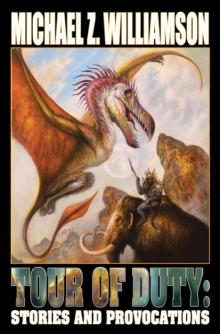

Tour of Duty: Stories and Provocation

Michael Z. Williamson

Baen Books by

Michael Z. Williamson

Freehold

Contact with Chaos

The Weapon

Rogue

Better to Beg Forgiveness . . .

Do Unto Others . . .

When Diplomacy Fails . . .

The Hero (with John Ringo)

Tour of Duty

TOUR OF DUTY

This is a work of fiction. All the characters and events portrayed in this book

are fictional, and any resemblance to real people or incidents is purely coincidental.

Copyright © 2013 by Michael Z. Williamson

“Naught But Duty,” © December 2005 by Michael Z. Williamson, Crossroads and Other Tales of Valdemar, DAW. “The Humans Called It Duty,” © March 2007 by Michael Z. Williamson, Future Weapons of War, Baen Books. “The Sword Dancer,” © December 2008 by Michael Z. Williamson, Moving Targets and Other Tales of Valdemar, DAW. “Wounded Bird,” © December 2009 by Michael Z. Williamson, Changing the World: All New Tales of Valdemar. “The Price,” © May 2010 by Michael Z. Williamson, Citizens, Baen Books. “The Groom’s Price,” © December 2010 by Michael Z. Williamson, Finding the Way and Other Tales of Valdemar, DAW. “Heads You Lose,” © Janet Morris, August 2011, Lawyers in Hell, Kerlak Publishing, reprinted by permission. “The Brute Force Approach,” © August 2011 by Michael Z. Williamson, Baen.com, Baen Books. “The Bride’s Task,” © 2011 December by Michael Z. Williamson, Under the Vale and Other Tales of Valdemar, DAW. “A Hard Day at the Office,” Rogues in Hell, © July 2012 Janet Morris, Perseid Publishing, reprinted with permission. “Desert Blues,” © August 2013 by Michael Z. Williamson. “One Night in Baghdad,” © 2006 by Michael Z. Williamson. Appeared in a slightly different form on michaelzwilliamson.com. “Port Call,” © January 2003 by Michael Z. Williamson, michaelzwilliamson.com. “April Fool,” © April 2006 by Michael Z. Williamson and Brad Linaweaver, Locus Magazine Online. Crazy Einar’s articles first appearance The Pennsic Independent at the Pennsic War between 1999 and 2005. All are © August 2013 by Michael Z. Williamson. “My True Encounters With the Indianapolis Police Department,” © August 2013 by Michael Z. Williamson. “Inappropriate Cocktails,” © August 2013 by Michael Z. Williamson. “On Reparations Generally, for the Descendents of People Long Departed,” © 2003 by Michael Z. Williamson, michaelzwilliamson.com. “The Manly Way To Cook Meat,” © October 2007 by Michael Z. Williamson, ManlyExcellence.com. “The Ten Manliest Firearms ,” © 2007 by Michael Z. Williamson, ManlyExcellence.com. “Ten More Manly Firearms,” © 2008 by Michael Z. Williamson, ManlyExcellence.com. “The Mosin Nagant,” © July 2009 by Michael Z. Williamson, ManlyExcellence.com.

All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book or portions thereof in any form.

A Baen Book

Baen Publishing Enterprises

P.O. Box 1403

Riverdale, NY 10471

www.baen.com

ISBN: 978-1-4516-3905-6

Cover art by Bob Eggleton

First Baen printing, August 2013

Distributed by Simon & Schuster

1230 Avenue of the Americas

New York, NY 10020

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Williamson, Michael Z.

Tour of duty / Michael Z. Williamson.

pages cm

"A Baen Book."

ISBN 978-1-4516-3905-6 (trade pb)

1. Mercenary troops--Fiction. 2. Undercover operations--Fiction. I. Title.

PS3623.I573T68 2013

813'.6--dc23

2013010546

Printed in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Dedication

For my brother and sister veterans of OEF/OIF.

