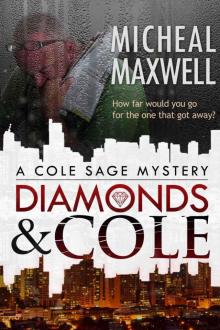

Diamonds and Cole: A Cole Sage Mystery

Micheal Maxwell

Three Nails is a tale of tragedy, redemption, and hope from the author of the bestselling Cole Sage series. To receive a free ebook copy straight to your inbox, click here.

DIAMONDS AND COLE

__________________________

A Cole Sage Mystery

MICHEAL MAXWELL

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Diamonds and Cole

About the Author

Excerpt from Cellar Full of Cole

Also by Micheal Maxwell

Copyright

DIAMONDS AND COLE

ONE

Cole flicked a pickle onto the grass just across the sidewalk. He slapped the bun in his hands back together and took a bite. Just not the same as they used to be, he thought. Hamburgers had been his favorite food as a child, now he rarely ate them. Sometimes he wondered, What is the use? He bought the burger only because he needed comfort food. He really wanted mashed potatoes and gravy-dark, thick, heavily peppered gravy. He had no idea where to get gravy like he wanted anymore, so he settled for the burger. On the way to the park, it seemed like just the thing. It wasn’t. Now he just felt like giving up.

She liked pickles. All these years later, he still remembered that. Frowning deeply, he gazed down at the sidewalk. She hated olives, though. They used to order pizza, a large combo, and she would pick off all the olives. He asked her once, why don’t we just order it without the olives? She said she didn’t want to be any bother. A faint smile crossed his lips. He dropped the unfinished burger into the bag. As he crossed the park, he dropped the bag into a rusted out garbage can and gave a half-hearted grin.

What do you suppose she’s doing today? Cole wondered. He drifted toward the edge of the park and slid deeper into memory. Who is that singer she liked? Kenny somebody. It’d been longer than he thought. A tall, thin, gay couple, skated past him hand-in-hand. Rankin, Kenny Rankin, that’s his name. Kind of jazzy style, really messed up the Beatle songs, especially Blackbird. He remembered how he borrowed a Rankin album, on her insistence, and how it warped in the trunk of the car. He knew he wouldn’t like it; in fact, it never even made it into the house. His stomach tightened with the guilt of never replacing it. Oh, how he longed to hear Kenny Rankin sing Blackbird.

He reached in his pocket for his car keys.

“Wash your windows?”

“No thanks,” Cole said without looking up.

Turning at the sound of guttural muttering, Cole was inches from one of the myriad of homeless people that had invaded the park in the last year. The dirty figure sneered and seemed to grow taller and more erect from the refusal. The thin frame, shoulders pulled back, and chest thrown out, suddenly became the taller of the two men now facing each other on the sidewalk. His pants were held up by a thick piece of rope knotted twice in the front. The extra rope was tucked into his front pockets. A set of ribs showed from under the green army blanket slung over his right shoulder and tied chest-high with a second piece of rope.

“Wash your windows!” The request had become a demand.

“No. I don’t want my windows washed.”

“What? You think you’re better than me? I got rights.”

“Rights?”

“I can earn a living same as you. Suits don’t rule everything. I got rights.”

“Me too. Get out of my way. I said I don’t want my window washed.”

“There is gonna be a revolution, and you’re gonna die!”

“That’s it! Get the hell out of my way.” Cole said, getting into his car.

“Rise up! Rise up!” the window washer screamed. “The revolution starts here. The revolution starts now!” His screams seemed to ricochet off the buildings. Suddenly, there was a small crowd of people watching. The army blanket now waved over the window washer’s head, like a battle flag, rallying an army of revolutionaries, who had yet to show up.

The skeletal form of the window washer in the rear view mirror seemed a pale translucent blue in the crisp April air. As the engine turned over, a half-empty, plastic spray bottle, bounced off the back window.

“I don’t need this,” Cole muttered, putting the car in reverse.

The window washer began pounding on the roof above the passenger-side window. “You can run, but you can’t hide!” he screamed.

