Jerusalem Commands

Michael Moorcock

MICHAEL MOORCOCK

Winner of the Nebula and World Fantasy awards

August Derleth Fantasy Award

British Fantasy Award

Guardian Fiction Prize

Prix Utopiales

Bram Stoker Award

John W. Campbell Award

SFWA Grand Master

Member, Science Fiction and Fantasy Hall of Fame

Praise for Michael Moorcock and Jerusalem Commands

‘New adventures both picaresque and grotesque take [Pyat] across bootlegging America, like a hobo, to Hollywood as actor, writer and set-designer; to Egypt with various film-making eccentrics, only to end up enacting scenes of lurid degradation for a powerful pervert…. Such escapades are Hollywood and schoolboy fantasy seen through the eyes of a talented inventor who is also a bigoted racist, egoist and abuser of women…. Moorcock shows us through this remarkable but odious bore that fascistic attitudes are not as far removed from some forms of popular fiction and fantasy as we might prefer to think.’

—Robert O’Brien, Time Out London

‘Few novelists have risen above the orthodox categories of fiction … to produce something as expansive and elaborate as this.’

—Peter Ackroyd, Sunday Times (UK)

‘The Pyat books are in some ways the most ambitious work of Mr Moorcock’s long career, and offer peculiar rewards, in that the narrator, although charming in a roguish way, is also a deeply flawed creation, and spending psychic time with the character is emotionally trying. I’m always up for a challenge, though.’

—Mike Whybark, Whybark.com

‘Moorcock’s powers of description—especially when focused on the sights and smells of megalopolis—and his range of references are immense…. Like Thomas Pynchon he can be … highly impressive…. His main achievement in this tetralogy … is to force the reader to afford the luckiest bastard in the whole damn universe [Colonel Pyat] a grudging respect. Even a little affection too.’

—Mark Sanderson, Times Literary Supplement

‘Pyat is the most unreliable narrator in the fiction of the last half-century; the dustbin of history on legs. A racist, a bigot, a fanatical Slav nationalist forever ranting of the glories of Byzantium and its need for ever-ceasing vigilance against the malign forces of Carthage (by which he means Jews, Muslims and all of Africa), a pedophile, a cocaine addict, a man for whom the distinction between lying and self-delusion has long since eroded, an eternal betrayer forever feeling himself perpetually betrayed by others…. Pyat is so consistent, so much of a piece, so relentless in his repulsiveness that the reader ends up reluctantly saluting his indefatigability, as well as that of Mr Moorcock, his editor and Boswell.’

—Charles Shaar Murray, The Independent (UK)

‘Through Moorcock I was introduced to a whole set of countercultural possibilities, as well as to the idea that writing didn’t have to conform to—well, to anything really.

After the manic productivity of the 60s and 70s, Moorcock slowed down (slightly) during the 80s and 90s, producing increasingly literary and complex picaresques, such as the tetralogy featuring Captain Pyat, an anti-hero whose peregrinations through the 20th century take him from the Russian revolution to a flat on the Portobello Road, where he tells his unlikely tale to a writer called Moorcock. However, despite productions like the Pyat books, which are maximalist fables of the type that have made global stars out of Pynchon or Rushdie, Moorcock has never shown any interest in eschewing genre.’

—Hari Kunzru, The Guardian (UK)

Jerusalem Commands

Michael Moorcock

© 2013 by Michael Moorcock

This edition © 2013 PM Press

Introduction © 2013 by Alan Wall

ISBN: 978–1-60486–493–9

Library of Congress Control Number: 2012913633

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be transmitted by any means without permission in writing from the publisher.

Bibliography reprinted with the kind permission of Moorcock’s Miscellany (www.multiverse.org)

Project editor: Allan Kausch

Copy editor: Gregory Nipper

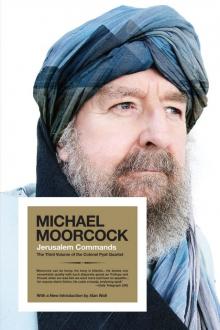

Cover by John Yates/www.stealworks.com

Interior design by briandesign

Copyright © Michael Moorcock 1992

Cover photo by Linda Steele

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

PM Press

P.O. Box 23912

Oakland, CA 94623

PMPress.org

Printed in the USA on recycled paper, by the Employee Owners of Thomson-Shore in Dexter, Michigan.

www.thomsonshore.com

To the memory of Arnold Schoenberg who, on July 30, 1933, ten days after the formal signing of the Concordat between Hitler and Pope Pius XI, reconverted to the Jewish faith.

