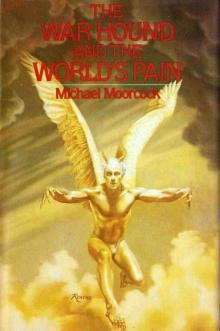

The War Hound and the World's Pain

Michael Moorcock

The War Hound and the World’s Pain

By Michael Moorcock

This novel is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places and incidents are either the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual events or locales or persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental.

Copyright © 1981 by Michael Moorcock

All rights reserved including the right of reproduction in whole or in part in any form

A Timescape Book

Published by Pocket Books,

A Simon & Schuster Division of Gulf & Western Corporation

Simon & Schuster Building

Rockefeller Center

1230 Avenue of the Americas

New York, New York 10020

Use of TIMESCAPE trademark under exclusive license of trademark owner

Manufactured in the United States of America

Being the true testimony of the Graf Ulrich von Bek, lately Commander of Infantry, written down in the Year of Our Lord 1680 by Brother Olivier of the Monastery at Renschel during the months of May and June as the said nobleman lay upon his sickbed.

(This manuscript had, until now, remained sealed within the wall of the monastery’s crypt. It came to light during work being carried out to restore the structure, which had sustained considerable damage during the Second World War. It came into the hands of the present editor via family sources and appears here for the first time in a modern translation. Almost all the initial translating work was that of Prinz Lobkowitz; this English text is largely the work of Michael Moorcock.)

Chapter I

IT WAS IN that year when the fashion in cruelty demanded not only the crucifixion of peasant children, but a similar fate for their pets, that I first met Lucifer and was transported into Hell; for the Prince of Darkness wished to strike a bargain with me.

Until May of 1631 I had commanded a troop of irregular infantry, mainly Poles, Swedes and Scots. We had taken part in the destruction and looting of the city of Magdeburg, having somehow found ourselves in the army of the Catholic forces under Count Johann Tzerclaes Tilly. Wind-borne gunpowder had turned the city into one huge keg and she had gone up all of a piece, driving us out with little booty to show for our hard work.

Disappointed and belligerent, wearied by the business of rapine and slaughter, quarrelling over what pathetic bits of goods they had managed to pull from the blazing houses, my men elected to split away from Tilly’s forces. His had been a singularly ill-fed and badly equipped army, victim to the pride of bickering allies. It was a relief to leave it behind us.

We struck south into the foothills of the Hartz Mountains, intending to rest. However, it soon became evident to me that some of my men had contracted the Plague, and I deemed it wise, therefore, to saddle my horse quietly one night and, taking what food there was, continue my journey alone.

Having deserted my men, I was not free from the presence of death or desolation. The world was in agony and shrieked its pain.

By noon I had passed seven gallows on which men and women had been hanged and four wheels on which three men and one boy had been broken. I passed the remains of a stake at which some poor wretch (witch or heretic) had been burned: whitened bone peering through charred wood and flesh.

No field was untouched by fire; the very forests stank of decay. Soot lay deep upon the road, borne by the black smoke which spread and spread from innumerable burning bodies, from sacked villages, from castles ruined by cannonade and siege; and at night my passage was often lit by fires from burning monasteries and abbeys. Day was black and grey, whether the sun shone or no; night was red as blood and white from a moon pale as a cadaver. All was dead or dying; all was despair.

Life was leaving Germany and perhaps the whole world; I saw nothing but corpses. Once I observed a ragged creature stirring on the road ahead of me, fluttering and flopping like a wounded crow, but the old woman had expired before I reached her.

Even the ravens of the battlegrounds had fallen dead upon the remains of their carrion, bits of rotting flesh still in their beaks, their bodies stiff, their eyes dull as they stared into the meaningless void, neither Heaven, Hell nor yet Limbo (where there is, after all, still a little hope).

I began to believe that my horse and myself were the only creatures allowed, by some whim of Our Lord, to remain as witnesses to the doom of His Creation.

If it were God’s intention to destroy His world, as it seemed, then I had lent myself most willingly to His purpose.

I had trained myself to kill with ease, with skill, with a cunning efficiency and lack of ambiguity. My treacheries were always swift and decisive. I had learned the art of passionless torture in pursuit of wealth and information. I knew how to terrify in order to gain my ends, whether they be the needs of the flesh or in the cause of strategy.

I knew how to soothe a victim as gently as any butcher soothes a lamb. I had become a splendid thief of grain and cattle so that my soldiers should be fed and remain as loyal as possible to me.

I was the epitome of a good mercenary captain; a soldier-of-fortune envied and emulated; a survivor of every form of danger, be it battle, Plague or pox, for I had long since accepted things as they were and had ceased either to question or to complain.

I was Captain Ulrich von Bek and I was thought to be lucky.

The steel I wore, helmet, breastplate, greaves and gloves, was of the very best, as was the sweat-soaked silk of my shirt, the leather of my boots and breeches. My weapons had been selected from the richest of those I had killed and were all, pistols, sword, daggers and musket, by the finest smiths. My horse was large and hardy and excellently furnished.