“Oh, please,” Cole groaned as the car inched back. The pounding on the roof of the car sounded like a huge kettledrum. Turning, he saw the emaciated derelict at his window, fumbling with the rope that held up his ragged Ben Davis khakis. The oversized trousers dropped to the ground, and the window washer grabbed his penis and shook it towards the window.

“We know who you are! We will hunt you down! You will pay!” The window was suddenly awash in yellow-brown fluid.

“I don’t need this. Not today.” Cole dropped the car into drive and accelerated away from the curb.

In the rearview mirror, the thin bluish figure stood in the middle of the street, khakis around his ankles and fists raised in the air screaming, “Rise up! Rise up! Up, up, up, up!”

Merging into the after-lunch traffic, Cole shifted his weight, settled into the well-worn seat, and laughed. The laugh wasn’t because he was amused. It was the only thing he could do. To his amazement, he started to cry. Real tears ran down his cheeks, and blurred his vision; real tears mixed with the sound of sobbing laughter.

He tossed his sunglasses onto the stack of newspapers on the seat next to him, and wiped his eyes with the back of his hand. He never felt so lonely, and he was used to being alone. This was different, though; it was a deep aching sort of my-mother-just-died-and-nobody-knows-my-name freefall into alone.

A doctor would probably diagnose depression, and give him some happy pills. It was depression all right, but not the kind the doctor would see. Cole knew the cause, he knew the cure, but it was about twenty years too late for that. Lately, he had just been down. Maybe it was the onslaught of middle age; maybe it was not having someone or something he felt he belonged to. He used to love his job. Now, it was a job. The fire was gone, the focus, the purpose, or whatever you wanted to call it.

Cole had too many memories. Places he had been, people he’d known, things he’d seen. But they all came back around to her. She was the greatest thing in his life, and the worst. He lost her. Why she started haunting his thoughts was a mystery.

For the last two years, she’d been on his mind. He told himself he should find her, talk to her. He knew it wouldn’t do any good. It had been over twenty years since he had seen her.

In the years since they parted, he had done all the things in life he set out to do except marry her. All the awards, all the acclaim, seemed so important at the time. He kept a feverish pace for years. It had been a time of turmoil and change in the world, and he’d been there. Politics, war, and scandal; he’d written about it all. Racism, hunger, ethnic cleansing; he’d stared it in the face. Pol Pot, Muammar al-Gaddafi, Slobodan Milosevic, Bill Clinton, and both George Bushes had looked him in the eye and told their version of the truth. His name was well known, and in most cases respected, or had been.

Then it all began to fall apart, or he did. He didn’t have the usual excuses. It wasn’t liquor or drugs, it wasn’t women: It was woman. The one that got away. Maybe she was just an excuse. He slowed down, got tired, gave up. Whatever you wanted to call it, nothing had much meaning anymore. All is vanity, he’d thought time and again. All the words he’d written, all the miles he’d flown didn’t lay a foundation for what was to come: a life without her.

Now, after a career spent at The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, and Time Magazine he was back where he started: The Chicago Sentinel. Not as an editor, like one would

expect, as a reward for such a distinguished career, but as a staff writer. No longer finding the news, or digging for the truth behind the headlines, now he was assigned a story. Every Friday he collected a check for writing the kind of shallow drivel any first-year rookie could probably improve upon.

Two nights ago, Cole had cried watching old footage of Richard Nixon’s resignation speech on TV. He cried like Old Yeller just died, didn’t stop for nearly an hour. Nixon knew how he felt. Nixon had been alone. He never liked Nixon, but he knew what he was feeling, and when Nixon’s voice cracked, so had Cole Sage.

TWO

Opening the front door of The Sentinel building felt to Cole like he was pushing it through sand. He really didn’t want to go in. He could think of a thousand reasons to go in. ‘Have to’ reasons but no ‘want to’ reasons. He used to fly through the doors on the run, heart pounding, adrenaline pumping. He used to be the hot-shit reporter with the scoop of the day. Now, he was doing well if he met the deadline for the stories the night editor assigned him.

