The Laughter of Carthage: The Second Volume of the Colonel Pyat Quartet (Colonel Pyat Quartet Series Book 2)

Michael Moorcock

MICHAEL MOORCOCK

Winner of the Nebula and World Fantasy awards

August Derleth Fantasy Award

British Fantasy Award

Guardian Fiction Award

Prix Utopiales

Bram Stoker Award

John W. Campbell Award

SFWA Grand Master

Member, Science Fiction and Fantasy Hall of Fame

Praise for Michael Moorcock and The Laughter of Carthage

‘Michael Moorcock is an absolute wizard of a storyteller. I can think of no writer like him, not here, not America. He is a wonder…. It is marvelous to meet a novelist who has the energy for the epic. It is not simply a case of energy, Mr Moorcock is also a storyteller, an old-fashioned buttonholing, nineteenth-century storyteller.’

—Stanley Reynolds, Punch

‘He is an ingenious and energetic experimenter, restlessly brimming over with clever ideas.’

—Robert Nye, The Guardian

‘This is epic writing …’

—Valentine Cunningham, Times Literary Supplement

‘If you are at all interested in fantastic fiction, you must read Michael Moorcock. He changed the field singlehandedly: he is a giant. He has kept me entertained, shocked and fascinated for as long as I have been reading.’

—Tad Williams

‘The greatest writer of post-Tolkien British fantasy.’

—Michael Chabon

’The Laughter of Carthage is a formidable … work in which science and technology are subordinated to narrative techniques not usually found in popular fiction … a work of grand design … cast as Pyatnitski’s memoirs of a life uprooted by the Russian Revolution. He brags of his exploits as a Don Cossack; he claims pure Russian blood and a batch of patents for airplanes and automobiles. But one can never be sure that anything Pyatnitski says is true. He is certainly an egomaniac and very likely mad; he is also a reactionary Tom Swift, an anti-Semite, a sybarite and a paranoiac with a gargantuan appetite for cocaine. Rabid anti-Semitism is his way of denying the past and advancing his career as scientist and gentleman. There is also ample indication of a thin line between deceit and self-delusion. Pyat’s first stop on his flight from Bolshevism is Istanbul, a teeming cosmopolis of thieves and whores but also a site idealized as the bastion of a once glorious Christendom. From there, the grotesque innocent moves west through Rome, Paris, New York City and Hollywood. Moorcock takes large risks … there are rewarding detours: lush descriptions of landscapes and the world’s great cities, and a parade of characters that would feel at home in the novels of Dickens, Nabokov and Henry Miller.’

—Time magazine

‘No one at the moment in England is doing more to break down the artificial divisions that have grown up in novel writing—realism, surrealism, science fiction, historical fiction, social satire, the poetic novel—than Michael Moorcock.’

—Angus Wilson

‘There is a feast in store for those who have never been dazzled and disturbed by Michael Moorcock’s eye for the absurd and gift for fantasy, and confirmation for those familiar with his work, that he is one of the most original authors of our time.’

—Sunday Telegraph

The Laughter of Carthage: The Second Volume of the Colonel Pyat Quartet

Michael Moorcock

© 2012 by Michael Moorcock

This edition © 2012 PM Press

Introduction © 2012 by Alan Wall

ISBN: 978-1-60486-492-2

Library of Congress Control Number: 2011939673

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be transmitted by any means without permission in writing from the publisher.

Bibliography reprinted with the kind permission of Moorcock’s Miscellany (www.multiverse.org)

Project editor: Allan Kausch

Copy editor: Gregory Nipper

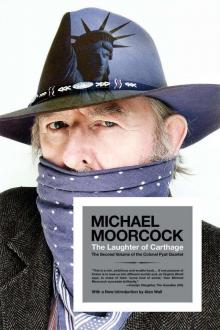

Cover by John Yates/www.stealworks.com

Interior design by briandesign

Copyright © Michael Moorcock 1984

Cover photo by Linda Steele

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

PM Press P.O.