I had no wounds upon my face, no marks of disease, and, if my bearing was a little stiff, it gave me, I was told, an air of dignified authority, even when I conducted the most hideous destruction.

Men found me a good commander and were glad to serve with me. I had grown to some fame and had a nickname, occasionally used: Krieghund.

They said I had been born for War. I found such opinions amusing.

My birthplace was in Bek. I was the son of a pious nobleman who was loved for his good works. My father had protected and cared for his tenants and his estates. He had respected God and his betters. He had been learned, after the standards of this time, if not after the standards of the Greeks and Romans, and had come to the Lutheran religion through inner debate, through intellectual investigation, through discourse with others. Even amongst Catholics he was known for his kindness and had once been seen to save a Jew from stoning in the town square. He had a tolerance for almost every creature.

When my mother died, quite young, having given birth to the last of my sisters (I was the only son), he prayed for her soul and waited patiently until he should join her in Heaven. In the meantime he followed God’s Purpose, as he saw it, and looked after the poor and weak, discouraged them in certain aspirations which could only lead the ignorant souls into the ways of the Devil, and made certain that I acquired the best possible education from both clergymen and lay tutors.

I learned music and dancing, fencing and riding, as well as Latin and Greek. I was knowledgeable in the Scriptures and their commentaries. I was considered handsome, manly, God-fearing, and was loved by all in Bek.

Until 1625 I had been an earnest scholar and a devout Protestant, taking little interest (save to pray for our cause) in the various wars and battles of the North.

Gradually, however, as the canvas grew larger and the issues seemed to become more crucial, I determined to obey God and my conscience as best I could.

In the pursuit of my Faith, I had raised a company of infantry and gone off to serv

e in the army of King Christian of Denmark, who proposed, in turn, to aid the Protestant Bohemians.

Since King Christian’s defeat, I had served a variety of masters and causes, not all of them, by any means, Protestant and a good many of them in no wise Christian by even the broadest description. I had also seen a deal of France, Sweden, Bohemia, Austria, Poland, Muscovy, Moravia, the Low Countries, Spain and, of course, most of the German provinces.

I had learned a deep distrust of idealism, had developed a contempt for any kind of unthinking Faith, and had discovered a number of strong arguments for the inherent malice, deviousness and hypocrisy of my fellow men, whether they be Popes, princes, prophets or peasants.

I had been brought up to the belief that a word given meant an appropriate action taken. I had swiftly lost my innocence, for I am not a stupid man at all.

By 1626 I had learned to lie as fluently and as easily as any of the major participants of that War, who compounded deceit upon deceit in order to achieve ends which had begun to seem meaningless even to them; for those who compromise others also compromise themselves and are thus robbed of the capacity to place value on anything or anyone. For my own part I placed value upon my own life and trusted only myself to maintain it.

Magdeburg, if nothing else, would have proven those views of mine:

By the time we had left the city we had destroyed most of its thirty thousand inhabitants. The five thousand survivors had nearly all been women and their fate was the obvious one.

Tilly, indecisive, appalled by what he had in his desperation engineered, allowed Catholic priests to make some attempt to marry the women to the men who had taken them, but the priests were jeered at for their pains.

The food we had hoped to gain had been burned in the city. All that had been rescued had been wine, so our men poured the contents of the barrels into their empty bellies.

The work which they had begun sober, they completed drunk. Magdeburg became a tormented ghost to haunt those few, unlike myself, who still possessed a conscience.

A rumor amongst our troops was that the fanatical Protestant, Falkenburg, had deliberately fired the city rather than have it captured by Catholics, but it made no odds to those who died or suffered. In years to come Catholic troops who begged for quarter from Protestants would be offered “Magdeburg mercy” and would be killed on the spot. Those who believed Falkenburg the instigator of the fire often celebrated him, calling Magdeburg “the Protestant Lucretia,” self-murdered to protect her honour. All this was madness to me and best forgotten.

Soon Magdeburg and my men were days behind me. The smell of smoke and the Plague remained in my nostrils, however, until well after I had turned out of the mountains and entered the oak groves of the northern fringes of the great Thuringian Forest.

Here, there was a certain peace. It was spring and the leaves were green and their scent gradually drove the stench of slaughter away.

The images of death and confusion remained in my mind, nonetheless. The tranquility of the forest seemed to me artificial. I suspected traps.

I could not relax for thinking that the trees hid robbers or that the very ground could disguise a secret pit. Few birds sang here; I saw no animals.

The atmosphere suggested that God’s Doom had been visited on this place as freely as it had been visited elsewhere. Yet I was grateful for any kind of calm, and after two days without danger presenting itself I found that I could steep quite easily for several hours and could eat with a degree of leisure, drinking from sweet brook water made strange to me because it did not taste of the corpses which clogged, for instance, the Elbe from bank to bank.

It was remarkable to me that the deeper into the forest I moved, the less life I discovered.

The stillness began to oppress me; I became grateful for the sound of my own movements, the tread of the horse’s hooves on the turf, the occasional breeze which swept the leaves of the trees, animating them and making them seem less like frozen giants observing my passage with a passionless sense of the danger lying ahead of me.