With respect.

How I Got This Job

As I sit here finishing this collection and sipping fine Scotch, I still wonder, “How the hell did I get here?”

I was born in the UK, to a Scottish father and English mother. They got married, so I’m Scottish. If Scotland ever does declare independence, I will gain yet another passport.

I remember growing up middle class in the UK. My father had a motorcycle, and eventually a car, while he alternated electrical work and school. My mother waited tables evenings. We had a “flat” with no heat, and a transistor radio. Lunch for me was usually a boiled egg or a slice of bread with jam. In 1969 we got a black and white TV so we could watch the moon landing. Since my father was an electrical engineer, he re-programmed the set and we got four channels, though BBC1 and -2 usually showed the same thing. I remember the occasional Doctor Who, Tom and Jerry, and yes, Sesame Street.

Eventually we moved to a real house (well, a duplex), with plumbing. We were lucky. The row houses behind us had bathrooms tacked onto the back, with pipes running up to deliver water, and I believe the sewage dumped down into a semi-open system. They were a hundred years old and predated modern plumbing.

Every day, my mother would walk me the half mile to school, and pick me up afterward. The school toilets were also outside. After three years, the school built a brand new bathroom, still outdoors. However, we no longer had to urinate in a gutter or crap in a hole. When school wasn’t in session, my mother would take my hand and, with my sister in a pram, we’d walk most of a mile to the town market.

Now, in early 1970s Britain, she had to argue with the grocer, who wanted to get rid of the oldest food first for the same price as the fresh stuff. Then she’d load it in a small cart and pram in front, pulling that behind, or having me push one, we crossed a couple of four-lane roads to walk home.

We moved to Canada, because the mid’-70s economic climate in the UK didn’t look promising. My parents were young, but they were correct.

My father went ahead of us, secured a job, and sent for us. As we departed England, there was a bomb scare on our aircraft. It only took a few minutes to resolve, but I’ll always remember it.

Upon arriving in a hot, sunny Toronto, I was loaded into a Pontiac Parisienne, a Bonneville with a Canadian accent, where my feet didn’t even reach off the seat, and there was a radio in the car. THERE WAS A RADIO IN THE CAR! I was driven to an A&P, where there was a hundred feet of fresh produce. It was really odd, because there was no glass and no grocers. You could take whatever you wanted and put it in a bag, then they’d load it all into the car for you. You could just leave what didn’t look fresh, and they’d do something with it. I was sure they didn’t waste it, though.

You’ll see hints of this in my writing. Do not ever make the mistake of thinking that a shared language equals a shared culture. Certainly, there are likely to be more similarities than for people who don’t share a language, but even common words can change. For example, the first day of work, my father asked the office’s secretary for a “rubber,” by which he meant “eraser.” In Canada in the 1970s, this was easily understood and corrected. Use that term in America today, and there could be legal repercussions and EEO action.

I liked Canada, mostly. The bullies were worse than in the UK or the U.S. and traveled in packs. That surprises people who want to believe all Canadians are polite and kind. I have two words for you: “Ice hockey.”

It was quickly determined that my British education at the hands of the Anglican Church put me far ahead of my peers. I could write in cursive, do long division, basic wood crafting and needlepoint, and had a good grasp of both grammar and science. That paid off later, of course. At the time, I was placed a grade ahead.

Most Canuckians in Mississauga, Ontario, are apartment dwellers, though the apartments have a lot of nice features—pools, squash and tenn

is courts, underground parking. It wasn’t a huge change for me in that regard—the apartment was at least as big as the house in England, and there were lots of kids to play with. TV was easy—we could reach Toronto and Buffalo, and get Sesame Street in English, French and Spanish, and about thirty channels. Actually, I could have learned a lot of languages. Twenty-seven of thirty students in my fourth grade class were immigrants.