Box 23912

Oakland, CA 94623

PMPress.org

Printed in the USA on recycled paper, by the Employee Owners of Thomson-Shore in Dexter, Michigan.

www.thomsonshore.com

To the memory of Stokely Carmichael and a time when we seemed to be doing our best a little better than we’re doing it now.

For Michael Dempsey, Alexis Korner, Mongasi Feza

Contents

INTRODUCTION BY ALAN WALL

INTRODUCTION BY MICHAEL MOORCOCK

The Laughter of Carthage

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Introduction to

The Laughter of Carthage

We are addicted to narrative. Perhaps it is entailed in our status as the only fully linguistic animal. Even our mathematics can be read in a manner that expresses development, correspondence and dénouement, each time an equation progresses towards a summation and a resolution. Out of the Dirac Equation of 1928 the positron steps, that ghostly figure of antimatter, some years before anyone could actually confirm its existence experimentally. This equation is surely our greatest modern ghost story; there we found the doppelgänger for everything that had ever existed. And even in scientific writing we employ metaphor, and invent allegories—which are, after all, metaphors in narrative form. We speak of the life and death of stars, though stars don’t actually ‘live’; they are inanimate. But we insist on bestowing our stories upon them, all the same. We bless all things that come our way with narrative structures and plot entanglements. That’s the way we read the world, the manner in which we situate ourselves inside these vast cosmic spaces where we presently find ourselves, whether the end of our endeavours then ends up being called myth or science. We tend to oppose a narrative by confronting it with an alternative narrative; we seldom oppose it by saying, here there can be no narrative at all. If we do say that, we are admitting we’re defeated. And the rest, as Hamlet said, is silence.

Michael Moorcock’s Pyat (together with the manifold variants of his name) is a focus through which the twentieth century recounts some of its more momentous narratives. Pyat is in the largest meaning of the word a narrative device, in the sense in which the Russian Formalists first used that term. The device of the detective in a novel by Raymond Chandler enabled a mobile intelligence unit to explore the heights and depths of society, often on the same afternoon, usually finding both equally wanting. Philip Marlowe is a licensed inquisitor, who probes the murky psychic corners of characters so socially disparate that they could only be connected by a single axis: crime, that vertical shaft through which all social strata can either rise or fall. Up and down the grand social elevator goes our freelance investigator, with his hardboiled banter and his unrelenting scepticism. The identity of the private dick is in truth an embodiment of his function. To be is to do, as the philosopher once expressed it. And what you do often enough turns into what you are; even turns you into what you are.

Now Pyat is the quintessential unreliable narrator: we can’t necessarily believe a word he says at any particular moment. And it is for this reason that Moorcock invented him: how else tell the story of the most mendacious and the most murderous century humanity has yet imposed upon itself (though we might of course be about to excel ourselves there) except through the mouth of someone as egregiously and energeticall

y untrustworthy as the century itself? In Doctor Faustus Thomas Mann has a narrator, Serenus Zeitblom, whose calm humanistic composure provides the tranquil backdrop for the account of fascism and artistic demonism that the book proceeds to expound. The moody tension thus created supplies the narrative dynamic for that remarkable book. Moorcock in this quartet does the precise opposite. The psyche of Pyat is as big, ragged and confusing as the world it describes from the inside, and that is a world of revolution and betrayal, of communism, Nazism and finance capital. Bertolt Brecht once said that the child in Dickens presents us with an empty stage over which the mighty conflicts of the age march back and forth. The child is effectively the elected battleground; the childish consciousness registers with vivid but neutral innocence the dark forces battling all around it. Pyat sometimes seems like that. Although this child, if we are still being Dickensian about it, is more the Horace Skimpole of Bleak House than the true innocent of Oliver Twist. It is the dark distinction of Pyat to match his dreadful age in deadly sins, and deadlier denials of every single one of them. He makes the fornicating immoralists of Henry Miller look like Adam before the Fall. They really do seem to be innocents, as they seek out another cheery domicile between their well-used Parisian sheets.

