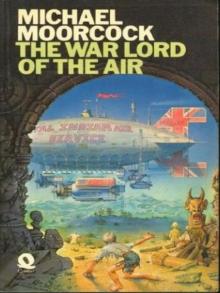

The Warlord of the Air

Michael Moorcock

The Warlord Of

The Air

Oswald Bastable Trilogy

Book I

Michael Moorcock

Content

Book One

Chapter I The Opium Eater of Rowe Island

Chapter II The Temple at Teku Benga

Chapter III The Shadow from the Sky

Chapter IV An Amateur Archaeologist

Chapter V My First Sight of Utopia

Chapter VI A Man Without a Purpose

Book Two

Chapter I A Question of Employment

Chapter II A Man with a Big Stick

Chapter III Disaster—and Disgrace!

Chapter IV A Bohemian ‘Brother’

Chapter V Captain Korzeniowski

Book Three

Chapter I General O. T. Shaw

Chapter II The Valley of the Morning

Chapter III Chi’ng Che’eng Ta-Chia

Chapter IV Vladimir Ilyitch Ulianov

Chapter V The Coming of the Air Fleets

Chapter VI Another Meeting with the Amateur Archaeologist

Chapter VII Project NFB

Chapter VIII The Lost Man

Editor’s Note

Book One

HOW AN ENGLISH ARMY OFFICER ENTERED THE WORLD OF THE FUTURE AND WHAT HE SAW THERE.

Chapter I

The Opium Eater of Rowe Island

IN THE SPRING of 1903, on the advice of my physician, I had occasion to visit that remote and beautiful fragment of land in the middle of the Indian Ocean which I shall call Rowe Island. I had been overworking and had contracted what the quacks now like to term ‘exhaustion’ or even ‘nervous debility’. In other words I was completely whacked out and needed a rest a long way away from anywhere. I had a small interest in the mining company which is the sole industry of the island (unless you count Religion!) and I knew that its climate was ideal, as was its location—one of the healthiest places in the world and fifteen hundred miles from any form of civilisation. So I purchased my ticket, packed my boxes, bade farewell to my nearest and dearest, and boarded the liner which would take me to Jakarta. From Jakarta, after a pleasant and uneventful voyage, I took one of the company boats to Rowe Island. I had managed the journey in less than a month.

Rowe Island has no business to be where it is. There is nothing near it. There is nothing to indicate that it is there. You come upon it suddenly, rising out of the water like the tip of some vast underwater mountain (which, in fact, it is). It is a great wedge of volcanic rock surrounded by a shimmering sea which resembles burnished metal when it is still or boiling silver and molten steel when it is testy. The rock is about twelve miles long by five miles across and is thickly wooded in places, bare and severe in other parts. Everything goes uphill until it reaches the top and then, on the other side of the hill, the rock simply falls away, down and down into the sea a thousand feet below.

Built around the harbour is a largish town which, as you approach it, resembles nothing so much as a prosperous Devon fishing village—until you see the Malay and Chinese buildings behind the facades of the hotels and offices which line the quayside. There is room in the harbour for several good sized steamers and a number of sailing vessels, principally native dhows and junks which are used for fishing. Further up the hill you can see the workings of the mines which employ the greatest part of the population which is Malay and Chinese labourers and their wives and families. Prominent on the quayside are the warehouses and offices of the Welland Rock Phosphate Mining Company and the great white and gold facade of the Royal Habour Hotel of which the proprietor is one Minheer Olmeijer, a Dutchman from Surabaya. There are also an almost ungodly number of missions, Buddhist temples, Malay mosques and shrines of more, mysterious origin. There are several less ornate hotels than Olmeijer’s, there are general stores, sheds and buildings which serve the tiny railway which brings the ore down from the mountain and along the quayside. There are three hospitals, two of which are for natives only. I say ‘natives’ in the loose sense. There were no natives of any sort before the island was settled thirty years ago by the people who founded the Welland firm; all labour was brought from the Peninsula, mainly from Singapore. On a hill to the south of the harbour, standing rather aloof from the town and dominating it, is the residence of the Official Representative, Brigadier Bland, together with the barracks which houses the small garrison of native police under the command of a very upright servant of the Empire, Lieutenant Allsop. Over this spick and span collection of whitewashed stucco flies a proud Union Jack, symbol of protection and justice to all who dwell on the island.

