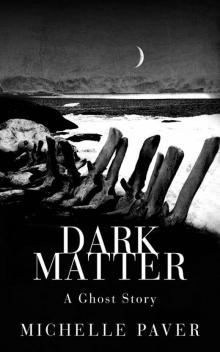

Dark Matter

Michelle Paver

Also by Michelle Paver

and published by Orion

Chronicles of Ancient Darkness

Wolf Brother

Spirit Walker

Soul Eater

Outcast

Oath Breaker

Ghost Hunter

Copyright

AN ORION EBOOK

First published in Great Britain in 2010 by Orion Books.

This eBook first published by Orion Books.

Copyright © Michelle Paver 2010

The rights of Michelle Paver to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All the characters and events in this book are fictitious, and any resemblance to real persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means without the prior permission in writing of the publisher, nor to be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published without a similar condition, including this condition, being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN: 978 1 4091 2380 4

This ebook produced by Jouve, France

Orion Books

The Orion Publishing Group Ltd

Orion House

5 Upper Saint Martin’s Lane

London, WC2H 9EA

An Hachette UK company

www.orionbooks.co.uk

Contents

Also by Michelle Paver and published by Orion

Copyright

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Author’s Note

Embleton Grange

Cumberland

24th November 1947

Dear Dr Murchison,

Forgive me for this rather belated reply to your letter.

You will I am sure understand why I found it hard to entertain your enquiry with any pleasure. To be blunt, you evoked painful memories which I have tried for ten years to forget. The expedition crippled a friend of mine and killed another. It is not something I care to revisit.

You mentioned that you are working on a monograph on ‘phobic disorders’, by which I take it you mean abnormal fears. I regret that I can tell you nothing which would be of assistance. Moreover, I fail to see how the ‘case’ (as you put it) of Jack Miller could provide appropriate material for such a work.

In your letter, you conceded that you know little of Spitsbergen, or indeed of anywhere else in what is often called the High Arctic. This is to be expected. Few people do. Forgive me, though, if I question how you would then propose to understand what it can do to a man to overwinter there. To battle the loneliness and desolation; yes, even with the many comforts that our modern age affords. Above all, to endure the endless dark. And as circumstances dictated, it was Jack’s misfortune to be there alone.

I don’t think we will ever learn the truth of what happened at Gruhuken. However I know enough to be convinced that something terrible took place. And whatever it was, Dr Murchison, it was real. It was not the result of some phobic disorder. And in this respect I would add that before entering politics I undertook some years of study in the sciences, and thus feel myself entitled on two counts to be considered a reasonable judge of evidence. Moreover, no one has ever doubted my sanity, or proposed to include my ‘case’ in a monograph.

I don’t know how you came by the knowledge that Jack Miller kept a journal on the expedition, but you are right, he did. I saw him writing in it many times. We used to rag him about it, and he took this in good part, although he never showed us its contents. No doubt the journal would, as you suggest, explain much of what happened; but it has not survived, and I cannot ask Jack himself.

Thus I fear that I am unable to help you. I wish you well with your work. However I must ask you not to apply to me again.

Yours sincerely,

Algernon Carlisle

1

Jack Miller’s journal

7th January 1937

It’s all over, I’m not going.

I can’t spend a year in the Arctic with that lot.They arrange to ‘meet for a drink’,then give me a grilling,and make it pretty clear what they think of a grammar-school boy with a London degree.Tomorrow I’ll write and tell them where to put their sodding expedition.

The way they watched me when I entered that pub.

It was off the Strand,so not my usual haunt, and full of well-to-do professional types.A smell of whisky and a fug of expensive cigar smoke.Even the barmaid was a cut above.

The four of them sat at a corner table, watching me shoulder my way through. They wore Oxford bags and tweed jackets with that elegantly worn look which you only acquire at country house weekends. Me in my scuffed shoes and my six-guinea Burton’s suit. Then I saw the drinks on the table and thought, Christ, I’ll have to buy a round, and I’ve only got a florin and a threepenny bit.

We said our hellos, and they relaxed a bit when they heard that I don’t actually drop my aitches, but I was so busy wondering if I could afford the drinks that it took me a while to work out who was who.

Algie Carlisle is fat and freckled, with pale eyelashes and sandy-red hair; he’s a follower rather than a leader, who relies on his pals to tell him what to think. Hugo Charteris-Black is thin and dark, with the face of an Inquisitor looking forward to putting a match to another heretic. Teddy Wintringham has bulging eyes that I think he thinks are penetrating. And Gus Balfour is a handsome blond hero straight out of The Boy’s Own Paper. All in their mid-twenties, but keen to appear older: Carlisle and Charteris-Black with moustaches, Balfour and Wintringham with pipes clamped between their teeth.

I knew I hadn’t a chance, so I thought to hell with it, give it to them straight: offer yourself like a lamb to the slaughter (if lambs can snarl). So I did. Bexhill Grammar, Open Scholarship to UCL. The slump putting paid to my dreams of being a physicist, followed by seven years as an export clerk at Marshall Gifford.