Mick Brennan tried to throw Cole a bone now and again, but Brennan was tired and burned out. When Cole first came to the paper, Brennan became his mentor. “Got a ways to go, kid,” he used to say. Brennan showed Cole that he hadn’t really learned anything in college, and un-taught him the bad habits he picked up there. Write, write, and rewrite. Brennan used up boxes of red copy proof pencils, and turned Cole into a first-class newspaperman. Cole would have done anything to show Mick he could do it his way: the best way. But he never got it quite good enough. Never a compliment, always a kick in the teeth. That was Brennan’s style.

Cole had introduced her to Mick Brennan after spinning tales of the great newspaperman, and how much he meant to him.

“Too good for you, Cole,” was all Brennan said as he walked away.

Cole could still see the hurt in her eyes as they walked back to the elevator. Something broke that day. A bond, an unspoken, gentleman’s understanding, between the new kid and the old lion, the hero and the eager-to-please sidekick. It was gone. Not long after that, Cole was gone too. That was the first time he quit The Sentinel.

Cole had been 22 and Mick 42. Somehow, it was now twenty-odd-years later.

“What’s the problem? You wanna move it?” a harsh voice jabbed from behind.

A brown shirt delivery man, heavy boxes to his chin, stood glaring at Cole. Attitudes seemed to be growing out of the sidewalk. When did service providers become the aggressors in the war on civility? It would have been easy to have shot back a smart rebuke to his societal underling, but why bother? The world Cole now lived in was beyond dueling with taunt-calved, community college dropouts, in tight brown shorts. He pushed the door open, then let it swing back to hit the boxes. As the slurs and curses flew at his back, Cole went through the door marked ID Badges Required beyond This Point.

“Afternoon, Cole.”

“Greetings, Queen Jean.”

Cole barely glanced at the black woman behind the front desk. How life changes things. Years before, as a new staff reporter, he had bribed a kid guarding the front door of a burned-out apartment building $20 to get as far as the third floor, in hopes of getting an interview with Tashira, the firebrand orator of the Black Women’s Urban Army. The Army hated men, hated whites, and really hated white men, but up he went, and banged on the door like the landlord after late rent. An hour later, he left with a notepad full of quotes, and a recipe for sweet potato pie. That was a different world. Ideals, high hopes, and a heartfelt belief in something, that drove people to actually try to change the world. After five kids, 50 added pounds, and three men who took what they wanted and left with the first bump in the road, Tashira once again become Olajean Baker. The radical daughter of the single hotel maid mother, who raised her to fight back, just celebrated her 10th year of sobriety, and being the front desk receptionist at The Sentinel. A job she had thanks to Cole Sage. When the revolutionary fire had gone out in her, Cole still remembered the heart that burned white-hot for what should have been.

“Brennan’s been asking for you. Something about a dead kid or somethin’. I really didn’t get much out of it.”

Cole gave her that silent smile that was now all-too-familiar, and slipped through the swinging door at the counter.

Olajean seemed content. Why am I so miserable? Cole thought. Maybe it was turning 45. He always believed he would die in some adventurous blaze of glory. He got shot at in the Philippines, saw a car bomb go off in front of his hotel in Tel Aviv, and received enough death threats to wallpaper The Sentinel building. But here he was. When had he given up? Twenty-five years in the news business and he was at the bottom. No, lower than the bottom. He started at the bottom, and he was even lower now.

No one looked up as he made his way through the maze of cubicles. Mini flowerpots, kitty posters, and pictures of little leaguers, soccer stars, Brad Pitt, and big-eyed cartoon children blurred past him as he made his way to his corner of the world. Coffee cups, stacks of paper, and an old “Coming Soon to the Bijou” flyer decorated his carpeted “office.”

Cole made a half-hearted attempt at straightening his tie. He exhaled deeply as he stared at the numbers on the phone. Punching in 784, he waited.

“Brennan.”

“What’s up?”

“What, I don’t warrant an in-person audience?”

“Thought it...” Cole paused, not having an answer. “I thought I’d save time. Something about a dead kid?”

