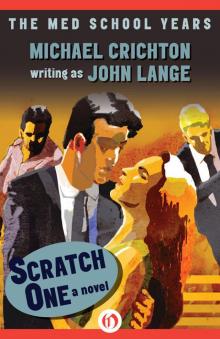

Scratch One

Michael Crichton

Scratch One

A Novel

Michael Crichton writing as John Lange

Contents

Chapter I

Chapter II

Chapter III

Chapter IV

Chapter V

Chapter VI

Chapter VII

Chapter VIII

Chapter IX

Chapter X

Chapter XI

Chapter XII

Chapter XIII

Chapter XIV

Chapter XV

Chapter XVI

Chapter XVII

Chapter XVIII

Chapter XIX

Chapter XX

Chapter XXI

Chapter XXII

Chapter XXIII

Chapter XXIV

Chapter XXV

A Biography of Michael Crichton

Chapter I

Monday: Principalité de Monaco

VICTOR JENNING, TANNED AND very fit, walked down the steps of the Casino into the cool night air. They were already bringing his blood-red Lamborghini around from the lot. It was a new car, and Jenning was pleased with it—Carrozzeria Touring body mounted over a 3.5 liter V-12 engine that ran smoothly at 240 kilometers an hour. It was a hardtop, of course. Jenning loathed driving fast in an open car—unless he was racing—and he had rolled enough cars to have a healthy respect for solid protection overhead.

People were gathering to admire the car as he came to the bottom of the steps. It was only natural; the car had never been produced prior to 1965, when old Ferrucio Lamborghini, the tractor and oil burner tycoon, had established a limited production shop in Cento, just a few miles from Ferrari’s plant at Maranello. Three hundred Lamborghinis were made a year, so it was still quite a rarity. It had cost him $14,000.

As he made his way around the crowd, he answered their questions with smiles and a slightly bored voice, then got in behind the wheel. He was a jaded man, and so felt only mild pride, but it was sufficient to make him forget—momentarily at least—the ten thousand dollars he had just dropped that night at baccarat, in a particularly poor run of luck.

He started the engine, listening with satisfaction to the bass growl from the twin exhausts. The crowd parted, and he reached down for the lights. His hand flicked on the windshield wipers, and he had a twinge of embarrassment. Damn! It was painfully obvious that he’d owned the car just a week. He bent over to peer at the switches.

At that moment his windshield shattered in front of him.

The crowd gasped; somebody screamed. Another shot, and Jenning, who had immediately dropped as low as he could, felt pain in his right shoulder. He turned on the lights, released the brake, and put the car quickly into reverse. Still hunched over, he roared backward, sat up, spun the wheel around, and tore off into the night. Air blew through the gaping hole in his windshield, and he swore to himself.

Victor Jenning was a man accustomed to attempts on his life. There had been four in the last two years. None had come close to succeeding, though he had a slight limp as a result of the second. In a strange way, he did not mind the assassination attempts—they were part of the game, one of the risks in his line of work. But he hated to see his new car damaged. It would take weeks, now, to get a new windshield fitted properly.

As he drove through the dark streets of Monaco toward the doctor, he was so furious that he did not bother to reflect that, had he known how to work his lights, he would probably be dead.

Tuesday: Cairo, Egypt

One of the Arabs held a gun. “It will not be long now,” he said pleasantly.

In the back seat of the taxi, the European stared at the gun, at the Egyptian holding it, and at the back of the neck of the driver. They sped through the dark streets of the city.

“Where are you taking me?” he said. He was French, and spoke Arabic with a slurred accent.

“To a meeting. Your presence is desired.”

“Then why the gun?”

“To assure … punctuality.”

The Frenchman sat back and lit a cigarette. He remained cool; it was part of his training. He had been in tight situations before, and he had always managed to escape safely.

The car left the city and headed south, into the desert. It was a moonless May night, black and cool. The French man could see the outlines of the palm trees that lined the road.

“Who is this person I am meeting?”