They took it in silence, but I could see them thinking, Bexhill, how frightfully middle class; all those ghastly mock-Tudor dwellings by the sea. And University College . . . not exactly Oxbridge, is it?

Gus Balfour asked about Marshall Gifford, and I said, ‘They make high-quality stationery, they export all over the world.’ I felt myself reddening. God Almighty, Jack, you sound like Mr Pooter.

Then Algie Carlisle, the plump one, asked if I shoot.

‘Yes,’ I said crisply. (Well, I can shoot, thanks to old Mr Carwardine, DO, retired, of the Malaya Protectorate, who used to take me on to the Downs after rabbits; but that’s not the kind of shooting this lot are used to.)

No doubt Carlisle was thinking the same thing, because he asked rather doubtfully if I’d got my own gun.

‘Service pattern rifle,’ I said. ‘Nothing special, but it does OK.’

That elicited a collective wince, as if they’d never heard slang before.

Teddy Wintringham mentioned wirelessing and asked if I knew my stuff. I said I should think so, after six years of night technical school, both the General and Advanced courses; I wanted something practical that would keep me in touch with physics. (More Mr Poot

er. Stop wittering.)

Wintringham smiled thinly at my discomfort. ‘No idea what any of that means, old chap. But I’m told that we rather need someone like you.’

I gave him a cheery smile and pictured blasting a hole in his chest with said rifle.

It can’t have been that cheery, though, because Gus Balfour – the Honourable Augustus Balfour – sensed that things were veering off track, and started telling me about the expedition.

‘There are two aims,’ he began, looking very earnest and more like a schoolboy hero than ever. ‘One, to study High Arctic biology, geology and ice dynamics. To that end we’ll be establishing a base camp on the coast, and another on the icecap itself – which is why we’ll be needing a team of dogs. Secondly, and more importantly, a meteorological survey, transmitting observations three times a day for a year, to the Government forecasting system. That’s why we’re getting help from the Admiralty and the War Office. They seem to think our data will be of use if – well, if there’s another war.’

There was an uneasy pause, and I could see them hoping we wouldn’t get side-tracked into discussing the situation in Spain and the neutrality of the Low Countries.

Turning my back on world politics, I said, ‘And you’re planning to achieve all that with only five men?’

This drew sharp glances from the others, but Gus Balfour took it in good part. ‘I know it’s a tall order. But you see, we have thought about this. The plan is, Algie will be chief huntsman, dog-driver and geologist. Teddy’s the photographer and medico. Hugo’s the glaciologist for the icecap side of things. We’ll all lend a hand with the meteorology. I’ll be the biologist and, um, Expedition Leader. And you’ll be—’ He broke off with a rueful laugh. ‘Sorry, we hope you’ll be our communications man.’

He seemed genuinely keen to win me over, and I couldn’t help feeling flattered. Then Hugo Charteris-Black, the Inquisitor, spoiled it by demanding to know why I wanted to come, and was I quite sure I understood what I’d be letting myself in for?

‘You do realise what the winter will be like?’ he said, fixing me with his coal-black stare. ‘Four months of darkness. Think you can take it?’

I gritted my teeth and told him that was why I wanted to go: for the challenge.

Oh, they liked that. I expect it’s the sort of thing you’re taught at public school. I was glad I hadn’t told them the real reason. They’d have been mortified if I’d said I was desperate.

I couldn’t put off buying my round any longer. Pints for Algie Carlisle, Teddy Wintringham and Hugo Charteris-Black (at sevenpence a go), a half for me (that’s another threepence halfpenny). I was thinking I wasn’t going to manage it when Gus Balfour said, ‘Nothing for me.’ He made quite a convincing job of it, but I could tell that he was trying to help me out. It made me feel ashamed.

After that, things went OK for a while. We worked our way through our drinks, and then Gus Balfour glanced at the others and nodded, and said to me, ‘Well, now, Miller. Would you care to join our expedition?’

I’m afraid I got a bit choked. ‘Um, yes,’ I said. ‘Yes, I should think I would.’

The others looked merely relieved, but Gus Balfour seemed genuinely delighted. He kept clapping me on the back and saying, ‘Good show, good show!’ I don’t think he was putting it on.

After that we fixed our next meeting, and then I said my goodbyes and headed for the door. But at the last moment, I glanced over my shoulder – and caught Teddy Wintringham’s grimace and Algie Carlisle’s fatalistic shrug. Not exactly a sahib, but I suppose he’ll have to do.

Stupid to be so angry. I wanted to march back and smash their smug faces into their overpriced drinks. Do you know what it’s like to be poor? Hiding your cuffs, inking the holes in your socks? Knowing that you smell because you can’t afford more than one bath a week? Do you think I like it?

I knew then it was hopeless. I couldn’t be part of their expedition. If I can’t put up with them for a couple of hours, how could I stand a whole year? I’d end up killing someone.

Later

Jack, what the hell are you doing? What the hell are you doing?

As I headed home, the fog on the Embankment was terrible. Buses and taxicabs creeping past, muffled cries of paper boys. Street lamps just murky yellow pools, illuminating nothing. God, I hate fog. The stink, the streaming eyes. The taste of it in your throat, like bile.