Unless you are fond of paying an endless succession of social calls on the other English people, most of whom can talk only of mining or of missions, there is not a great deal to do on Rowe Island. There is an amateur dramatic society which puts on a play at the Official Representative’s residence every Christmas, there is a club of sorts where one may play billiards if invited by the oldest members (I was invited once but played rather badly). The local newspapers from Singapore, Sarawak or Sydney are almost always at least a fortnight old, when you can find them, the Times is a month to six weeks old and the illustrated weeklies and monthly journals from home can be anything up to six months old by the time you see them. This sparsity of up-to-date news is, of course, a very good thing for a man recovering from exhaustion. It is hard to get hot under the collar about a war which has been over a month or two before you read about it or a stock market tremor which has resolved itself one way or the other by the previous week. You are forced to relax. After all, there is nothing you can do to alter the course of what has become history. But it is when you have begun to recover your energy, both mental and physical, that you begin to realise how bored you are—and within two months this realisation had struck me most forcibly. I began to nurse a rather evil hope that something would happen on Rowe Island—an explosion in the mine, an earthquake, or perhaps even a native uprising.

In this frame of mind I took to haunting the harbour, watching the ships loading and unloading, with long lines of coolies carrying sacks of corn and rice away from the quayside or guiding the trucks of phosphate up the gangplanks to dump them in the empty holds. I was surprised to see so many women doing work which in England few would have thought women could do! Some of these women were quite young and some were almost beautiful. The noise was almost deafening when a ship or several ships were in port. Naked brown and yellow bodies milled everywhere, like so much churning mud, sweating in the intense heat—a heat relieved only by the breezes off the sea.

It was on one such day that I found myself down by the harbour, having had my lunch at Olmeijer’s hotel, where I was staying, watching a steamer ease her way towards the quay, blowing her whistle at the junks and dhows which teemed around her. Like so many of the ships which ply that part of the world, she was sturdy but unlovely to look upon. Her hull and superstructure were battered and needed painting and her crew, mainly laskars, seemed as if they would have been more at home on some Malay pirate ship. I saw the captain, an elderly Scot, cursing at them from his bridge and bellowing incoherently through a megaphone while a half-caste mate seemed to be performing some peculiar, private dance of his own amongst the seamen. The ship was the Maria Carlson bringing provisions and, I hoped, some mail. She berthed at last and I began to push my way through the coolies towards her, hoping she had brought me some letters and the journals which I had begged my brother to send me from London.

The mooring ropes were secured, the anchor dropped and the gangplanks lowered and then the half-caste mate, his cap on the back of his head, his jacket open, came springing down, howling at the coolies who gathered there waving the scraps of paper they had receiv

ed at the hiring office. As he howled he gathered up the papers and waved wildly at the ship, presumably issuing instructions. I hailed him with my cane.

“Any mail?” I called.

“Mail? Mail?” He offered me a look of hatred and contempt which I took for a negative reply to my question. Then he rushed back up the gangplank and disappeared. I waited, however, in the hope of seeing the captain and confirming with him that there was, indeed, no mail. Then I saw a white man appear at the top of the gangplank, pausing and staring blankly around him as if he had not expected to find land on the other side of the rail at all. Someone gave him a shove from behind and he staggered down the bouncing plank, fell at the bottom and picked himself up in time to catch the small seabag which the mate threw to him from the ship.