The unreliable narrator called Pyat stands like a grand, half-ruined structure between ourselves and the facts of history. The facts keep coming at us, but they need to swerve round him as they do so, like starlings flying around a pier at twilight. We know the facts; they constitute the chronicle of the twentieth century. So when Pyat comments upon them, when he speculates for example on the intertwining of Bolshevism and the international Jewish influence, or praises Mussolini or the blacklistings of HUAC, we have enough information as readers to detect an irony where he evidently detects none. Irony, it should be said, is not our hero’s strong point. His remarks about Hitler, Mussolini and Oswald Mosley make that abundantly clear. Our civilisation has been destroyed, he informs us, by the wicked triumvirate of Marx, Freud and Einstein. He is at one here with the book-burners on the streets of Berlin in the 1930s. He would have been a good Index compiler.

An extraordinary kaleidoscope of places and times spins through the consciousness of Pyat. He himself only knows one ethos, and that is survival. He is a rogue Darwinian. The word ‘fit’ when Darwin first used it back in 1859 simply meant ‘best suited for survival in a specified environment’. So what best suits you to survive in an environment where those dedicated to truth and principle have a tendency to perish swiftly? Were Pyat to be simply cynical in this ‘fittedness’ of his, fluently and frankly cynical, then the remarkable books of this quartet would probably be unreadable. If Pyat could own up to his own moral, political and ethnic adaptability, his demonstrable turpitude in living a life (or several), then Moorcock might have pulled off a single short novel with him at the centre, but never something on this scale. No, it is Pyat’s shapeshifting self-identity, his unrelenting belief in his own probity even as we observe him blatantly lying, that keeps us fascinated, as he spouts his racist rants, or sings a paean to the Ku Klux Klan. This is the twentieth century’s own trickster. What intrigues more and more as the quartet progresses is the realisation that the dark century appalls Pyat at least as much as it appalls his readers. He really does want to put things right, though one can only quake at the thought of what kind of world Pyat would in fact have created, had he ever been given plenipotentiary powers.

Pyat is an inventor, in every conceivable sense. He keeps patenting and re-patenting reality, so that it might turn out fit for use at last; his own use. Such fitness for use corresponds to his own fitness for survival. His status as an inventor makes us ponder the curious ambiguity of that term: he was a great inventor, we say, but on the other hand, I’m afraid he invents things. Our facility for re-fashioning the world might be our greatest gift, but it is reciprocally the source of our most pernicious atrocities. Beethoven’s string quartets are invented, surely, but then so is Auschwitz. Pyat stands midway between these two poles of human resourcefulness. He is frequently outraged, but to be fair to him, this is never theatrical outrage. He really is filled with disgust and dread at the world presented to him in all its abominable shoddiness, and he is able to show us that world in such vivid terms that we momentarily share his disgust, even if we feel obliged to question the morphology of his diagnosis, aetiology or prognosis. Pyat’s is a hypnotic voice. Like all genuine psychotics, he makes complete sense of things, even as he leaves financial ruin and moral confusion behind him everywhere. Wherever objective data is lacking, what Coleridge called ‘the shaping spirit of imagination’ supervenes instead. In his monomaniacal world, he is a chameleon king; there is something of Zelig about him. He is of course an engineer, and what he engineers best is reality itself. So it is fitting that he moves in this book from that mighty theatre of social engineering, the Russian Revolution, to the greatest engineering lab for the re-invention of reality the world has ever seen: Hollywood.

So how do we as readers relate to Pyat then? This seems to me the single most troublesome question that these narratives raise. It is possible to enjoy some of Pyat’s rants about the modern world; at times one might even agree. But he is a racist, whose racism involves the self-denial of his own identity. There are times when he does not sound greatly different from the chess champion Bobby Fischer, who also had a certain undeniable genius, together with a determined wish to deny his own Jewishness. In The Ordeal of Gilbert Pinfold Evelyn Waugh created an alter ego whose psychotic, narcotically induced rants were given their convincing specific gravity by Waugh’s own real-life prejudices and detestations. Now, no one who knows anything of Moorcock can suppose that Pyat’s views are in any way his. So why the indulgence of such a retrograde character at such length? Whatever this work is, it is not satire. There is never that consistent fracture between surface meaning and evident underlying intention (what critics call structural irony) that gives satire its coherence. In Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels, we have invention, a great deal of invention, some of it utterly demented, in the Academy at Lagado. But we never doubt where Swift, that avid reader of the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society, stood in regard to all his Projectors. We are entitled, as readers, to ask where Moorcock stands in regard to the old rogue whose voice we are about to hear.