Then I found out about something called “Trick or Treat.” Rather than wear sheets and papier maché masks while munching treacle around a fire on the commons, it was encouraged to visit other apartments asking for candy. When you realize these apartments were 13-25 floors of 15-40 apartments per floor, with five buildings within easy walking distance, I still don’t remember how I managed to cover them in only a few hours, but I do remember entire pillowcases (plural) full of loot.

I did take up skating, and ice hockey, and street hockey, and gym hockey, having an entire bag of sticks of different types at different lengths for skates vs. shoes, and both left and right handed.

It was in Canada where I started writing my first book. I’d been studying up on rockets (that moon landing was still with me), writing text and sketching pictures of fuel systems, gantries, rocket staging, telemetry charts. I had dozens of pages finished, all done with marker and ruler.

Canada wasn’t quite what we were looking for, apparently. A few years later, my father found another job, and we wound up moving to the U.S. and settling in Central Ohio, where it was explained to me that we should have two cars, since we had two adults in the house. A friend’s parents were unable to properly discipline their son, because if they sent him to his room, he just watched TV there instead. Same language, different culture.

The teachers frowned at the complication I offered, and tossed me into class. That first day, I took an American history quiz and aced it. They were surprised. I was surprised to find it was specified as “American” history, and more so to find that the name was redundant, as they didn’t really teach other nations’ histories.

I could have skipped another grade, but I was already far ahead, skinny, and facing maturity issues. We all decided I should stay where I was.

There were bullies in Ohio, too. I was a small kid, but I always fought back, and eventually got better at it. At first I got the crap beat out of me, and I really didn’t know how to fight back. By the time high school rolled around I was a pretty decent brawler, but for some reason—probably being skinny, too smart for my own good, and mouthy—kids kept trying to beat on me. A few of us came to terms. The rest seem to have wound up the way most congenital bullies do—as not much of anything.

There was another turning point about then. It seems our immigration attorney was sneaky. He never actually put in writing what he was advising us to do by phone. We’d gotten a temporary visa for a year, moved to the U.S., bought a house, settled in, and applied for a permanent visa.

The temporary visa expired. That left us in limbo. You can’t leave the country and reenter without a visa, so we couldn’t visit family. We had no legal status at all, though we were still paying taxes. But you know those silly things kids do, like shoplifting, breaking curfew, et cetera? If I’d been caught doing stuff like that, my entire family could have been deported, our future stricken. In theory, it takes a pattern of such behavior, and a few misdemeanors aren’t an issue. It has to be a crime of “moral turpitude.” But legal immigrant teens are very cognizant of this standard. And, once the visa expired, we had no status. Any slip could have ended the trip. I sympathize with a lot of “illegal” aliens, because it’s very easy to be illegal even without intent. I know of several variations that friends have slipped into by accident.

Three years later, we finally got in to see an immigration officer. She looked at our papers, considered, looked at us, and said, “The problem is that what you did is illegal.” (It is legal now. It was not then.)

Even for a teenager, that’s a pretty heavy blow. By getting a temporary visa, we’d stated an intent to leave. Applying for a permanent visa contradicted that. And no, good intentions make no difference to the law in a case like this. All that matters is your papers. The easiest thing for this agent to do was to stamp a sheet and send us back to the country before the country we’d left, with a bar on reentry to the U.S. for ten years, and sucks to be you. We’d have had a few months, but would have had to sell the house, uproot, see if Canada would take us back as residents, or else relocate back to the UK again, at the height of the late 1970s troubles, and re-adapt to a culture we’d left behind.

The hardest thing for her to do was for her to write a letter to her superiors explaining that she believed we had honest intent and faulty advice, and that we should be granted the opportunity to apply for permanent visas.

She did this.

Ma’am, whoever you were, THANK YOU. I can never repay that kindness, that very nonbureaucratic thoughtfulness.

We were allowed to become American Permanent Residents, and don’t ever lose that green card.

