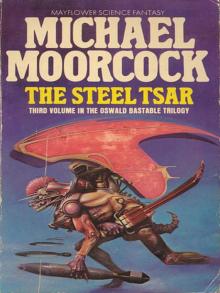

The Steel Tsar

Michael Moorcock

The Steel Tsar

Oswald Bastable Trilogy

Book III

Michael Moorcock

Content

Introduction

Part One

1. The Manner of My Dying

2. The Destruction of Singapore

3. The Crash

4. Prisoners

5. The Price of Fishing Boats

6. The Mysterious Dempsey

7. Dead Man

8. The Message

9. Hopes of Salvation

10. Lost Hopes

Part Two

1. The Camp on Rishiri

2. Back in Service

3. Cossack Revolutionists

4. The Black Ships

5. A Question of Attitudes

6. Secret Weapons

7. A Mechanical Man

8. A Kind of Revolution

Editor's Afterword

Introduction

The discovery and subsequent publication of two manuscripts left in the possession of my grandfather has led to a considerable amount of speculation as to their authenticity and authorship. The manuscripts consisted of one made in my grandfather's hand and taken down from the mysterious

Captain Bastable whom he met on Rowe Island in the early years of this century, and another, apparently written by Bastable himself, which was left with my grandfather when he visited China searching for the man who had become, he was told, 'a nomad of the time-streams'.

These very slightly edited texts were published by me as THE WARLORD OF THE AIR and THE LAND LEVIATHAN and I was certain that it was the last I should ever know of Bastable's adventures. When I remarked in a concluding note to THE LAND LEVIATHAN that I hoped Una Persson would some day pay me a visit I was being ironic. I did not believe that I should ever meet the famous chrononaut. As luck would have it, I began to receive visits from her very shortly after I had prepared THE LAND LEVIATHAN. She seemed glad to have me to talk to and gave me permission to use much of what she told me about her experiences in our own and others' time-streams. On the matter of Oswald Bastable, however, she was incommunicative and I learned very quickly not to pump her. Most of my references to him in other books (for instance THE DANCERS AT THE END OF TIME) were highly speculative.

In the late spring of 1979, shortly after I had finished a novel and was resting from the consequent exhaustion, which had left my private life in ruins and my judgment considerably weakened, I had a visit from Mrs. Persson at my flat in London. I was in no mood to see another human being, but she had heard from somewhere (or perhaps had already seen from the future) that I was in distress and had come to ask if there was anything she could do for me. I said that there was nothing. Time and rest would deal with my problems.

She acknowledged this and, with a small smile, added: 'But eventually you will need to work.'

I suppose I said something self-pitying about never being able to work again (I share that in common with almost every creative person I know) and she did not attempt to dissuade me from the notion.

'However,' she said, 'if you do ever happen to feel the urge, I'll be in touch.'

Curiosity caught me. 'What are you talking about?'

'I have a story for you,' she said.

'I have plenty of stories,' I told her, 'but no will to do anything with them. Is it about Jherek Carnelian or the Duke of Queens?'

She shook her head. 'Not this time.'

'Everything seems pointless,' I said.

She patted me on the arm. 'You should go away for a bit. Travel.'

'Perhaps.'

'And when you come back to London, I'll have the story waiting,' she promised.

I was touched by her kindness and her wish to be of use and I thanked her. As it happened a friend fell ill in Los Angeles and I decided to visit him. I stayed far longer in the United States than I had originally planned and eventually, after a short stay in Paris, settled in England for a while in the spring of 1980.

As Una Persson had predicted, I was, of course, ready to work. And, as she had promised, she turned up one evening, dressed in her usual slightly old-fashioned clothes of a military cut. We enjoyed a drink and some general talk and I heard gossip from the End of Time, a period that has always fascinated me. Mrs. Persson is a seasoned time-traveler and usually knows what and what not to tell, for incautious words can have an enormous effect either on the time-streams themselves or on that rarity, like herself, the chrononaut who can travel through them more or less at will.

She has always told me that so long as people regard my stories as fiction and as long as they are fashioned to be read as fiction then neither of us should be victims of the Morphail Effect, which is Time's sometimes-radical method of readjusting itself. The Morphail Effect is manifested most evidently in the fact that, for most time-travelers, only 'forward' movement through time (i.e. into their own future) is possible. 'Backward' movement (a return to their present or past) or movement between the various alternative planes is impossible for anyone save those few who make up the famous Guild of Temporal Adventurers. I knew that Bastable had become a member of this Guild, but did not know how he had been recruited, unless it had been in the Valley of the Dawn by Mrs. Persson herself.

'I have brought you something,' she said. She settled herself in her armchair and reached down for a black document case. 'They are not complete, but they are the best I can do. The rest you will have to fill in from what I tell you and from your own perfectly good imagination.' It was a bundle of manuscript. I recognized the hand at once. It was Bastable's.

'Good God!' I was astonished. 'He's turning into a novelist!'

'Not exactly. These are fresh memoirs that are all. He's read the others and is perfectly satisfied with what you've done with them. He was extremely fond of your grandfather and says that he would be quite glad to continue the tradition with you. Particularly, he says, since you've had rather better success in getting his stories published!' She laughed.