The Arab laughed softly: “You know him.”

They drove for ten minutes, and then the Arab with the gun said, “Here.”

The driver pulled off the road, onto the sand. The Nile was a few hundred yards away.

The car stopped. “Out,” the Arab said, motioning with the gun.

The Frenchman got out and looked around. “I don’t see anybody.”

“Have patience. He will be here soon.” The Arab drew a pair of handcuffs from his pocket and handed them to the driver. To the Frenchman, he said, “If you please. Our man is rather nervous. This will reassure him.”

“I don’t think—”

The Arab shook his head. “No arguments, please.”

The Frenchman hesitated, then turned and held his hands behind his back. The driver clicked the handcuffs shut.

“Good,” said the Arab with the gun. “Now we will go to the river, and wait.”

They walked silently across the sand. No one spoke. The Frenchman was worried, now. He had made a mistake, he was sure of it.

It happened with lightning swiftness.

One of the Arabs tripped him, and he pitched forward on his face into the sand. Strong hands gripped his neck, forced his head down. He felt the grainy sand on his lips, in his eyes and nose. He struggled and kicked, but the Arabs held him firmly. His mind began to reel, and then blackness seeped over him.

The Arabs stepped back.

“Stupid fool,” one said.

The driver removed the handcuffs. Each man took one leg, and they dragged the body to the river. The Arab put his gun away and held the body underwater with his foot until it sank. It would rise to the surface later, when it was bloated and decomposing. But that would not be for several days.

The body sank. A few final bubbles broke the calm water, and then, nothing.

Friday: Estoril, Portugal

The man walked across the rocks in his bare feet, looking into the setting sun. The waves of the Atlantic crashed into the rock. He was an American, a minor consular official attached to the office in Barcelona. He had received news of his transfer to Nice just three days before, and had decided to relax for a few days before moving. He was accustomed to traveling, and did it easily, so there were no major preparations to look after. Lisbon had been the perfect choice for a short break. He had been here during the war, and loved it deeply. Particularly this stretch of coast, west of the city, past the point where the Tagus River emptied into the ocean.

He smiled, breathed deeply, and reached in his pocket for cigarettes. To his right, the rocky shelf leading up from the sea ended in a sloping pine grove; to the left, the water rushed up against sharp, eroded stone. He was alone—few people came here at evening, this early in the season. He felt relaxed and cleansed after the bustle of Barcelona. The match flared in his hand, and he touched it to the cigarette. What the hell was he going to do in France, where cigarettes were so expensive?

Offshore, a fishing boat started its motor, and he listened to its faint puttering as it pulled away. He would have lobster tonight, he decided, in a little place in Cascais. Then he would return to his hotel and compose a letter to his girl in Barcelona, explaining that he had been sent away, suddenly, and was returning to the United States. The Spaniards were accustomed to hush-hush, sudden maneuverings among any kind of government officials; Mari

a would take it well. And although he would miss her, he was confident he could find a suitable replacement on the Riveria. Hell, if you couldn’t find a girl there, you couldn’t find one anywhere.

Behind him, there was a sharp crack! It was a sound he did not hear, for by that time, the bullet had entered the back of his head, smashing the occipital bone and burying itself deep in his cerebellum. He felt a momentary twinge of pain, and was pitched forward onto the rocks. His face smashed down hard, breaking the bones of his nose and jaw. Blood flowed out.

Two other men, neatly dressed in sport clothes, viewed the fallen body with satisfaction. The tide was coming in; within an hour, these rocks would be submerged, and the body carried out to sea. It was a good, clean, neat job. They were pleased.

Chapter II

Saturday: Köbenhavn, Denmark

PER BJORNSTRAND, A NORWEGIAN, checked into the Royal Hotel at 4:00 p.m., and went immediately to his room to shower and change. He had just arrived at Kastrup Lafthavn on a direct flight from Oslo, and it had been a tiring trip—the plane was delayed in Oslo, and there had been considerable turbulence for over an hour in the air.

