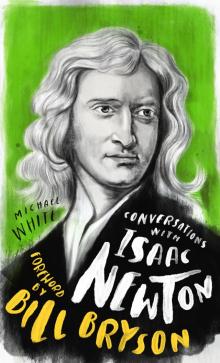

Conversations With Isaac Newton

Michael White

Note to the Reader: This book is divided into two parts: a biographical essay that provides a concise overview of Newton’s life and achievements and a fictional dialogue based on rigorous research, incorporating Newton’s actual spoken or written words, whenever possible, along with rigorously research biographical interpretations of his various views and positions.

Learn about key figures in science, spirituality, art and literature through revealing dialogues based on established fact. Written by a fantastic collection of authors and foreword writers gathered together to delve into the lives and achievements of some of the world’s greatest historical figures, this series is perfect for anyone looking for a quick and accessible introduction to the subject.

OTHER TITLES IN THE SERIES

Published

Conversations with JFK by Michael O’Brien;

Foreword by Gore Vidal

Conversations with Oscar Wilde by Merlin Holland;

Foreword by Simon Callow

Conversations with Casanova by Derek Parker;

Foreword by Dita Von Teese

Conversations with Buddha by Joan Duncan Oliver;

Foreword by Annie Lennox

Conversations with Dickens by Paul Schlicke;

Foreword by Peter Ackroyd

Conversations with Galileo by William Shea;

Foreword by Dava Sobel

Forthcoming

Conversations with Einstein by Carlos I. Calle;

Foreword by Sir Roger Penrose

Conversations with Freud by D.M. Thomas;

Foreword by Edward de Bono

Originally published under the title Coffee with Isaac Newton 2008

This edition first published in the UK and USA 2020 by

Watkins, an imprint of Watkins Media Limited

Unit 11, Shepperton House

89–93 Shepperton Road

London

N1 3DF

[email protected]

Design and typography copyright © Watkins Media Limited 2020

Text copyright © Michael White 2008, 2020

Foreword copyright © Bill Bryson 2008, 2020

Michael White has asserted his right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 to be identified as the author of this work.

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, without prior permission in writing from the Publishers.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Typeset by JCS Publishing Services Ltd

Printed and bound by TJ International Ltd, Padstow, Cornwall

A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN: 978-1-78678-383-7

www.watkinspublishing.com

Publisher’s note: The interviews in this book are purely fictional, while having a solid basis in biographical fact. They take place between a fictionalized Isaac Newton and an imaginary interviewer.

CONTENTS

Foreword by Bill Bryson

Introduction

Isaac Newton (1642–1727): His Life in Short

Now Let’s Start Talking …

The Wounds of Childhood

Inspirations

Initiation

Bitter Feuds

A Faith Apart

The Light in the Crucible

The Secrets of the Ancients

Gravitation and Motion

On the Nature of Light

Making a Quality Telescope

A Fresh Start

London Life

The Royal Society

A Remarkable Legacy

Further Reading

FOREWORD BY BILL BRYSON

In a basement room of the Royal Society in London, Joanna Corden, the society’s friendly archivist, opens a white box and gently lifts out one of that learned institution’s most venerated relics: the death mask of Isaac Newton, made on the evening of his death in 1727.

It ought to be a thrilling moment – this is, after all, the closest we can come to the physical presence of the most fertile and intriguing mind of its age – and yet, as Corden had promised, there is something oddly disappointing in Newton’s impassive visage. You don’t expect a death mask to be terribly expressive, of course, but this one has an almost determined blankness to it.

“Even in death,” notes Corden, “he didn’t give much away.”

We stare respectfully at the mask for half a minute, then she returns it to the box and replaces the lid, and I realize that already I’m beginning to forget what he looked like.

Perhaps no great figure in history has been harder to know and understand than Isaac Newton. Indeed he is doubly unknowable – first because of the complexity of so much of his science and second because of the secrecy and very real oddness with which he conducted so much of his life. Here is a man who spent three decades as an academic hermit in Cambridge, as withdrawn from worldly affairs as one could be, but then in late middle age became a fêted public figure and comparative gadfly in London. He could unpick the most fundamental secrets of the universe, yet was equally devoted to alchemy and wild religious surmise. He was prepared to invest years in embittered fights over credit for the priority for discoveries, yet cared so little for conventional adulation that his most extraordinary findings were sometimes kept locked away for decades. Here is, in short, a man who was almost wilfully unknowable.

Corden brings out another of the Society’s treasures – a small reflecting telescope made by Newton himself in 1669. It is only six inches long but exquisitely made. Newton ground the glass himself, designed the swivelling socket, turned the wood with his own hand. In its time this was an absolute technological marvel, but it is also a thing of lustrous beauty. The man who made this instrument had sensitivity and soul as well as scientific genius.

“It’s strange, isn’t it,” says Corden, reading my thoughts, “that you can feel more in his presence from one of his instruments than from his own death mask.”