FOR ANDREA DWORKIN

Contents

INTRODUCTION BY ALAN WALL

INTRODUCTION BY MICHAEL MOORCOCK

Jerusalem Commands

APPENDIX

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Introduction to Jerusalem Commands

In the editorial introduction which Michael Moorcock provides to this third instalment of the memoirs of Maxim Arturovitch Pyatnitski, aka Colonel Pyat, we are told that the old rogue’s philosophy is as follows: ‘Constant change is the paramount rule of the universe. To reduce the rate of entropy, we must make enormous efforts, using skill, intelligence and morality to create a little justice, a little harmony, from the stuff of Chaos.’

This is probably the only moment of intellectual congruence between the paranoid racist from Notting Hill and the eminent Austrian physicist Erwin Schrödinger, who in 1943 delivered a series of lectures at Trinity College, Dublin, in which he argued that living forms drain their surroundings of whatever order they possess in order to bring more order into their own temporary existences. This was effectively the formulation of a law of anti-entropy, and humanity was better at it than any other living organism, because we represent the most successful form of life ever known. Our civilisation is a reversal of the entropic principle, however brief; order increases here with us whereas everywhere else in the universe it is decreasing. The ultimate fate of the universe, a teleological decline into the maximum possible state of disorder or thermodynamic equilibrium, is briefly countermanded by humanity and its historic achievement.

The books that constitute the Pyat Quartet raise an interesting question: how precisely do we contribute our quotient of order in this universe of ultimate disorder by fabricating monsters? Why does Dickens make Bill Sikes, or Shakespeare create Iago, whose ‘I am not what I am’ directly contradicts the Almighty’s ‘I am that I am’ in the Book of Exodus? Pyat presents himself to us here as cosmologist and theologian, moralist and political commentator, not to mention cokehead extraordinaire. The white powder is to our grubby self-denying Jew what laudanum was to Coleridge and De Quincey: a universal panacea, altogether too expensively purchased. Even Sherlock Holmes (not to mention Freud) employed the snow and its blissful narcosis to alleviate the longueurs between cases, but he of course injected rather than snorting. Pyat, as someone remarked of a recent American president, must have had a nose like a vacuum cleaner.

He is also a great respecter of nature, whatever his clamorous caveats regarding the human variety. He has this in common with one of his heroes, Adolf Hitler, in whom vegetarianism and a devotion to the Bavarian high spots seemed to merge the noble solitaries of Caspar David Friedrich’s mountain paintings with the murderous besuited anonymity of Adolf Eichmann. Pyat laments the ceaseless trashing of our planet that modern industrial society effects. He died before he could watch so many of these nature-degrading industries dying in their turn. Th

at’s in the West, of course; it would surely not have been lost on our student of comparative civilization, that each industry lost in the Western Hemisphere represents another one gained in the east. Down goes Detroit; up comes Beijing. The industrial revolution is replaying itself through the looking glass, with equally deleterious environmental effects, this time rising with the sun.

And so Pyat once more romps on, having made an enemy of the Ku Klux Klan, he turns up in Hollywood, talking to Sam Goldwyn in Yiddish. Then we are off to North Africa where Pyat, metamorphosed into the movie star Max Peters, plays his part in creating a pornographic film. Brutish sex is to be had in the Sahara, where the clear moral to be drawn is that folks don’t necessarily improve the nearer they are to the soil, or the sand. Rousseau got that one wrong, evidently. Pyat meanwhile effectively writes his own version of The Protocols of the Elders of Zion in these pages, without restricting the worldwide conspiracy to Jews: why forget the part played in our current disasters by Communists and Muslims? One thing you can say for Pyat: his racism boasts a certain universalism. Only the Cossacks come out of it all unscathed. It is to them of course that he attributes his genetic evidence. Not that anyone else ever believes him.

