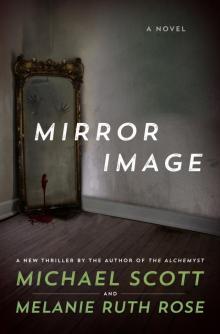

Mirror Image

Michael Scott

Begin Reading

Table of Contents

About the Authors

Copyright Page

Thank you for buying this

Tom Doherty Associates ebook.

To receive special offers, bonus content,

and info on new releases and other great reads,

sign up for our newsletters.

Or visit us online at

us.macmillan.com/newslettersignup

For email updates on the author, click here.

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you without Digital Rights Management software (DRM) applied so that you can enjoy reading it on your personal devices. This e-book is for your personal use only. You may not print or post this e-book, or make this e-book publicly available in any way. You may not copy, reproduce, or upload this e-book, other than to read it on one of your personal devices.

Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the author’s copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

FOR BARRY

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to thank the many people who helped usher this book to publication: Tom Doherty, Bob Gleason, and Elayne Becker at Tor for everything!

The dynamic duo, Barry Krost and Steve Troha.

Melanie would like to especially thank: Matt, Shelley, Sue, Paul, and Jaffee for their encouragement.

And for Jill who showed me nothing but love, support, and inspiration in my new journey.

1

THE MIRROR stood seven foot tall, four foot wide, the glass dirty and speckled, warped so that the images it showed were slightly distorted and blurred. It was quite grotesque.

And Jonathan Frazer knew he had to have it.

He stood at the back of the small crowd in the foul-smelling auction room and waited impatiently while the bored auctioneer made his way through the catalogue of the Property of a Gentleman.

“Lot 66, a French Gendarme’s Side Arm Saw Sword, with a double edged steel blade, bronze handle and cross guards, complete with leather scabbard. The blade shows some wear…”

Although it was only just after one in the afternoon, Jonathan Frazer was tired. He’d been in England a week, but was still jet-lagged, a feeling not helped by London’s miserable November weather which sapped his energy and left him achy and vaguely fluey. He had spent the last few days doing the rounds of the auction houses in London but had come away empty-handed. He’d been tempted to skip the quirky auction house on Lots Road in Chelsea but, like every dealer he knew, there was always the fear that the find of a lifetime was waiting in the auction you never attended. Thanksgiving, and then Christmas, were just round the corner and he needed to find some unique items. In the next few weeks Hollywood’s A-listers or, more likely, their personal assistants would go looking for expensive presents for the friends they never saw.

The auction had already started when Jonathan stepped into the shadowy interior of the auction room and began to wander around amongst the larger objects piled up at the back of the room. Furniture, none of it interesting, was strewn about the premises and, at the other end of the room, a motley assortment of people faced an elderly man. The auctioneer’s singsong chant drifted through the room. Frazer shook his head slightly. He hadn’t been expecting to find anything: the really good stuff was usually traded amongst the dealers and collectors and rarely reached the general public. Much of what was here was trash, or the condition was so poor as to render them worthless. But one man’s trash was another’s treasure.

“Lot 68, a gentleman’s half-hunter pocket watch … in need of repair…”

A sliver of silver light at the very back of the room caught his attention and he turned, squinting into the gloom. It took him a moment to make out the shape: there was a mirror behind a wood-wormed wardrobe and an early Edwardian dresser.

He squeezed between the wardrobe and the dresser, initially attracted to the sheer size of the glass. He was six foot tall and it was at least a foot taller than he was. He spread his arms, judging the width from experience: it was at least four foot wide. There was a surprisingly plain wooden frame surrounding it, complete with brass clips for securing it to a wall, although it was now mounted on an ornate stand. The stand was a later addition, he decided.

Jonathan Frazer ran his hand down the mirror, drawing long streaks on the glass; it was filthy, covered with a greasy layer of grime. He rubbed a tissue around in a circle at about head height and peered into it, but, with the dimness of the auction room and the dirt encrusted onto the glass, he could barely make out his own reflection. He licked his finger and rubbed it against the mirror, his breath catching when he felt its chill against his flesh, but even that made no impression on the grime.

Without examining the back of the mirror he had no way of accurately dating it, but, considering the slightly bluish tinge to the glass, the perceptible distortion around the perimeter and the curious beveling in towards the center, it was certainly old, seventeenth century, possibly earlier.

“Lot 69, a large antique wooden-framed mirror, approximately seven feet tall by four feet wide. An imposing piece.”

Jonathan Frazer took a deep breath, suddenly glad he was wearing jeans and a long sleeved sweatshirt and not his regular suit. He cast an experienced eye over the small crowd: he couldn’t spot any obvious dealer-types. He hoped anyone looking at him would assume he was just another guy in off the street looking for a bargain.

“Now who will open the bidding at eight hundred pounds?”

Frazer could hardly believe his ears. The mirror was worth at least ten times that. But he kept his head down, not looking at the auctioneer, showing no interest.

“Seven hundred and fifty then. Come along ladies and gentlemen; it’s here to be cleared. Seven hundred and fifty for a fine piece of glass like that. A handsome piece in any house.”