Pyat is intriguing precisely because Moorcock cannot ‘distance’ himself from him. The frame-story device at the beginning, which introduces Moorcock as editor, is low-wattage compared to the rest of the book. The distance that exists between Swift and his Projectors is not in evidence here. Although Moorcock most certainly does not share any of Pyat’s hideous beliefs, he is undoubtedly implicated in his shapeshifting energy, his desperate strategies for survival. Pyat moves swiftly like a mutant virus of the intelligence and the will, and his desperate resourcefulness wins Moorcock’s writerly approbation, even as his political, sexual and financial degradations demand his condemnation. If this is not Swift with his Projectors, it might possibly be Swift in his ‘Digression Upon Madness’ in A Tale of a Tub. Locating that vertiginously adaptable voice—the narrative location from which the disquisition is directed—has been notoriously difficult. Swift appears implicated in the motivations of that voice in a manner that does not allow for any clear demarcations labelled ‘Irony’, ‘Unreliable Narrator’, etc. I would argue that Moorcock’s imaginative energies, his most potent fictional juices, are here involved in a vast complication with the characterisation and multiple voicings of his own egregious persona. It is precisely this complicated involvement with his own narrative creature that holds our attention so vividly, and it is also Moorcock’s daring on of Pyat into further depths of cocaine-fuelled viciousness and deceit that has deeply troubled some commentators. The question might be put this way, in what could be expressed as a tabloid accusation: You made him, after all, so why are you letting him do this, so you might then expound upon his seemingly infinite resourcefulness with such fluent plausibility?

>

That question hovers about the pages that follow, and it is surely an essential part of their frisson. It is precisely Pyat’s fecundity of narrative, his resourcefulness in telling the story of himself in such radically diverse contexts, that makes him so frequently appalling. He never says, like the Nazi officer in Primo Levi’s story of the camps, Hier ist kein warum: here there is no why. He always has a why for any and every question. For him his own narrative, the epic story of his life, is a moral escape route, a rat-line down which war criminals escape to their newly invented identity. There is much in what follows that is genuinely shocking; morally shocking. Pyat, and the stories he endlessly invents to facilitate his survivals, presents us with a morally troubling region. That vertical shaft which connects the rich and the poor in Chandler here connects up the Inferno, Purgatorio and Paradiso of modernity. The paradises, as Baudelaire noted, tend to be artificial. In this quartet no one is straightforwardly saved or damned. Could that be why we still find it so fascinating? Could that be why, in one important sense, this could even be called ‘realist fiction’?

Alan Wall

University of Chester

2012

Introduction

IN THE FOUR and a half years since I finished editing the first volume of Colonel Pyat’s memoirs (Byzantium Endures) my own circumstances changed considerably. I became obsessed with discovering verification for some of Pyat’s claims after I received several letters from people who had known him before the War and whose memories of him were radically different. As a result my travels took me in his tracks and at one time it seemed I had condemned myself to continue his wanderings where he had left off in 1940. A retired Turkish bimbashi, one of Kemal’s revolutionary nationalists in 1920, assured me Pyat was an American renegade, a Zionist working for the British. Two vigorous octogenarians in Rome insisted he was a Polish Communist who planned to infiltrate the early fascist movement. In Paris it was generally agreed he was Russian, possibly a Jew, associated more with the criminal world than with the political underground. Not everyone knew him as Pyat (Piat or Pyate are variations). To several Berliners I met he was either Peterson or Pallenberg, but they readily confirmed that he was a scientist, an engineer. One German lady, presently living in Oxford, a Buchenwald survivor, was amused by my asking if she thought Pyat as successful as he claimed. She knew of at least one brilliantly successful invention, she said. Then she laughed and refused to continue. She had periods of mental instability.