My parents divorced when I was fifteen, and my mother, sister and I were on tight rations while my mother sold real estate and tried to find something more lucrative. My paper route money often went toward food. At sixteen I started cleaning and detailing cars for a few bucks.

Adulthood is a turning point for many people, and it was for me, but with a difference: Our citizenship hearings came up. I was barely an adult, still in high school, and had to be debriefed.

As immigrant nonrefugees, the bar we had is somewhat higher than it is for native borns or those seeking asylum. For example, proof of literacy is required. One couldn’t belong to any subversive or communist group, must not have a criminal background, must demonstrate “adequate knowledge” of U.S. history and government, and, yes, much of this applies to teenagers as well as adults. That last is the cutout—if they’re sure you’re some kind of enemy plant, they can ask who the fifteenth vice president was (Hannibal Hamlin) and when you don’t know, they can boot you.

It was ironic that the kid from England was required to write on the form, “I can speak, read and write the English language.”

In the meantime, I realized I didn’t have the focus for college, and needed out of the house. I didn’t get along well with either parent, and needed something. The Army recruiter probably could have hooked me if he’d shown more perseverance, but the Air Force recruiter won out. I took the ASVAB test—Armed Services Vocational Aptitude Battery—and demolished it, as I had the ACT and SAT. I got 99th percentile across the board. I showed up at the Columbus Military Entrance and Processing Station and was offered a huge list of jobs, including things like “computer security,” which were in their infancy. I gleefully selected a dozen choices.

Then the counselor said, “Wait, your paperwork indicates” something negative. “Are you a felon?”

“Uh . . . no . . . ”

It turns out there’d been some questionable security clearances that had allowed spies into various places. Immigrants were held to the same standards as felons, until naturalization was complete, and mine wasn’t.

That list of a hundred jobs shrank to a dozen, including things like “Plumber.” Now, plumbing is a worthy profession. But it wasn’t as glamorous as what I’d been shown moments before.

I wound up in an engineering specialty that changed over time, being largely a glamorized air-conditioning and cryogenic plant mechanic on the peacetime side, though it did include some weapons and vehicle training for deployment purposes.

Sometimes, you take what you can get. It worked out in the end.

I entered the Delayed Enlistment Program, and prepared to finish school. I finished, I graduated, and it was very much anticlimactic. I wasn’t any smarter, and richer, or any more employable.

Then the second immigration hearing came up, the important one. We scraped enough money to buy me a suit, and my mother and younger sister wore church-worthy dresses.

This time, the waiting roo

m was full of dozens of people. There were Czechs, Chinese, Argentines, Rhodesians, Malians, a couple of other Brits and others we never met. I have never felt what I felt in that room. None of us had anything in common, but we all had one thing in common. We talked about our former homes, the differences, the opportunities. Everyone was dressed for the occasion.

When my name was called, the immigration official required me to confirm previous questions. He asked, “Since your last hearing, have you joined or belonged to any organizations other than the Boy Scouts and Civil Air Patrol?”

“Yes,” I answered.

He looked up at me, a bit surprised, because this was supposed to be largely a formality at this point.

“Which organization?”

“The U.S. Air Force.”

It took him a moment to process that, then he grinned hugely and said, “So you’re definitely here for the long haul.”

“Yes, sir, I am.”

He had me sign the papers, then he signed.

A while later, all of us together wound up in a courtroom, in seated rows, silently and politely awaiting our Immigration Judge.

The judge came in, very cordially, noted this was the most enjoyable part of his job, and he was proud to see us. He even knew which countries some of us were from, which was both very thoughtful, and very professional.

Then we raised our hands, and he administered the Naturalization Oath. There was a quiet cheer, and we all shook hands and patted each other on the back.

Fifty people entered that courtroom. Fifty Americans came out. If you are an immigrant, you understand. If not, I cannot explain it to you. At that moment, after a decade, I was once again, and at last, home.

I still have that suit, by the way. There is no way my chest would fit in that skinny jacket anymore, nor my arms, and to be fair, the waist is at least three inches too small. But that suit is mine.