“You’d need a bloody big house for that, mate,” someone quipped in a cockney accent.

The auctioneer smiled. “Five hundred pounds, ladies and gentlemen. Five hundred pounds, or I’ll have to pass.”

Frazer looked up and caught the auctioneer’s eye. He raised his left hand and spread his fingers wide.

The auctioneer frowned, then nodded slightly. “Five hundred pounds is bid. Any advance on five hundred pounds? Come along ladies and gentlemen, this is a real bargain. Any advance on five hundred pounds?”

No one moved.

“Fair warning at five hundred pounds. Five hundred. Going once, going twice…” The auctioneer slammed his gavel on the lectern. “Sold!” He looked in Frazer’s direction and nodded. “Now moving on to Lot 70…”

A young man wearing blue overalls made his way through the crowd and handed Frazer a slip to fill in.

“Can you ship it?”

“We can, of course, sir, shipping is extra.”

“Of course.” Frazer handed across his business card. “To this address.”

The young man turned it over. “Frazer Interiors. In Los Angeles. I remember you, sir. We shipped you those carved Chinese lion heads.”

“You’ve a good memory.”

“I had to wrap them and ship them. I’ve never forgotten them. It’s been a while since we’ve seen you.”

“I know. And you’re my last call of the day.” Frazer glanced back at the mirror. “My lucky day.”

The young man smiled. “You got a real bargain, Mr. Frazer. You’re obviously the right man in the right place at the right time.”

2

“IT’S QUITE something.” Tony Farren ran his hand appreciatively down the length of the glass. “The frame’s horrific, but we’ll see if we can do something about that.”

Jonathan Frazer crouched down in front of the enormous mirror, pointing to the black speckling that ran around its edges. “Let’s see what we can do about these, too, OK?”

Tony nodded. “That’ll be no problem.”

Jonathan stood up and brushed off his hands. “What do you think?”

The two men were standing in the converted garage-workshop at the back of Frazer’s home in the Hollywood Hills that held the overflow from the shop. Tony Farren tucked his hands into his jean pockets. He had been with the Frazer family since James Frazer, Jonathan’s father, opened an antiques business in Hollywood in the mid-sixties. When Jonathan inherited the business and turned Frazer Antiques & Curios into Frazer Interiors, selling mid-century furniture mixed with carefully selected antique pieces, Tony stayed on. Small, stout, and completely bald, his knowledge of antiques was phenomenal. When Jonathan was a boy, he spent most of his summers in the crowded, musty converted garage at his parents’ home in Los Feliz watching, fascinated, as Tony worked and talked. Jonathan always claimed that everything he knew about antiques he learned from Tony Farren.

“It’s a fine piece,” Tony said eventually. “Very fine.”

“Can you put a value on it for me?” Jonathan smiled. Very fine was high praise indeed.

Farren ran his hands over the glass, and then used a small flashlight to throw a light onto the mirror. He repeated the procedure with the wooden frame, and then moved behind the tall mirror to examine the back. He ducked out from behind it, peering over his horn-rimmed glasses. “It’s an interesting piece, no mistake about that. The glass is Venetian, possibly late fourteenth, early fifteenth century, although it’s very difficult to say. Could be even earlier for all I know. The frame looks early sixteenth century, it’s in the style certainly, although the wood looks older … and it’s a peculiar wood, too, birch or alder.” He stepped back, sinking his hands into his pockets, his head tilted to one side. “On reflection…”

Jonathan groaned at the pun.

Tony grinned. “Sorry about that. It would seem a shame to remove the glass from the frame, unless we could put together a more ornate—but finding a frame of this size would be virtually impossible, it would have to be custom made. Let’s leave it as is.”

“The price, Tony,” Jonathan gently reminded him.

“I’d say about twenty thousand dollars … give or take a few.”

“What!”

Farren grinned at Jonathan’s surprise. “Why, what were you going to charge for it?”

“About seven grand, seventy-eight hundred maybe…”

“For twenty-eight square feet of what is possibly Venetian glass with what looks like an Elizabethan frame on it! That’d be like giving it away.”

“Could be a fake,” Jonathan suggested.

Tony Farren snorted rudely. He tapped the glass with his knuckles. “And this, by the way, is not going to go down in price. If we store it for a couple of years, it will double in value.”

Jonathan Frazer moved away from the huge mirror, looking at it in a new light. He sank down onto a badly made copy of a Chippendale and began to laugh gently. “I paid five hundred English pounds for it. So with the exchange rate and freight, approximately thirty-five hundred dollars.”

Tony shook his head. “It’s a once in a lifetime bargain.”

“A piece of good fortune, indeed!”

Farren smiled. “Every dealer—whether he’s dealing in books, stamps, coins, furniture, pictures or silver—turns up one special item in their lifetime.” He rested his hand against the glass, a damp palm print forming on the surface only to disappear almost immediately. “This could very well be your special item.”

Frazer checked his watch. He looked at the mirror one final time. Maybe he wouldn’t sell it. Not yet anyway. With the economy tanking, this might be worth hanging onto. “I’ll be at the store if you need me.” He looked at Tony. “Take special care of it for me.”