So back for a moment to Schrödinger. Our order is, he insisted, a type of anti-entropy. We suck order out of our environmental surroundings, and one of the forms it then takes is art. Pyat is a pantomimic figure of prejudice, mendacity and unscrupulous appetite. He struts through his fictional life like a dictator without a specific country in which to dictate. He utters his untruths with such zeal and conviction that he undoubtedly believes them himself. Is he then a parable for our times? Is he, as Hamlet recommended to the players, holding up the mirror to nature, in this case the latest version of our human nature? Is he in fact some hideous parody of Everyman? The dramatic irony here is that we see on every page that Pyat’s call for a concerted battle against entropy is itself lethally entropic, since it is corroded from within by political and intellectual self-deception.

His loathing of all things Islamic does now seem curiously prophetic. Maybe the old boy is gazing down on us even now, searching for one last sachet of white gold, while muttering: ‘I told you so.’

Alan Wall

University of Chester

2013

Introduction

I MUST APOLOGISE to readers who did not expect to wait some eight years between the second and third volumes of Colonel Pyat’s memoirs and I hope they will forgive me when they understand the difficulties involved in preparing his papers for publication, in transcribing tape-recordings and fitting those into some sort of chronology. Meanwhile my own work had to be done, so it was not until February of 1986 that I found time to travel to Morocco and then to Egypt, taking part of Pyat’s own journey by sea and by land (being lucky enough to rediscover the now dry Zazara Oasis), ultimately to Marrakech. Here the Colonel’s account of the fabulous court of El Glaoui, Pasha of Marrakech, differs somewhat from Gavin Young’s sketch in Lords of the Atlas.

Once again, in Marrakech and the settlements of the Sub-Sahara, I was fortunate, meeting many people willing to help in my research. Several of these remembered the Colonel as ‘Max Peters’. Many older people, I discovered, revered him. They said he was the greatest Hollywood star of all. They were disgusted, they said, by the jealous rumours suggesting he was Jewish. Yet in Egypt scarcely anyone knew of him. I was lucky enough to talk to a retired English policeman in Majorca. He had been in the Egyptian Service under Russell Pasha (whose memoirs also confirm much of Pyat’s account) during the time Colonel Pyat was in that country and remembered many of the facts almost identically, especially in relation to the drug- and slave-trades. Apart from their variant points of view, the facts and names agree in important detail and further research, in The Egyptian Times and other papers of the day, make it clear that ‘al-Habashiya’ was a well-known character, controlling Cairo’s red-light district and with interests in every wicked business from Timbuktoo to Baghdad. Sir Ranalf Steeton and the other Englishmen Pyat mentions are more elusive, although Steeton undoubtedly ran some kind of film-distribution business, and, of course, we have all heard of Quelch’s brother.

My retired policeman vaguely remembered a Max Peters. When I mentioned Jacob Mix, however, he became enthusiastic. ‘The embassy chap. CIA, wasn’t it?’ He had known Mr Mix well, he said, not in Egypt but in Casablanca just at the beginning of the war, and they had kept in touch. The colonel’s old friend was now retired and living in Mexico. I was astonished at this revelation and excited, for here was someone who could, if they had wished, have told Maxim Arturovitch Pyatnitski’s story from a very different perspective.

As soon as I was back in England I wrote to Mr Mix and we corresponded. That correspondence was extremely helpful in assembling the present volume, but it was not until May 1991 that I was able to get to his part of Mexico, and make the journey to the village where Mr Mix lived ‘in heavenly exile’, just outside Chapala, on the shores of the beautiful polluted lake.

Mr Mix had retained the so-called ‘Ashanti’ good looks Pyat had described, though his beard and hair were pure white so that I was unwittingly reminded of the benign Uncle Remus in Disney’s Song of the South. Until he spoke, it was hard to believe he had been an American spy. He was courteous in a delicate, old-fashioned way, typical of Southerners of his generation, and his quiet irony was also familiar. In spite of his advanced years, he was relatively fit. Certainly he was happy to talk as much as he could about his time with Colonel Pyatnitski, of whom, he said, he had fond memories.