It was warm and I had an impulse more than once to remove my helmet and breastplate, but I kept them firmly on, sleeping in my armour as was my habit, a naked sword ready by my hand.

I came to believe that this was not, after all, a Paradise, but the borderland between Earth and Hell.

I was never a superstitious man, and shared the rational view of the universe with our modern alchemists, anatomists, physicians and astrologers; I did not explain my fears in terms of ghosts, demons, Jews or witches; but I could discover no explanation for this absence of life.

No army was nearby, to drive game before it. No large beasts stalked here. There were not even huntsmen. I had discovered not a single sign of human habitation.

The forest seemed unspoiled and untouched since the beginning of Time. Nothing was poisoned, I had eaten berries and drunk water. The undergrowth was lush and healthy, as were the trees and shrubs. I had eaten mushrooms and truffles; my horse nourished on the good grass.

Through the treetops I saw clear blue sky, and sunlight warmed the glades. But no insects danced in the beams; no bees crawled upon the leaves of the wild flowers; not even an earthworm twisted about the roots, though the soil was dark and smelled fertile.

It came to me that perhaps this was a part of the globe as yet unpopulated by God, some forgotten corner which had been overlooked during the latter days of the Creation. Was I a wandering Adam come to find his Eve and start the race again? Had God, feeling hopeless at humanity’s incapacity to maintain even a clear idea of His Purpose, decided to expunge His first attempts? But I could only conclude that some natural catastrophe had driven the animal kingdom away, be it through famine or disease, and that it had not yet returned.

You can imagine that this state of reason became more difficult to maintain when, breaking out of the forest proper one afternoon, I saw before me a green, flowery hill which was crowned by the most beautiful castle I had ever beheld: a thing of delicate stonework, of spires and ornamental battlements, all soft, pale browns, whites and yellows, and this castle seemed to me to be at the centre of the silence, casting its influence for miles around, protecting itself as a nun might protect herself, with cold purity and insouciant confidence. Yet it was mad to think such a thing, I knew.

How could a building demand calm, to the degree that not even a mosquito would dare disturb it?

It was my first impulse to avoid the castle, but my pride overcame me.

I refused to believe that there was anything genuinely mysterious.

A broad, stony path wound up the hillside between banks of flowers and sweet-smelling bushes which gradually became shaped into terraced gardens with balustrades, statuary and formally arranged flower beds.

This was a peaceful place, built for civilized tastes and reflecting nothing of the War. From time to time as I rode slowly up the path I called out a greeting, asking for shelter and stating my name, according to accepted tradition; but there was no reply. Windows filled with stained glass glittered like the eyes of benign lizards, but I saw no human eye, heard no voice.

Eventually I reached the open gates of the castle’s outer wall and rode beneath a portcullis into a pleasant courtyard full of old trees, climbing plants and, at the centre, a well. Around this courtyard were the apartments and appointments of those who would normally reside here, but it was plain to me that not a soul occupied them.

I dismounted from my horse, drew a bucket from the well so that he might drink, tethered him lightly and walked up the steps to the main doors which I opened by means of a large iron handle.

Within, it was cool and sweet.

There was nothing sinister about the shadows as I climbed more steps and entered a room furnished with old chests and tapestries. Beyond this were the usual living quarters of a wealthy nobleman of taste. I made a complete round of the rooms on all three stories.

There was nothing in disorder. The books and manuscripts in the library wer

e in perfect condition. There were preserved meats, fruits and vegetables in the pantries, barrels of beer and jars of wine in the cellars.

It seemed that the castle had been left with a view to its inhabitants’ early return. There was no decay at all. But what was remarkable to me was that there were, as in the forest, no signs of the small animals, such as rats and mice, which might normally be discovered.

A little cautiously I sampled the castle’s larder and found it excellent. I would wait, however, for a while before I made a meal, to see how my stomach behaved.

I glanced through the windows, which on this side were glazed with clear, green glass, and saw that my horse was content. He had not been poisoned by the well water.

I climbed to the top of one of the towers and pushed open a little wooden door to let myself onto the battlements.

Here, too, flowers and vegetables and herbs grew in tubs and added to the sweetness of the air.

Below me, the treetops were like the soft waves of a green and frozen sea. Able to observe the land for many miles distant and see no sign of danger, I became relieved.

I went to stable my horse and then explored some of the chests to see if I could discover the name of the castle’s owner. Normally one would have come upon family histories, crests and the like. There were none.

The linen bore no mottoes or insignia, the clothing (of which quantities existed to dress most ages and both sexes) was of good quality, but anonymous. I returned to the kitchens, lit a fire and began to heat water so that I might bathe and avail myself of some of the softer apparel in the chests.

I had decided that this was probably the summer retreat of some rich Catholic prince who now did not wish to risk the journey from his capital, or who had no time for rest.

I congratulated myself on my good fortune. I toyed with the idea of audaciously making the castle my own, of finding servants for it, perhaps a woman or two to keep me company and share one of the large and comfortable beds I had already sampled. Yet how, short of robbery, would I maintain the place?