“I will. I’ll start refurbishing it immediately. I’m quite looking forward to it,” he added, rubbing his right hand across the mirror again. “Just think: if this glass could talk. What has it seen?” he wondered aloud.

“You say that about every single item I bring in here.”

“Everything has a story,” Tony said to Jonathan’s retreating back. “You know what I’ve always told you…”

“I know, I know. I’m not selling antiques—I’m selling stories.”

* * *

TONY FARREN WAS born in the Sunset District of San Francisco. His parents, post-war sweethearts, settled there after World War II. At the age of eighteen, uneducated Farren was drafted to Vietnam. He served one year before returning to the US with no skills other than how to handle and fire—with extraordinary accuracy—an M60 machine gun. Farren had moved to Los Angeles in the hope of finding a new life for himself. He drifted from trade to trade—painting, glazing, building, carpentry, plumbing and electrical—learning enough to be competent in each, but eventually finding each job remarkably boring.

James Frazer was in the process of opening an antiques store in Hollywood and he needed a handyman, someone who could fix the leg of a chair, refinish a tabletop, touch up a painting.

During his interview Tony Farren lied; he told James Frazer he could do all these things and more. And there was no one more surprised than he was, when he actually discovered that he could. He improved his basic skills by studying, and his solutions to the problems presented to him on a daily basis, whilst unorthodox, usually worked. James Frazer claimed he was a genius; Tony put it down to the fact that he was finally doing something he enjoyed. Every day was different: one day he might be working on chairs or tables, the next re-wiring a crystal chandelier or mending the hinge on an antique armoire, and the day after faux finishing a night stand.

Tony Farren had spent over forty-five years in the business working alongside James Frazer, growing the company, eventually becoming one of its master craftsmen as well as a recognized authority on the history of eighteenth century antique furniture. Over the years, he had seen just about every type of antique and artifact … but he had never seen anything quite like it.

He walked slowly around the mirror—certainly the largest he had ever seen. It was a sheet of glass set into a plain wooden frame, with a solid wooden back fixed to the frame. Obviously the back would have to be removed before he started work.

Tony fished into his back pocket and removed a magnifying glass, then bent to examine one of the clips which secured the back to the frame. He hissed in annoyance: the heads of two of the screws were entirely destroyed, the grooves worn smooth. He moved onto the next screw and frowned; this too had been destroyed. Moving slowly from clip to clip—there were twelve in all, two screws to a clip—he discovered that the heads of all twenty-four screws had been worn completely smooth, the grooves hacked and torn away. He rubbed a callused palm against the wooden backing. It looked deliberate.

“Whoever put you on didn’t want you coming off.”

However, the problem wasn’t insurmountable. The trick was to cut new heads in the screws, make a groove deep enough to give him purchase for a screwdriver. There was always the danger that the screw would snap—and that would be a bitch, but he’d cross that bridge when he came to it.

Farren moved over to the long workbench. It was a chaos of tools and littered with half-completed projects. The workbench had been the despair of numerous assistants down through the years. While they searched frantically for tools, he had always been able to go exactly to the place he had last left it. He chose a small Black & Decker and fitted a circular abrading stone to it. Then he slipped a pair of tinted protective glasses over his own and pulled on a pair of gloves. And then, with infinite patience, he carefully cleaned the ragged metal off the heads of the crude screws. It took him the best part of an hour, starting with those he could easily reach and then climbing up onto a stepladder to complete the job. When he was finished, the heads gleamed silver, sparkling in the light.

Returning to the bench, he replaced the Black & Decker with a diamond-tipped drill. He took a few moments to review what he was about to do and then, satisfied, knelt on the floor beside the mirror. This was the tricky bit.

“Don’t try this at home kids,” he murmured, as he maneuvered the drill in a reasonably straight line down the center of the first screw. Sparks flew and the soft, musty air was tainted with the sharp tang of scorched metal. It took him about three tense minutes to cut the groove, but when he fitted the screwdriver head into the groove, it slotted neatly into place. He grunted in quiet satisfaction.

No problem.

Tony Farren had cut twenty-two of the twenty-four screws when the accident happened. He was tired; he’d been working for over an hour just cutting the grooves and his neck and shoulder muscles were bunched and his eyes felt gritty, nerves twitching in his eyelids. “God, I’m getting too old for this,” he muttered under his breath. He should have stopped for lunch over an hour ago, but far better to get this bit finished, grab a bite to eat and then proceed. He moved the ladder along to the last clip and climbed up with the drill clutched in his right hand. He had just about reached the top when the stepladder shifted. Farren yelped with fright and dropped the drill, scrabbling to catch the expensive piece of equipment, missing it, hearing it crack onto the concrete floor. He toppled forward, instinctively clutching at the top of the mirror for support. He immediately realized what he was doing and attempted to push himself back, terrified that he was going to push the mirror to the ground. The stepladder swayed with the violence of his movements, metal legs screeching on the floor. Tony Farren crashed to the ground, his head cracking against the solid floor, right hip popping with the sickening force, shards of metal from the shattered drill casing digging into his flesh. Luckily the heavy metal stepladder had pushed away from him as he fell and went clattering across the floor.