of much of that sort of thing for himself, hewas very fond of petting little animals, who were not little boys. Andto tell the truth, it was not often he got a chance of petting his bigbrother's dormice. It was quite pretty to see the way he kissedPeepy-Snoozle's soft brown head, especially his nose, stroking it gentlyagainst his own smooth cheeks and chattering to the little creature.

"Dear little darling. Sweet little denkle darling," he said. "Him wouldlike to have a house all full of Peepy-'noozles, zem is so sweet andsoft."

"Wouldn't you like a coat made of their skins?" said Denny. "Think howsoft that would be."

"Oh look, look, Baby's made Peepy-Snoozle into 'the parson in the pulpit that couldn't say his prayers,'" cried Denny.--P. 6.]

"No, sairtin him wouldn't," said Baby. "Him wouldn't pull off all theirsweet little skins and hairs to make him a coat. Denny's a c'uel girl."

"There won't be much more skin or hairs left if you go on scrubbing himup and down with your sharp little nose like that," said Fritz.

Baby drew back his face in a fright.

"Put him in the cage then," he said, and with Fritz's help this wassafely done. Then Baby stood silent, slowly rubbing his own nose up anddown, and looking very grave.

"Him's nose _isn't_ sharp," he said at last, turning upon Denny. "Sharpmeans knifes and scidders."

All the children burst out laughing. Of course they understood thingsbetter than Baby, for even Denny, the youngest next to him, was nine,that is twice his age, which by the by was a puzzle to Denny herself,for Celia had teased her one day by saying that according to that whenBaby was eighty Denny would be a hundred and sixty, and nobody everlived to be so old, so how could it be.

But Denny, though she didn't _always_ understand everything herself, wasvery quick at taking up other people if they didn't.

"Oh, you stupid little goose," she said. "Of course, Fritz didn't meanas sharp as a knife. There's different kinds of sharps--there'sdifferent kinds of everything."

Baby looked at her gravely. He had his own way of defending himself.

"Werry well. If him's a goose him won't talk to you, and him won't tellyou somesing _werry_ funny and dedful bootiful that him heard in the'groind room."

All eyes were turned on Baby.

"Oh, do tell us, Baby darling, _do_ tell us," said Celia and Denny.

Fritz gave Baby a friendly pat on the back.

"You'll tell _me_, old fellow, won't you?" he said. Baby looked at him.

"Yes," he said at last; "him will tell you,'cos you let him havePeepy-'noozle, and 'cos you doesn't call him a goose--like _girls_ does.I'll whister in your ear, Fritz, if you'll bend down."

But Celia thought this was too bad.

"_I_ didn't call you a goose, Baby," she said. "I think you might tellme too."

"And I'll promise never to call you a goose again if you'll tell _me_,"said Denny.

Baby had a great soul. It was beneath him to take a mean revenge, hefelt, especially on a _girl_! So he shut his little mouth tightly, knithis little brows, and thought it over for a moment or two. Then hisface cleared.

"Him _will_ tell you all--all you children," he said at last, "but it'swerry long and dedful wonderful, and you mustn't inrumpt him. P'omise?"

"Promise," shouted the three.

"Well then, litsen. We's all goin' away--zeally away--over thesea--dedful far. As far as the sky, p'raps."

"In a balloon?" said Denny, whose tongue wouldn't keep still even thoughshe was very much interested in the news.

"No, in a boat," replied Baby, forgetting to notice that this was an"inrumption," "in a werry 'normous boat. All's going. Him was lookingfor 'tamps in mother's basket of teared letters under the little table,and mother and ganfather and auntie didn't know him were there, andganfather said to mother somesing him couldn't understand--somesingabout _thit_ house, and mother said, yes, 'twould be a werry good thingto go away 'fore the cold weather comed, and the children would bep'eased. And auntie said she would like to tell the children, but----"

Another "inrumption." This time from Fritz.

"Baby, stop a minute," he exclaimed. "Celia, Denny--Baby's too littleto understand, but," and here Fritz's round chubby face got very red,"don't you think we've no right to let him tell, if it's somethingmother means to tell us herself? She didn't know Baby was there--he saidso."

But before Celia or Denny could answer, Baby turned upon Fritz.