Mr Mix admitted that Pyatnitski often made Adolf Hitler seem like Mother Theresa but said he had remained fascinated by him partly because of the contradictions, but the main reason for his staying with the Colonel was, he said, entirely self-interested. ‘The man was plain lucky,’ said Jacob Mix, laughing. ‘I held tight to him the way you hold on to a rabbit’s foot.’ He confirmed that the Colonel had, indeed, won fame as a film-star in B-Westerns and serial ‘programmers’ for several shoe-string independent producers of ‘Gower Gulch’ (the Hollywood location of most such operations) and showed me a box-office placard in full colour, with vivid reds and yellows, solid blacks. It was for a film called Buckaroo’s Code and showed a mounted cowboy, a bandanna veiling the lower half of his face, waving out at the audience. The film starred Ace Peters and was from a studio called DeLuxe. It was clearly from the period of the mid-1920s. Sol Lessor, whom I knew in the late 50s, mentioned his involvement with a fly-by-night outfit making dozens of cheap Westerns and adventure movies for theatres that needed to show at least two features, a serial, a cartoon and a newsreel to remain competitive. Mr Mix also let me see a cigarette card issued in England by Wills and Co.—a cowboy in a tall white Stetson, with a dark bandanna hiding his nose, mouth and chin, with the caption Ace Peters as THE FLYIN’ BUCKAROO (DeLuxe). There had been other memorabilia, said Mr Mix, but most of it had been lost when, shortly after his retirement, his flat in Rome was set on fire.

I had never thought I would associate Colonel Pyat with one of my childhood heroes. Many boys who grew up in postwar Britain read the exploits of The Masked Buckaroo in the weekly and monthly ‘penny dreadfuls’ of the day. Although he originated in America, he survived longer in Britain. Like Buck Jones, The Masked Buckaroo was a potent folk-hero. Jones had been forgotten in America after his death in the famous Coconut Grove fire in 1944, but survived in the UK with his own magazine until about 1960. The Masked Buckaroo magazine itself folded in 1940 due to a shortage of news-print. Colonel Pyat had a few tattered copies from the 20s and 30s and they are seen rarely, even in specialist catalogues. My own collection was inherited from my uncle, a great Western enthusiast.

I mentioned to Jacob Mix that in his fashion Colonel Pyat had spoken highly of him. This made the old Intelligence agent laugh heartily. He remembered Max’s praise, he said. He was as helpful as he could be and some of his detailed information was invaluable in making sense of parts

of Pyat’s manuscript. Sadly, Mr Mix died very soon after we had enjoyed his company and hospitality and is now buried in the ‘Protestant Cemetery’ near Chapala.

With no experience of formal religion I found the colonel’s views often baffling and frequently primitive. He argued that any social stability we had was due to our efforts to make the best of God’s gifts. We were duty bound to maintain and extend that stability. For me Pyat’s argument, that entropy is the natural condition of the firmament and that the physical universe, being in a perpetual state of flux, was not an environment friendly to sentient life, though couched in modern scientific terms, had a somewhat mediaeval ring. ‘Constant change is the paramount rule of the universe,’ he claimed. ‘To reduce the rate of entropy, we must make enormous efforts, using skill, intelligence and morality to create a little justice, a little harmony, from the stuff of Chaos.’ His flying cities represented a kind of clearing in the universal turmoil. He valued the ideals and institutions of democracy, he said, ‘as embodied in the pre-war United States’. The only cause to which he subscribed at his death was, I discovered, Greenpeace. ‘I shared my love of nature with all the real Nazi leaders,’ he told me. ‘We were great conservationists long before it became fashionable.’ He claimed he himself had played an important part in a successful recycling scheme in Germany but when I asked him for details he became oddly elusive and changed the subject entirely, asking me if I knew the German rhyme from The Juniper Tree by Grimm.

This was a typical strategy of his, veering off into an exotic literary byway or contentious political track so that anyone who had come too close to some truth he was in danger of recognising in himself would be carried into fascinating excursions or bound from conscience to respond to some of his more reactionary outbursts. It could also have been that I was not always sensitive to every associative leap he made—from recycling to Grimm, for instance—and it is when I have doubts of this kind that I wonder if I am perhaps the best editor for these memoirs. At such times I am seriously tempted to abandon the whole thing—lock, stock, barrel, papers, tapes, notes, scrapbooks and all the half-festering, crumbling, encrusted bits and pieces of that old man’s extraordinary life, most of which dates from before he was forty. After he settled in England he had few very dramatic adventures.