The manuscript was a sizable one. I weighed it in my hand. 'So he was never able to find his own period again? Or return to the life he so desperately wanted?'

'That's not for me to say. You'll notice from the manuscript that there's little explanation as to how he came to the particular alternative time-stream he describes. Suffice to say he returned to Teku Benga, crossed into yet another continuum and found his way to the airship-yards at Benares. This time he was reconciled to what had happened and, being an experienced airshipman, claimed slight

Amnesia and a loss of papers. Eventually he got himself a mate's certificate, though it was impossible for him, without impeccable credentials, to find a berth with any of the major lines.'

I smiled. 'And he's still haunted by angst, I suppose?'

'To a degree, He has many lives on his conscience. He knows only worlds at war. But we of the Guild understand what a responsibility we carry and I think membership has helped him.'

'And I'll never meet him?'

'It's unlikely. This stream would probably reject him, turn him into that poor creature your grandfather described, flung this way and that through Time, with no control whatsoever over his destiny.'

'He has that in common with most of us,' I remarked.

She was amused. 'I see you're still not completely over your self-pity, Moorcock.'

I smiled and apologized. 'I'm very excited by this.' I held up the manuscript. 'Bastable presumably wants it published as soon as possible. Why?'

'Perhaps it's mere vanity. You know how people become once they see their names in print.'

'Poor?'

We both laughed at this.

'He trusts you, too,' she continued. 'He knows that you did not tamper with his work and also that he has been of some use to you in you

r researches.'

'As have you, Mrs. Persson.'

'I'm glad. We enjoy what you do.'

'You find my speculations funny?' I said.

'That, too. We leave it to your rather strange imagination to produce the necessary obfuscations!'

I looked at the manuscript. I was surprised to notice a few peculiar correspondences and coincidences when compared with my grandfather's first manuscript. Yet Bastable appeared not to make some of the connections the reader might make. I remarked on it to Mrs. Persson.

'Our minds can hold only so much,' she said. 'As I've mentioned before, sometimes we do suffer from genuine amnesia, or at least a kind of blocking out of much of our memory. It is one of the ways in which we are sometimes able to enter time-streams not open to the general run of chrononauts.'

'Time makes you forget?' I said ironically.

'Exactly.'

'As someone who affects anarchism,' I said. 'I'm curious about the references here to Kerensky's Russia. Could it be that—?'

She stopped me. 'I can't tell you any more until you have read the manuscript.'

'A world in which the Bolshevik Revolution did not take place. He hints at it in the other story . . .' I had often wondered what the Russian Empire would have been like in such circumstances, for one of my other abiding interests is in the Soviet Union and its literature, which was so badly stifled under Stalin.

'You must read what Bastable has written, then ask me some questions. I'll answer where I can. It is up to you, he says, how much "shape" you give it, as a professional writer. But he trusts you to preserve the basic spirit of the memoir.'

'I shall do my best.'

And here, for better or worse, is Oswald Bastable's third memoir. I have done as little work on it as possible and present it to the reader pretty much as I received it. As to its authenticity, that is for you to judge.

Michael Moorcock,

Three Chimneys,

Yorkshire, England.

June 1980

Part One

An English Airshipman's Adventures

In The Great War Of 1941

1.

The Manner of My Dying

It was, I think, my fifth day at sea when the revelation came. Just as at some stage of his existence a man can reach a particular decision about how to lead his life, so can he come to a similar decision about how to encounter death. He can face the grim simple truth of his dying, or he can prefer to lose himself in some pleasant fantasy, some dream of heaven or of salvation, and so face his end almost with pleasure.

On my sixth day at sea it was obvious that I was to die and it was then that I chose to accept the illusion rather than the reality.

I had lain all morning at the bottom of the dugout. My face was pressed against wet, steaming wood. The tropical sun throbbed down on the back of my unprotected head and blistered my withered flesh. The slow drumming of my heart filled my ears and counter pointed the occasional slap of a wave against the side of the boat.

All I could think was that I had been spared one kind of death in order to die alone out here on the ocean. And I was grateful for that. It was much better than the death I had left behind.

Then I heard the cry of the seabird and I smiled a little to myself. I knew that the illusion was beginning. There was no possibility that I was in sight of land and therefore I could not really have heard a bird. I had had many similar auditory hallucinations in recent days.

I began to sink into what I knew must be my final coma. But the cry grew more insistent. I rolled over and blinked in the white glare of the sun. I felt the boat rock crazily with the movement of my thin body. Painfully I raised my head and peered through a shifting haze of silver and blue and saw my latest vision. It was a very fine one: more prosaic than some, but more detailed, too.

I had conjured up an island. An island rising at least a thousand feet out of the water and about ten miles long and four miles wide: a monstrous pile of volcanic basalt, limestone and coral, with deep green patches of foliage on its flanks.

I sank back into the dugout, squeezing my eyes shut and congratulating myself on the power of my own imagination. The hallucinations improved as any hopes of surviving vanished. I knew it was time to give myself up to madness, to pretend that the island was real and so die a pathetic rather than a dignified death.