There really never was a more private man. So how lucky we are to have this volume in which Michael White deftly brings this impossible character to life, and makes his frequent wild actions and wayward notions seem almost reasonable. Even better, White conveys to us Newton’s most challenging scientific concepts in terms that render them logical and wondrously, instantly comprehensible, and in so doing he fully captures the excitement, satisfaction and very real beauty of scientific discovery.

So prepare yourself for an unusual treat. You are about to enter one of the greatest minds in history.

INTRODUCTION

Isaac Newton was a man who transcended the age in which he lived, and in terms of his influence on the modern world, he is without peer. He formulated the theory of gravity, devised a radically new theory of light and created a calculus that would revolutionize mathematics. His most famous work, Principia Mathematica, is arguably the most important scientific book ever published: it explains his theory of matter in motion, which, a generation after his death, sparked the Industrial Revolution.

Newton achieved a phenomenal amount in one lifetime, and he really had several careers. He was a scientist and a mathematician who later became an administrator, serving first as a Member of Parliament, then as master of the Royal Mint. Late in life, he turned the Royal Society from a dilettante’s club into an eminent scientific organization. Although he was extremely pious and a devout Christian, he was thoroughly unorthodox in his religious beliefs and spent much time exploring aspects of arcane knowledge, including the taboo subject of the occult.

The premise of this book is a conversation between myself and Isaac Newton. The setting is left to the i

magination of the reader, but we may assume that the interview takes place at the very end of Newton’s life when he is able to reflect on his achievements and the key events of his time.

Newton was a disagreeable man who was often unpleasant and antisocial; consequently, he had few friends. He relied entirely upon his own counsel and one had to work hard to earn his respect. He might have been resistant to a conversation such as the one here, but equally, he liked others to know of his brilliance, a commodity he possessed in abundance.

ISAAC NEWTON (1642–1727)

HIS LIFE IN SHORT

The iconic image of Isaac Newton is that of a young man in 17th-century attire, musing on the nature of the universe while sitting under the hanging branches of a tree. Serendipitously, an apple falls on his head, and in this inspired moment his thoughts gel and his genius releases a flood of ideas that bring forth the theory of universal gravitation and, with it, a law to explain the action of gravity.

This is a romantic notion, and one probably based only vaguely on the truth. Certainly there were apple trees in the garden of his mother’s home in Woolsthorpe (the house in which he was born). Those trees are still there and it is likely Isaac Newton did indeed sit under them from time to time. He visited his mother during the summer of 1665, fleeing Cambridge as plague spread beyond London. And this was also the summer in which he began to get somewhere with his thinking about gravitation. But the idea that Newton saw the whole complex array of his theory in the very moment the apple was supposed to have fallen is overly simplistic and almost certainly a glamorous invention, one probably contrived by Newton himself to obfuscate the real story.

Isaac Newton was born on Christmas Day 1642 into a relatively prosperous family from the village of Woolsthorpe in Lincolnshire. His father, also named Isaac, was an illiterate farmer and landowner who married Hannah Ayscough, a local girl from a socially superior family which had recently lost most of its lands and capital through a series of bad investments.

At this time, England was in the grip of the Civil War. That summer, the earliest skirmishes in the conflict between rival political and religious groups had begun to escalate into a savage bloodletting in which families were torn apart over ideological differences, and often brothers found themselves on opposing sides. On a superficial level, the Civil War was a clash between those who supported the monarchy (the Cavaliers) and those who wanted to depose King Charles I (the Roundheads); but it was also a war between Catholics and Protestants, a conflict that had its roots in the schism with Rome precipitated by Henry VIII almost a century earlier. Newton’s family were staunchly Protestant and Charles I was strongly pro-Catholic, so it is most likely the family would have supported the Roundhead cause in the war.

Isaac Newton’s father died before his son was born, and the baby, who arrived two months premature, was said to have been so small he could fit into a quart pot. Indeed, he was not expected to live long. When the boy was three years old, his mother, Hannah, remarried. Her new husband was Reverend Barnabas Smith, a local vicar who did not want Isaac living with them. So the child was brought up by his grandparents at the family home in Woolsthorpe.

This event traumatized Newton and acted as a powerful force in shaping his character. He loathed his stepfather and wrote in his diary that he wanted to kill the man. Throughout his schooldays he remained detached and introverted. He did not do particularly well at school until about the age of 14 when he was noticed by his headmaster, Henry Stokes, who encouraged him and boosted his confidence.

While he was at the King’s School in Grantham, Newton lived for a while with a family called the Clarks, who ran an apothecary. Mr Clark’s brother, Dr Joseph Clark, had been a successful academic at Cambridge University but had died young, leaving behind an impressive library of arcane texts which were stored in a backroom behind the shop. The collection included radical books by Galileo, Giordano Bruno and René Descartes, and Newton worked his way through the entire library before being accepted into Trinity College, Cambridge, in 1661.