“Dead kitten. Seems a dozen people tried to get this cat out of a tree until some guy used a swimming pool net on a long aluminum pole. Looks like it touched a power line about the time it snagged the cat. Fried the kitty and shocked the shit out of the guy holding the pole. Anyway, follow it up, would ya? Natoma and 125th.”

“That’s it?”

“Yep, need filler. Nothing really happening today.” Brennan hung up.

A dead cat. Cole just stared, phone to his ear, dial tone humming. The movement of a copy clerk caught his eye. He knew he had to cover the story. That was the ache. Why didn’t he quit? The resounding echo was always, To do what?

Cole left his coat draped on the back of his swivel chair, and stood looking over the tops of the cubical walls; a sea of gray carpeted boxes, filled with people doing God-knows-what. At the far-end of the room stood three people deep in conversation. Next to them was the water cooler. Cole was not below eavesdropping. He made his way back to the trio.

“It’s stealing from the city plain and simple,” groaned an Asian man in a Georgetown sweatshirt.

“Prove it, Lionel. How are you going to prove it? Facts, remember?” challenged a tall acne-scarred man Cole knew as Katz. Cole didn’t like him. Katz always sounded like he read too many Superman comics, and never realized that Jimmy Olson wasn’t the hero.

Erica Sloan, whose bad haircut and wardrobe matched her writing style, chimed in. “Contractors can apply for low-cost city loans as long as they are either renovating existing buildings in low-income areas or building new low-income housing. It has been this way for years. What’s the big deal?” Cole helped train her when she first came on the paper. She was smart and knew it, still finding news, just like he taught her.

Cole filled a cup with cold filtered water. No news here, he thought as he turned to go back to his desk.

“Hi Mr. Sage, workin’ on anything big?” Katz beamed when he caught sight of Cole.

“He really is Jimmy Olson,” Cole muttered.

“Carl.”

“What?”

“My name is Carl, not Jimmy.”

“Of course it is, sorry,” returned Cole.

Carl Katz, now why isn’t he working on this story? Just think of the headline possibilities combined with his byline. Cole actually chuckled to himself.

Clouds rolled in from the east. No chance of rain, but enough to cast a gray shadow on the day. Cole enjoyed the cool breeze on his face. His tie flapped in the wind as he walked to the car. Long ago he gave up t

ightening his ties. His uniform was pretty much the same year after year: Levis, an oxford cloth, button-down collar shirt, and a Harris Tweed sports coat, with oval leather patches on the elbows. He owned three tweed sports coats. Gray for important meetings, interviews, or the rare occasion he was trying to impress someone. Dark brown for those, more and more frequent, dark days, when he didn’t feel like leaving his apartment. And camel-colored, his personal favorite, for the times he really needed to feel like his old self. Today he wore the dark brown.

* * *

Natoma Street was in the old part of the city, canopied with handsome old trees that lined streets, always keeping it cool and shady in summer. Cole always loved how the huge, old, ash trees loomed over the street, growing together and forming a massive green arch. Small houses set deep on the lots looked like little gingerbread houses. Ivy climbed and covered the chimneys. The lawns were all edged and mowed. Cole always wished he could have lived in a neighborhood just like the Montclare District.

As he turned up Natoma, a Community Service Officer flagged him down. “Sorry, sir, road’s closed.”

Cole showed the officer his press credentials and asked, “All this for a dead cat?”

“A bit more serious than that. Seems the old lady who owned the cat has taken the guy who killed it hostage. Says she’s got a shotgun. Nobody can get to her.”

“Where can I park?”

The officer pointed to the left side of the street behind an ambulance. “I guess that would be okay.”

“Hey, who’s in charge?” Cole yelled as he pulled away.

“Harris. Lieutenant Harris.”

The small street was crammed with fire engines, ambulances, six police cruisers, and three or four navy blue, unmarked, Crown Victorias doing their best to look inconspicuous. The picture-perfect landscapes were strung with yellow police tape and patrolmen. Neighbors from all over the district were pressing against the barricades, and chatting about how nothing like this ever happened here before. Cole approached a bored-looking patrolman who was leaning against the back of a black-and-white, smoking.