I chuckled. The sound was a dry, death rattle.

Again the seabird screamed.

Why rot slowly and painfully for perhaps another thirty hours when I could die now in a comforting dream of having been saved at the last moment?

With the remains of my strength I crawled to the stern and grasped the starting cord of the outboard. Weakly I jerked at it. Nothing happened. Doggedly, I tried again. And again. And all the while I kept my eyes on the island, waiting to see if it would shimmer and disappear before I could make use of it.

I had seen so many visions in the past few days. I had seen milk-white angels with crystal cups of pure water drifting just out of my reach. I had seen blood-red devils with fiery pitchforks piercing my skin.

I had seen enemy airships, which popped like bubbles just as they were about to release their bombs on me. I had seen orange-sailed schooners as tall as the Empire State Building. I had seen schools of tiny black whales. I had seen rose-colored coral atolls on which lounged beautiful young women whose faces turned into the faces of Japanese soldiers as I came closer and who then slid beneath the waves where I was sure they were trying to capsize my boat. But this mirage retained its clarity no matter how hard I stared and it was so much more detailed than the others.

The engine fired after the tenth attempt to start it. There was hardly any fuel left. The screw squealed, rasped and began to turn. The water foamed. The boat moved reluctantly across a flat sea of burnished steel, beneath a swollen and throbbing disc of fire, which was the sun, my enemy.

I straightened up, squatting like a desiccated old toad on the floor of the boat, whimpering as I gripped the tiller, for its touch sent shards of fire through my hand and into my body.

Still the hallucination did not waver; it even appeared to grow larger as I approached it. I completely forgot my pain as I allowed myself to be deceived by this splendid mirage.

I steered under brooding gray cliffs, which fell sheer into the sea. I came to the lower slopes of the island and saw palms, their trunks bowed as if in prayer, swaying over sharp rocks washed by white surf. There was even a brown crab scuttling across a rock; there was weed and lichen of several varieties; seabirds diving in the shallows and darting upwards with shining fish in their long beaks. Perhaps the island was real, after all . . .?

But then I had rounded a coral outcrop and at once discovered the final confirmation of my complete madness. For here was a high concrete wall: a harbor wall encrusted above the water line with barnacles and coral and tiny plants. It had been built to follow the natural curve of a small bay. And over the top of the wall I saw the roofs and upper stories of houses, which might have belonged to a town on any part of the English coast. And as a superb last touch there was a flagpole at which flew a torn and weather-stained Union Jack! My fantasy was complete. I had created an English fishing port in the middle of the Indian Ocean.

I smiled again. The movement caused the blistered skin of my lips to crack still more. I ignored the discomfort. Now all I had to do was enter the harbor, step off onto what I believed to be dry land - and drown. It was a fine way to die. I gave another hoarse, mad chuckle, full of self-admiration, and I abandoned myself to the world of my mind.

Guiding my boat round the wall I found the harbor mouth. It was partly blocked by the wreck of a steamer. Rust-red funnels and masts rose above the surface. The water was unclouded and as I passed I could see the rest of the sunken ship leaning on the pink coral with multicolored fish swimming in and out of its hatches and portholes. The name was still visible on her side: Jeddah, Manila.

Now I saw the little town quite clearly.

&nbs

p; The buildings were in that rather spare Victorian or Edwardian neoclassical style and had a distinctly run-down look about them. They seemed deserted and some were obviously boarded up. Could I not perhaps create a few inhabitants before I died? Even a laskar or two would be better than nothing, for I now realized that I had built a typical Outpost of Empire. These were colonial buildings, not English ones, and there were square, largely undecorated native buildings mixed in with them.

On the quay stood various sheds and offices. The largest of these bore the faded slogan Welland Rock Phosphate Company. A nice touch of mine. Behind the town stood something resembling a small and pitted version of the Eiffel Tower. A battered airship mooring mast! Even better!

Out from the middle of the quay stretched a stone mole. It had been built for engine-driven cargo ships, but there were only a few rather seedy looking native fishing dhows moored there now. They looked hardly seaworthy. I headed towards the mole, croaking out the words of the song I had not sung for the past two days.

'Rule Britannia, Britannia rules the waves! Britons never, never shall be - marr-I-ed to a mer-MI-ad at the bottom of the deep, blue sea!'

As if invoked by my chant Malays and Chinese materialized on the quayside. Some of them began to run along the jetty, their brown and yellow bodies gleaming in the sunshine, their thin arms gesticulating. They wore loincloths or sarongs of various colors and wide coolie hats of woven palm-leaves shaded their faces. I even heard their voices babbling in excitement as they approached.

I laughed as the boat bumped against the weed-grown jetty. I tried to stand up to address these wonderful creatures of my imagination. I felt godlike, I suppose. And to talk to them was the least, after all, that I could do. I opened my mouth. I spread my arms.

'My friends—'

And my starved body collapsed under me. I fell backwards into the dugout, striking my shoulder on the empty petrol can, which had contained my water.

There came a few words shouted in Pidgin English and a brown figure in patched white shorts jumped into the canoe, which rocked violently, jolting the last tatters of sense from my skull.