He felt better after cleaning up, and went down to the sleekly modern lobby. He dropped into one of Arne Jacobsen’s egg chairs, and ordered a martini. They were a bad habit, martinis, which he had picked up from his British business associates, and they, no doubt, from the Americans. So many of the world’s habits were American, these days. He lit a Lucky Strike filter cigarette and looked across the room at the slim blonde behind the reception desk. She was a rather elegant creature, with hair upswept, and high cheekbones.

Whenever Per Bjornstrand came to Copenhagen—which was often, since his business demanded it—he stayed at the Royal. He could, of course, stay with his sister-in-law in Hilleröd, but he always told himself that this was too far from the center of town. The truth was that he loathed his sister-in-law, a mindless child-bearing creature. And besides, the Copenhagen girls were too much to pass up.

He sat back in the chair, which encircled him like a womb, and puffed on his cigarette as he ran over his schedule for the next two days. Tomorrow he would be relatively free and would have lunch with Jörgen, an old friend from the war. On Monday morning he must see the shipping agents and arrange for transfer of the consignment from Copenhagen to Marseilles, and for storage there. He should, of course, spend Monday afternoon shopping for anniversary presents for his wife; the smart shops along Amagertorv would be filled with things she’d adore. But it was still cold; outside, along Hammerichsgade, the wind whistled bleakly, pounding rain against the glass walls of the lobby, and he couldn’t imagine he’d feel much like shopping, even by Monday.

His thoughts were interrupted by the arrival of a new girl, dark and long-limbed, dressed in a tightly belted trench coat which emphasized her fine legs and narrow waist. She had very blue eyes, and a wide smile which she lavished upon Bjornstrand as she passed. He smiled back, let his eyes flick quickly over her body, and observed that she was alone. That was significant. He would ask at the desk about her later, and phone up to suggest she join him for a drink. There was no sense being alone on a cold, rainy evening. After all, he thought, breathing deeply to expand his chest, he was only forty-five, still virile and still handsome. It wouldn’t last forever.

His mind, reluctantly, returned to business. He was a dealer in armaments, and—in a small way—a manufacturer. He now had a surplus of automatic rifles and assorted small arms which the Norwegian Army was selling as it upgraded its own issue, and a buyer in southern France had contacted him. The shipment was required quickly, so Bjornstrand had come to Copenhagen to manage the details himself. It was a lucrative business, and very enjoyable.

The waiter came with a small bowl of hors d’oeuvres, and the martini. “Your check, please.”

He signed, adding the tip. “And your room number?”

He scrawled it, and returned the slip. The waiter left him, and Per Bjornstrand picked up the martini. The outside of the glass was suitably frosted. He took a tentative sip. Very dry, pleasantly cold—the liquid ran down his throat, and caught fire in his stomach. But it was also bitter, strangely bitter.

For a moment, he wondered why. Then a giant hand gripped his innards, choking him. Per Bjornstrand coughed once, and made gurgling sounds as he fell back in his chair and died.

Saturday: Paris, France

Inspector Edgar Duvernet followed the doctor down the aseptic white corridor. Duvernet was a short man, and he resented the doctor’s long, easy strides; it was unbecoming for a member of the police force to puff along at a taller man’s heels. They came to the door.

“I warn you, he does not look pretty,” the doctor said. Duvernet thought he caught a hint of condescension, an anticipation that he, Duvernet, could not take what was coming.

He snorted. The doctor opened the door. The patient was alone, on his back in bed. One arm was extended, strapped to a board; a bottle of liquid was dripping into the hand, through a needle inserted in a vein. The hand was swollen, the veins bulging. For a moment, this was all Duvernet could see, and he did not find it alarming. He stepped closer.

Then he saw the face. It was covered with a plaster guard, to protect it, but much of the flesh of cheeks and jaw were visible. It was horrible, and despite himself, Duvernet gasped. The skin had the color and texture of a half-deflated football. The purple-black eyes were puffed shut, and a neat suture ran across the nose, then around one eye, terminating in a straight line down the cheek.