"Him _tolded_ you not to inrumpt," he said, with supreme contempt. "Ifyou would litsen you would see. Mother _did_ know him was there at theending, for auntie said she'd like to tell the children--that's you, andDenny and Celia--but him comed out from the little table and said _him_would like to tell the children hisself. And mother were dedfulsurprised, and so was ganfather and auntie. And then they all burstedout laughing and told him lots of things--about going in the railway,and in a 'normous boat to that other country, where there's cows to pullthe carts, and all the people talk lubbish-talk, like Lisa when she'scross. And zen, and zen, him comed upstairs to tell you."

Baby looked round triumphantly. Celia and Fritz and Denny looked firstat him and then at each other. This was wonderful news--almost toowonderful to be true.

"We must be going to Italy or somewhere like that," said Celia. "Howlovely! I wonder why they didn't tell us before?"

"Italy," repeated Denny, "that's the country like a boot, isn't it? I dohope there won't be any snakes. I'd rather far stay at home than gowhere there's snakes."

"_I_ wouldn't," said Fritz, grandly. "I'd like to go to India or Africa,or any of those places where there's lots of lions and tigers andsnakes, and anything you like. Give me a good revolver and _you'd_ see."

"Don't talk nonsense, Fritz," said Celia. "You're far too little a boyfor shooting and guns and all that. It's setting a bad example to Babyto talk that boasting way, and it's very silly too."

"Indeed, miss. Much obliged to you, miss," said Fritz. "I'd only justlike to know, miss, who it was came to my room the other night and wassure she heard robbers, and begged Fritz to peep behind the swing-doorin the long passage. And 'oh,' said this person, 'I do so wish you had agun that you could point at them to frighten them away.' Fritz wasn'tsuch a very little boy just then."

Celia's face got rather red, and she looked as if she was going to getangry, but at that moment, happily, Lisa appeared with the tray for thenursery tea. She had left the room when the dormouse was caught, so shehad not heard the wonderful news, and it had all to be told over again.She smiled and seemed pleased, but not as surprised as the childrenexpected.

"Why, aren't you surprised, Lisa?" said the children. "Did you knowbefore? Why didn't you tell us?"

Lisa shook her head and looked very wise.

"What country are we going to? Can you tell us that?" said Celia.

"Is it to your country? Is it to what you call Dutchland?" said Fritz."I think it's an awfully queer thing that countries can't be called bythe same names everywhere. It makes geography ever so much harder. We'vegot to call the people that live in Holland Dutch, and they callthemselves--oh, I don't know what they call themselves----"

"Hollanders," said Lisa.

"Hollanders!" repeated Fritz. "Well, that's a sensible sort of name forpeople that live in Holland. But _we've_ got to call them Dutch; andthen, to make it more muddled still, Lisa calls her country Dutchland,and the people Dutch, and _we_ call them German I think it's verystupid. If I was to make geography I woul

dn't do it that way."

"What's jography?" said Baby.

"Knowing all about all the countries and all the places in the world,"said Denny.

"Him wants to learn that," said Baby.

"Oh, you're _far_ too little!" said Denny. "_I_ only began it last year.Oh, you're ever so much too little!"

"Him's not too little to go in the 'normous boat to _see_ all zemcountlies," said Baby, valiantly. "Him _will_ learn jography."

"That's right, Baby," said Fritz. "Stick up for yourself. You'll be agreat deal bigger than Denny some day."

Denny was getting ready an answer when Lisa, who knew pretty well thesigns of war between Fritz and Denny, called to all the children to cometo tea; and as both Fritz and Denny were great hands at bread andbutter, they forgot to quarrel, and began pulling their chairs in to thetable, and in a few minutes all four were busy at work.

What a pretty sight, and what a pleasant thing a nursery tea is! whenthe children, that is to say, are sweet-faced and smiling, with cleanpinafores, and clean hands, and gentle voices; not leaning over thetable, knocking over cups, and snatching rudely at the "butteriest"pieces of bread and butter, and making digs at the sugar when nurse isnot looking. _That_ kind of nursery tea is not to my mind, and not atall the kind to which I am always delighted to receive an invitation,written in very round, very black letters, on very small sheets ofpaper. The nursery teas in Baby's nursery were not always _quite_ what Ilike to see them, for Celia, Fritz, and Denny, and Baby too, had theirtiresome days as well as their pleasant ones, and though they meant tobe good to each other, they did not _always_ do just what they meant, orreally wished, at the bottom of their hearts. But to-day all the littlestorms were forgotten in the great news, and all the faces looked brightand eager, though just at first not much was said, for when children arehungry of course they can't chatter quite so fast, and all the fourtongues were silent till at least one cup of tea, and perhaps three orfour slices of bread and butter each--just as a beginning, you know--haddisappeared.