Soon after going up to Cambridge, Newton came under the influence of older scholars who saw something in him and encouraged him. Most important among these were the Cambridge Fellows Humphrey Babington, Henry More and Isaac Barrow.

From 1664 Newton conducted experiments to discover the true nature and character of light. He based his early ideas on those of Descartes but soon outstripped him in analysing the way light behaved under different conditions. He formulated mathematical descriptions of reflection, refraction and diffusion, explained the nature of colour and demonstrated how a spectrum could be formed and manipulated. He recorded his findings but kept them to himself because, even then as a young student, he was suspicious of the intentions of others and was paranoid that his ideas might be stolen if he attempted to publish anything.

The year between the summers of 1665 and 1666 has been called Newton’s annus mirabilis, and with good reason. During this astonishing twelve-month period he laid the mathematical foundations for his theory of gravity and articulated his three laws of motion, which formed the basis of the new scientific discipline of mechanics. He also developed further his ideas about optical phenomena, began building his first telescopes and devised his calculus and another important mathematical tool called the binomial theorem.

Isaac Newton was made a Fellow of Trinity College in 1668, succeeding his mentor Isaac Barrow to become the second Lucasian Professor of Mathematics at Cambridge (the seat held more than 300 years later by Stephen Hawking). He was only 27, the youngest man ever to hold the chair. By the time he was 30 he had become a Fellow of the Royal Society.

The seeds of Newton’s greatest contributions to science were planted early in his career, but these really were only seeds. His theory of universal gravitation was a strikingly original concept to explain one of the great forces at work in the universe, the force that keeps the planets in their orbits and the stars and galaxies in their courses. It did not come to him in one miraculous moment, but took almost 20 years to evolve and was the result of many influences, especially mathematics and alchemy, countless scientific experiments he conducted in his rooms and a multitude of observations he had made of planets and comets using his telescope. The theory did not fully take shape until he wrote his great book, Principia Mathematica, which he began in 1684 and saw published in 1687. Today, this is regarded as probably the most influential scientific treatise ever written.

The first major influence on the theory of universal gravitation was mathematics. Isaac Newton was a supreme mathematician, who was, by the age of 24, the most advanced of his time. He was also a versatile natural philosopher, and long before he was made a professor he had absorbed the entire canon of science up to his time. By the plague year of 1665, he had studied in detail the work of all the major mathematicians of the era, including John Wallis, Robert Boyle and René Descartes, and had made his own original contributions. For example, he took Descartes’s concept of Cartesian coordinates (the graphical representation of points between axes x, y and z), which the Frenchman described in his Discourse on Method (1637), and produced a mathematical interpretation of Galileo’s ideas of acceleration. He also illustrated how his own calculus could be used to solve practical problems.

Around the same time, Newton devised a generalized version of an algebraic technique called the binomial theorem, which allows mathematicians to calculate the power of sums (the value of any two numbers x and y added together and taken to any power n). It is believed that a limited form of the theorem (for small values of n such as squares and cubes) was known to the Indian mathematician Pingala during the 3rd century BC, but Newton was the first to create a general theorem for any value of n.

Using his mathematical talents he began to understand that gravity was responsible for keeping the planets in motion and suggested a mathematical relationship linking the distance between two bodies (such as planets) and the force of gravity between them – a relationship he called the inverse square

law. This was a great accomplishment, but neither Newton nor anyone else at the time could understand how this force actually operated.

The second influence to guide Newton along the road to his theory of universal gravitation was alchemy and the occult tradition. During the 17th century, the idea that an object could influence the movement of another without actually touching it was unimaginable. Such behaviour is now called “action-at-a-distance” and we take it for granted, but in Newton’s day it was seen as magical, an occult property. But thanks to his experiments in alchemy, Newton could approach gravity with a more open mind than most of his peers.

Newton was never interested in studying alchemy for personal gain or for making gold. His sole purpose was to find what he believed were hidden basic laws that governed the universe. He was a Puritan who believed in the idea of God’s “Word” and God’s “Works”. He was devoted to the teachings of the Bible – God’s “Word” – and he believed that it was his duty to unravel the puzzle of life, to investigate everything there was to know about the world; in other words, to study God’s “Works”.

During Newton’s lifetime, alchemy was a crime, punishable by death. Not only that, but any hint that he was experimenting with alchemy would have destroyed his academic reputation. But this belies the fact that Newton actually spent far more time on alchemical research than he did on orthodox scientific practice. When he died in 1727, Newton was discovered to have owned the largest library of occult literature ever collected; he had himself written more than a million words on the subject, along with at least a million more words analysing the Old Testament and interpretations of the prophets.

Newton began investigating alchemy in 1669. He travelled to London to buy forbidden books from fellow alchemists and carried out his secret experiments far from the prying eyes of the authorities and his rivals within the scientific community. His earliest experiments were very basic, but after reading everything he could about the art, he soon pushed alchemy further than any of his predecessors. Unlike them, he approached experiments logically and with great precision, meticulously writing up what he had discovered.