The man was dressed in a filthy linen suit, had no hat, no shirt. He was unshaven and there were native sandles on his feet. I had seen his type before. Some wretch whom the East had ruined, who had discovered a weakness within himself which he might never have found if he had stayed safely at home in England. As he straightened up, however, I was startled by an expression of intense misery in his eyes, a certain dignity of bearing which was not at all common in the type. He shouldered his bag and began to make his way towards the town.

“And don’t try to get back aboard, mister, or the law will have you next time!” screamed the mate of the Maria Carlson after him. The down-and-out hardly seemed to hear. He continued to plod along the quayside, jostled by the coolies, frantic for work.

The mate saw me and gesticulated impatiently. “No mail. No mail.”

I decided to believe him, but called: “Who is that chap? What’s he done?”

“Stowaway,” was the curt reply.

I wondered why anyone should want to stow away on a ship bound for Rowe Island and on impulse I turned and followed the man. For some reason I believed him to be no ordinary derelict and he had piqued my curiosity. Besides, my boredom was so great that I should have welcomed any relief from it. Also I was sure that there was something different about his eyes and his bearing and that, if I could encourage him to confide in me, he would have an interesting story to tell Perhaps I felt sorry for him, too. Whatever the reason, I hastened to catch him up and address him.

“Don’t be offended,” I said, “but you look to me as if you could make some use of a square meal and maybe a drink.”

“Drink?”

He turned those strange, tormented eyes on me as if he had recognised me as the Devil himself. “Drink?”

“You look all up, old chap.” I could hardly bear to look into that face, so great was the agony I saw there. “You’d better come with me.”

Unresistingly, he let me lead him down the harbour road until we reached Olmeijer’s. The Indian servants in the lobby weren’t happy about my bringing in such an obvious derelict, but I led him straight upstairs to my suite and ordered my houseboy to start a bath at once. In the meantime I sat my guest down in my best chair and asked him what he would like to drink.

He shrugged. “Anything. Rum?”

I poured him a stiffish shot of rum and handed him the glass. He downed it in a couple of swallows and nodded his thanks. He sat placidly in the chair, his hands folded in his lap, staring at the table.

His accent, though distant and bemused, had been that of a cultivated man—a gentleman—and this aroused my curiosity even further.

“Where are you from?” I asked him. “Singapore?”

“From?” He gave me an odd look and then frowned to himself. He muttered something which I could not catch and then the houseboy entered and told me that he had prepared the bath.

“The bath’s ready,” I said. “If you’d like to use it I’ll be looking out one of my suits. We’re about the same size.”

He rose like an automaton and followed the house-boy into the bathroom, but then he re-emerged almost at once. “My bag,” he said.

I picked up the bag from the floor and handed it to him. He went back into the bathroom and closed the door.

The houseboy looked curiously at me. “Is he some-some relative, sahib?”

I laughed. “No, Ram Dass. He is just a man I found on the quay.”

Ram Dass smiled. “Aha! It is the Christian charity.” He seemed satisfied. As a recent convert (the pride of one of the local missions) he was constantly translating all the mysterious actions of the English into good, simple Christian terms. “He is a beggar, then? You are the Samaritan?”

“I’m not sure I’m as selfless as that,” I told him. “Will you fetch one of my suits for the gentleman to put on after he has had his bath?”

Ram Dass nodded enthusiastically. “And a shirt, and a tie, and socks, and shoes—everything?”

I was amused. “Very well. Everything.”

My guest took a very long time about his ablutions, but came out of the bathroom at last looking much more spruce than when he had gone in. Ram Dass had dressed him in my clothes and they fitted extraordinarily well, though a little loose, for I was considerably better fed than he. Ram Dass behind him brandished a razor as bright as his grin. “I have shaved the gentleman, sahib!”

The man before me was a good-looking young man in his late twenties, although there was something about the set of his features which occasionally made him look much older. He had golden wavy hair, a good jaw and a firm mouth. He had none of the usual signs of weakness which I had learned to recognise in the others of his kind I had seen. Some of the pain had gone out of his eyes, but had been replaced by an even more remote—even dreamy—expression. It was Ram Dass, sniffing significantly and holding up a long, carved pipe behind the man, who gave me the clue.