There was a crowd on the pavement, so I stopped. They were watching a body being pulled from the river. Someone said it must be another poor devil who couldn’t find work.

Leaning over the parapet, I saw three men on a barge hauling a bundle of sodden clothes on to the deck. I made out a wet round head, and a forearm which one of the gaffs had ripped open. The flesh was ragged and grey, like torn rubber.

I wasn’t horrified, I’ve seen a dead body before. I was curious. And as I stared at the black water I wondered how many others had died in it, and why doesn’t it have more ghosts?

You’d have thought that brush with mortality would have put things in perspective, but it didn’t. I was still seething when I reached the tube station. In fact I was so angry that I overshot my stop and had to get out at Morden and backtrack to Tooting.

The fog was thicker in Tooting. It always is. As I groped my way up my road, I felt like the last one left alive.

The stairs to the third floor smelt of boiled cabbage and Jeyes’ Fluid. It was so cold I could see my breath.

My room wasn’t any better, but I had my anger to keep me warm. I grabbed my journal and spewed it all out. To hell with them, I’m not going.

That was a while ago.

My room is freezing. The gas jet casts a watery glimmer that shudders whenever a tram thunders past. I’ve got no coal, two cigarettes, and twopence half-penny to last till payday. I’m so hungry my stomach’s given up rumbling because it knows there isn’t any point.

I’m sitting on my bed with my overcoat on. It smells of fog. And of the journey I’ve taken twice a day, six days a week, for seven years with all the other grey people. And of Marshall Gifford, where they call me ‘College’ because I’ve got a degree, and where for three pounds a week I track shipments of paper to places I’ll never see.

I’m twenty-eight years old and I hate my life. I never have the time or the energy to work out how to change it. On Sundays I trail round a museum to keep warm, or lose myself in a library book, or fiddle with the wireless. But Monday’s already looming. And always I’ve got this panicky feeling inside, because I know I’m getting nowhere, just keeping myself alive.

Tacked above the mantelpiece is a picture called ‘A Polar Scene’ that I cut out from the Illustrated London News. A vast, snowy land and a black sea dotted with icebergs. A tent, a sledge and some husky dogs. Two men in Shackleton gear standing over the carcass of a polar bear.

That picture is nine years old. Nine years ago I cut it out and tacked it above the mantelpiece. I was in my second year at UCL, and I still had dreams. I was going to be a scientist, and go on expeditions, and discover the origins of the universe. Or the secrets of the atom. I wasn’t quite sure which.

That’s when it hit me: just now, staring at ‘A Polar Scene’. I thought of the body in the river and I said to myself, Jack, you idiot. This is the only chance you’ll ever get. If you turn it down, what’s the point of going on? Another year at Marshall Gifford and they’ll be fishing you out of the Thames.

It’s five in the morning and the milk floats are rattling past under my window. I’ve been up all night and I feel amazing. Cold, hungry, light-headed. But amazing.

I keep seeing old man Gifford’s face. ‘But Miller, this is madness! In a few years you could be Export Supervisor!’

He’s right, it is mad. Chuck in a secure job at a time like this? A safe job, too. If there is another war, I’d be excused combat.

But I can’t think about that now. By the time I get back, there probably will be another war, so I can go off and fight. Or if there isn’t

, I’ll go to Spain and fight.

It’s odd. I think war is coming, but I can’t feel much about it. All I feel is relief that Father isn’t alive to see it. He’ll never know that he fought the War to End All Wars for nothing.

And as I said, it doesn’t seem real. For this one year, I’m going to get away from my life. I’m going to see the midnight sun, and polar bears, and seals sliding off icebergs into green water. I’m going to the Arctic.

It’s six months till we sail for Norway. I’ve spent the whole night planning. Working out how soon I can hand in my notice and still survive till July. Going through the Army & Navy Price List, marking up kit. I’ve drafted a fitness plan and a reading list, because it occurs to me that I don’t actually know very much about Spitsbergen. Only that it’s a clutch of islands halfway between Norway and the Pole, a bit bigger than Ireland, and mostly covered in ice.

When I started this journal, I was convinced I wouldn’t be going on the expedition. Now I’m writing because I need to record the exact moment when I decided to do this. The body in the river. If it hadn’t been for that poor bastard, I wouldn’t be going.

So thank you, nameless corpse, and I hope you’re at peace now, wherever you are.

I am going to the Arctic.

That picture above the mantelpiece, I’ve just noticed. There’s a seal in the foreground. All these years and I thought it was a wave, but actually it’s a seal. I can make out its round, wet head emerging from the water. Looking at me.

I think I’ll take that as a good omen.

2

24th July, The Grand Hotel, Tromsø, north Norway

I didn’t want to write anything more until we reached Norway, for fear of tempting fate. I was convinced that something would happen to scupper the expedition. It nearly did.

Two days before we were due to set off, Teddy Wintringham’s father died. He left a manor in Sussex, ‘some village property’, a tangle of trusts and a clutch of dependants. The heir was ‘most frightfully cut up’ (about the expedition, not his father), but although he felt ‘absolutely ghastly’ about it, it simply wouldn’t do for him to be gone a year, so he had to scratch.