“You should have seen him before,” the doctor said. “Bad?” Duvernet asked, still looking at the patient. He did not trust himself to face the doctor, just yet. Mon Dieu, it was stuffy in here! He was feeling suddenly nauseous.

“The whole right side of his face was caved in, and his right eye nearly scooped out of the socket. It was an inch lower than his left, when we got him. His jaw was broken and his nose crushed, his upper lip torn badly in two places, several teeth gone. We had to—”

Duvernet wobbled, and tottered over to a chair. The doctor quickly opened a window, and passed smelling salts under the policeman’s nose. New to the job, he thought. “I don’t mean to bore you with technical details,” he said.

“Not at all,” Duvernet said, jerking his head up from the ammonia odor and looking quickly at the doctor, searching for signs of amusement. He was relieved to find none. It’s because I am new to my job, Duvernet thought; only that. In a month or two, such things will not bother me. “Is he all right?” Duvernet asked, looking at the floor. “He’ll survive, though he’s lost a lot of blood. We’re trying to see that he doesn’t develop meningitis, that’s the big worry.” When the man broke his nose, he had shattered his ethmoids, exposing the dura mater covering the brain. It made things very touch and go, the doctor knew, particularly when resistance was severely lowered. He frowned. “Any idea how it happened?”

Duvernet shook his head. “None at all. We were hoping he might be able to tell us.”

“Not for weeks, I’m afraid. He’ll be under heavy sedation for some time, and his jaw is wired shut. Do you have everything you need?”

“Yes. Just tell me: where is the nearest telephone?”

“At the end of the hall. In an emergency, the desk will give you an outside line.”

“Bon. Merci.” Duvernet stood, shook the doctor’s hand, and sat down again, very shaky. He looked for a long time at the patient’s feet, and then at the bottle of fluid, with the tube going down to the hand. He breathed deeply, and shortly began to recover.

This man was Jean Paul Revel, an exporter from Marseilles. Perfectly straightforward and honest. He had come to Paris on business—his wife had verified that, in a telephone call—and had arrived on the 7:14 train at the Gare d’Orleans. He had left the station, and entered the Metro station, carrying a small suitcase. Somehow, M. Revel fell forward from the platform into the path of an onrushing train. Observers stated that he flailed his arms to regain his bal

ance, and some quick-witted person grabbed his coattails. Probably he would have escaped injury entirely, had not the train come along at that moment and smashed into his face and chest. He suffered a broken collarbone, two cracked ribs, and a badly battered face which had been immediately operated on.

The police were interested in questioning him, and normally would have been content to wait until he had recovered. There was, after all, no indication of foul play. But the call from the Deuxième had been put through that morning, and so here he was, Edgar Duvernet, on the job.

He reached into his pocket and withdrew his pistol. He flicked off the safety and placed it carefully in his lap. He had five hours before the second shift went on. Duvernet looked around the room, hoping for something to read, seeing nothing. Outside, it was raining, the chilly drops falling slantwise against the window, streaking the view of the newly green trees.

Saturday: Nice, France

Dr. Georges Liseau, looking slim and elegant, strode into the room. The five men collectively known as the Associates stood as he entered. Like himself, many had the swarthy complexions which betrayed an Algerian birth; one or two had knife scars on their faces, but otherwise they were unexceptional, respectable-looking. One would never suspect that they were all Arab agents.

“Sit down, gentlemen. This isn’t a board meeting.” Dr. Liseau’s voice was mildly sarcastic. As usual, he took his seat at the head of the table, and did not remove his sunglasses. He surveyed the men in the room, then said, “Any explanations?”

There was a general rustling of paper and shifting of position, but no one spoke.

Liseau sighed. “Our record,” he said, “is not very good. The Jenning business was executed quite badly. The attempt in Paris was amateurish. I understand the man is alive, and expected to recover with nothing more than a few scars on his face. The arms shipment may not be delayed. We shall have to improve our efficiency.”