So that was it! My guest was an opium eater! He was addicted to a drug which some had called the Curse of the Orient, which contributed much to that familiar attitude of fatalism we equate with the East, which robbed men of their will to eat, to work, to indulge in any of the usual pleasures with which others beguile their hours—a drug which eventually kills them.

With an effort I managed to control any expression of horror or pity which I might feel and said instead:

“Well, old chap, what do you say to a late lunch?”

“If you wish it,” he said distantly.

“I should have thought you were hungry.”

“Hungry? No.”

“Well, at any rate, we’ll get something brought up. Ram Dass? Could you arrange for some food? Perhaps something cold. And tell Mnr. Olmeijer that I shall have a guest staying the night We’ll need sheets for the other bed and so on.”

Ram Dass went away and, uninvited, my guest crossed to the sideboard and helped himself to a large whisky. He hesitated for a moment before pouring in some soda. It was almost as if he were trying to remember how to prepare a drink.

“Where were you making for when you stowed away?” I asked. “Surely not Rowe Island?”

He turned, sipping his drink and staring through the window at the sea beyond the harbour. “This is Rowe Island?”

“Yes. The end of the world in many respects.”

“The what?” He looked at me suspiciously and I saw a hint of that torment in his eyes again.

“I was speaking figuratively. Not much to do on Rowe Island. Nowhere to go, really, except back where you came from. Where did you come from, by the way?”

He gestured vaguely. “I see. Yes. Oh, Japan, I suppose.”

“Japan? You were in the foreign service there, perhaps?”

He looked at me intently as if he thought my words had some hidden meaning. Then he said: “Before that, India. Yes, India before that. I was in the Army.”

“How—?” I was embarrassed. “How did you come to be aboard the Maria Carlson—the ship which brought you here?”

He shrugged. “I’m afraid I don’t remember. Since I left—since I came back—it has been like a dream. Only the damned opium helps me forget. Those dreams are less horrifying.”

“You take opium?” I felt like a

hypocrite, framing the question like that.

“As much as I can get hold of.”

“You seem to have been through some rather terrible experience,” I said, forgetting my manners completely.

He laughed then, more in self-mockery than at me. “Yes! Yes. It turned me mad. That’s what you’d think, anyway. What’s the date, by the way?”

He was becoming more communicative as he downed his third drink.

“It’s the 29th of May,” I told him.

“What year?”

“Why, 1903!”

“I knew that really. I knew it.” He spoke defensively now. “1903, of course. The beginning of a bright new century—perhaps even the last century of the world.”

From another man, I might have taken these disconnected ramblings to be merely the crazed utterances of the opium fiend, but from him they seemed oddly convincing. I decided it was time to introduce myself and did so.

He chose a peculiar way in which to respond to this introduction. He drew himself up and said: “This is Captain Oswald Bastable, late of the 53rd Lancers.” He smiled at this private joke and went and sat down in an armchair near the window.

A moment later, while I was still trying to recover myself, he turned his head and looked up at me in amusement. “I’m sorry, but you see I’m in a mood not to try to disguise my madness. You’re very kind.” He raised his glass in a salute. “I thank you. I must try to remember my manners. I had some once. They were a fine set of manners. Couldn’t be beaten, I dare say. But I could introduce myself in several ways. What if I said my name was Oswald Bastable—Airshipman.”

“You fly balloons?”

“I have flown airships, sir. Ships twelve-hundred feet long which travel at speeds in excess of one hundred miles an hour! You see. I am mad.”

“Well, I would say you were inventive, if nothing else. Where did you fly the airships?”

“Oh, most parts of the world.”

“I must be completely out of touch. I knew I was receiving the news rather late, but I’m afraid I haven’t heard of these ships. When did you make the flight?”