Then said Celia,--

"Lisa, do tell us if you know what sort of a place we're going to."

"Cows pulls carts there," observed Baby; "and--and--what was the 'notherthing? We'll have frogses for dinner."

"Baby!" said the others, "_what nonsense_!"

"'Tisn't nonsense. Ganfather said Thomas and Dones wouldn't go 'cos theywas fightened of frogses for dinner. _Him_ doesn't care--frogses tasteswerry good."

"How do you know? You've never tasted them," said Fritz.

"Ganfather said zem was werry good."

"Grandfather was joking," said Celia. "I've often heard him laugh atpeople that way. It's just nonsense--Thomas and Jones don't know anybetter. Do they eat frogs in your country, Lisa?"

"In mine country, Fraeulein Celie?" said Lisa, looking rather vexed. "Noindeed. Man eats goot, most goot tings, in mine country. Say, HerrBaby--Herr Baby knows what goot tings Lisa would give him in hercountry."

"Yes," said Baby, "such good tings. Tocolate and cakes--lots--andbootiful soup, all sweet, not like salty soup. Him would like werry muchto go to Lisa's countly."

"Do cows pull carts in your country, Lisa?" asked Denny.

"Some parts. Not where mine family lives," said Lisa. "No, FraeuleinDenny, it's not to mine country we're going. Mine country is it colt, socolt; and your lady mamma and your lady auntie they want to go where itis warm, so warm, and sun all winter."

"_I_ should like that too," said Celia, "I hate winter."

"That's 'cos you're a girl," said Fritz; "you crumple yourself up by thefire and sit shivering--no wonder you're cold. You should come outskating like Denny, and then you'd get warm."

"Denny's a girl too. You said it was because I was a girl," said Celia.

"Well, she's not as silly as some girls, any way," said Fritz, rather"put down."

Baby was sitting silent. He had made an end of two cups of tea and fivepieces of bread and butter.

He was not, therefore, _quite_ so hungry as he had been at thebeginning, but still he was a long way off having made what was calledin the nursery a "good tea." Something was on his mind. He sat with onearm propped on the table, and his round head leaning on his hand, whilethe other held the piece of bread and butter--butter downwards, ofcourse--which had been on its way to his mouth when his brown study hadcome over him.

He sat with one arm propped on the table and his round head leaning on his hand, while the other held the piece of bread and butter--butter downwards, of course.--P. 16.]

"Herr Baby," said Lisa, "eat, mine child."

Baby took no notice.

"What has he then?" said Lisa, who was very easily frightened about herdear Herr Baby. "Can he be ill? He eats not."

"Ill," said Celia. "No fear, Lisa. He's had ever so much bread andbutter. Don't you want any more, Baby? What are you thinking about?We're going to have honey on our last pieces to-night, aren't we, Lisa?For a treat, you know, because of the news of going away."

Celia wanted the honey because she was very fond of it; but besidesthat, she thought it would wake Baby out of his brown study to hearabout it, for he was very fond of it too.

He did catch the word, for he turned his blue eyes gravely on Celia.

"Honey's werry good," he said, "but him's not at his last piece yet. Himdoesn't sink he'll _ever_ be at his last piece to-night; him's had tostop eating for he's so dedful busy in him's head."

"Poor little man, have you got a pain in your head?" said his sister,kindly. "Is that what you mean?"

"No, no," said Baby, softly shaking his head, "no pain. It's only busysinking."

"What about?" said all the children.

Baby sat straight up.

"Children," he said, "him zeally can't eat, sinking of what a dedfulpacking there'll be. All of everysing. Him zeally sinks it would be bestto begin to-night."

At this moment the door opened. It was mother. She often came up to thenursery at tea-time, and

"When the children had been good; That is, be it understood, Good at meal times, good at play,"

I need hardly say, they were very, very pleased to see her. Indeed therewere times even when they were glad to see her face at the door whenthey _hadn't_ been very good, for somehow she had a way of puttingthings right again, and making them feel both how wrong and how _silly_it is to be cross and quarrelsome, that nobody else had. And she wouldjust help the kind words out without seeming to do so, and take awaythat sore, horrid feeling that one _can't_ be good, even though one islonging so to be happy and friendly again.

But this evening there had been nothing worse than a little squabbling;the children all greeted mother merrily, only Baby still looked rathersolemn.